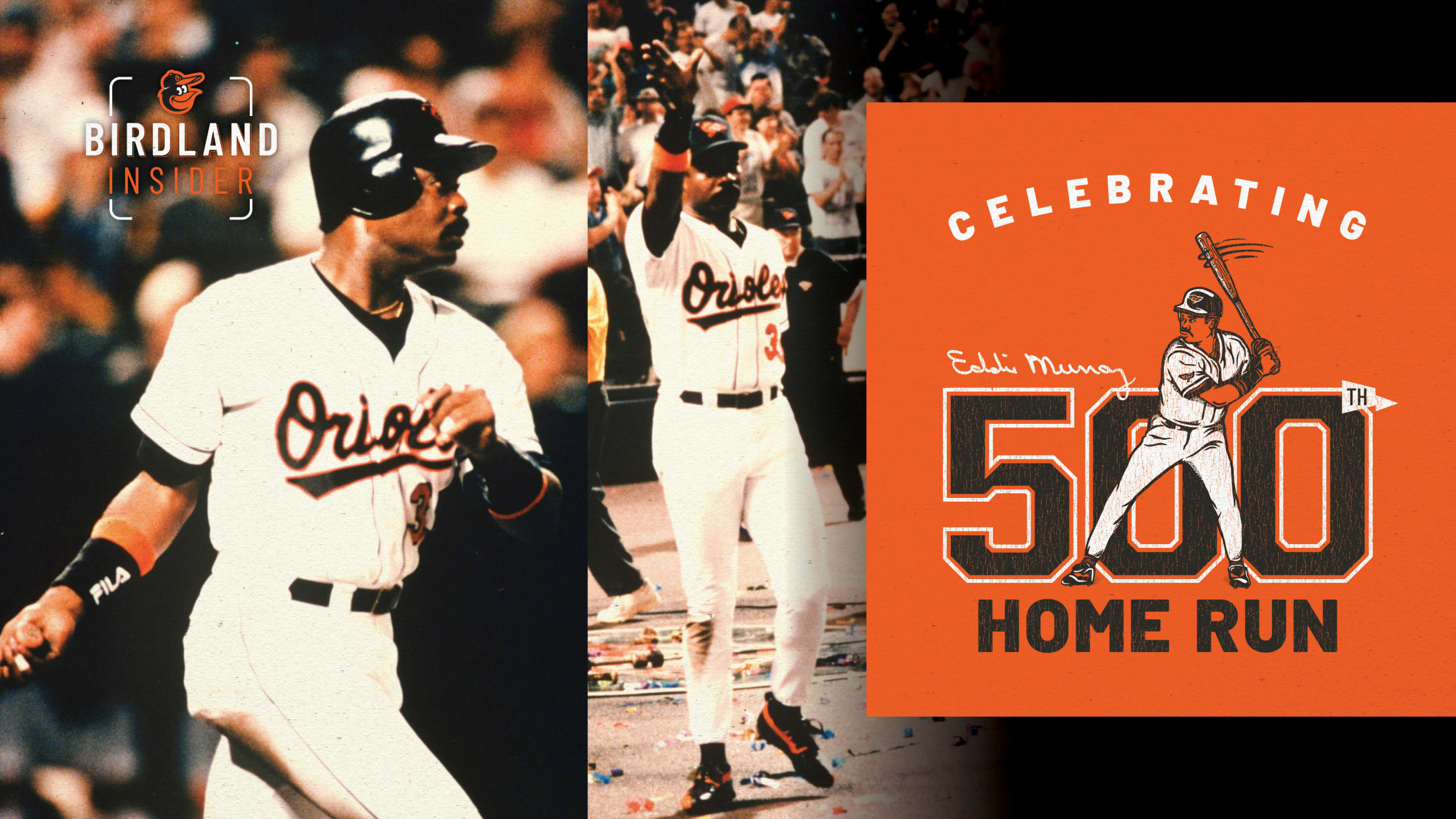

Celebrating Eddie Murray’s 500th Home Run

The clock was bearing down on midnight, but Eddie Murray wasn’t thinking about the promise he’d made eight hours earlier. After a rain-delayed start of nearly 2 ½ hours, the Orioles trailed the Tigers, 3-2, in the bottom of the 7th inning at Camden Yards. There was a game on the line. That’s all Murray thought about.

He had forgotten that he had earlier told teammate Cal Ripken Jr., “Today’s the day.”

He had forgotten his reaction upon learning that the date – September 6, 1996 – was one year to the day of Ripken’s passing Lou Gehrig’s immortal record by playing in his 2,131st consecutive game.

But after Ripken bounced out to start the bottom of the 7th inning, Murray swung at Felipe Lira’s first pitch and sent it rocketing into the seats in right center field. It was the 500th home run of a glorious 21-year career, the first 12 of which had been spent with the Orioles before a bittersweet trade and much-loved reuniting that July. He had been away 6 ½ years, but it was like he never left.

With that mighty left-handed swing, the Camden Yards crowd of 46,708 – contracted somewhat by the rain as the game steamed from Friday night toward Saturday morning – cheered lustily, just like the old days at Memorial Stadium.

“Ed-die! Ed-die! Ed-die, Ed-die!,” they chanted as confetti rained down from the upper reaches of the ballpark.

As Murray circled the bases in his typical stoic manner before crossing home plate and being mobbed by his teammates, he could have made mental notes of what brought him to this moment in baseball history, and a particular irony.

*****

With the historic home run, Murray became only the third player in baseball history to record 3,000 hits and 500 homers, joining Hank Aaron and Willie May. Since then, three other players have joined the 3,000/500 club – Rafael Palmeiro, Alex Rodriguez, and Albert Pujols (with Miguel Cabrera closing in on 3,000 hits).

He had been the most consistent player of his era from his rookie season with the Orioles in 1977 until his trade to the Dodgers after the 1988 season – so consistent that he earned the nickname “Steady Eddie.” It seemed to go with the necklace he often wore, which read, “Just Regular.”

In those first 12 seasons with the Orioles, he had hit 333 home runs – most in club history before Ripken passed him less than eight weeks before Murray rejoined the club on July 21, 1996. Murray would hit 10 more with the Orioles in ’96 (the 500th homer was his ninth that season), leaving him second to Ripken’s 431 homers at 343.

In between his Orioles stints, he had played for the Dodgers, Mets, and Indians. It was with Cleveland, on June 30, 1995, that Murray had become the 20th player in baseball history to record 3,000 hits, and only the second switch-hitter after Pete Rose.

Not bad for a player drafted as a right-handed hitter – one who didn’t start switch-hitting until his third professional season, only then as a way to help him out of a Minor League slump.

Yet here he was, circling the bases after hitting his 500th career home run, as a left-handed batter.

*****

Murray was a 17-year old, right-handed hitting first baseman when the Orioles made him their third-round pick in the 1973 amateur draft out of Los Angeles’ Locke High School, where he was a teammate of future Cardinals’ Hall of Fame shortstop Ozzie Smith.

He won the Appalachian League MVP his first pro season, batting .287 with 11 home runs and 32 RBI in 32 games for the Orioles’ Bluefield affiliate. The next year with Miami, he was named to the Florida State League All-Star team, batting .289 with 12 homers and a league-leading 29 doubles before an end-of-season call-up to Double-A Asheville.

After Murray struggled for several months at Asheville in 1975, manager Jimmie Schaffer had the then-19-year-old come out for early batting practice and suggested he take a few swings left-handed. It was a tactic Schaffer had used on other slumping players as a way to get them to feel more comfortable when they returned to their natural side of the plate.

"So I asked Eddie to try it, and he just smiled a bit," Schaffer told the Baltimore Sun in 2003. "He started hitting line drives all over the ballpark. In fact, he hit a couple in the seats…It was just him and I. I never told anyone in Baltimore.”

Murray continued to hit left-handed in batting practice for several weeks before trying it in a game late in the season. He singled in his first lefty at-bat, and Schaffer told his bosses in Baltimore. Though reluctant at first, the Oriole brass sent Murray to the Fall Instructional League to work on switch-hitting.

In 1976, Murray returned to Schaffer and Double-A ball – the Orioles had moved their affiliate to Charlotte that year – and by mid-season he had hit 12 homers: six batting right-handed, six batting left-handed. He was promoted to Triple-A Rochester and between the two clubs, batted .289 with 23 homers and 86 RBI.

In 1977, he kept on the big league roster at the insistence of Orioles manager Earl Weaver after a strong spring. Murray won the American League’s Rookie of the Year award. The rest, as they say, is history.

He never won a Most Valuable Player award but finished in the top five on six occasions, including a pair of runner-up finishes in 1982 (to Milwaukee’s Robin Yount) and 1983 (to teammate Ripken).

He led the league in home runs and RBI only once each – both in the strike-shortened 1981 season – but in his first 20 seasons, hit at least 20 homers 17 times and drove in at least 76 runs each year.

He also homered from both sides of the plate in the same game a Major League-record 11 times in his 21-year career.

*****

Murray had hit eight homers since rejoining the Orioles in the July trade with Cleveland that sent pitcher Kent Mercker to the Indians. His bat helped prop up the Orioles lineup, and the team was now in the thick of the first wild card race in AL history. He hit career homer number 499 on August 30 at Seattle, then went homerless in the last five games of the Orioles’ West Coast road trip before the team returned to open a seven-game homestand on September 6.

“I remember that day very well,” Murray said last year on the Orioles Magic podcast. “I came into the ballpark and I end up saying (to Cal Ripken), ‘Rip, today’s the day.’ I said, ‘I’m going deep today.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.’

“So, we go out to run sprints just before we start the game. We run the first one, me and him run together. We come back and as we start to run the second one, they put up that this was the day he (broke Gehrig’s record) and I’m going, ‘No!’ And he goes, ‘Yeah, you already said it, you gotta do it today.’”

The Orioles had prepared for the moment, handing out orange placards to fans with “Ed-die!” on them. It looked for a while as if they’d have to print more for the next night as rain pelted the ballpark. The game did not begin until 9:57 p.m. Murray walked and grounded out in his first two plate appearances.

“I came home off the road trip and started to struggle a little bit because all of a sudden, I saw a sea of orange,” Murray said. “And I jumped out of the box and everybody’s holding up these signs with my name on them. And I’m going, ‘Oh, no, they think I can do this on call.’”

By his third at-bat, he was a bit more accustomed. It was also getting late. Facing Lira for the third time in the game, Murray turned on the right-handers first offering, a fastball, and sent it seven rows up the bleacher seats to the left of the right field scoreboard. It was 11:48 p.m. on September 6.

As the confetti rained down, a banner unfurled on the batter’s eye wall in center field: “Congratulations Eddie 500.” Murray was coaxed out of the dugout by the fans three times, waving and acknowledging their cheers for more than eight minutes before the game resumed.

“I got it in under the 12 o’clock hour, which counted for that day I was gonna hit it,” Murray said. “But you know, that was a really, really good time to come back and get that out of the way.”

The home run tied the score, 3-3. The Orioles eventually lost, 5-4, in 12 innings. The bars were closed by the time the game ended at 2:15 a.m.

*****

Murray would go on to help the Orioles to the playoffs before becoming a free agent and finishing his career in 1997 with the Angels and Dodgers. He ranks 27th in baseball history with 504 home runs, 14th in hits (3,255), and 11th in RBI (1,917). Among switch-hitters, he is second, second, and first.

He also played more games and had more assists at first base than anyone in history. His 128 sacrifice flies are more than anyone in history. He hit .399 with the bases loaded, including 19 grand slams, fourth in baseball history. Murray was an eight-time All-Star and a three-time Gold Glove winner.

He was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame on his first ballot in 2003.

Murray was voted Most Valuable Oriole a club-record seven times, and his uniform number 33 is one of six worn by former Orioles to be retired by the club. Along with the other five, he was honored with the unveiling of a larger-than-life size bronze sculpture in Legends Park beyond the left field bullpens in 2012.

To honor his 500th homer off Lira, the Orioles installed an orange seat amid the sea of green in the right field bleachers where the ball landed – Section 96, Row 7, Seat 23.

After his playing days, Murray spent four seasons as a coach for the Orioles, two as bench coach and two as first base coach, and also coached several years with the Indians and Dodgers. In 2018, Murray returned to the Orioles organization, where he serves as a special advisor and community ambassador.

He continues to support the Carrie Murray Outdoor Recreational Campus in Baltimore’s Leakin Park, a camping and personal challenge program which he began funding in 1985, and also has been involved with programming for the American Red Cross, the United Way, United Cerebral Palsy, and the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation.

On Monday, September 6, the first 15,000 fans age 15 and over attending the Orioles’ 1:05 p.m. game against the Royals will receive an Eddie Murray 500th Anniversary T-shirt, commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Hall of Famer’s career.