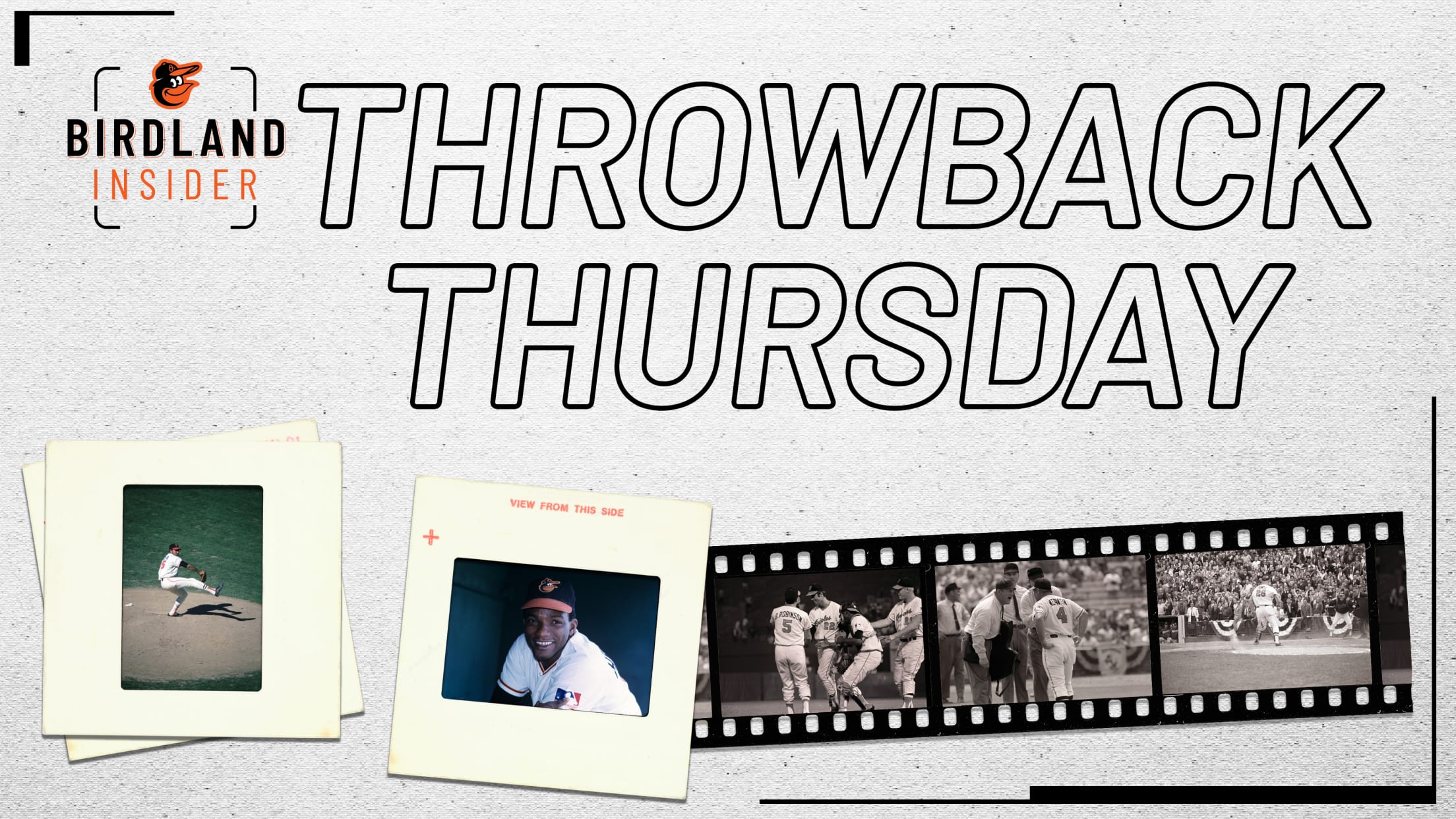

1969: Dawn of the O's greatest era

It was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, when a man walked on the moon for the first time and “more than half a million strong” filled a farm in upstate New York for a music and arts fair called Woodstock.

It was the summer of ’69, and the country was going through some changes. Sesame Street began teaching pre-school kids and a hip new comic strip called “Doonesbury” began giving many of their parents a chuckle. A Baltimore band, The Peppermint Rainbow, would debut on the Billboard pop charts in March with a top-20 song, “Will You Be Staying After Sunday.” The quintet would play a post-game, bullpen concert following an Orioles game at Memorial Stadium in August; they would not be staying after fall.

Baseball also was going through changes in 1969. The Major Leagues had expanded for only the second time, to 24 teams, and for the first time, the American and National Leagues had been divided into divisions. That meant that for the first time, having the best record in the league would not lead automatically to the World Series; the top teams in each division would face off for the league title and the right to advance.

In Baltimore, the Orioles were quickly putting distance between themselves and the rest of the new AL Eastern Division, racing to a 20-8 record in early May. They lost back-to-back games only once before May 4, and lost three-straight games just twice before late August. They endured one four-game losing streak at the end of August (and still led the division by 14 games when the streak ended) and a five-game losing skid in the final week of the season.

By the end of June, the Orioles had an 11-game lead. They won their first seven games after the All-Star break to take a 15-game lead into August. On September 13, minutes before they recorded the final out in a 10-5 win over Cleveland for their 101st victory, the Orioles clinched the first AL Eastern Division title when the Tigers lost to the Washington Senators.

They finished with a 109-53 record, the best in the majors, and swept the Minnesota Twins – winners of the AL Western Division – in three straight games, advancing to the World Series against the New York Mets, who had been ridiculed for through most of their first seven years of existence, averaging just 56 wins per season. Now, they were the first expansion team to reach the Postseason, and although they won 100 games and dispatched the Atlanta Braves in the first National League Championship Series, the Mets were supposed to be no match for the hitting, pitching, and fielding of the Orioles.

But for Baltimore, being heavily favored against New York – especially in 1969 – was no lock. Many of the Orioles players remembered being the overwhelming underdogs three years earlier in the franchise’s first World Series against Los Angeles, when the Birds swept the favored Dodgers in four games. Perhaps more importantly, however, were the two cataclysmic sports events that had taken place earlier in the year between teams from these same two cities.

On January 12, the Baltimore Colts played the New York Jets in the third AFL-NFL Championship Game – the first to be called “the Super Bowl.” The Colts had gone 13-1 during the regular season and avenged their only loss by beating the Cleveland Browns, 34-0, for the NFL title. They were 18-point favorites to make it three in a row for NFL teams against the AFL, but Joe Namath’s prediction of an upset came true and the Jets shocked the football world, beating the Colts, 16-7. Nowhere was the hurt felt worse than in Baltimore.

Less than three months later, teams from the two eastern seaboard cities met again in post-season play, this time on the hardwood court. The Baltimore Bullets had the NBA’s best record (57-25) when they faced the New York Knicks in the first round of the Eastern Division playoffs. But in a week’s time, the Knicks methodically dispatched the Bullets, sweeping a four-game series to send Baltimore to a second defeat against a New York team.

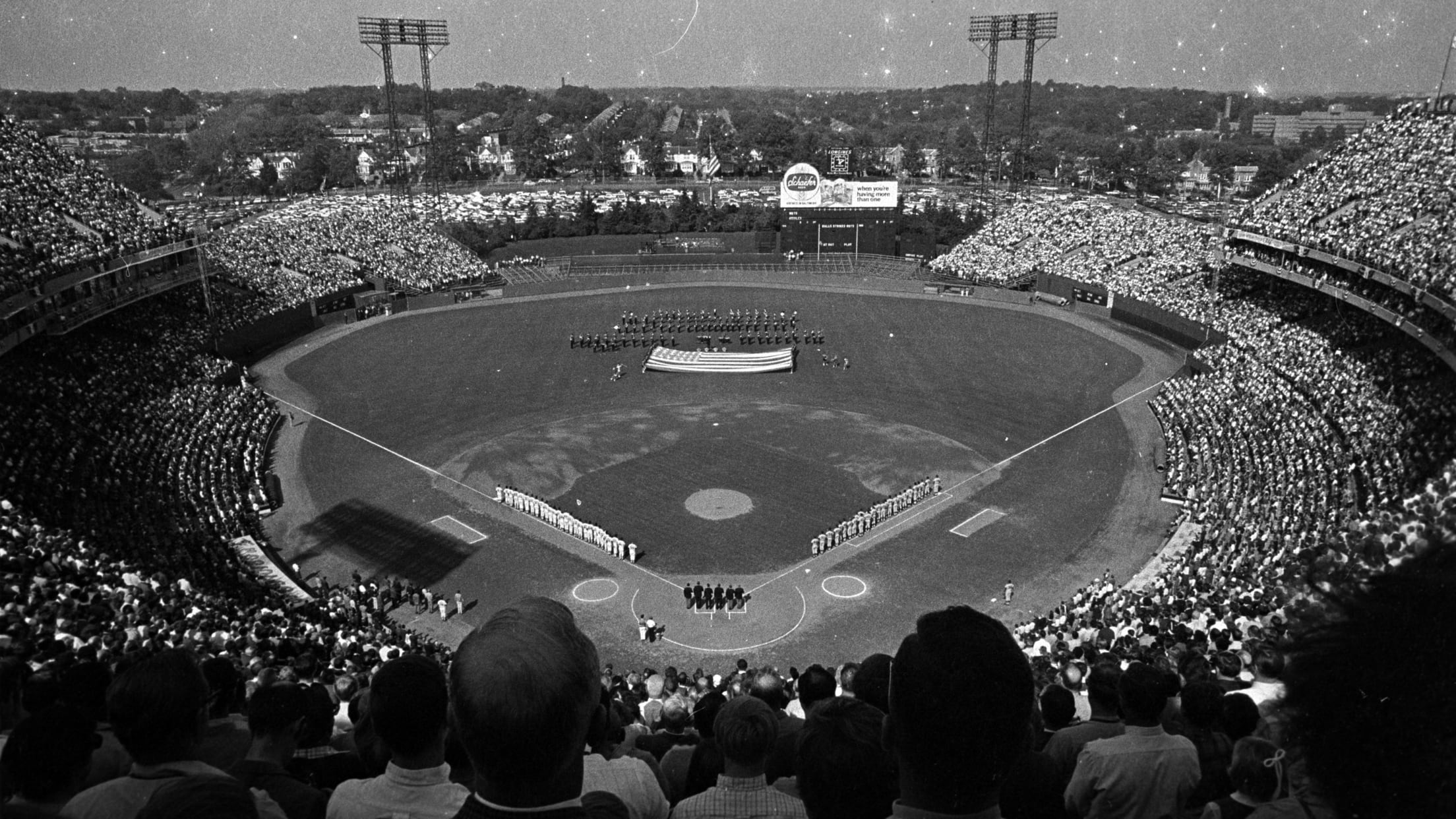

Six days after the Bullets’ final defeat, the Orioles – with high expectations coming off a second-place finish the year before – began their season with a 5-4 loss to the Boston Red Sox in 12 innings at Memorial Stadium. It would be the last blip before October.

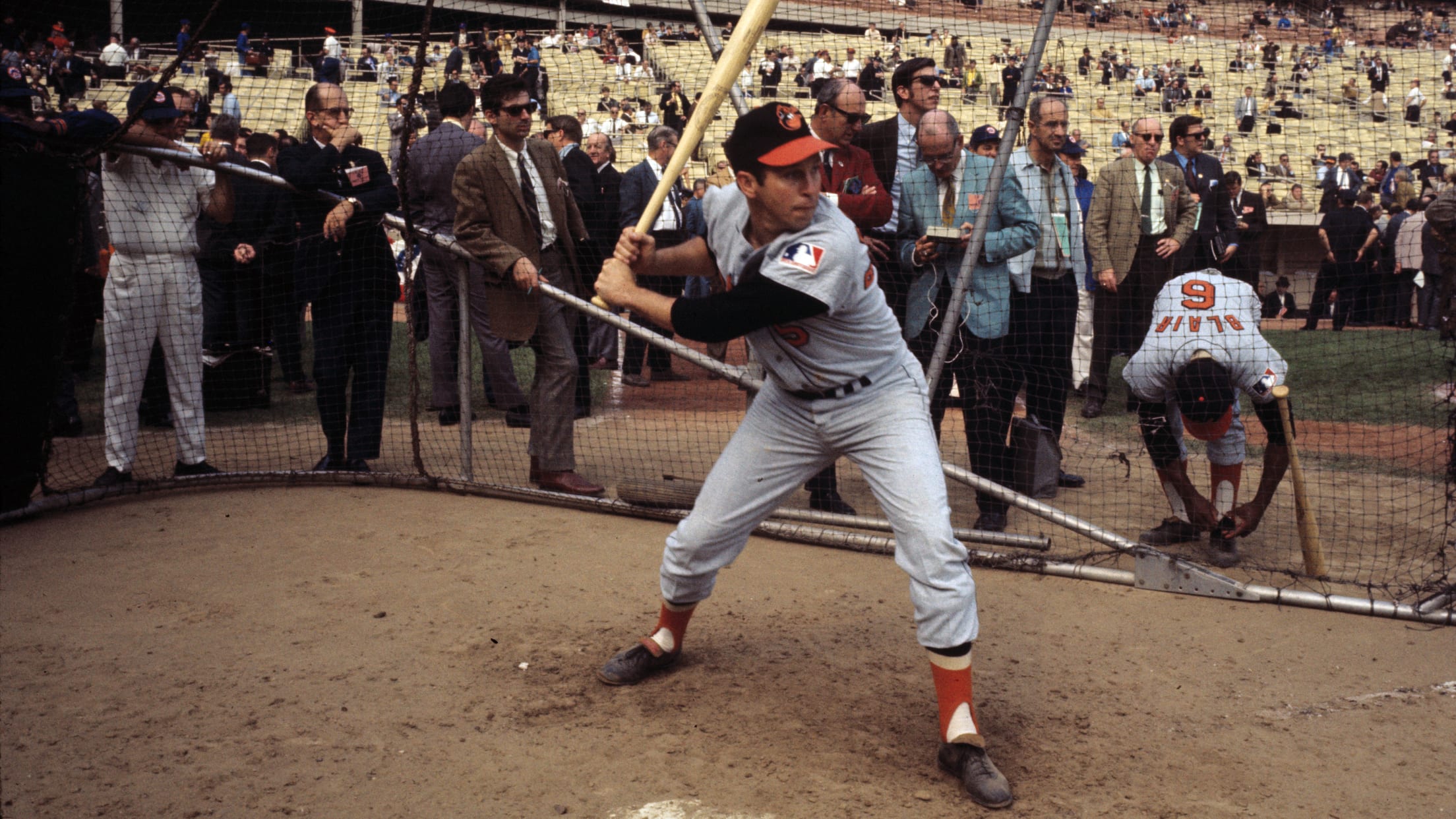

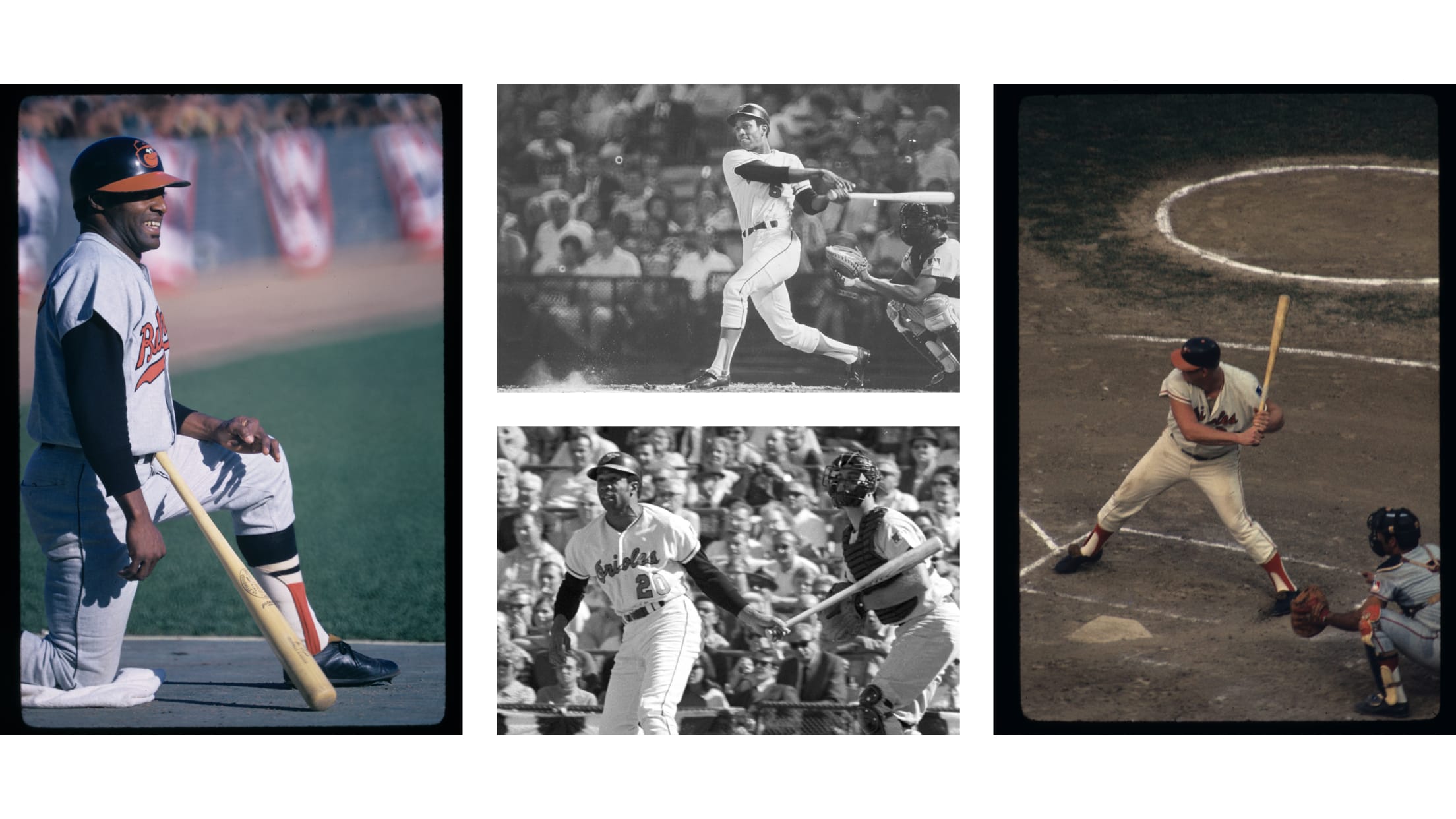

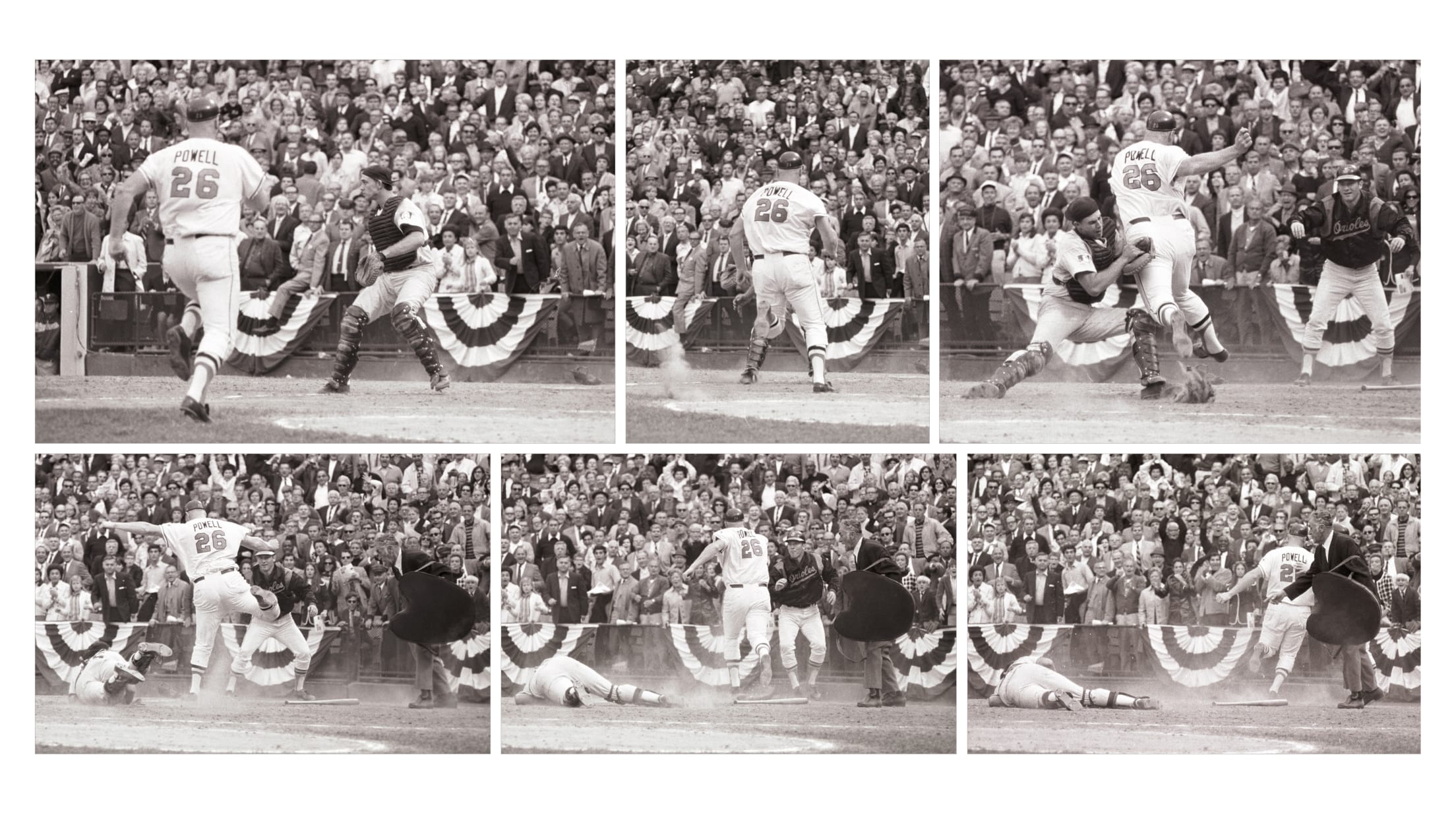

The core of the team that finished a distant second, 12-games behind pennant winning Detroit in 1968, returned, with several players rebounding from off years. After batting a combined .242 with 35 homers and 140 RBI in ’67-’68, first baseman Boog Powell (.304-37-121) returned to his 1966 form. Right fielder Frank Robinson, who suffered double-vision since a mid-1967 collision on the bases and had the lowest homer and RBI totals of his Major League career in ’68, finally could see clearly and batted .308 with 32 homers and 100 RBI. Powell and Robinson finished second and third, respectively, in AL Most Valuable Player Award voting (behind Minnesota’s Harmon Killebrew). After batting just .211 in ’68, center fielder Paul Blair (.285-26-77) had the best year of his career, and left fielder Don Buford (.291, 99 runs scored) led AL lead-off men with a .397 on-base percentage.

Seemingly everywhere you looked, there was gold. In addition to the indomitable Brooks Robinson (10th of 16 straight) at third base, second baseman Davey Johnson and shortstop Mark Belanger won their first Gold Gloves, as did Blair in the outfield. As a team, the Orioles committed 21 fewer errors than the next closest team in the league.

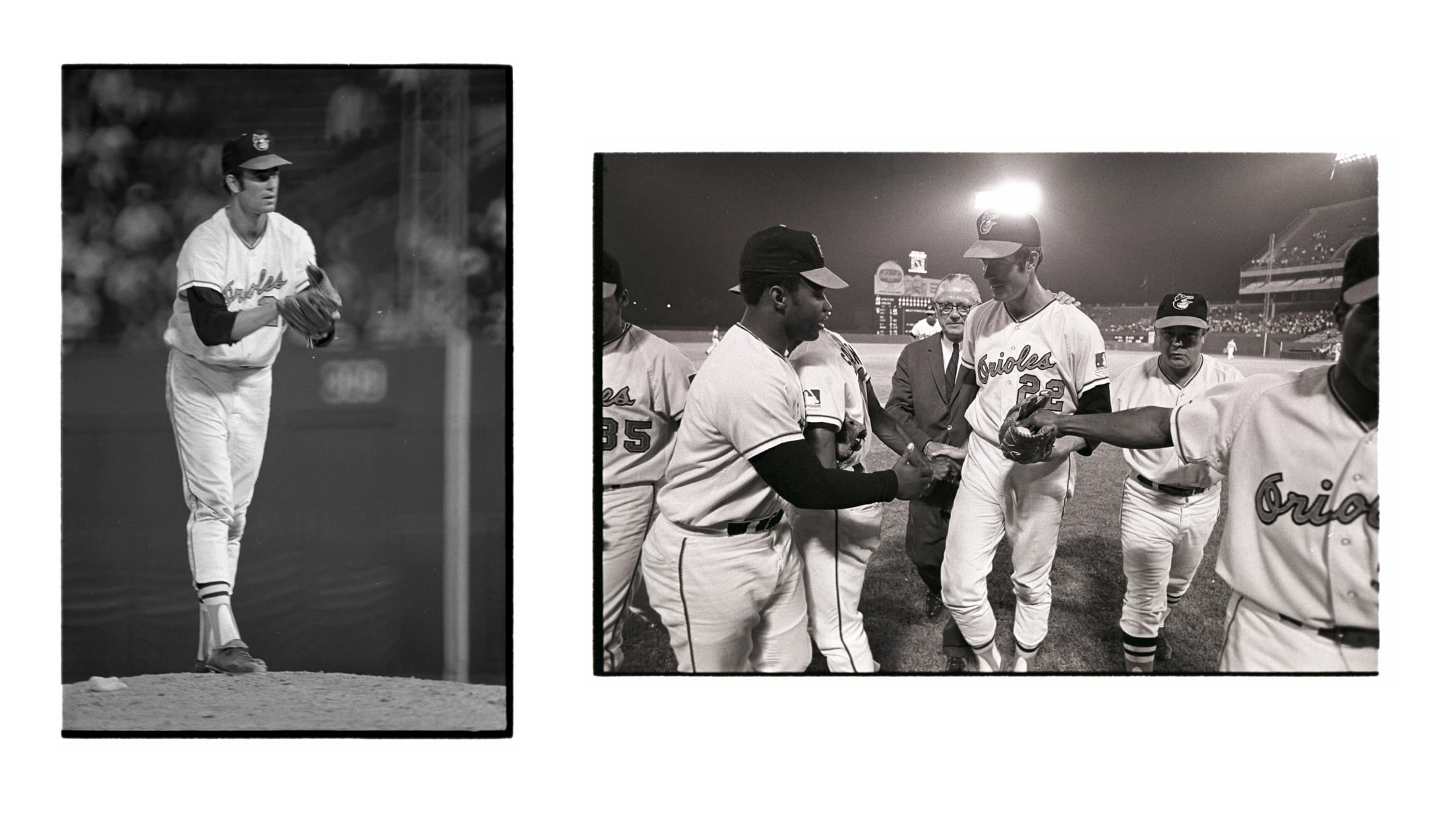

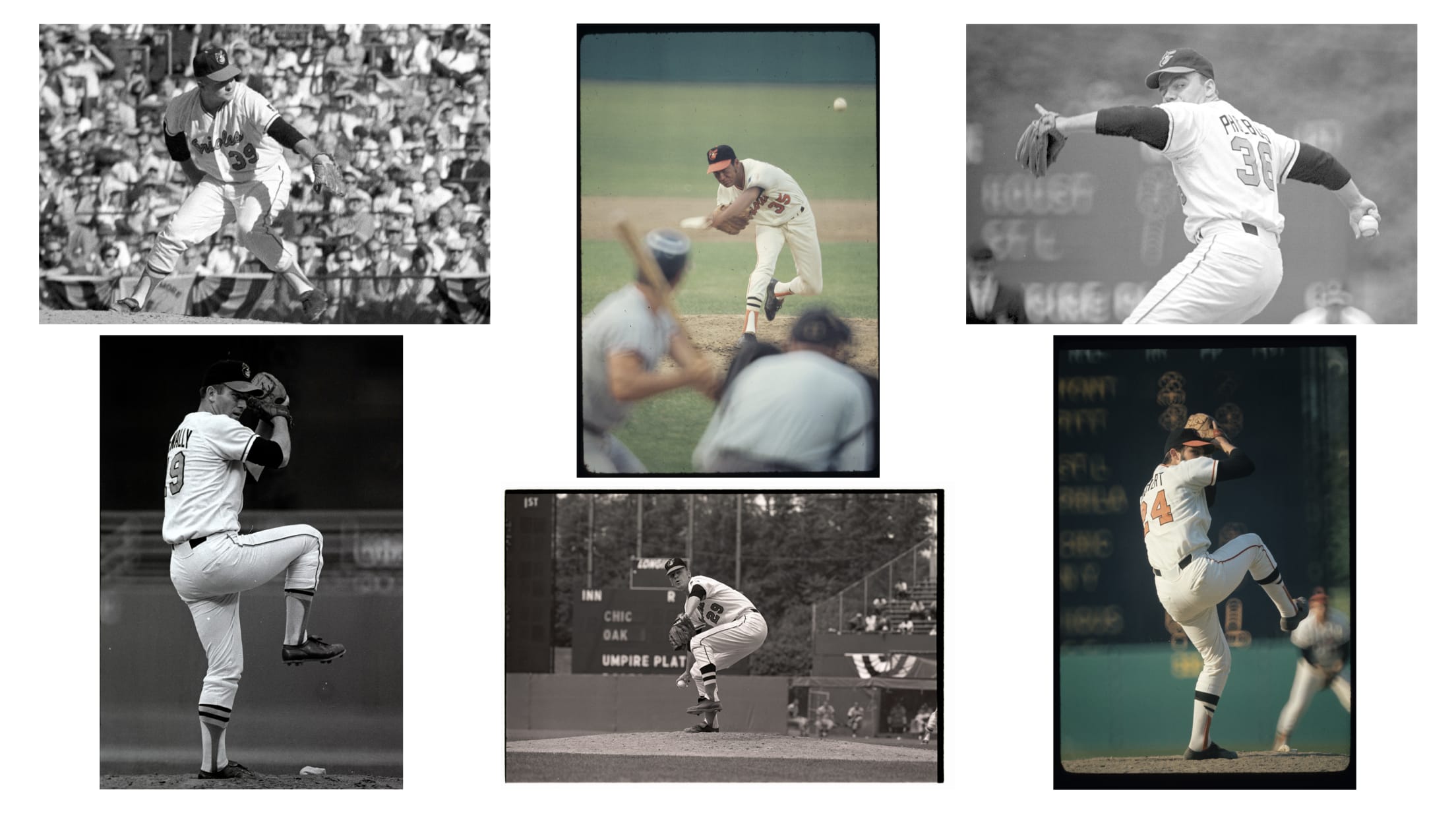

All that hitting and defense might have been enough, even if the Orioles didn’t have one of the league’s best pitching staffs. Left-hander Dave McNally was a 20-game winner for the second time. Baltimore-born Tom Phoebus won 14 games for the third year in a row. Jim Palmer, after missing most of the previous two seasons with a potential career-ending arm injury, returned and went 16-4; including a no-hitter on August 13, four days after returning from a six-week stay on the disabled list. It was the addition of crafty left-hander Mike Cuellar, acquired during the off-season from Houston, which spelled the real difference. Cuellar went 23-11 and shared the Cy Young Award with Detroit’s Denny McLain.

Cuellar (32) and reliever Dick Hall (38) were the only pitchers older than 29. But Hall, along with Eddie Watt, Pete Richert and Dave Leonhard, formed a formidable bullpen, as each of the quartet had an ERA under 2.50.

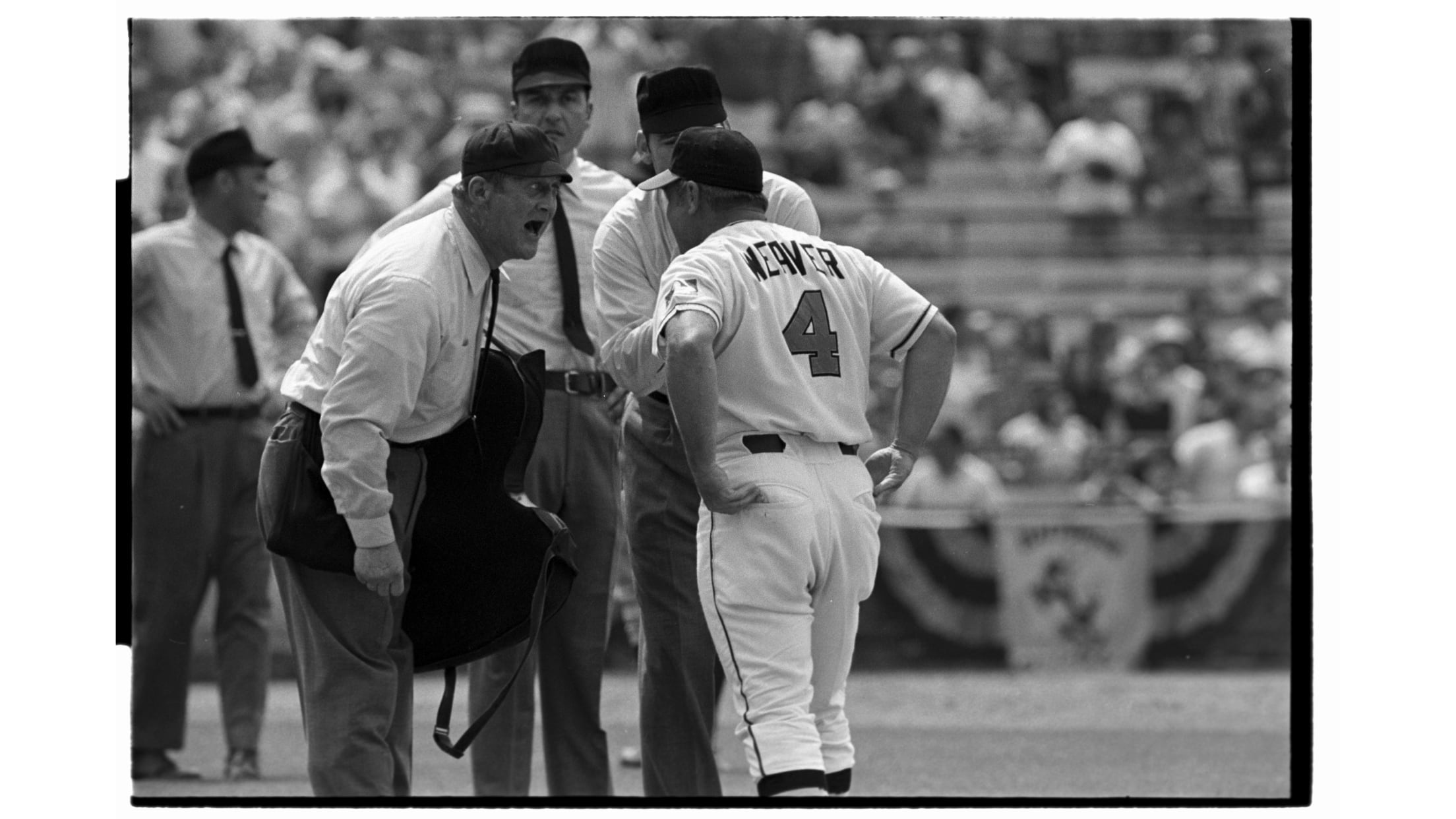

And in the dugout, Earl Weaver already was becoming a legend. In only his second full season as manager, Weaver was figuring out how to get the most out of his players, while at the same time wearing out umpires and staying two innings ahead of opposing skippers. He had plenty of talent, to be sure, but Weaver coaxed 18 homers and 70 RBI from his trio of catchers (Elrod Hendricks, Andy Etchebarren and Clay Dalrymple) and seemed to always know when to plug reserves and role players like Merv Rettenmund, Dave May, and Chico Salmon into the lineup.

The Orioles carried baseball’s best record into the Postseason. But unlike every previous title-clinching in Major League history, the Orioles were not assured of going to the World Series. Despite being 12 games better during the regular season, they had to play AL Western Division’s best team, the Minnesota Twins, in a best-of-five series for the league championship.

The first two games of the new AL Championship Series, played at Memorial Stadium, were everything baseball had hoped in setting up divisional play. Powell’s homer in the bottom of the 9th inning tied Game 1, and in the 12th inning, Paul Blair’s surprise two-out bunt brought Mark Belanger home from third to give the Orioles a 4-3 win. The next day, McNally worked 11.0 shutout innings before Curt Motton’s pinch-hit single scored Powell for a 1-0 victory.

When the series shifted to Minnesota for Game 3, the Orioles dispensed with the drama early. Blair went 5-for-6 with five RBI and Palmer pitched a complete game, 11-2 victory to give the Orioles a sweep. Though the first two games were nail-biters, it all seemed pre-ordained. Plans were made for a victory parade through the downtown streets – to take place on the day before the World Series was to start.

The World Series against the Mets, who had also swept the Atlanta Braves in the National League Championship Series, began at Memorial Stadium. It looked like the predictions of an easy Orioles title run were correct when Buford led off the bottom of the first inning of Game 1 with a home run off Tom Seaver. The Orioles scored three more runs in the 4th and Cuellar’s complete game gave the Orioles a 4-1 win.

No one could have predicted that would be the Orioles’ last win of the season, even after Jerry Koosman held the Orioles hitless through six innings of Game 2. The Mets broke through with the go-ahead run in the 9th to win 2-1, and the series shifted to New York knotted at one game apiece.

All sorts of strange things seemed to happen once the games started at Shea Stadium: Tommie Agee homered to lead off the first game there, equaling Buford’s feat in Game 1; the sure-handed Orioles committed as many errors as they scored runs (four) in the three road games – and two of the miscues led to damaging runs; Baltimore-born Mets right fielder Ron Swoboda, not known for his defense, suddenly was chasing down line drives in the gaps and turning potential game-tying hits into game-changing outs; a spot of shoe polish turned a possible Cleon Jones strikeout into a hit batter, seemingly unnerving the Orioles enough to allow a two-run homer to follow.

By the time Jones nestled Davey Johnson’s fly ball into his glove in left field for the final out in Game 5, the Mets’ – and New York’s – karma over the Orioles had spread. As dominating and exciting as it had been, the year would not end in the ultimate triumph for Baltimore.

Any number of hit songs from that year could have served as the Orioles’ theme song for the season. What started out as “Hot Fun in the Summertime” turned into the “Worst That Could Happen.” And though it “Hurt So Bad,” the Orioles vowed to “Get Back.”

They would get back. And in the end, 1969 turned out to be the start of the greatest three-year run in club history.

This story was originally published in the 2009 First Edition of Orioles Magazine. Birdland Insider features original content from Orioles Magazine, including new articles and stories from our archives.