Yankees Magazine: Heart over Height

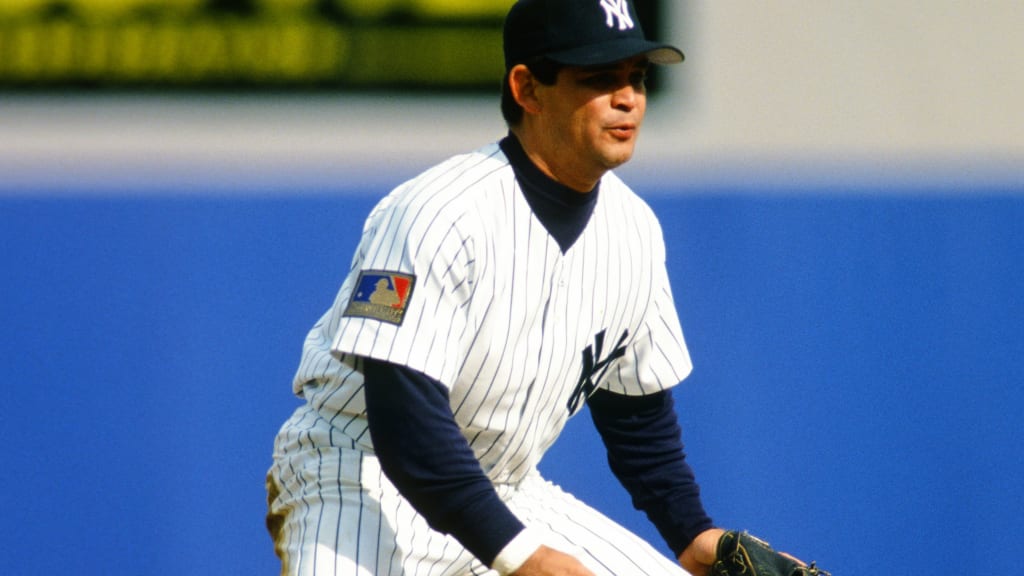

Former Yankees infielder Mike Gallego never let size get in the way of success

It’s not often that a misunderstanding leads to a better outcome or to a life-changing, legacy-defining decision. But when Mike Gallego hit the free-agent market following a seven-year tenure with the Oakland A’s, that’s exactly what happened.

The infielder, who had helped Oakland reach the World Series in 1988, 1989 and 1990 and win it all in ’89 against the San Francisco Giants, was finally at a point in his career in which getting a multiyear contract was the priority. But despite earning the respect of Oakland teammates, coaches and the club’s front office, Gallego received a far different message from the organization that had drafted him in 1981.

“I didn’t want to leave the A’s,” Gallego said over a casual dinner at Cold Beer & Cheeseburgers, a popular Gilbert, Arizona, restaurant that the 62-year-old frequents these days. “My agent was trying to communicate with [Oakland general manager] Sandy Alderson. I had always been working on one-year deals, but I was trying to get a multiyear deal so that my wife and I could finally make a long-term budget. Sandy felt that there were no other teams interested at the time, even though my agent was trying to convince him that there was another team calling. At some point along the way, Sandy stopped taking my agent’s calls, and I had to call him myself.”

Soon after Gallego picked up the phone, he realized that he had played his final game in green and gold.

“I told him that I wanted to stay,” Gallego recalled of his conversation with Alderson. “I didn’t care what the money was; I just wanted a multiyear deal. He responded by saying, ‘One of the toughest things to do in life is to say goodbye.’”

Having been told by his agent that New York was interested in giving him a long-term deal, Gallego wasted no time greenlighting a move to the Big Apple.

“As soon as I got off the phone with Sandy, I called my agent and said, ‘Tell the Mets that I’ll take their deal,’” Gallego recalled. “Then, there was a pause; a few seconds of silence.”

"The Mets?" the agent asked Gallego.

“He told me that the Yankees wanted me,” Gallego said. “I wasn’t sure why the Yankees would want me because they already had a few second basemen.”

Then, another pause.

They want you to play shortstop.

Gallego was taken aback. Never in his wildest dreams could he have imagined that he would get the chance to play shortstop for the most storied franchise in sports, and he certainly didn’t think that such an opportunity had been within his grasp for weeks.

“I was a second baseman who could play shortstop,” he said. “When I found out that the Yankees wanted me to be their shortstop, I had all kinds of emotions. I wouldn’t have had any concern about playing second base for anyone -- including the Yankees. But there’s a different level of prestige associated with being the Yankees’ shortstop. It’s astronomical. It’s pretty simple: You’re the guy.”

***

Gallego’s road to becoming “the guy” in New York began in Pico Rivera, a small city in Southern California about 10 miles southeast of Los Angeles. He was one of six children in a close-knit family, where hard work was an enduring characteristic.

“I thought I was going to go to El Rancho High School, where my older brother played football and baseball and was a track star,” said Gallego, who currently serves as a player development staff coach for the Los Angeles Angels after having spent several years as a big league coach. “One day, he told me that I was going to St. Paul High School in Santa Fe Springs. The gangs had overtaken El Rancho, and it was risky just to walk home after school.”

Enrolling Gallego at the private Catholic school wasn’t easy for the family. Gallego’s father worked as a gravedigger at a local cemetery, and the terms of the scholarship that Gallego accepted mandated that he play both baseball and football.

“I was just trying to survive back in high school, but when I look back on that time, I realize that the routine we had prepared me for life as a professional baseball player.”

It didn’t take long for Gallego -- who, at 15 years old, began dating a cheerleader at the school named Caryn, now his wife of 40 years -- to make a big impression on the diamond and the gridiron, even though he was routinely competing against guys who were much bigger than he was.

Standing about five and a half feet tall, Gallego never gave coaches reason to doubt him, as his play spoke for itself. Had he been a few inches taller, Gallego believes that he would have been drafted out of high school, but instead, he went the collegiate route.

“I had a scout from the Pittsburgh Pirates telling me that they wanted to draft me,” Gallego said. “But right before the Draft, they backed off. They decided that they wanted to see me play in college because of my size.”

Prior to informing a number of colleges that he was focused on playing professionally out of high school, Gallego reached out to Arizona State University, the one school he coveted most of all.

“I sent a letter to [Sun Devils head coach] Jim Brock,” Gallego said. “I was always interested in their school, their ballpark and their reputation. He responded by saying that although I was a good player, they looked for power hitters at ASU. He went on to say that I just didn’t fit their build, and I didn’t hit enough home runs to be on their club.”

The feedback that Gallego got from the Pirates and from Arizona State changed his attitude. For the first time, he had a chip on his shoulder. He became determined to prove that his size didn’t matter on the diamond; that his ability and mental fortitude would instead pave the way to a successful baseball career.

Gallego also remained confident that his height was a positive factor between the white lines.

“I always felt that my size enhanced me as a fielder because I was lower to the ground,” he said. “A key element to fielding is staying low, and I always knew how to keep my head at that level and keep my eyes on ground balls. I could see that first hop better than anyone else, and I never missed a hop.

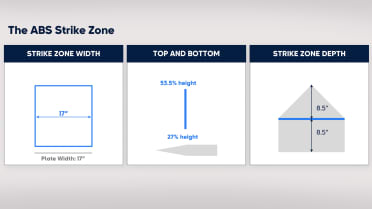

“Pitchers had to throw in the lower strike zone against me,” Gallego continued. “They couldn’t throw breaking balls for strikes, and because of that, I got a lot of fastballs. A high fastball is the hardest one to hit, but the lower ones don’t have as much movement, as much pop or as much rise. Pitchers were putting more effort toward getting the baseball into the strike zone when I was at the plate. Advantage 5-6.”

With his high school days dwindling, Gallego dealt with the first misunderstanding of his baseball life, which like the one that led him to the Yankees more than 13 years later, resulted in an incredibly surprising and joyous outcome.

“My high school baseball coach came to my Spanish class and knocked on the window,” Gallego said. “He told me that there was a scout at the school to see me. It sounded like he was saying that the scout was from East L.A. College. After school, I went out to the field and did some hitting and fielding drills for him. The coach said that he had seen enough, and he was going to give me a full ride.”

Content with the idea that he would have a chance to play baseball at East Los Angeles College, which is not known to have an elite athletic program, Gallego received a letter in the mail that changed the trajectory of his life.

“A few days later, I got an envelope from UCLA, not East L.A.,” he said. “That was a big difference.”

Longtime UCLA coach Gary Adams had seen Gallego play in an All-Star tournament. The Bruins’ skipper was impressed with the infielder’s passion and hustle, and unbeknownst to Gallego, he sent an assistant coach to his high school.

“Gary Adams saw the attitude I had,” Gallego said. “He was a small guy, and he loved how tall I played.”

Gallego played for UCLA for three years before getting selected by the A’s in the second round of the 1981 Draft. He had several productive games in college, but none more memorable than a thriller during his freshman season against the very coach who told him that he didn’t hit for enough power.

“I will never forget my first game against ASU,” Gallego said. “I ended up hitting a game-winning home run in the ninth inning. I can still remember coming around third base and making eye contact with Jim Brock. I just said, ‘Not enough home runs for you?’ I don’t think he even remembered the letter he wrote, but that was my first ‘remember me’ moment. That was the first time I realized that I could really play this game.”

***

As Gallego set out to prove that he could really play the game at the professional level, he encountered adversity more significant than anything he had faced on the field. A routine physical in Spring Training of 1983 led to further exams -- which revealed testicular cancer.

At 22 years old, Gallego, who had been invited to his first big league camp that year, dealt with a wide range of emotions before gaining a greater perspective from an unexpected source.

“I felt sorry for myself,” Gallego said. “I was scared; I was upset. But when I was sitting in the waiting room with my wife for the first radiation treatment, a kid who was about 6 years old asked me what I was there for. I told him testicular cancer, and he said, ‘That’s nothing. I’ve got brain cancer. Just keep a positive attitude, and you’ll be fine.’ I realized at that point that I shouldn’t be feeling sorry for myself. I needed to have a positive attitude about the whole thing.”

Once in remission, Gallego returned to the diamond, making his big league debut in 1985. As the A’s became a star-studded juggernaut, Gallego grew into a solid contributor. Beginning in 1988 -- Oakland’s first of three pennant-winning campaigns -- Gallego was on the field for at least 129 games each season.

The 1989 World Series is widely regarded as the most remarkable of the three Fall Classics that the A’s played in during that era, not only because it was the only one that they won or because it was played against their Bay Area rivals. A few minutes prior to Game 3 of the Series, San Francisco’s Candlestick Park began to shake: The region was encountering a magnitude 6.9 earthquake. The Loma Prieta earthquake caused massive destruction throughout the Bay Area, taking 63 lives and collapsing sections of both the Bay Bridge and the Nimitz Freeway.

For Gallego, who was not in the starting lineup that night, the experience that began at 5:04 p.m. remains one of the most memorable events of his career.

“I remember sitting in the locker room in Candlestick,” he said. “I could literally hear a rumbling in the locker room, which was underneath the stands. All of a sudden, the whole place started rocking. The legs of the chair I was sitting on were literally coming off the ground. I had been in some earthquakes before, but nothing like this. Someone on the clubhouse staff was yelling, ‘This is an earthquake! This place is coming down!’

“As soon as he said that, the power went out, and it was pitch black,” he continued. “We were all trying to get out of one door that led to a parking lot. I got about halfway to the door, and I turned around and went back to my locker. Everybody thought I was crazy for going back for my glove, but I just kept saying, ‘You guys can hit, but this is what got me here.’”

When Gallego made it out to the parking area, he looked up at the stadium lights.

“They looked like fishing poles, just swaying back and forth,” he said. “They were ready to snap.”

Ten days later, the Fall Classic resumed, and Gallego and the A’s completed a sweep of the Giants. The team returned to the World Series in 1990, falling to the Cincinnati Reds in four games. Gallego wrapped up his time in the Bay area with his best season to date in 1991, batting .247 with 12 home runs and 49 RBI in 159 games.

Gallego’s tenure in Oakland not only paved his path to pinstripes, but it also served as confirmation that although he was undersized, it didn’t matter.

“I was standing between José Canseco and Mark McGwire for the national anthem during my third World Series,” he said. “The cameraman went right over my head and missed me. I didn’t realize until then that I was that short; I just believed that I always played as tall as anyone. It was all about my attitude.”

***

Gallego had garnered respect from all corners of the sport, and that included Yankees general manager Gene Michael, who in the early 1990s was in the process of assembling a team that would ultimately become a dynasty.

As part of an effort to build a formidable supporting cast around Yankees captain Don Mattingly -- and to improve the clubhouse culture for a team that had not made it to the postseason since 1981 -- Michael signed Gallego to a three-year contract.

“Gene Michael liked how I played the game,” Gallego said. “He told [new Yankees manager] Buck Showalter that I was a gamer. He felt like I was one of the pieces to the puzzle that would help change the chemistry of the clubhouse.”

The Yankees also brought in Wade Boggs, Paul O’Neill, Jimmy Key and Mike Stanley in the early part of the decade, and as those veteran All-Stars contributed to drastic improvements on the field and in the clubhouse, homegrown center fielder Bernie Williams also began to emerge under Showalter’s guidance.

“We all had the same attitude toward the organization, the same respect for the Yankees,” Gallego said. “Other than Don Mattingly and Wade Boggs, there weren’t any superstars, but we were all solid players with a shared focus on winning. Gene Michael and George Steinbrenner felt that a cultural change was desperately needed. Don Mattingly finally got some guys who were willing to follow his lead. Donnie took to us as much as we took to him. Buck allowed us to create an environment in which we kept each other accountable. There was pride in putting on the Yankees uniform again, and that had been lost a little bit prior to those years.”

Gallego arrived in Fort Lauderdale for his first Spring Training with the Yankees in 1992, and he immediately felt a sense of pride, simply because he was wearing the pinstripes.

“When you walk into the clubhouse and Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford are there, it’s different from anything else you could ever experience,” Gallego said. “Whitey was in full uniform; Mickey Mantle was having a cup of coffee and laughing. That’s when I realized how special it was to be in the same uniform as those guys.”

Adding to his good feeling, Gallego was handed a No. 2 jersey.

“I knew the single digits were worn by some of the greatest players, guys like Mickey Mantle,” Gallego said. “I wasn’t sure I was worthy of that number at the time.”

Gallego didn’t get off to the start he had wanted with the Yankees. For much of that 1992 season, he was dealing with the effects of plantar fasciitis, which the Mayo Clinic describes as inflammation of a thick band of tissue that runs across the bottom of each foot and connects the heel bone to the toes. Although the condition was not as commonly diagnosed then as it is today, the symptoms were the same -- stabbing heel pain when running and at other times.

“No one knew how to deal with it,” Gallego said. “I could walk normally, but I couldn’t run. Buck felt like he couldn’t depend on me because of this injury that didn’t look bad until I tried to run. I couldn’t explain what I was feeling.”

Even though he played just 53 games during his first season in the Bronx, Gallego showed flashes of greatness. He collected three hits, including a home run, against the Brewers in May and then put up the same production at Fenway Park in a June tilt with the Red Sox. He also finished the season on a positive note, hitting safely in eight of his last 12 games.

But when Spring Training opened in 1993, he still had a lot to prove to Showalter. Coming out of camp, the skipper was only planning on using Gallego as a platoon player -- not exactly the role that the infielder originally envisioned when he signed his three-year deal with the Yankees.

Feeling as if he had more to gain than lose, Gallego made a bold move that April, going public with the frustration he felt about his diminished role.

“I told the media that I felt like Buck wasn’t writing out the lineup cards, and that decisions on who was playing came from above,” Gallego said. “He wasn’t happy with me, but all I was trying to do was get his attention. We had a man-to-man discussion, and it got kind of loud. But, at the end of it, he put me in the lineup that night against the Angels.”

A few hours after their conversation, Gallego again got Showalter’s attention, hitting two home runs against left-hander Chuck Finley, a two-time All-Star. Gallego remained in the lineup, starting 119 games and posting a career-high .283 batting average with 10 home runs and 54 RBIs in ’93.

“I wanted to prove to Buck and the Yankees organization that I was worthy of the contract that I received,” Gallego said. “When I ended up playing as well as I did in 1993, I was satisfied with my performance, not only for the fans and the organization but also because of the contract I was given. It meant a lot to me to be able to go out there every day and be depended on.”

As a team, the Yankees made significant strides, as well. The club won 88 games in 1993 and finished second in the AL East. The 12-game improvement from the previous year set the foundation for even greater success in the second half of the decade.

Reflecting on what he had accomplished in 1993, Gallego said he found inspiration from being around Mattingly.

“He had the ultimate respect throughout the industry based on the accolades he brought with him,” Gallego said. “When you combine that with the man he is, it was amazing to be his teammate. He respected kids, fans, the media, his teammates, his coaches -- he put everyone on a higher pedestal than himself. He didn’t expect that people simply respect him because of what he had done; he wanted to continue to earn everyone’s respect. He cared about people, and he was the fiercest competitor I have ever been around.”

Among the memories Gallego has of Mattingly, the one that stands out the most didn’t take place on the field, but it speaks volumes about the former Yankee captain’s off-the-charts work ethic.

“I decided to come to the Stadium early before a day game,” Gallego said. “I got there at 7 a.m., got my stuff on and walked out to the cage, thinking that I would hit for a few hours before anyone else showed up. As I’m walking down there, I hear the pitching machine working. Don Mattingly was already down there, just tracking pitches. About 300 baseballs were just sitting in the net behind him. He had taken every pitch, just watching the ball come over the plate. I couldn’t believe that he had taken a whole bucket of balls without swinging the bat. Well, that was his fourth bucket. He took about 1,200 baseballs without swinging at one of them, just to get himself to see the ball better.”

In 1994, Gallego played in 89 of the team’s 113 games during the regular season, and with the best record in the American League, it appeared that the Yankees had a legitimate chance to finally return to the World Series. But, following a labor strike that began in mid-August, the 1994 postseason was canceled. Just like that, a year that had so much promise was done -- as was Gallego’s tenure in pinstripes.

“We felt bad that we weren’t able get Donnie into the World Series,” said Gallego, who returned to Oakland in 1995 before playing his final two seasons in St. Louis. “But I’m proud to still be mentioned as one of the players who helped create a culture for a team that went on to be a dynasty. It’s a little piece that the guys who played for the Yankees in the early ’90s can take with us.”

More than that -- in fact, more than anything he has done throughout his four-plus decades in professional baseball -- Gallego is supremely proud of wearing the pinstripes and specifically donning No. 2 before it became immortalized by Derek Jeter.

“I played in three World Series with Oakland and coached in another one with the Colorado Rockies,” said Gallego, who finished his 13-year playing career with a .239 average, 42 home runs and 282 RBIs. “But to say that I wore the pinstripes and wore such a special number, that’s my ultimate accomplishment in the game.

“It was never my number; it was always meant to be worn by Derek Jeter,” Gallego continued. “I was just a blip in the story of that number, but that blip is something that my family and I are very proud of. I will be able to tell my grandchildren that I was special enough to wear that number for the New York Yankees. I’m just proud to say that I kept it warm for him until Derek was ready to get to the big leagues.”

Before Gallego’s mid-February dinner at Cold Beer & Cheeseburgers wrapped up, the father of three reflected on just how fast the decades have passed by.

“It feels like it was just yesterday that I was telling my agent that I wanted to sign with the Mets,” he said. “I remember him informing me that it wasn’t the Mets and having that feeling of, ‘I’m going to be a Yankee!’”

Alfred Santasiere III is the editor-in-chief of Yankees Magazine. This story appears in the May 2023 edition. Get more articles like this delivered to your doorstep by purchasing a subscription to Yankees Magazine at www.yankees.com/publications.