Why this submariner could reach great heights

The season was five months old and the dog days had set in by the night of Aug. 27, 2019. A full slate of Tuesday night games was humming along. Pitchers across the Major Leagues rode the top of the zone with blazing fastballs. Nasty curveballs and sliders were cut for GIFs and retweeted from Pitching Ninja’s Twitter account. It was another world’s fair night in baseball, featuring the latest and greatest in velocity and spin.

And then a 28-year-old rookie took the mound in San Francisco. He stood 6-foot-5 and looked a little lankier than your standard big league pitcher. Otherwise, nothing seemed amiss. But then this rookie did something only a few prospect-minded Giants fans could have anticipated. Instead of rearing back for gas, he bowed at the waist. Then he whipped his arm below his torso, with his fingers nearly scraping the dirt, like a boy skipping a stone.

In tumbled Tyler Rogers’ first big league pitch: An 83-mph fastball. Strike one. His first pitch in The Show was unlike any of the nearly 600,000 pitches tracked before his arrival last year -- from the way he threw it to the way it rolled in. Adam Jones, the batter at the plate, had seen roughly 25,000 pitches over his 14-year career. Maybe a handful of them had ever looked like this.

Rogers’ next pitch was a bold carbon-copy -- down-and-in, low 80s and full of risk -- but Jones tapped it harmlessly to the shortstop. An easy 6-3 was in the books.

“That is as low as you go,” said Giants broadcaster Mike Krukow, and he was right -- Major League Baseball hasn’t seen a throwing motion this extreme in years.

But Rogers could also be more than a novelty; he might be the most dominant reliever you haven’t heard of. In his first five weeks as a big leaguer, opponents mustered two earned runs and hit .185 without a single home run. Rogers’ 70% ground-ball rate, the Majors’ third-highest, meant hardly anyone had the chance to go deep (you can’t slug on the ground), and not one of the batted balls hit against him was even barreled, or struck with the kind of power and trajectory that usually produces an extra-base hit.

Rogers’ 1.02 ERA was the second-lowest of anyone who threw at least 15 innings in the Majors last year, and he achieved it with a fastball that averaged just 82.4 mph -- the third-slowest of any pitcher tracked by Statcast since 2015.

“It takes a crazy guy to throw 83-mph fastballs to big league hitters,” Rogers admits, but that’s exactly what he plans to do.

Actually, Rogers doesn’t have much of a choice -- 83 is about as hard as one can possibly throw from their shoes, as he does. The choice to do that, and stick with it for years, as Rogers has, is even bolder. Beyond trying to be a trusted reliever for the Giants when baseball returns this month, Rogers is attempting to do something only a handful of men have ever successfully achieved in the Major Leagues: He’s trying to be the next full-time submarine pitcher.

---

Every kid grows up wanting to be unique. But as rare as throwing underhand is, almost no young pitcher chooses that the first time they pick up a ball.

A submariner like Rogers hasn’t fit into the Major League mold since the 1870s, when every pitcher threw underhand and acted as a batter’s ally. A pitcher’s job was to toss the ball and initiate action, not try to strike out the hitter. The famous first rules of baseball, drawn up by New York’s Knickerbocker Club in 1845, spelled out the relationship: “The ball must be pitched, not thrown, for the bat.”

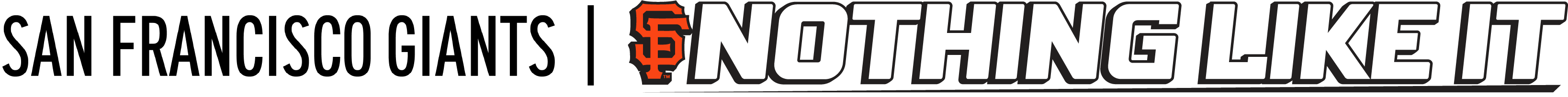

But competitors were already itching to break free of that mold. In the late 1850s, 17-year-old Jim Creighton of the Brooklyn Niagaras added an undetectable snap to his wrist as he bowled the baseball, thus adding spin and movement that made his pitches “fairly unhittable.” The Star of Brooklyn club quickly offered Creighton a lucrative salary, making him baseball’s first professional player, and observers feared the purity of the game was already slipping away. After Creighton, pitchers immediately began pushing the envelope with how high they could raise their arms. The National League finally relaxed all restrictions on pitching motions in 1884 and saw an immediate result: Providence’s Charlie Sweeney, freed up by the rule change, struck out 19 hitters in a game.

Most pitchers, from youth sandlots to the professional ranks, never looked back, taking advantage of their overhand freedom to add velocity and spin to their repertoires. Baseball now centered around the pitcher vs. batter battle and, with the exception of men like Iron Joe McGinnity (who developed an underhand pitch named “Old Sal” as change-of-pace), Jack Warhop (supplier of Babe Ruth’s first pair of home runs) and Carl Mays (forever known as the man who killed Ray Chapman with a pitch Chapman never saw coming), few practitioners stuck with the underhand throw.

Instead, the Majors have averaged maybe two to three submariners per decade for more than a century now, and almost all of them got there by necessity: Either they adapted and tried something completely new, or they risked being left behind. Elden Auker, who started for the Tigers in the 1934 and '35 World Series, switched to underhand after he separated his shoulder playing college football. Ted Abernathy came back after three years out of the game with an underhand motion and averaged 91 innings a season for the next decade.

Abernathy directly inspired Kent Tekulve, the dean of submariners. Stalled as a Double-A pitcher at the time, Tekulve thought back to when he grew up watching Abernathy pitch for his hometown Reds. Goofing around with a teammate, Tekulve channeled his boyhood idol and tried a sidearm sinker. The ball bottomed out so much that his teammate missed it completely.

“I thought, ‘I’m not the smartest guy in the world, but I think this is pretty good,’” Tekulve recalls. “I literally had that pitch from the very first day.”

Tekulve went on to notch three saves for Pittsburgh in the 1979 World Series, and got a call from Royals manager Jim Frey the next spring. Kansas City had a 27-year-old pitcher who had thrown so many innings (194) as a college senior that his arm slot had dropped to the side -- and stayed there. Frey looked at this funky pitcher with a funky name -- Dan Quisenberry -- and wondered if he might have the next Tekulve on his hands.

Come to Royals camp, he asked Tekulve, and mold this Quisenberry into a submariner like yourself. Tek obliged, but soon discovered he didn’t need to do much.

“My only request was that the pitching coach be there with us to hear what I said,” says Tekulve. “I just told Quiz, ‘What you’re doing is right.’ And I don’t know if he’d ever run into anyone to tell him that, because nobody else he’d met had done it.”

Quisenberry would soon call Tekulve “Dad,” even sending him cards on Father’s Day. Quiz hardly ever threw faster than 84 mph, but with a career rate of just 3.3 strikeouts per nine innings, he still wound up being the American League’s most dominant closer of the 1980s. In fact, Quisenberry’s era-adjusted 146 ERA+ remains one of the 10 best marks in history.

When the best submariners have gotten there, they’ve stuck. Tekulve didn’t debut until he was 27, but he retired with the second-most appearances (1,050) in MLB history. Quisenberry came up at 26 and pitched across the entire 1980s (career ERA: 2.76). At 28, A’s submariner Brad Ziegler broke a Major League record with 39 consecutive scoreless innings to begin his career, kicking off more than a decade as a late-innings option. Chad Bradford, the lowest submariner of them all, was stuck with the White Sox Triple-A club and months away from pitching in Japan when Billy Beane traded for him. He became a bullpen staple for both the Moneyball A’s and Joe Maddon’s Rays.

These stories have given submariners a rubber-armed reputation -- but they have to convince people to let them play first.

“I pitched 15 years,” says Tekulve, “and for most of them people didn’t look at me believing it would work.”

---

Rogers didn’t just pick up a ball and say, "I want to throw underhand," either. His submarine life began with a frank conversation with Chris Finnegan, the head baseball coach at tiny Garden City Community College in western Kansas. Rogers had come to Garden City to study fire science and then become one of America’s only fifth-generation firefighters back in his hometown of Littleton, Colo. Rogers’ baseball scholarship made that education free, but his 86-mph fastball wasn’t getting JUCO hitters out.

Finnegan gave Rogers a choice: He could be another righty who didn’t throw hard enough, or he could be Garden City’s next closer. But to do the latter, he’d have to try something wacky. Bend down and pretend to be a shortstop, Finnegan told Rogers, and fling the ball sidearm like you were throwing to first base. Funny as the suggestion was, it felt natural for Rogers. Easier than pitching overhand.

Rogers knew first-hand what a Major League throwing motion looked like, and he knew he didn’t have it. His identical twin brother, Taylor, got the longer straw at birth, given the ability not only to throw much harder (like, mid-90s hard) but also to do so left-handed. Taylor got the recruitment letters and pitched for the University of Kentucky. Now, he’s the Minnesota Twins’ bullpen ace.

How one twin brother got the pitching tools scouts drool over while the other was left with the more ordinary skills is something both of the Rogers brothers can only guess at. Whatever happened, it left one Rogers brother to improvise.

“He got blessed with the left hand and the velocity,” Tyler jokes about Taylor. “I had to figure something out.”

So here, at Finnegan’s suggestion, was a project. The big leagues were still far from Rogers’ mind, but this was something he could set his mind to while studying. He was hooked.

“In baseball, you’ve got to find a way to separate yourself,” says Rogers. “I knew this would be my separator.”

This project meant Rogers essentially started from scratch, shadowing a side-arming teammate named Reese McGraw and inching his way back up from a bucket of balls and a net to the top of the pitcher’s mound. He was lucky to have Finnegan as an open-minded coach, but from there, Rogers, like nearly all submariners, was on his own. He looked for in-game videos, from the old-school Tekulves and Quisenberrys to the more modern drop-down guys like Ziegler and Darren O’Day, but their footage -- even in 2020 -- is still limited mostly to grainy YouTube videos. Rogers says his slider came a long away after he watched O’Day pitch on a restaurant TV.

Pitching coaches have a wealth of knowledge on body mechanics, but few of them know how it actually feels to pitch underhand. Take Tekulve’s first conversation with Claude Osteen -- the former All-Star pitcher-turned-Phillies pitching coach -- when Tekulve was traded to Philadelphia in 1985.

“He said, ‘I’m gonna tell you something: I do not have one idea about what you’re doing or how you’re doing it -- I’m clueless,’” Tekulve recalls. “This was the guy running the pitching staff!”

Not much had changed 25 years later. A young submariner like Rogers was still left mostly to his own devices. Countless days of trial and error. Feel and intuition.

“The biggest thing with me is the feel aspect more than anything else,” he says. “It’s all been about experimentation and learning the delivery for myself.”

---

Rogers developed a feel for that underhand thing. He was an out-getting machine by his sophomore year, and soon Austin Peay State University came calling. Two years, 79 Division I appearances and a sterling 1.98 ERA later, it became clear that Rogers’ firefighting dreams would temporarily take a backseat. The Giants picked Rogers in the 10th round of the 2013 Draft, and across seven long years in the Minors his career ERA held at 2.52, better than all but eight other Minor League pitchers (minimum 300 innings pitched) from 2013-19. But the biggest hurdle of all still stood in his way: an opportunity.

“I think I was more frustrated than he was, to be honest with you,” says his brother Taylor. “Just because I played catch with him and knew how good his stuff was and how good it played, and he was just showing it year after year. I just wanted him to have his shot.”

The man who can identify most with Rogers’ career arc might be Bradford, the knuckle-scraping reliever. Watch Bradford and Rogers side by side and they’re basically kindred spirits, each testing how perilously close to the earth they can go. Bradford’s hand bounced off the dirt several times in his career, while Rogers says he’s avoided that -- so far.

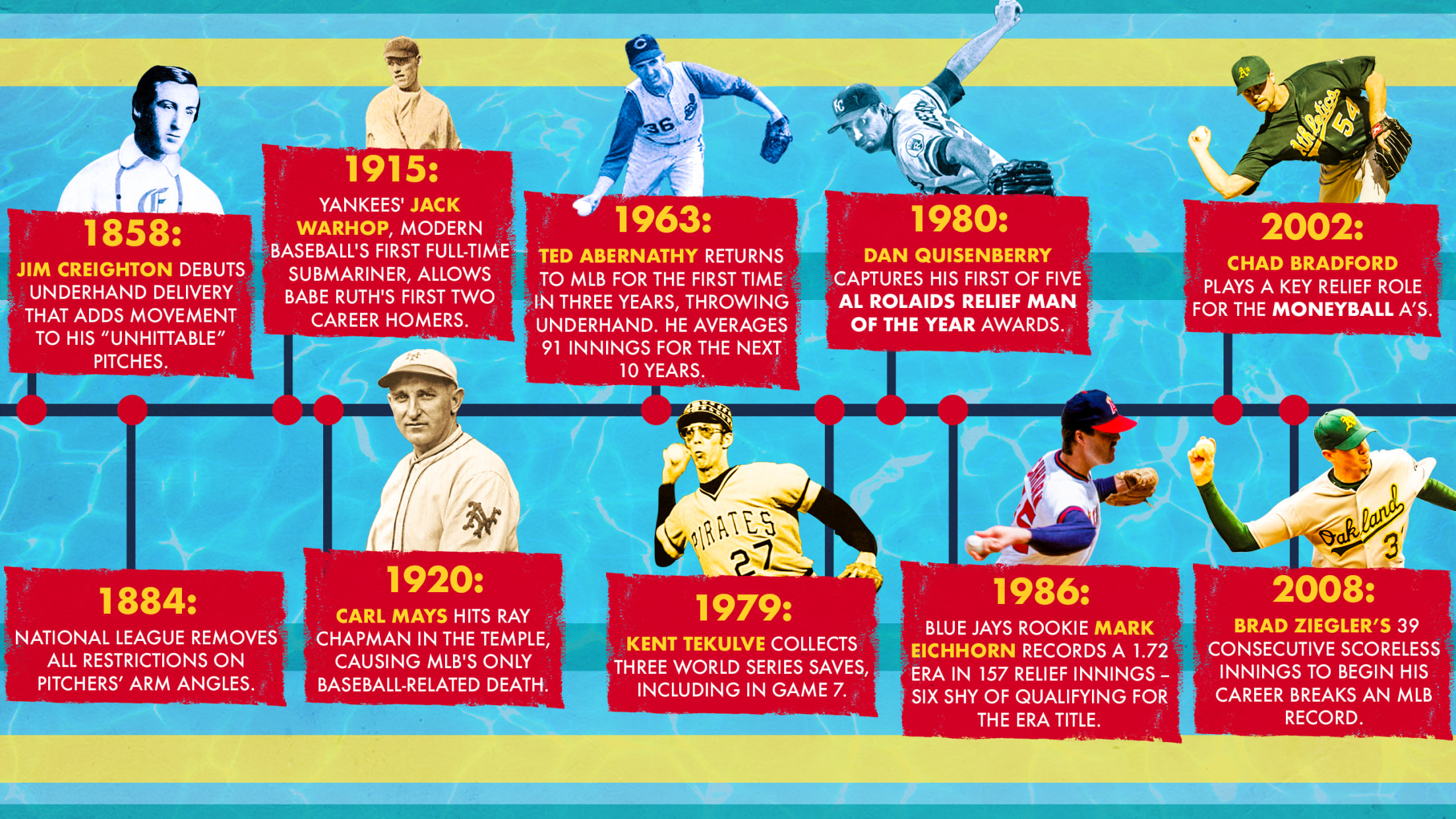

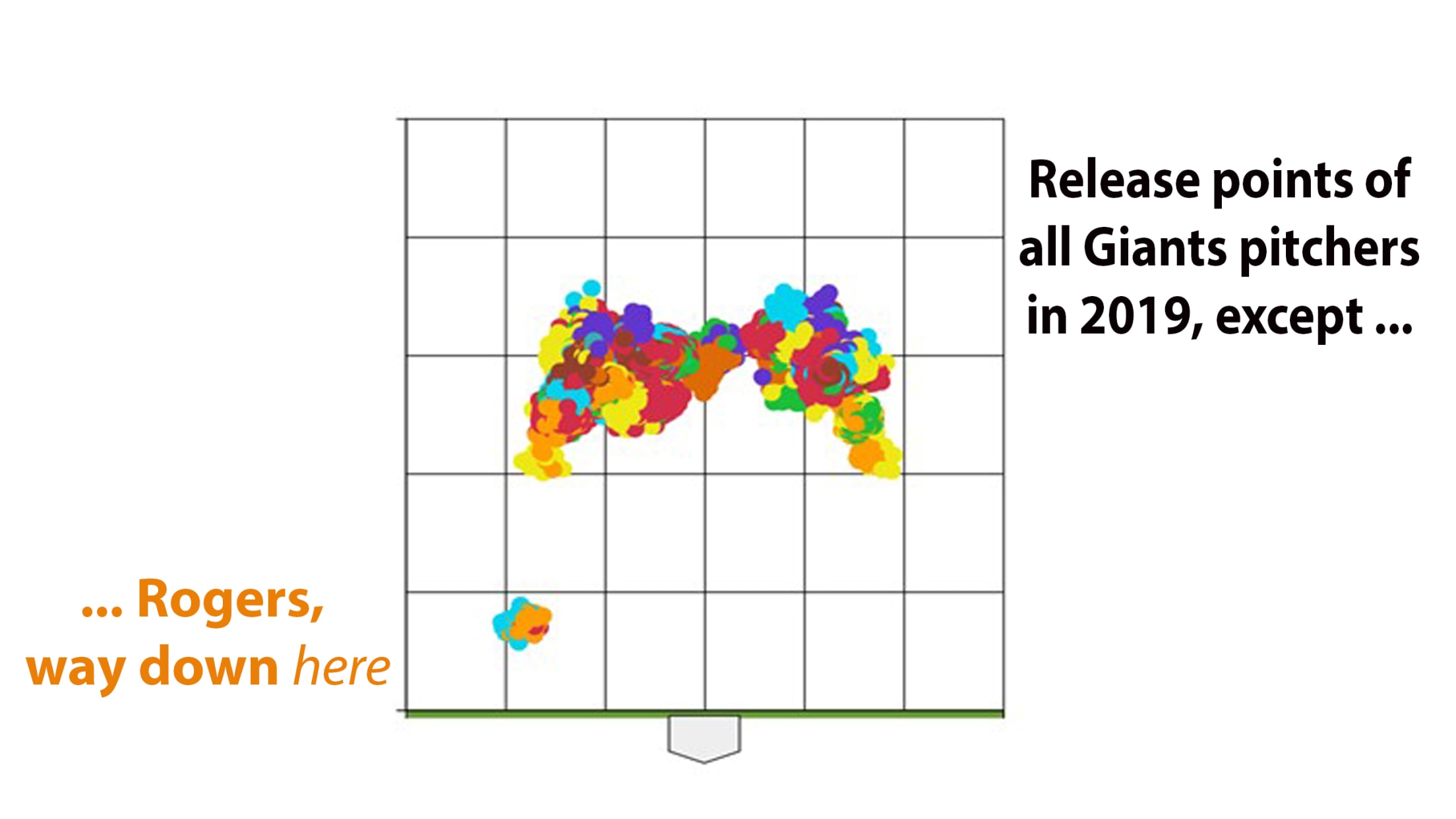

In fact, Bradford is perhaps the only man who has even come close to Rogers’ release point off a big league mound. Since Statcast’s pitch-tracking cameras turned on in 2015, no one has averaged a lower release point than Rogers, at one foot off the ground. Other famous submariners, from Quisenberry and Tekulve to more modern names like Byung-Hyun Kim, Joe Smith, O’Day and Ziegler, certainly crouched and bent over at the waist, but none of them actually released the ball much below their hips, let alone their knees.

Comb through the technicolor VHS tapes, the archival videos and black-and-white photographs, and Bradford appears to be Rogers’ one true shoelace companion. When told he could be tied for the lowest thrower of all time, Rogers said he had no idea he was making history. Funny enough, neither he nor Bradford set out to throw the ball that way.

“I see pictures of myself, and I really don’t feel like I’m throwing that low,” Rogers says. “One day I went to my coach in High A and asked, ‘Did I really get lower throughout the year?’ He said, ‘Yeah, but you were getting results, so I didn’t want to say anything.’”

Bradford also knows what it’s like to wait.

“If a team knows a pitcher throws 98 for a fact, they trust that,” says Bradford, now coaching high schoolers in his native Mississippi, “but if they go see someone pitch with a funky angle, they start to wonder, ‘Is that going to play out at the higher levels? Can he get the outs?’ Those are unknowns. They don’t trust that as much.”

Rogers watched the Giants call up harder-throwing prospects for several Septembers in a row. When the days rolled by again last summer, Rogers started thinking about Plan B. On Aug. 26, he bought a textbook and looked at dates for upcoming firefighting tests. He’d also bought an engagement ring for his girlfriend, Jennifer, figuring he’d propose after the Minor League season ended on Sept. 4. Then, on the very next morning, the Giants called: Pack your bags for San Francisco. The time had finally come -- and Tyler and Jennifer were engaged later that week.

Now Rogers wants to be that same rubber arm, like the submariners before him. His new manager, Gabe Kapler, has raved about Rogers since the Giants’ first Spring Training camp opened months ago. In a radio interview earlier this month, Kapler hinted that Rogers could even be the team’s closer.

“[Rogers has] got the ability to go through left-handed and right-handed hitters, induce ground balls and get uncomfortable swings,” said Kapler. “There’s no real stretch in anybody’s lineup that would potentially be overwhelming for Rog. He’s a good candidate.”

For Rogers himself, the answer is simple: He’s hoping to be the guy Kapler relies on to put out a fire.

“I want them to know that I’m available for any inning on any day,” he says. “I think I can be that guy that pitches every day.”

But there are reasons why Kapler believes Rogers could be more than an innings-eater. Before he spoke for this story, Tekulve studied tape of Rogers and says his lengthy arm is the ideal lever to put torque on his sinker -- the bread-and-butter pitch of every submariner. Rogers says the vicious drop on that pitch is his self-described “radar gun,” more important than speed in letting him know if his stuff is right. That sinker racks up the majority of all those ground balls.

But Rogers’ showstopper pitch -- and perhaps his true difference-maker -- is his slider; a UFO-frisbee hybrid “riseball” that seemingly never stops climbing. After Rogers whips the pitch from a foot above the ground, it can wind up at a lefty hitter’s eyeballs, three to four feet above home plate. Thus, that slider has the potential to get up into a left-hander’s kitchen and neutralize the opposite-side matchup that typically gives a right-handed submariner fits.

Rogers had the sinker and the slider clicking in Spring Training, frustrating hitters to where even a foul ball was an accomplishment.

Rogers has waited years to unleash these pitches on big leaguers -- the pitches he built from scratch in Kansas, and the pitches he succeeded with for years in places like Salem, Richmond and Sacramento. The coronavirus pandemic meant he and the rest of the baseball world had to wait a little longer, but when the game finally does return, Rogers, armed with the confidence of last summer’s brilliant cup of coffee, is eager to prove that submariners can still hack it in 2020.

“Last year validated what I always thought,” he says. “I could pitch at the big league level.”