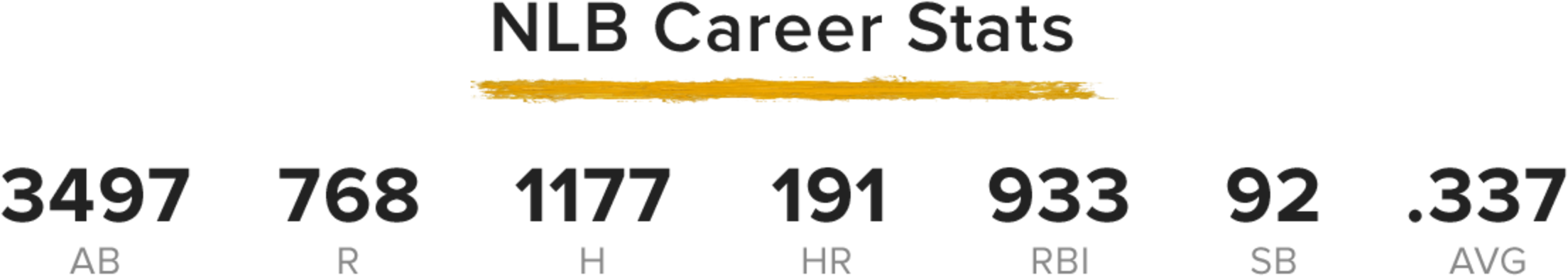

Records of Negro Leagues Baseball statistics are incomplete. The above was compiled using various sources including the Negro Leagues Database at seamheads.com after consultation with John Thorn, the Official Historian for MLB, and other Negro Leagues experts. In December 2020, MLB bestowed Major League status on seven professional Negro Leagues that operated from 1920-48. MLB and the Elias Sports Bureau are in the process of determining how this will affect official MLB records and statistics.

'Mule' a quiet Negro Leagues legend

By: Jake Rill | @JakeDRill

“Kick, Mule, Kick! Kick, Mule, Kick!”

When George “Mule” Suttles stepped up to the plate throughout his 22-year career in the Negro Leagues, fans in attendance knew they might be in store for something special. That’s why they chanted the stocky first baseman’s nickname, hoping to see him show off his powerful swing.

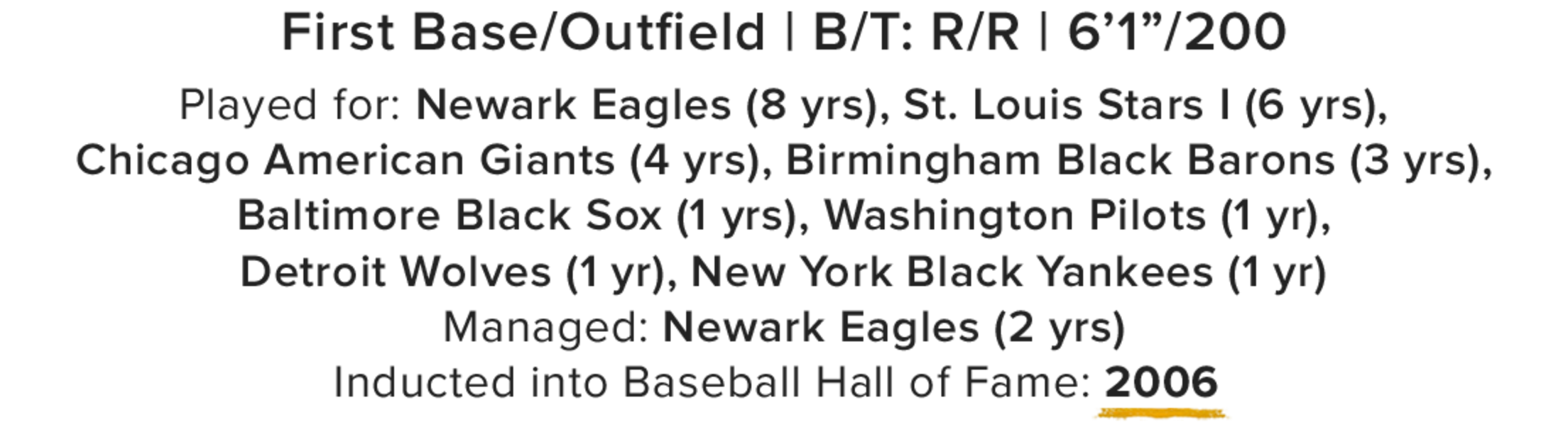

And quite often, Suttles did. Not only in the form of home runs, but with long knocks that resulted in doubles and triples. A .328 career hitter, Suttles did much more than swat nearly 200 homers across his time in the Negro National League and the East-West League – he also collected 232 doubles, 82 triples and nearly 1,000 RBIs.

Yet Suttles doesn’t typically get the same attention received by other former Negro Leagues stars, and he didn’t even get inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until 2006, 40 years after his death.

“We always wondered why Uncle George was never mentioned,” Merriett Burley, Suttles’ niece, said at the Hall of Fame ceremony in '06. “They always mentioned Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, but they never mentioned Uncle George. We’re now saying he’s getting his just rewards.”

Why did it take so long? Not because of his play, but perhaps due to his small upbringing and reserved demeanor, because his stats always appeared worthy of inclusion in the Hall of Fame.

Suttles was born on March 31, 1901, in Blocton, Ala., a coal-mining town that no longer exists. He was the son of a coal miner, and he also worked in the mines when his family moved to Birmingham during his teenage years.

However, it didn’t take long for Suttles to find baseball. He began playing for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League as a 22-year-old in 1923.

Leslie Heaphy, a member of the Society for American Baseball Research board and a baseball historian, has done extensive research into the Negro Leagues, including Suttles’ unheralded career. She notes that Suttles is often described as “very quiet,” but “well liked” in many accounts from his time.

It just didn’t lead to the type of attention that Suttles’ power and pure hitting ability appeared to deserve, even when he was still playing.

“You’ll be reading an article, and it tells you then at the end of it, ‘Oh, by the way’ – almost exactly that – ‘They won because Suttles hit two home runs.’ But that isn’t the headline,” Heaphy said. “So it’s like, ‘Oh, wow,’ you could easily miss that.”

Suttles was a popular player, though. His “Mule” nickname appeared in newspaper articles from early in his career, according to Heaphy. And while it’s unclear exactly when or how the nickname was coined, it stuck (even appearing on his Hall of Fame plaque at Cooperstown) and led to great fan support.

Suttles began his career with three seasons playing for the Black Barons, but he later had stints with the St. Louis Stars (1926-31), Chicago American Giants (1929, 1933-35), Baltimore Black Sox (1930), Detroit Wolves (1932) and the Newark Eagles (1936-40, 1942-44). And he racked up his impressive hitting stats while swinging a heavy, 50-ounce bat.

Several of Suttles’ most noteworthy moments came while playing in the East-West All-Star Game, an annual event that was held for the best players in the Negro Leagues from 1933-62, which he participated in five times. He hit the first home run in the game’s history, slugging the lone homer in the 1933 contest to help the West win, 11-7.

In 1935, Suttles hit another East-West All-Star Game home run – a two-out, three-run, walk-off homer that lifted the West to an 11-8 victory in the 11th inning.

Because of his power and heavyset frame, it’s easy to classify Suttles as a Babe Ruth-type player. But those aren’t the only reasons that Suttles has drawn comparisons to Ruth.

“He was a power hitter, but he delivered. He wasn’t a Dave Kingman, who either struck out or hit a home run and nothing in between,” Heaphy said. “He was not the .230 hitter that Kingman was. And yet, he probably had power like him. So, the comparison to, in some ways, sort of the way you think about Babe Ruth, because that was true of him, too – he was a very solid hitter, but he was also the power hitter, a big home run hitter.”

Suttles spent two years as the manager of the Newark Eagles, wrapping up his baseball career in 1944, three years before Jackie Robinson became the first Black player to appear in an MLB game. So Suttles never got a chance to play in that league, which could have drawn more attention to his game.

After Suttles retired, the Newark Eagles went on to win the Negro World Series in 1946, another case of him just missing out on an opportunity to appear on a big stage that could have given him similar attention to well-known players of the time, such as Gibson and Paige.

“I can’t fathom why he didn’t get the publicity they got,” said former Negro Leagues pitcher Squire Moore, per Suttles’ Baseball Hall of Fame profile. “He was a laid-back person. He didn’t do much talking. He wasn’t the boastful type. Sometimes the better players get overlooked.”

Perhaps none more so than “Mule,” who still went down in baseball’s history books not just for being a slugger, but for being one of the best all-around hitters of the Negro Leagues era. And certainly one of the most popular.