The Bahamas is no longer a baseball secret

Around 10 years ago, Marlins rookie infielder Jazz Chisholm Jr. sent a Facebook message to Antoan Richardson asking for some bats. Chisholm, then a high schooler at Life Prep Academy in Wichita, Kansas, had known the professional ballplayer growing up in the Bahamas. When the bats arrived, Chisholm texted a thank you -- as well as a promise. The teenager had just watched Brock Holt and the Red Sox at Fenway Park. The bright lights and big stage had painted a clear vision: I'm going to play in the big leagues.

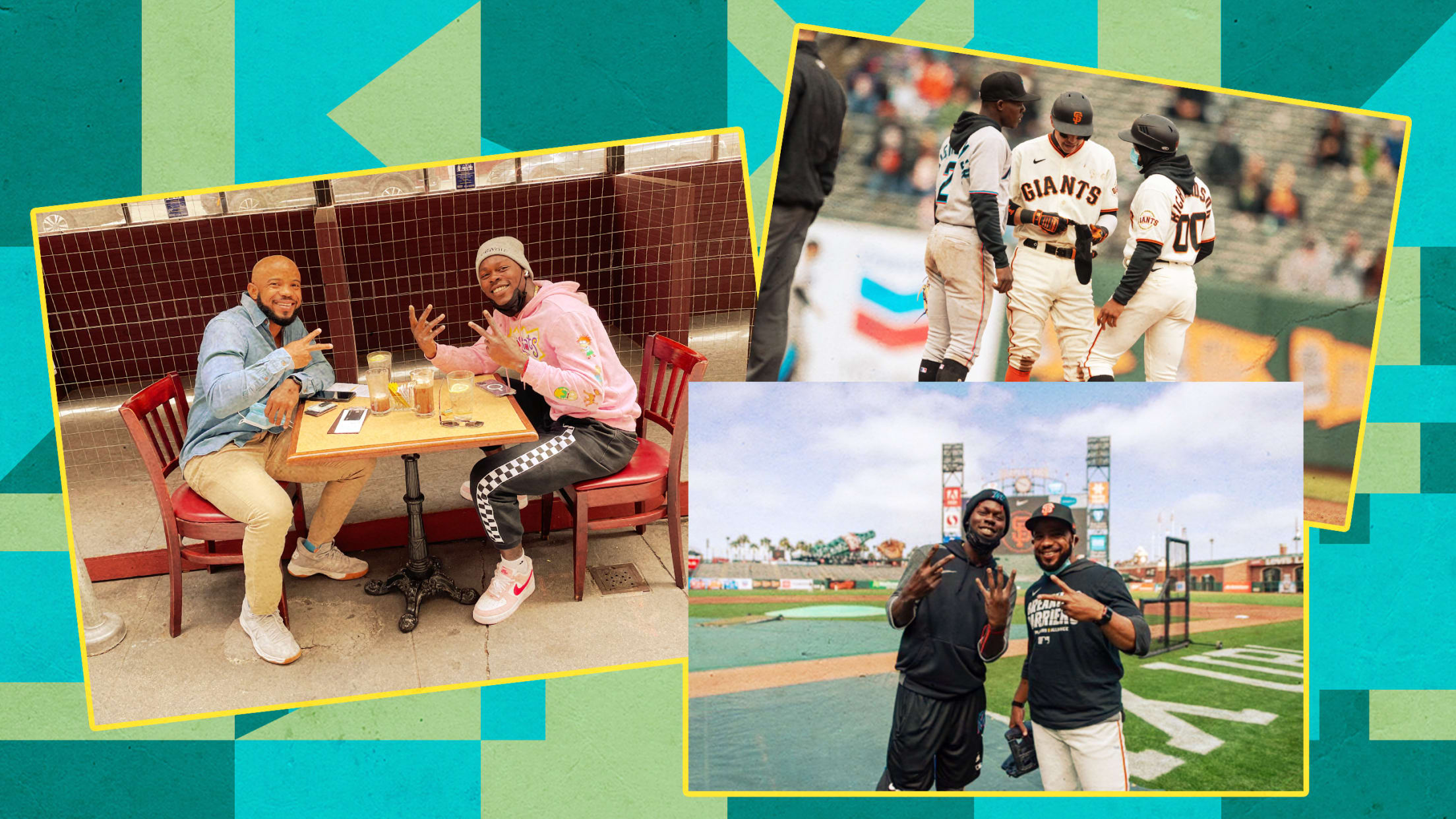

Chisholm became the seventh Bahamian to reach the Majors when he debuted on Sept. 1, 2020, and the first since Richardson's final game on Sept. 28, 2014, with the Yankees. On April 1, 2021, Chisholm, a native of Nassau, was the first player born in the Bahamas to appear on an Opening Day roster since MLB began releasing the annual data. So when the Marlins visited San Francisco -- where Richardson is the first-base coach -- for a four-game set in April, Chisholm and Richardson grabbed lunch to celebrate the occasion.

"I just reflect on that moment and that time, and then watch that come to fruition right now," Richardson said. "I'm just happy that he's able to live that dream, because the reality of it is like, we as young Bahamians in the sport of baseball, we probably haven't had the opportunity to dream about it as big as others, just because we haven't seen it in this generation."

Richardson is happy to see Chisholm reach the big leagues, happy to see another player from the Bahamas make that extra push, happy to witness Chisholm's star turn. And he expects others aren’t far behind.

"I don't have a better word, and I'm just really, really happy to witness this happen, and then equally as excited for what is about to happen,” Richardson said. “There are so many more Bahamian guys. I know myself and Jazz -- we talked about how we've invested into the community to make sure that number is eight sooner than later."

Baseball on the backburner

Made up of nearly 700 islands and cays, the Bahamas is located on the northwestern edge of the West Indies. Formerly a British Colony, it became an independent country within the Commonwealth in 1973. The Bahamas stretches more than 500 miles southeast to northwest, and lies about 60 miles off the coast of Florida and 50 from Cuba. With a population nearing 400,000, the majority resides in the capital of Nassau, which lies on New Providence Island.

An estimated 30 Bahamians played in the Minor Leagues from the 1950s to '80s. Infielder Andre Rodgers was the first to reach The Show, appearing in 854 games in parts of 11 seasons with the Giants, Cubs and Pirates from 1957-67. Wil Culmer was the last Bahamian to play in the Majors (1983) until Richardson's debut in 2011. Interest waned as other sports like soccer, basketball and track and field grew in popularity and Bahamians achieved success.

On the global scale, 162 Bahamians have competed at the Summer Olympics and have won 14 total medals (six gold, two silver, six bronze) since the Melbourne Games in 1956. All but two have come from track and field. Chris Brown, the country's all-time winningest Olympian, won four medals in the 4x400 meter relay. At the 2000 Sydney Games, the Bahamas became the smallest nation to win an Olympic gold medal in a team event (women's 4x100m relay). Five Bahamians have played in the NBA, with Deandre Ayton -- who was drafted in 2018 -- the most recent. Three have appeared in the NFL, and the Colts selected Mike Strachan in this year's draft.

According to Geron Sands, the director of baseball operations at the International Elite Sports Academy in Nassau, baseball is seen as a niche market. In high school, fast-pitch softball -- not baseball -- is played. Recruiting doesn't get as intense as other sports. Sands, for example, began coaching Chisholm at 10 when someone else passed the youngster on to him.

I feel like my 12-year-old class was probably the best Bahamas class I've ever seen.

Jazz Chisholm Jr.

Richardson, now 37, was first introduced to the sport at the same age. His best friend's family at the time had a farm, where they would spend the morning shoveling horse and cow manure off the field. His friend's father paid out of pocket to get them equipment, and they sold food on the side of the road to buy a pair of cleats. Richardson didn't start playing baseball full time until he was a junior in high school.

Not much changed years later across Chisholm's childhood. He remembers the trouble of finding cleats or baseball gloves. Despite that, his Freedom Farm Little League team in 2012 featured a pair of future MLB Pipeline top prospects in Lucius Fox (Royals) and Chavez Young (Blue Jays).

"Honestly, I feel like there's always been an interest for guys from the Bahamas. It was just that it was hard to show that we had the talent in the Bahamas because we didn't have the equipment and the fields and stuff," Chisholm said. "I can tell you there's a lot of guys in the Bahamas that have my talent. I'm not the only one in my class that has the talent that I had. All of us had the same training coming up, but when you get to that high school level, everybody goes to different schools and does different things. I feel like my 12-year-old class was probably the best Bahamas class I've ever seen."

During this era, Bahamians would go to high school in the United States and either get drafted or move on to college. As teenagers, Sands and Richardson left home to attend American Heritage in Delray Beach, Fla. Both went on to play at Palm Beach Community College before transferring to Vanderbilt and Nova Southeastern, respectively. Richardson would appear in 22 Major League games from 2011-14, while Sands got as far as independent ball. Chisholm, like his mentors, traveled to the U.S. for two years of high school before returning home. His cousin took the college route.

"It definitely was a sport that wasn't the most accessible because of funding, but personally, I was just very fortunate because there were a lot of people who invested in the community and wanted us to have these opportunities," Richardson said. "So we've been fortunate. I think you ask a lot of the guys as they've gotten older. They probably, in retrospect, recognize how much has been sacrificed to be able to have a conversation with you right now."

The changing tide

The 2010 Michael Jordan Celebrity Invitational Softball Challenge, which saw the likes of Derek Jeter, Wayne Gretzky and Mia Hamm participate, drew sports legends to the country. Richardson and Sands served as umpires at the event. Around that time, Richardson started networking, speaking with people in the industry about the potential of baseball in the Bahamas. He invited them to visit, emphasizing the athleticism they would find.

Three years later, the trio of Sands, Greg Burrows Jr. and Albert Cartwright decided to make Bahamian talent harder to ignore by opening Maximum Development Baseball Academy in Nassau. It was through this avenue that Dale Davis became the first signing in March 2015. Eighteen months after returning to the Bahamas, Chisholm inked a $200,000 bonus with the D-backs on July 2, 2015. Fox, the headliner of that international signing class, agreed to a $6 million deal with the Giants. Larry Alcime (Pirates) also was part of that second group.

If I could help one out of 10, that's helping somebody, and giving them hope. Show them that Jazz, his family's from the inner city as well. 'Jazz made it, so why can't you make it?'

Geron Sands

No longer did players have to leave their homes to be found. Now the scouts were coming to them.

"It's kind of changed, and I'm glad I was one of the guys that helped change that culture," Chisholm said. "It was always something in the Bahamas if you didn't go to America to go to high school and play baseball, you weren't going to make it. … After I signed my contract, there were just more scouts going down to the Bahamas to watch the guys play, so they don't have to go away from their family and be living on their own from 12, 13 years old."

But it wasn't until Richardson scored the walk-off run for the Yankees in Jeter's final at-bat at Yankee Stadium on Sept. 25, 2014, that baseball's popularity reached a new height in the country. That pivotal moment showed Bahamian boys like Chisholm that anything was possible. No dream was too big, and all that hard work could pay off.

Four years later, Sands and Cartwright partnered up at International Elite Sports Academy. Cartwright, the director of player development, spent time in both the Astros' and Phillies' organizations before finishing up his pro career in independent ball. Bahamian ballplayers are part of a small, tight-knit brotherhood, with Sands and Cartwright considered the father figures.

"The whole idea for me with the academy and everything was to prove to the world that Bahamians can play baseball, that we can do it just like anybody else," Sands said. "Next thing is just to help kids receive education through the sport of baseball, become impactful to their communities, to be productive citizens of the Bahamas once they're done. So that is the whole gist of it, and I really wanted to help the inner-city kids. If I could help one out of 10, that's helping somebody, and giving them hope. Show them that Jazz, his family's from the inner city as well. 'Jazz made it, so why can't you make it?'"

Developing the talent

Unlike their counterparts in the Americas, Bahamians start playing later -- usually around the age of 10 or 11 but sometimes as old as 14. Since Bahamians are more raw, scouts give them more time to train. Projecting can be tougher without years of ballplaying experience. The market certainly isn't as fast as it is for Dominicans and Venezuelans, where players often sign when they are 16.

"We give a little space to the Bahamians for them to develop," Marlins international scouting director Fernando Seguignol said. "You're talking about two, three months, go back down there, you see something different, you just keep adding to the report. Next thing you know we're like, 'All right, we've come to the decision,' where it's done with the executive group and we make a decision as a team to go out and sign these kids."

A lot of people don't believe in Bahamian baseball, but we see the talent that we have. And it's slowly coming up. Our job is to prove that this is what we bring to the table.

Marlins prospect Ian Lewis

That's where Sands and Cartwright come in, preparing aspiring ballplayers for the possibility of a career in the sport. Currently, 24 kids are participating in the I-Elite program on a full-time basis. Another 20 are part time. The youngest are between 11 and 12 years old, with the oldest 16. There is no cost to attend the academy besides a regular school fee. Sands' wife, Danielle, serves as the administrator, and the principal has 40-plus years in education.

There is homeschooling in the morning, and then, for six to seven hours a day, six days a week, the future of Bahamian baseball works on its craft. Training includes a "Bahamian flair" -- as Sands puts it -- meaning workouts on the field, at the gym or at the beach. Yoga, water aerobics and runs up the hill at St. Anne's School or along the sand at Montagu Beach are fair game. The academy tries to scrimmage on the weekend, even if it's with the two local leagues. Once a month, it travels to the island of Grand Bahama, which is 133 miles away, to face other kids in tournaments.

At least 25 Major League organizations visit when the academy hosts a major showcase in October and January. The facilities aren't up to the standard of more developed baseball regions, and equipment is always needed -- from baseballs and bats to fencing. Clay must be imported for Pinewood Field, the only standard-sized field in Nassau. Still, that doesn't deter the athletes. Sands attributes the defensive prowess of Bahamians to the field conditions, where hops bouncing any which way keep them on their toes.

A former shortstop, Sands has trained the kids to play his position or center field. Pitching hasn't caught on as much. In fact, right-hander Tahnaj Thomas, the Pirates' seventh-ranked prospect, is a converted infielder.

Marlins Minor Leaguer Ian Lewis is part of the new generation that is discovering baseball at an earlier age. He recalls taking a walk with his mother as a 4-year-old and ending up on a field down the street from his house. From then on, he was hooked, catching highlights on TV and playing tee ball.

"They always told us that it's going to be a competition -- but not really a competition to play against each other, but to bring out the best you can possibly bring out," Lewis said about the mentality that was instilled in him during his six years at the academy. "A lot of people don't believe in Bahamian baseball, but we see the talent that we have. And it's slowly coming up. Our job is to prove that this is what we bring to the table.”

There would have been probably three [Giancarlo] Stantons in baseball, like the kids from the Bahamas that I've seen.

Jazz Chisholm Jr.

A new frontier

The expectation is there won't be as much time in between Chisholm's debut and the next Bahamian to reach The Show. The D-backs, who signed Chisholm before dealing him to the Marlins in 2019, have MLB Pipeline's No. 44 overall prospect Kristian Robinson in their system. Several clubs have multiple prospects from the Bahamas, including the Angels with D’Shawn Knowles (No. 8) and Trent Deveaux (No. 20). Other organizations like the Padres recently signed their first (Evan Sweeting).

"Everything was kind of tough coming up, and I saw a lot of talented kids," the 23-year-old Chisholm said. “There would have been probably three [Giancarlo] Stantons in baseball, like the kids from the Bahamas that I've seen."

Seguignol didn't know about the growing hotbed until taking over the role for the organization in 2018. Once he saw the prospective talent, he started sending cross checkers. The Marlins see the Caribbean as a region of geographical importance based on proximity and opportunity. They are one of 15 Major League teams that have bought into the Bahamas. Though there isn't a designated scout there, it's only an hour away by plane. Seguignol often boards the first flight in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., then spends the day checking out both academies before hopping on the final flight home.

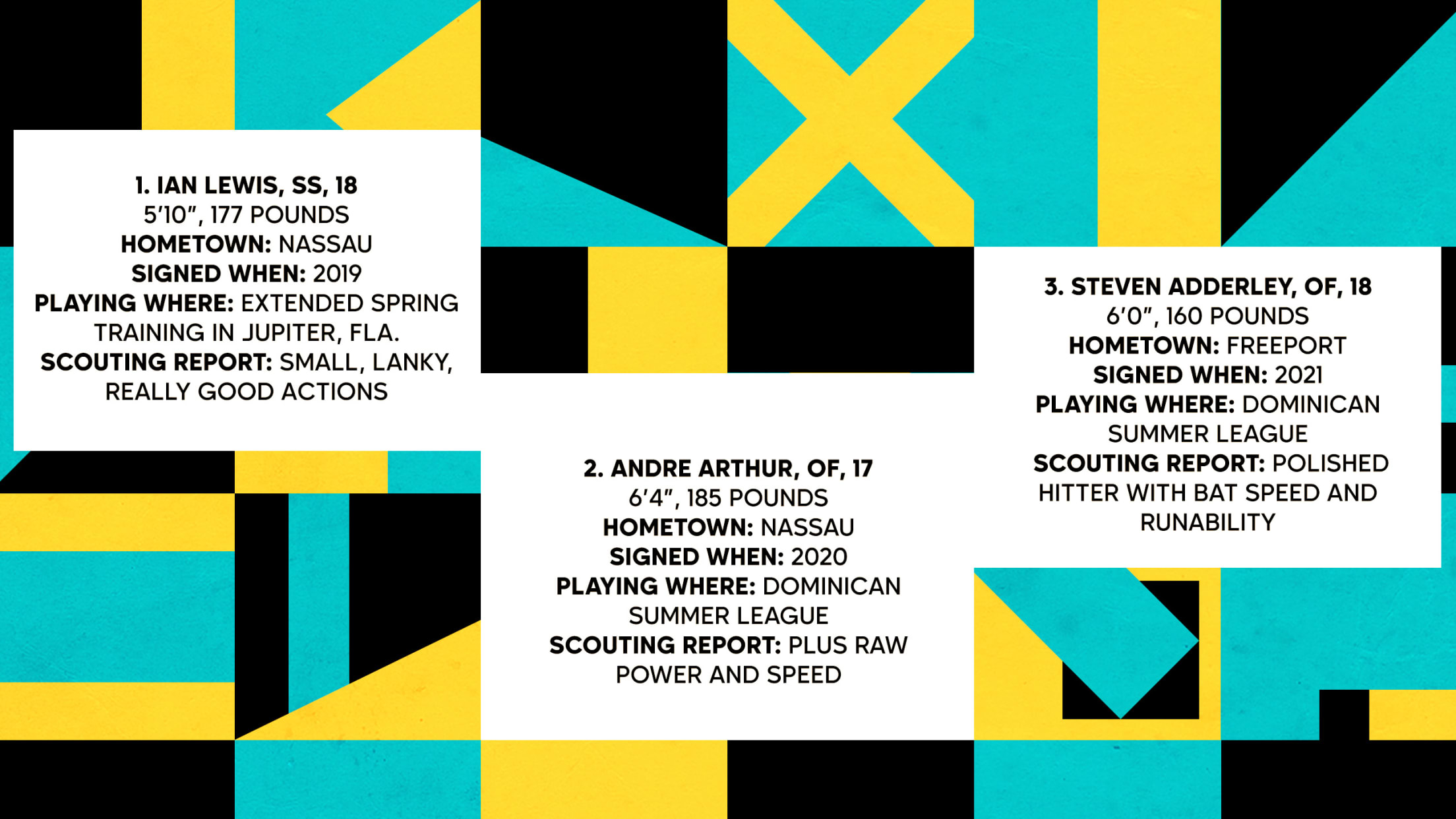

Chisholm is one of four Bahamians with the Marlins. The other three -- Lewis, Andre Arthur and Steven Adderley -- have been signed within the past three years and took part in Sands' and Cartwright's academy.

"The Bahamians are natural athletes," Seguignol said. "You see these guys, just lean, athletic. They're built to do so many things in sports, generally, not only baseball. I'm not saying baseball is the top; it's making that run for the money now."

While Chisholm didn't necessarily root for the Marlins growing up, he was a fan of the 2008 club that boasted sluggers Dan Uggla and Hanley Ramirez. Lewis signed with Miami because of how close it is to home, the city's culture and the feeling of support within the organization. He has noticed more Bahamians watching the ballclub to see how one of their own performs, witnessing the buzz firsthand from the stands at loanDepot park during Chisholm's at-bats. The Marlins recently announced they will celebrate Bahamian heritage on June 12 as one of their 11 heritage games this season.

"We are the window of the Americas," Seguignol said. "It's a nice spot for these guys to want to sign with the Marlins, and we're interested in building a relationship and branding, getting that out there. It's just a perfect match for us to be in at least the conversation when we're talking about top players down there."

From 1997-2012, there was no more than one Bahamian in professional baseball. In 2013, there were two. The biggest jump came in 2014-15, going from five to 11.

It has been a steady climb that coincides with the academies developing talent, leading to this season. There are now 21 Bahamians playing in the Minor Leagues this year, with Chisholm in the Majors and a handful of others in college and independent ball.

The Bahamas is no longer a secret.

I promise you, in three to five years we're going to have a ton of guys in the big leagues. Jazz is good, but we have guys just like that coming, and every year it's getting better and better and better.

Geron Sands

The older generations want to pay it forward, providing opportunities and awareness to those who follow in their footsteps. Richardson returns home when the season is over, as his Project Limestone organization emphasizes not just development in baseball but also in science, technology, engineering and math. Fox and Frontier League player Todd Isaacs organized the annual Don't Blink Home Run Derby in Paradise that takes place on the water. Chisholm, Lewis, Marlins teammates Lewis Brinson and Monte Harrison as well as Blue Jays shortstop Bo Bichette have competed in it. Sands and Cartwright throw BP. It's a team effort to put the picturesque event together.

Chisholm has contributed in various other ways, from visiting schools to speak to the kids to taking grounders alongside I-Elite's participants. So has Phillies shortstop Didi Gregorius, who stopped by a few years ago. Though he was raised in Curaçao, Gregorius shares the same agent as a few of the Bahamians. I-Elite plans to start an academy in Freeport come September, but for now, it relocates 30 kids from Grand Bahama to Nassau. And while the Andre Rodgers National Stadium was demolished in 2006, a baseball complex has been under construction.

"I promise you, in three to five years we're going to have a ton of guys in the big leagues," Sands said. "Jazz is good, but we have guys just like that coming, and every year it's getting better and better and better. I'm excited for what's coming. I'm glad Jazz started it off pretty well. I told him to keep it going, pass the baton to somebody else."