An oral history of a record that may never be broken

On Sept. 6, 1995, Cal Ripken Jr. played his 2,131st consecutive game, breaking Lou Gehrig’s "unbreakable" 56-year-old record to become baseball’s new Iron Man. The Orioles’ 4-2 win over the Angels that night was a generational event, a celebration of one of its most beloved figures. Ripken’s streak has been credited with helping heal America’s national pastime after the strike-shortened 1994 season. The record-breaking game remains high on the short list of the sport’s most memorable.

In honor of the anniversary of that historic night, here is a retelling from the people who were there.

The Build Up

Cal Ripken Jr.: I always thought my job as a player was to come to the ballpark and play.

Billy Ripken, brother, teammate, infielder: He always had a drive to play longer and be better than the people he was around. I remember playing pickup basketball in the driveway, and he would get annoyed if we wanted to stop. My feet hurt? I’m gone. I want a peanut butter jelly sandwich? I’m in the house. He would get annoyed with that and want to play.

Phil Regan, Orioles manager: I heard so many stories about how he sprained his ankle, spent his night in the hospital and said, “I can do it.” I don’t think a stubbed toe or stubbed finger would’ve kept him out of those games.

Billy Ripken: I never quite understood how he didn’t understand my point of view, but I didn’t understand his. He always had a desire to just play. There never seemed to be enough.

Bobby Bonilla, Orioles outfielder: Gehrig’s (record) was deemed untouchable. I never even thought about it until Cal started approaching it. It was like, “Wow, that is a really big number.”

Rafael Palmeiro, Orioles first baseman: It’s just a record that no one thought would ever be broken.

Peter Schmuck, Baltimore Sun columnist: That night he broke the record was unusual in one very obvious way: that we knew it was coming for five or six years. So, it was like the slowest record ever. But he’s marching toward this record, and there is some doubt about whether it’s going to be broken. He could get hurt at any time.

Richie Bancells, Orioles head athletic trainer: His first day in Bluefield, W.Va., (home of the O’s Rookie-level affiliate) in 1978 was my first day, too. We came up together, and we developed a friendship.

Ripken Jr.: The knee injury I suffered in the (1993) brawl (with the Mariners) was probably the closest I ever came to (ending) it. I also blew out my ankle in 1985. But I played basketball in my late teens and had a number of twists, so I could deal with that sort of pain. It impaired my mobility, but I convinced myself I could contribute and play at 80%.

Bancells: People thought there was something miraculous about him achieving this. They’d ask me: Is he on a special diet? Does he do special workouts?

Regan: Leading up to it, there were a few times we had a big lead and I’d ask if he wanted a couple innings off. He wouldn’t take any. I asked him numerous times.

Palmeiro: There were days where he walked into the ballpark, especially when he was getting close to breaking the record, where I thought there's no way he's gonna play. And he always found a way.

Bancells: The truth is there were no special things, and I had a hard time convincing people of that. He never drank anything from a blender or took any secret pills or powders. He’s basically a steak-and-potatoes guy.

Ripken Jr.: There were some intense moments where it felt like I was being criticized for wanting to play. That was weird to me. I endured the criticism. I thought the best protection against that was to get out of your slump. As soon as you got out of your slump, that all went away. And the answer for my slump wasn’t in taking a mental break -- it was figuring it out on the field.

There were some intense moments where it felt like I was being criticized for wanting to play. That was weird to me.

Cal Ripken Jr.

Billy Ripken: The criticism certainly bothered him. Some of those people liked to use the word “selfish.”

“He was selfish. Cal’s streak was all about him.” I viewed it completely 100% the opposite way.

Bancells: They say that I was the athletic trainer that got Cal through all this, through all those games, and I'm always uncomfortable with that. Did he get injured during that time? Yes. Did I help him? Yes, as I would any other player in rehabbing their injuries. But it was all him. It was all his work ethic that got him to that point.

Palmeiro: The strike hurt the game so much. We lost so many fans. Sometimes those things are necessary, but the game was dying. We were killing the game.

Charles Steinberg, Orioles director of public relations: Before the strike hit, we had calculated when he would break the record. But when the strike occurred, everything got punted into this timeless abyss.

Schmuck: There was a time when it was projected to take place in Oakland. The Orioles at that time contacted the A’s and asked, if they got into that situation, for a schedule change. The A’s said no.

Steinberg: We didn’t know in November 1994 that the ’95 season would start when it did on April 26.

Schmuck: Then the season started late, and the date wound up falling in early September. But it was an interesting little controversy that bloomed out of all this.

Regan: Every city we went to, they were waiting for Cal, because they knew this was going to happen. Cal would always wait until the end of the series and sign. There might be 2,000 things he had to sign in a night. They had to kick him out of the stadium sometimes, shut off the lights. He was still signing autographs.

Ben McDonald, Orioles pitcher: The average fan can’t relate to a guy throwing 100 mph. But what they can relate to is a guy getting up every day and going to work.

Schmuck: This was the year that attendance crashed because fans were disenchanted. Cal Ripken brought the game back one autograph at a time. These lines would stretch back up to the concourse. Some stadiums asked him to stop doing it because those people were worried that that line forming in the seventh inning was obstructing the view from all these prime seats.

Steinberg: We recognized people would be traveling from all over the country and all over the world to see Camden Yards. We tracked the calls and the letters that came in. People didn’t necessarily just want to come for one day, and the tickets would be scarce. So just as we did for the All-Star Game in 1993, we made it All-Star Week. It was a five-day series of events. Streak Week was designed to give as many people who wanted to participate in some way the opportunity to do so.

Ripken Jr.: Twenty-five years is a long time. In some respects, it seems like it was yesterday. In other ways, it seems like another lifetime ago.

The Banner

To commemorate the anniversary in 2020, the Orioles superimposed digital 2130 and 2131 graphics on their famous Eutaw Street warehouse for a television audience. The images are iconic now, but the idea of celebrating the Iron Man’s achievement on brick was novel in 1995. And it almost didn’t come to pass. If you watched Ripken pass Gehrig, you remember the numbers on the warehouse. This is how they got there.

Jon Miller, Orioles broadcaster: When the team was home and the game became an official game, they put the rule up on the Jumbotron screen in center field, right from the rule book. And they had this music playing, a John Tesh instrumental song that was very uplifting -- and right as the music reached the crescendo, the new banner unfurled with the new number, which had now become official. So, they created the moment that normally a base hit or a strikeout or a home run would create for the all-time record.

Spiro Alafassos, Orioles director of ballpark entertainment and special events: The concept came earlier that summer. I was watching Eddie Murray’s countdown to 3,000 hits with the Indians. Down the left-field line, they had a bridge or walkway and they hung some banners, and they’d count up every time Eddie got another hit toward 3,000. At that point, we’d been planning 2,131. We thought it would be neat on a bigger scale. The warehouse is the perfect canvas.

Steinberg: Cal’s family wouldn’t want it to be over the top, right? They are beautifully humble. They are undeniably modest. So, this was not going to be like a royal coronation as much as we want, because that’s how much we were proud of them. You had to strike a balance.

Alafassos: I remember going to ownership and Mr. (Peter) Angelos being vehement about nothing going on the warehouse. His fear was if we started hanging stuff on the warehouse, before you know it, the sales guy would want to have sponsorships on it. He wanted to keep it pristine.

Steinberg: How do you involve everyone in an international celebration and respect humility and modesty? It’s a challenge.

Alafassos: The idea got rejected. I went back to my office and sulked. And then John Maroon, who was the PR director at the time, said: “We’re going to fight for this. It’s a great idea.” So, we went up to John Angelos’ office, and he listened. He took the idea to Mr. Angelos, and the next morning we were a go.

Palmeiro: Every night that we went to the ballpark and saw the numbers coming down one at a time, it just felt like a volcano that was about to erupt.

Every night that we went to the ballpark and saw the numbers coming down one at a time, it just felt like a volcano that was about to erupt.

Rafael Palmeiro

Alafassos: So now it was a matter of how do we execute this? We worked with a signage company called F.W. Haxel that hung our bunting for Opening Day every year. They could make the signs, but they wanted to bring a crane out and literally have a crane on Eutaw Street for every one of these games. We said no. We came up with a solution basically using paper clips, big binder clips. Instead of a crane, we rolled it up like you would a mat, clipped it on both sides, and threw some rope down through one of the windows. We did some tests, it worked and the rest is baseball history.

Regan: It kept building up and building up. You were always aware of it, but the excitement really came in the last 10 days before he broke the record.

Alafassos: Even if you weren't going to go to game number 2,130 or 2,131, it gives you a chance to celebrate Cal’s accomplishment if you came to any of those other games. So, it became a moment every single night.

Miller: It was ingenious.

The Stage

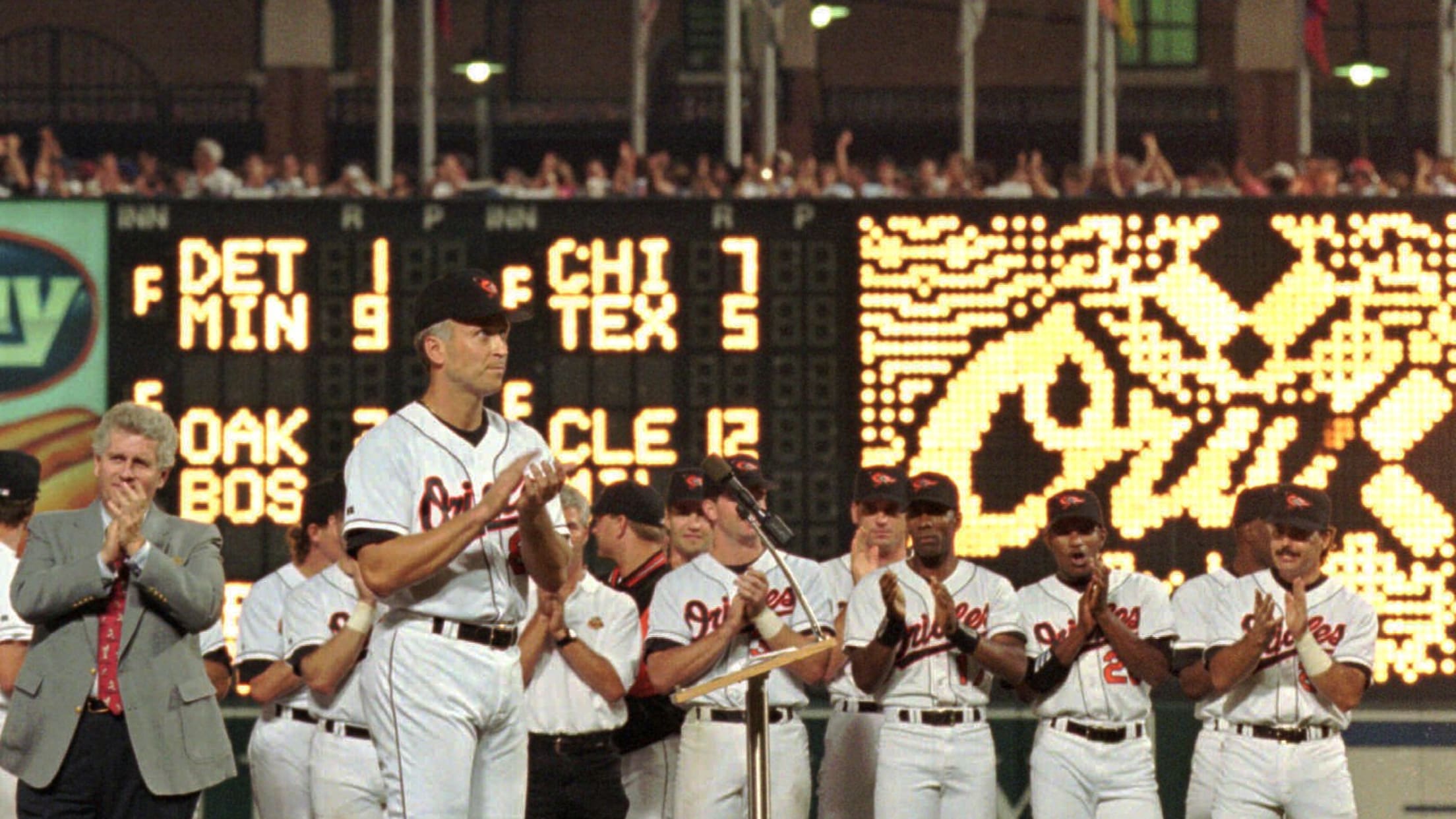

On Sept. 5, 46,804 fans jammed Camden Yards to see Ripken tie Gehrig’s mark. The official count the next night was 46,272; millions more tuned in to the national telecast. But on the ground, it was largely a family affair: Ripken’s young children, Rachel, 5, and Ryan, 2, threw out the first ball from the stands beside the home dugout. And the Baltimore crowd celebrated the national star from Aberdeen, Md., like what he was: a hometown hero who never left.

Regan: The night that it happened, there were so many people there. Once the game started, there was a roar the whole time. When he broke the record, the fans were just unbelievable. There were giant tears in my eyes.

McDonald: The atmosphere in the ballpark leading up to that night, it was like you could cut it almost.

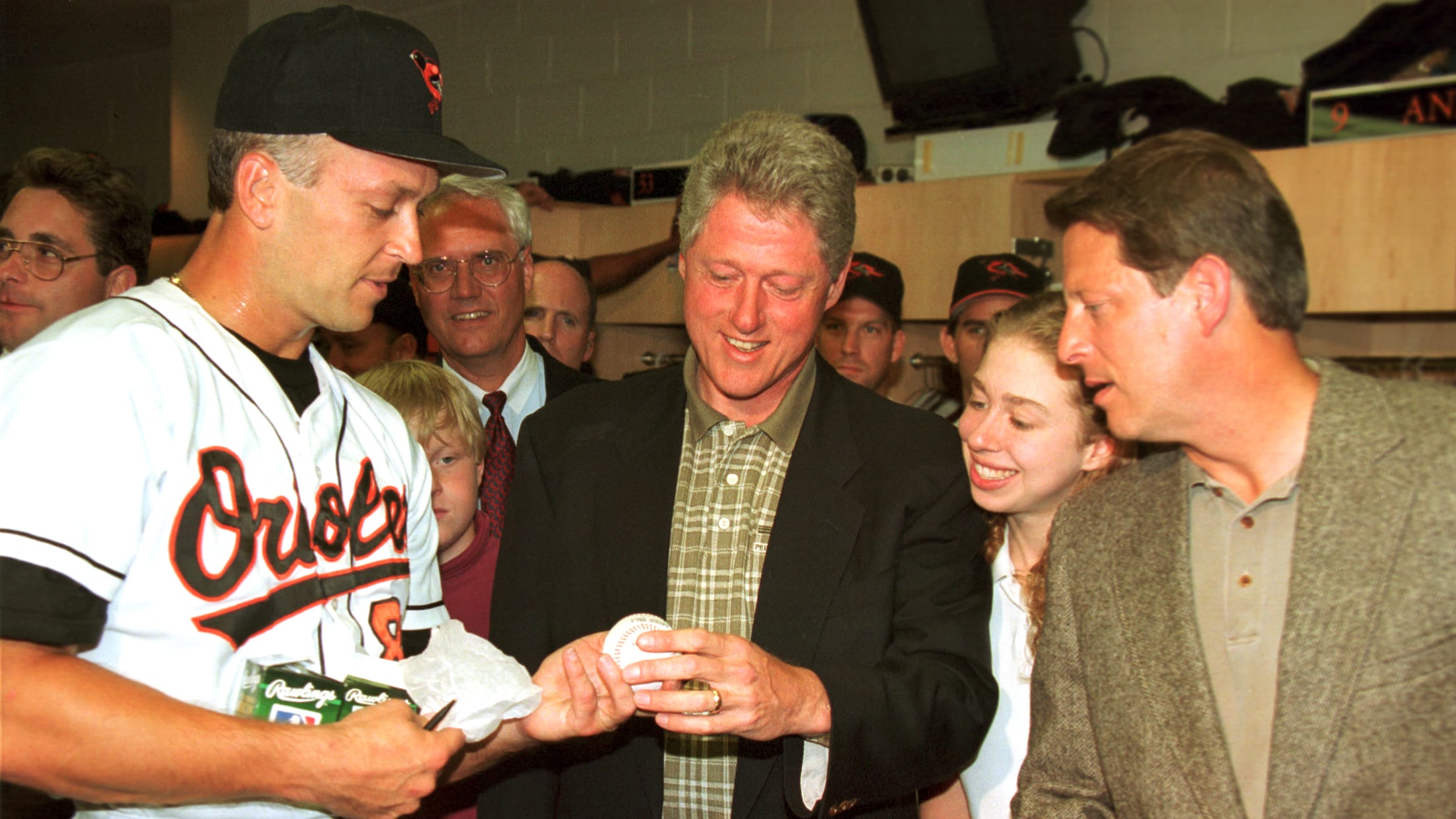

Miller: The President (Bill Clinton) was there; the Vice President (Al Gore) was there. Joe DiMaggio was there. There were so many major dignitaries there.

Schmuck: DiMaggio is up there with Ernie Banks and Cal’s family in the box. Then his wife and kids were down by the screen. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

Bill Clinton, 42nd U.S. President: I remember being at Camden Yards 25 years ago watching Cal Ripken break the record like it was yesterday. I always loved watching Cal play and admired him for his discipline and devotion to his craft, his teammates and his community.

Regan: Instead of a triplet of lineup cards like normally, the American League gave me six copies of it to write through. You gave one to the umpire. One to the other manager. I got one. One went to the Babe Ruth Museum, and one went to the Hall of Fame. I think Cal got the other one. Everything was so much bigger for this game.

Miller: The David Letterman show called me and asked if I could do a live shot from the batting cage [that] they could play later that night. … It got a big laugh.

McDonald: I had a sore shoulder and I was getting close to coming back. Phil Regan called me into his office three days before Cal was going to break the record and said they were sending me on a rehab assignment to Rochester, N.Y. We were 25 games out of first place. I said you want me to go pitch in a rehab game when the greatest record in the history of baseball is about to be broken? You can fine me. You can do whatever you want to. But I’m not going.

Ripken Jr.: People tell me all the time they were at the record-breaking game. It feels like a heck of a lot more than 44,000 people tell me that.

Regan: I was the pitching coach for Team USA when we won the gold medal at the 2000 Olympics. I always thought that was a big event. But I don’t think anything really tops the night Cal broke that record.

Bancells: One day when the streak was becoming an issue, I was taping his ankles and he said to me: "I don’t really get the big deal of all this. What about you? You come to work every day. You've been here taping my ankles every day. So, what’s the big deal?"

Ripken Jr.: I recently rewatched the whole broadcast for ESPN. (Former O’s manager) Earl Weaver was interviewed during the game, and he said when he moved me to shortstop, he was just hoping to get through the weekend. So that was different.

The Homer

Throughout his career, Ripken often elevated his play to match the moment. His flair for the dramatic on this night required building suspense: Ripken fouled out in the second inning and started a double play behind Mike Mussina in the fourth. But besides that, he played a rather uneventful role early.

By the time he stepped in against Shawn Boskie in the fourth, the Orioles had gotten solo homers from Palmeiro and Bonilla to take a 2-1 lead.

Shawn Boskie, Angels starting pitcher: Going back to Spring Training, there was a group of us sitting around when they passed out the schedule. Someone mentioned we were going to be in Baltimore when Cal was going to break the record. But this was still 130 games away. We thought it was cool we would be there. I never imagined I would be the pitcher for that game.

Ripken Jr.: The Angels were in the middle of their pennant race and we were not. It was important for us to play well and for me to do well.

Boskie: Warming up, I had so much adrenaline flowing, my first five pitches in the bullpen had the catcher diving all over the place. I had to step off the mound and take a couple breaths. There was nothing routine about it.

Ripken Jr.: Mike Mussina gave me a batting tip in game 2,129, and I hit a homer off Jim Abbott. The next game I hit a homer again. So, when 2,131 came up, controlling your adrenaline was important and I was pretty good at doing that. But I also felt like my swing was coming in the zone.

Boskie: I recall flashbulbs from all the cameras going off when Cal came to the plate. It was blinding.

Billy Ripken: I sat up in the box for the first three innings and went down to the seats behind home plate in the middle innings. Part of that was because I knew something was going to happen.

Schmuck: You could wonder if somebody threw a ball straight on purpose. There are always going to be people that think that. I don’t buy it. I think Cal rose to the occasion.

Boskie: It was a 3-0 count. And I was trying to decide if I really needed to make a great pitch or not, and I never actually made a decision on that. And so, I just threw a ball down the middle that I wanted to be a strike.

Miller: I’ll never forget the home run, because President Clinton was on the radio with me at the time. I made a lame joke about Cal being in a 3-0 count, how he should send a presidential order to the Angels to throw a strike for the good of the game and the good of the country. But on the other hand, I said, if he grooves him a strike right here … and then the president interjected and said: "Then he’ll hit it a long way!" And as soon as he said that the pitch came in and, boom, Cal hit it a long way.

Boskie: I am glad I got to be a part of it. It’s a highlight of my career.

Regan: What else can you do? You’re going to break the record and hit a home run the night you do it? Really?

Boskie: Jim Abbott said to me afterwards: "Dude, that was awesome. I know nobody wants to give up a home run, but that was amazing."

The Lap

What happened next remains one of the most iconic sequences in baseball history. Boskie retired the next three hitters, and Mussina sent the Angels down 1-2-3 in top of the fifth. Mussina got Angels second baseman Damion Easley to pop out to end the frame, making the game official. The baseball world’s attention then shifted to the warehouse.

Regan: The whole thing was a climax when that banner dropped. Then, guys were standing, cheering and crying. There were a lot of tears in the clubhouse that night. It was a release of what we knew was happening all year long.

Miller: It was the longest ovation I ever heard. Maybe the longest ovation in the history of sports.

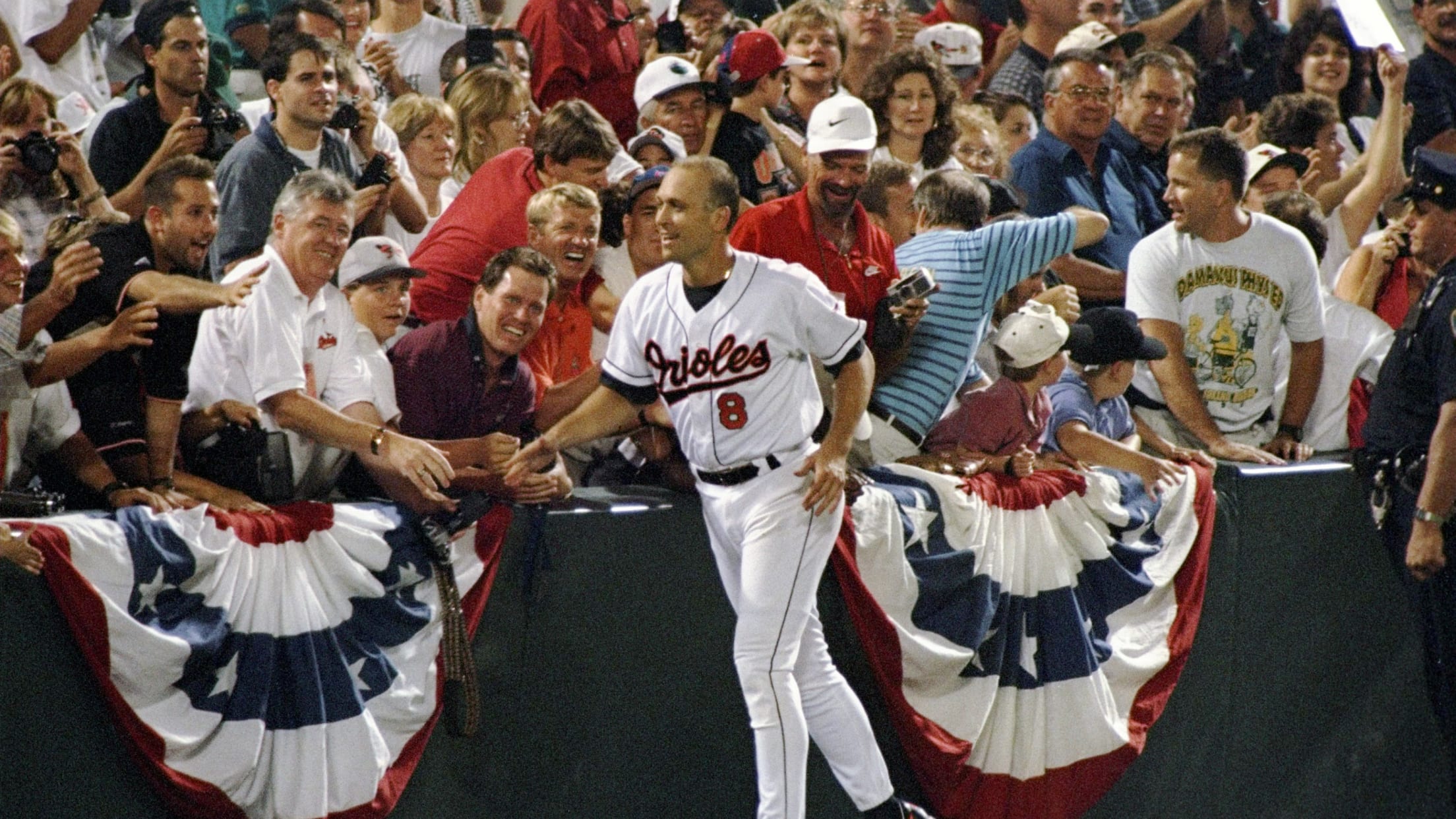

Ripken Jr.: There was a point in time during the lap where I started to think: “I don’t care if this game happens at all again.” But all the way until that point I was thinking, “I’ll celebrate after, but we have to get the game going.” It was like an unintended rain delay.

Miller: Cal had told everybody, “I'm not going to have any stoppage of the game. I'm not going to stand for that. After the game, I'll be happy to stay through whatever ceremonies you want to have or whatever, but the game itself must continue to be played.”

Alafassos: Cal wanted nothing to do with banner dropping, because he didn't want the game to stop. But even he admitted later that he started getting goosebumps.

Ripken Jr.: Looking up at my dad, all kinds of different feelings went through me. Here was a guy who was old school about pretty much everything, including sharing his feelings as a parent. He didn’t really go around saying, ”I love you,” but you knew he did. In that moment where I looked up, it was probably just a few seconds, but it felt like a thousand words were flying back between him and I.

The ovation officially paused play for 22 minutes and 15 seconds. The first thing Ripken did was visit his family at the seats behind home plate and give them his jersey. He was called out of the dugout three separate times before the crowd began chanting “We! Want! Cal!”

Billy Ripken: I make jokes about how he made us all stand for 22 minutes. But it was really just unbelievable.

Bonilla: The fans were so proud they were just not going to stop applauding him. They could’ve applauded for an hour, they were so into it.

Palmeiro: I said, “Look, man, these fans are not going to stop as long as we sit here. The game's not going to start, and I know you want the game to start. We're gonna sit here for hours if you don't get out there.”

Ripken Jr.: Rafael Palmeiro was the first to say, you’ve got to take a lap around this ballpark. And I dismissed it totally. Then Bobby Bonilla, with his big boisterous voice, took control of that. Jeffrey Hammonds was close by, too. Once I was physically starting to be pushed down the line, I thought, “OK, let’s go.”

Schmuck: There's no reason to think it wasn't spontaneous, except that it was so perfect.

Ripken Jr.: No one could have choreographed it to happen any better than it did.

Miller: What we didn't realize until later was that Cal was sick. He was running a fever. He was hardly getting any sleep. He was still insisting on getting up early in the morning and having breakfast with his kids and taking them to school and all the other stuff that was swirling around it. So, he was exhausted. They told him he had to go out and acknowledge the people and go out and run a lap, for everybody. And he said, “I won't make it. I’m too exhausted, I won't make it around the field.”

Billy Ripken: It was the entire city of Baltimore celebrating this moment, but it also turned into all of baseball and everything associated with baseball, celebrating Junior.

Bancells: When it came to work ethic, I think it really spoke to the fireman, the policeman, the electrician, the person who just goes out and does their job every day.

Clinton: He paid attention to the little things and focused on what was best for the team in every situation -- a winning strategy in baseball and in life.

Steinberg: The seeds of love and healing were sown when Cal took that victory lap and touched people along the way. You had the belief restored once again in the relationship between players and fans and the players and the game. It was a big deal.

McDonald: It’s really a highlight of my career. It’s right at the top of everything I ever did, just to be a part of that and witness it firsthand.

Regan: I’ve seen a lot. I saw Roger Clemens break the American League record for strikeouts. I was the pitching coach in Chicago when Kerry Wood struck out 20. I was down in St. Louis with the Cubs as a pitching coach when (Mark) McGwire broke the home run record. This was even bigger than all of those things.

Billy Ripken: It was almost like you weren’t really there watching it live, because it was something that you would only see in a movie. It just didn’t stop.

It was almost like you weren’t really there watching it live, because it was something that you would only see in a movie. It just didn’t stop.

Billy Ripken

Steinberg: You can watch it on so many levels. You can watch it like baseball and like abstract art.

McDonald: Everybody talks about Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire bringing people back to baseball after the work stoppage in ’94. But it was Junior who brought people back. Cal Ripken Jr. saved baseball.

The Epilogue

Ripken would play 501 more games in a row before voluntarily ending the streak at 2,632. He did not miss a game from May 30, 1982, to Sept. 19, 1998, a stretch that spanned 17 years, nine managers and three U.S. presidencies. He retired in 2001, at age 40, and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007 on the first ballot. A record 75,000 people attended his induction ceremony in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Since Ripken, no player has come within 1,480 games of his record.

Regan: When you think about the streak, it’s almost impossible.

Bonilla: It’s just mind-boggling. I still marvel at the feat.

Ripken Jr.: A logical understanding would say that if I can do it, certainly somebody else can, too. But it takes a commitment over a long period of time. It takes the right support and ideology. There was an honor in playing 162.

Billy Ripken: I know what he’ll say: "If I can do it, someone else can, too." That’s just wrong. No one will ever play that many games in a row again. It’s just not going to happen.

Boskie: I have a ticket from that game framed with the ball, and I also got a lithograph that was done of the game that shows the field and the sign and him hitting the home run off me. Cal signed that for me the next year, which is really cool. It's probably my favorite piece of memorabilia that I have.

He was gracious to write: "Always a great battle, Cal Ripken."