Was Gwynn's quest MLB's last real run at .400?

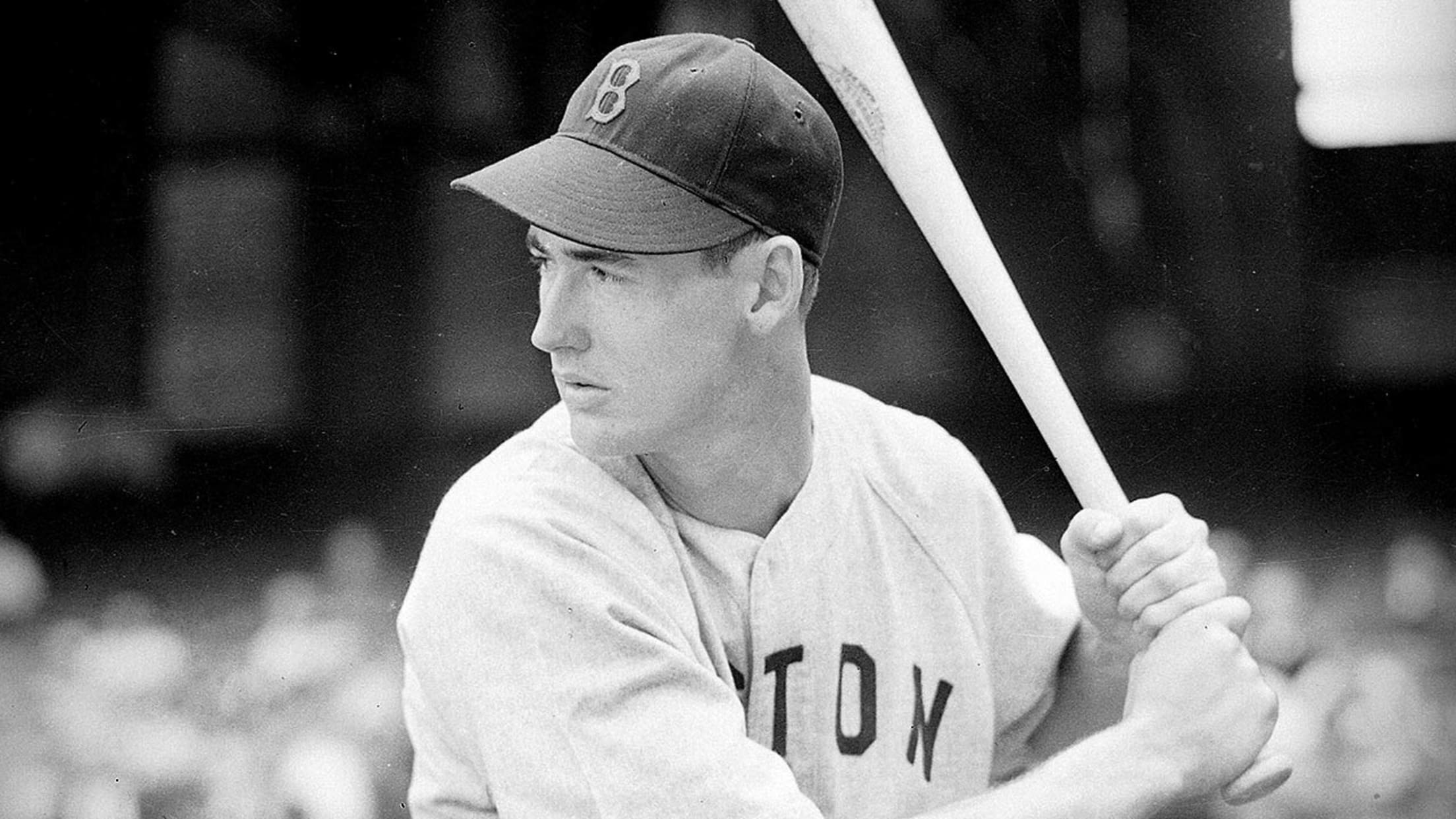

It's been more than 78 years since Ted Williams defied the odds. More than 78 years since Williams, a son of San Diego who grew into one of baseball’s greatest hitters, played two games on Sept. 28, 1941. Sitting on a .400 batting average entering the season’s final day, Williams played a doubleheader, knowing that it might jeopardize his place in history.

Surely, when Williams recorded his sixth and final hit that day, nobody believed he’d be the last .400 hitter. It had been done 28 times before, and it was bound to happen again.

This story has been updated from the original version that was published in August 2019. Saturday, May 9, 2020 would have been the late, great Tony Gwynn’s 60th birthday.

It still hasn't. Williams hit .388 in 1957. Rod Carew reached that same mark in 1977. George Brett got to .390 in 1980. In the meantime, the tone shifted -- from certainty, to belief, to doubt. In 2020, there's enough consensus that it's practically fact: Nobody will ever hit .400 again.

Twenty-six years ago, Gwynn found himself on a collision course with one of the sport's most sacred milestones. If he’d been sitting on .400 on the final day of the 1994 season, there’s little doubt he'd have chosen to play, too. Instead, Gwynn was hitting .394 on Aug. 11, and that's where the story abruptly ends.

This is that story. It's the story of Tony Gwynn and the summer of 1994. It's the story of an unreachable goal and a hitter who might have been good enough to reach it. It's the story of an athlete who worked tirelessly and a city who adored him for it.

It’s the story of baseball’s last chase for .400. And it’s a story where nobody enjoys the ending.

Chapter 1: Mr. Padre

April 4, 1994: Jack Murphy Stadium

Braves 4, Padres 1 (Box)

1st: Single to LF (off Greg Maddux)

3rd: Groundout to 3B (off Maddux)

5th: Bill Bean replaces Gwynn, playing RF batting 3rd

Batting average: .500

Gwynn’s 1994 season began in the most fitting way imaginable -- with a single through his favored “5.5 hole” against Maddux. A few innings later, Gwynn’s left knee barked, and he’d exit early before sitting out for a week. Gwynn had missed at least 27 games in each of the previous three seasons, and he battled balky knees for much of the second half of his career.

Perhaps the early rest did him good. Gwynn missed just one game over the remainder of the 1994 season, and he was healthy the rest of the way, ready to chase history.

Gwynn was San Diego's own. That -- as much as the .338 career average, the 3,141 career hits, the eight batting titles -- made him Tony Gwynn. There might not be an athlete more beloved by his city than Mr. Padre in San Diego.

"Of any star I'd ever seen," recalls longtime Padres broadcaster Ted Leitner, "he was the most accessible. He was closest to the fans."

Gwynn played baseball and basketball at San Diego State University, where he remains the school’s all-time assists leader. He was selected by the Padres in the third round of the 1981 Draft and led San Diego to its first National League pennant three years later. All the while, Gwynn racked up numbers that defy belief.

Nineteen straight seasons batting above .300. Seven seasons at .350 or better. A career .302 batting average with two strikes. More four-hit games than two-strikeout games.

“Nobody,” says longtime big league right-hander Orel Hershiser, “was like Tony Gwynn.”

Of any star I'd ever seen, he was the most accessible. He was closest to the fans.

Longtime Padres broadcaster Ted Leitner

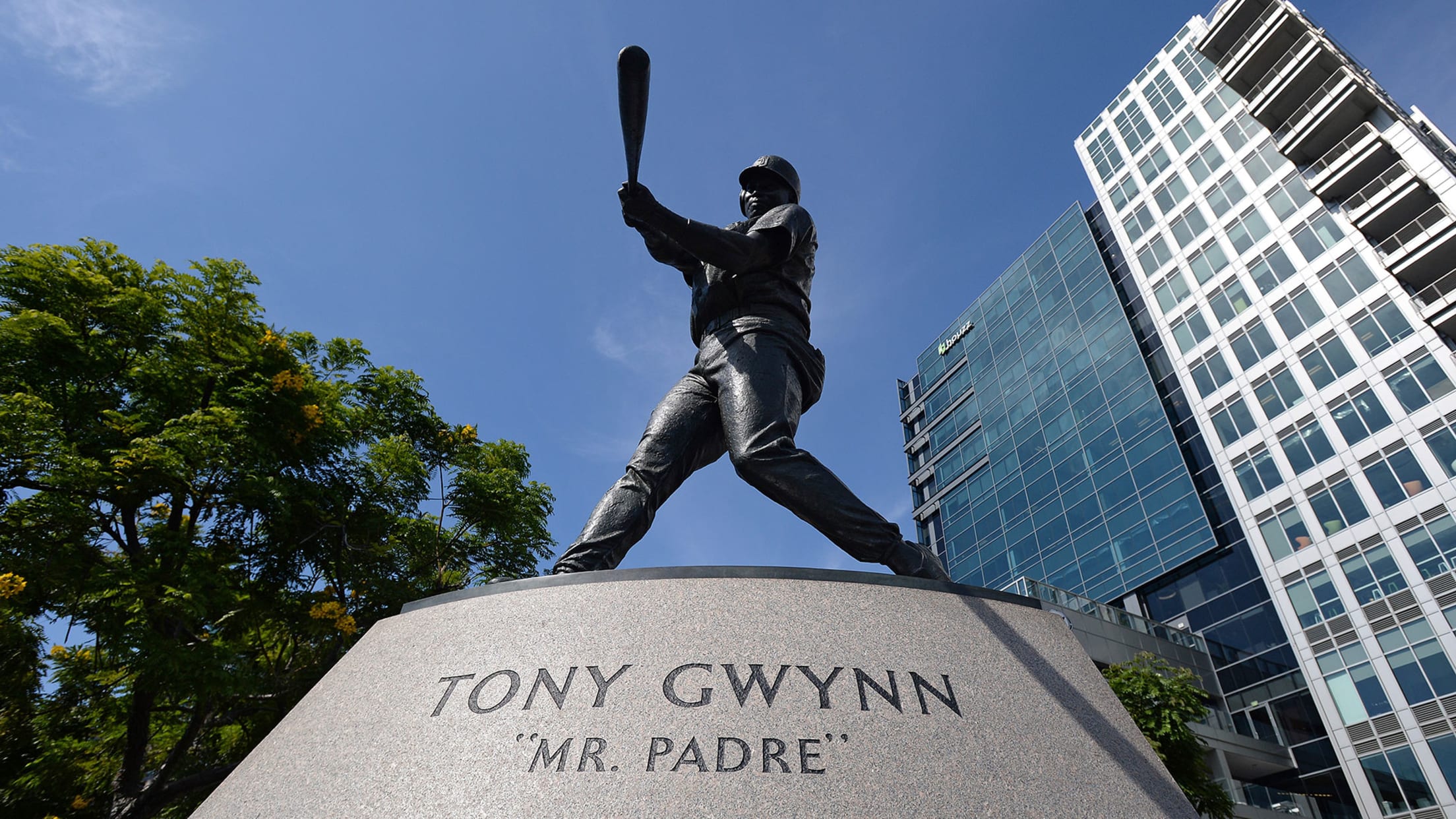

As Gwynn racked up numbers, he also earned the love of a city. A statue of Gwynn, mid-swing, adorns the park area beyond the outfield at Petco Park. When Gwynn was inducted into the Hall of Fame alongside Cal Ripken in 2007, San Diegans made the cross-country trek to Cooperstown. It’s still the largest crowd in Hall of Fame Weekend history. When Gwynn passed away of salivary gland cancer in 2014, the entire city mourned. Nearly 30,000 people attended his Petco Park memorial service.

Gwynn wasn’t always predestined to remain with the Padres. He’d signed a contract extension in 1991, but things changed significantly from ’91 to ’94 in San Diego. Padres ownership infamously unloaded superstars like Fred McGriff and Gary Sheffield -- within a month of each other in 1993 -- in what’s known as “the fire sale.”

In the winter following the 1993 season, Gwynn had two years remaining on his deal, and the Padres’ future wasn’t bright. A stroke of his pen changed that. Gwynn would remain in San Diego through '98 at $4 million per season.

“The San Diego discount,” Leitner says. “He knew he could've gone out, got the money, but he just didn’t want to.”

That laid the foundation for arguably the greatest era in Padres history. In the following months, general manager Randy Smith added key cogs like Ken Caminiti and Steve Finley. He’d also recently acquired Trevor Hoffman.

“Tony committing to the club at that moment was so huge to help us going forward,” Smith says. “What he did in ’94 meant so much to the city. But what Tony did, it also made it easier for me to say to ownership, ‘Hey, let’s go make these trades, let’s go put ourselves in a position to do something.’”

In the four seasons following the ’94 campaign, the Padres won two division titles and one NL pennant. Gwynn’s faith had been rewarded.

Tony committing to the club at that moment was so huge to help us going forward. What he did in ’94 meant so much to the city.

Former Padres GM Randy Smith

Chapter 2: ‘They’re going to hit me’

April 24, 1994: Jack Murphy Stadium

Padres 6, Phillies 5 (Box)

1st: Hit by pitch (by Curt Schilling)

3rd: Single to CF (off Schilling)

4th: Single to LF (off Schilling)

6th: Ground ball double play (against Jeff Juden)

8th: Single to RF (off Doug Jones)

Batting average: .448

Gwynn’s greatness didn’t rub anyone the wrong way. He was simply too genuine. But sometimes, his greatness was too much to comprehend. On April 23 against the Phillies, Gwynn went 5-for-5 with a double and a home run. For anyone else, it’d be a career night. For Gwynn, it was one of nine five-hit games.

During home games in the early ‘90s, Gwynn’s wife, Alicia, brought their son, Tony Jr., to the ballpark, where he’d watch the game, then join his father in the clubhouse afterward. The two almost always drove home together.

Following his five-hit game against Philadelphia, the elder Gwynn offered a prediction during that car ride home. It confused the 11-year-old Tony Jr.

“They’re going to hit me tomorrow,” he said.

Gwynn explained that the Phillies thought he was stealing signs. By all accounts, he was doing no such thing. Five hits in five at-bats wasn’t out of the ordinary for Tony Gwynn, after all.

The next day, Schilling was on the mound for Philadelphia. The first pitch he threw to Gwynn was a fastball at his right knee. Gwynn -- whose infectious laugh was a defining characteristic -- took on a different persona for a moment.

“He got up and he jawed at Schilling the whole way to first base,” Gwynn Jr. recalls. “That was something my dad never did. The very next at-bat, he hit [a single] right up the middle.”

An inning later, he knocked another base hit — this time to the opposite field against Schilling — as the Padres poured it on early. It exemplified the way Gwynn could do things with a bat that few other hitters could do.

Sometimes it felt like he had a steering wheel on his bat, and he could put the ball exactly where he wanted.

Orel Hershiser, who faced Gwynn in 11 plate appearances in 1994, as many as any other pitcher

“Sometimes it felt like he had a steering wheel on his bat, and he could put the ball exactly where he wanted,” says Hershiser, who faced Gwynn in 11 plate appearances in 1994, as many as any other pitcher (and “held” him to a .625 average in the process).

Following Gwynn’s single off Schilling in the third, he put his head down and ran to first base. But, according to Gwynn Jr., he did so with more than a touch of satisfaction.

“That was the tone-setter for the rest of the season,” Gwynn Jr. recalls.

Chapter 3: Chasing .400

May 16, 1994: Wrigley Field

Cubs 4, Padres 2 (Box)

1st: Groundout to second base (against Anthony Young)

4th: Bunt popout to pitcher (off Young)

7th: Groundout to 1B (off Young)

9th: Walk (against Randy Myers)

Batting average: .398

Four hits every 10 at-bats; a minimum of 3.1 plate appearances every team game.

When Gwynn bounced to first base in the seventh inning on May 16, it was the last time his season average sat above .400. He’d spend the next three months attacking that number like no modern-day hitter had ever done.

Nearly 20,000 people have played Major League Baseball. Twenty of them hit .400. That ratio is dwindling by the day. Five accomplished the feat more than once. Rogers Hornsby, Ty Cobb and Ed Delahanty did so three times. Every one of those seasons took place before color television.

“I had never been involved with anyone hitting at that level, but you realize how hard it is to hit .400 right away,” says Merv Rettenmund, the Padres' hitting coach in 1994. “He'd be at .395 or something, he'd go 2-for-4 with two hard-hit lineouts, and the batting average wouldn't go anywhere.”

Jim Riggleman, the Padres' manager in 1994, puts it another way: “Do you know how hot you’ve got to be to bring your average up 24 points when you’re hitting .370?”

I had never been involved with anyone hitting at that level, but you realize how hard it is to hit .400 right away.

Merv Rettenmund, the Padres' hitting coach in 1994

Since Gwynn’s quest in 1994, no player has eclipsed .380. (Coincidentally, Paul O’Neill of the Yankees carried a .400 average through June 16 of that season, a full month longer than Gwynn, but finished with an AL-leading .359.) As league-wide batting averages have fallen, so have the averages of batting champs. Larry Walker hit .379 in ’99. Ichiro Suzuki batted .372 five years later. But since the start of 2011, the highest single-season average is .348, belonging to Miguel Cabrera in '13 and DJ LeMahieu in '16. LeMahieu’s mark was aided by Coors Field.

“Back then, Colorado was a relatively new franchise,” says Brad Ausmus, who was a catcher on the ’94 Padres. “He would have hit .400 if he played for the Rockies. I remember consciously thinking that at the time.”

There are league-wide trends that have reduced batting averages to their lowest point since 1968. For one, pitchers are throwing harder and smarter, and they’re being used optimally. Plus, it’s smart baseball to sacrifice a few points of average for slugging or on-base percentage. There’s also a trove of batted-ball data, which has led to better defensive alignments. But those closest to Gwynn laugh at the notion of a shift.

“The game is definitely different now, and there are a lot of hits on the field that hitters aren’t taking,” says Hershiser. “But Tony would’ve worn the shift out. If you decided to shift on him, he’d take four hits to wherever you weren’t.”

Chapter 4: Lessons from a laundry bin

June 21, 1994: Jack Murphy Stadium

Padres 4, Dodgers 3, 13 innings (Box)

1st: Sacrifice fly to CF (off Tom Candiotti)

3rd: Single to 3B (off Candiotti)

6th: Single to CF (off Candiotti)

8th: Strikeout looking (against Brian Barnes)

11th: Flyout to CF (off Todd Worrell)

13th: Single to LF (off Rudy Seanez)

Batting average: .383

It’s hard to comprehend historic greatness when it takes place so predictably every single night. When Gwynn went 3-for-5 with a game-tying single and scored the game-winning run against the Dodgers, it was a standard June evening.

“It took a while for everyone to appreciate what he was doing,” Smith says. “Probably because to him, it was what he expected. He thought he was a .400 hitter. He never thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m hitting .392.’ He thought, ‘OK, I got a couple hits tonight and I’ll get a couple more tomorrow.’”

Gwynn was generally hard on himself. Tales abound of the team bus arriving after a road trip and Gwynn heading straight to the batting cage

“He’d grumble and fuss,” Leitner says. “He could go 3-for-4, and I'd say, 'Hey, Tone, good game,' and he'd say, 'Nah, I'm way off right now.' … That wasn't an act. To him, in his hitting brain and with his muscle memory, he was off.

“I always heard that through his entire career. In '94, I never heard that once.”

Even by Gwynn’s standards, he didn’t slump in 1994. His longest hitless drought lasted two days. In games that he started, Gwynn was held hitless just 16 times. On those car rides home from the ballpark, Tony Jr. recalled a “calm” version of his father.

“He was tough on himself,” Gwynn Jr. says. “Like: ‘Man, I can’t stay back for nothing.’ Or, ‘Man, I’m pulling off everything.’ There was a lot less of that in ’94. It just seemed like he fell into a rhythm early and he never got out of it.”

No one needed a lesson about the nature of Gwynn’s greatness more than 11-year-old Tony Jr.

“I had the wrong idea about hitting,” he said. “I thought .300, .330 was normal. That’s what I grew up watching. I found out probably a very cruel way.”

Gwynn Jr. was allowed into the clubhouse early for one midsummer game. Ausmus’ average hovered around .240 for most of June, and feeling confident in himself, Tony Jr. called out Ausmus.

Gwynn Sr. was nowhere to be found. A playful Ausmus and third baseman Scott Livingstone picked up Gwynn Jr. and wrapped him in athletic tape. They threw him in the laundry bin, where Gwynn Jr. spent 15 minutes before a clubhouse manager was sent to the rescue.

“I thought I’d be in trouble,” Gwynn Jr. says. “I thought I’d never get to go to another game early.

“I remember, [my dad] sat down with me, and he said, ‘This is a job. For everybody here, this is their job. [Ausmus] is hitting .240, .250 -- and that’s not bad! He’s a good catcher. He’s a good baseball player.’ From that point on, I learned my lesson. … That might have been when I learned my dad was special from everybody else.”

Tony Jr. spent parts of eight seasons in the big leagues as a very useful roster piece. He hit .238.

Chapter 5: How to pitch Tony Gwynn

June 30, 1994: Jack Murphy Stadium

Mets 3, Padres 1 (Box)

1st: Single to CF (off Bret Saberhagen)

3rd: Double to LF (off Saberhagen)

6th: Lineout to CF (off Saberhagen)

8th: Strikeout swinging (against Josias Manzanillo)

Batting average: .391

Bret Saberhagen and the Mets came to town on an unusually cool weekend in Mission Valley at the end of June. Gwynn was a .400 career hitter against the two-time Cy Young Award winner, and Saberhagen was slated to start the opener.

One of Rettenmund’s favorite Gwynn memories was a matchup against Saberhagen. In the dugout before an at-bat, Gwynn told Rettenmund he’d be looking for Saberhagen’s changeup. Gwynn felt off-kilter against the pitch, and he guessed Saberhagen knew as much.

“He starts him off with a 97 mph fastball,” recalls Rettenmund. “Tony laces it into left-center field. I told him: 'You can’t be telling other people that. This doesn't make sense. You're thinking changeup and then busting his fastball. That’s not the way a hitter’s supposed to hit.'"

On the final day of June 1994, Gwynn lined a single in his first at-bat against Saberhagen. In the third, Saberhagen went down and away with a curveball -- a perfect pitch. Gwynn swatted it to left field for a double, giving him a .401 batting average during the calendar year beginning July 1, 1993. After finishing 2-for-4, that number sat at .399.

“He did things that were just a little bit different,” Rettenmund says. “There was just no way to pitch to him.”

Opposing pitchers took that mantra to heart.

“We used to joke: 'Just throw it down the middle, and make him decide,'” Hershiser says. “If you threw it away, he’d hit it in the six-hole. If you threw inside, he’d pull it down the line for a double. You’d think, throw it down the middle, that might confuse him.”

It rarely did. If Maddux couldn’t figure it out, no one could. It was Maddux, after all, who delivered the quintessential Tony Gwynn quote. Arguably the greatest pitcher of all time, Maddux once opined on pitching philosophy to the Washington Post. If every pitch looked the same out of his hand, Maddux said, those pitches would be near-impossible to hit.

“If a pitcher can change speeds, every hitter is helpless, limited by human vision,” Maddux said.

“Except,” he added, “for that [expletive] Tony Gwynn.”

Gwynn faced Maddux 107 times, more than any other pitcher. He batted .415, and he didn’t strike out once.

Chapter 6: The leap

July 12, 1994: Three Rivers Stadium

NL 8, American League 7 (Box)

1st: Groundout to 1B (against Jimmy Key)

3rd: Double to RF (off David Cone)

5th: Flyout to LF (against Mike Mussina)

7th: Groundout to 1B (against Pat Hentgen)

10th: Single to CF (off Jason Bere)

Batting average at the All-Star break: .383

There’s no moment that captures the essence of Tony Gwynn better than the 1994 All-Star Game in Pittsburgh. It was Gwynn’s 10th career Midsummer Classic, an event that he cherished dearly.

“He wasn’t in the playoffs every year, so that was the ultimate to him,” Leitner says.

Gwynn had been on the losing end of five consecutive All-Star Games with the NL. That didn’t sit well with him, and he was the only National Leaguer to play all 10 innings that night, going 2-for-5, which equates to a .400 average (naturally). He led off the 10th with a single.

Moises Alou followed with a double to the gap, and Gwynn decided to win the game right there, speeding around the bases. Albert Belle fielded and threw to Cal Ripken, who relayed to Ivan Rodriguez.

The throw was on the money. Gwynn slid safely under the tag. He waited for the call from home-plate ump Paul Runge. Then, in a moment of pure, unbridled joy, Gwynn leapt. He pumped his left fist, and he leapt again, springing off the stadium’s AstroTurf.

Never mind that the game was merely an exhibition. Never mind that Gwynn’s two hits wouldn’t help his quest for .400. Gwynn had helped win a baseball game, and by God, he was going to celebrate.

“He just played the game hard,” says Hoffman. “Whether it was an exhibition, regular season or postseason game. He just loved playing.”

That moment sparked a surge. Gwynn came out firing to begin the second half. He went 18-for-38 during the first week, including six hits during a doubleheader in Philly. That raised his average to .393. The chase was on.

“Four hard-hit balls a day,” Riggleman says. “It was just a matter of: 'Do they go in a hole or do they get caught?' He was phenomenal. It was left-handed pitchers, right-handed pitchers, left-handed sidearmers, velocity, sliders. He was just on everything.”

“It was amazing,” says Hoffman, who arrived in time to watch Gwynn hit .400 in the second half of ‘93. “There was no doubt in my mind he had the ability, and was probably going to get it done. Because I saw him do it every day -- he was a .400 hitter.”

After the All-Star break in 1994, Gwynn batted .423. He hit .475 in August.

Says Riggleman: “I think he clearly would have gone up another six, or eight, or 10 points with the direction he was going. Then? Nobody will ever know if he could maintain it. But it was just phenomenal. It was an honor to be around.”

Chapter 7: .394

Aug. 11, 1994: Astrodome

Padres 8, Astros 6 (Box)

1st: Single to CF (off Greg Swindell)

2nd: Groundout to 2B (against Swindell)

4th: Single to LF (off Dave Veres)

6th: Groundout to 1B (against Shane Reynolds)

8th: Single to RF (off Ross Powell)

Batting average: .394

While Gwynn was assailing one of baseball’s storied milestones, a more ominous storyline had developed. The sport was stricken with labor unrest. In late July, the players association set Aug. 12 as the strike date. Games would be played on Aug. 11. Then, players would walk off their jobs.

The Padres spent the final series of the season in Houston. Before they arrived, Rettenmund did some math. If Gwynn were to receive 13 at-bats in the three-game series, he needed nine hits for .400. Gwynn pounded out six hits instead, leaving him three hits short.

Three. Hits. Short.

A day later, Gwynn and a handful of other players showed up at Jack Murphy Stadium to grab items from their lockers. Publicly, the tone from the players association was positive. They hoped that the issues would be settled and the season would resume. Gwynn threw his support behind the players association.

“He didn’t even have a reaction to the .400 part,” Gwynn Jr. says. “His focus at the time was on getting back on the field.”

Privately, Gwynn wasn’t so optimistic for a resolution, and he almost never brought up .400. He didn’t voice an opinion publicly about his chances until years later at a charity banquet.

“I was the emcee, and he was one of the speakers,” Leitner recalls. “He had never told me this, and he didn't say it often. But he went up to the podium, and someone asked him about .400. He said, 'You know what? I know I would have done it.'”

“He didn’t really acknowledge it publicly,” says Tony Jr. “Nobody knew how he thought about it. It was only people he trusted. He didn’t want to be out there saying, ‘I would’ve done it.’ But I know the older he got, the stronger he felt about it. And I believe it, too. It was the damnedest thing.”

On Sept. 14, the remainder of the season was canceled. The last great Expos team wouldn’t play in October. Matt Williams’ quest for the home run record ended on 43. But 25 years later, Gwynn’s lost pursuit of .400 is especially lamentable.

He didn’t want to be out there saying, ‘I would’ve done it.’ But I know the older he got, the stronger he felt about it. And I believe it, too. It was the damnedest thing.

Tony Gwynn Jr.

He took home another batting title, settling at .394. It was the best mark of Gwynn’s career and remains the best since Williams’ 1941 campaign. In San Diego, the number is an iconic one. A local brewery crafted San Diego Pale Ale .394, with a markup of Gwynn’s sweet left-handed swing on the label. It’s a staple around the city.

Today, .394 is an unfathomable batting average. There isn’t a single active hitter who seems capable.

And yet, every time Gwynn’s .394 mark is discussed, it’s done with a doleful air of “What if?”

Chapter 8: What if?

When the 1994 season was cut short, the Padres had 45 games remaining. Gwynn, averaging slightly below 3.8 at-bats per game, would’ve received approximately 170 at-bats over the remainder of the season.

Assuming he played every night -- and, in pursuit of history, he probably would have -- Gwynn needed 71 more hits. Let’s disregard the external factors and look at Gwynn for what he was -- a .368 hitter during his five-year peak from 1993-97.

So, what are the chances Gwynn would’ve hit .400 in 1994? Well, what are the chances that a .368 hitter will notch 71 hits in 170 at-bats? Probability sets that number around 11 percent.

But we don’t need to hypothesize about imaginary .368 hitters. We have one: Gwynn himself.

If we pick a random stretch of 170 at-bats from peak Tony Gwynn (1993-97), what are the chances we’d pick one in which he had 71 hits?

Answer: 12.8 percent.

That number isn’t as high as those around Gwynn believe it should be.

“If you asked anybody that was around that team on a daily basis, most people would’ve bet on him hitting .400,” Smith says. “I know Tony thought he would. To me, if Tony thinks he’s going to do something, odds are he’s going to do it.”

“The only reason he never came close again was his health,” Rettenmund surmises, citing the creaky left knee that plagued the second half of Gwynn’s career. “That year, he was healthy, and he was roaring. He was running well. He was moving. And he smoked every ball, even the outs. He would’ve done it.”

That seems unlikely statistically. It’s hard to hit .400. It’s even harder to hit .418, which is what Gwynn would’ve needed to hit down the stretch to get to .400.

But the larger point is this: Gwynn had a chance. Roughly the same chance as a coin flip coming up heads three straight times.

Gwynn never got that chance. His season cut to black, with .394 forever stuck to his baseball card.

“At some point in August,” Gwynn Jr. says, “he realized it definitely wasn’t going to happen. The way my dad was, he was onto his next focus, which was the next season. He thought, ‘I’ve got to start preparing.’ That’s part of the reason he never spoke about it. He didn’t want to take time to think about it. It was almost like: 'I’m going to bury my head in the dirt, keep working.'

“And, ‘Hey, maybe I’ll do it next year.’”

Gwynn followed his 1994 season with .368 in ‘95, .353 in ’96 and .372 in ’97 -- all batting titles.

Not quite .400.

Never .400.

But if anyone could have, surely it was Tony Gwynn.