History of Black Baseball: Part I

Welcome to a serial online anthology that celebrates the indispensable contributions of Black people to our game. There have been collections focused on the lives and special skills of African Americans ("Blues: An Anthology," by W.C. Handy, 1926; Nancy Cunard’s "Negro," 1934). There have been anthologies about baseball—the Fireside books, the Armchair books, and others--but never has there been one about Black Baseball.

An early stab at a title for this venture was The Negro Leagues Anthology, in line with Major League Baseball’s decision to welcome seven of the Black-only leagues of 1920 to 1948 as majors, conceptually and statistically. But that title would have narrowed the anthology unnecessarily. The African American experience in recorded baseball goes back to a club in Brooklyn in 1859, the aptly named Unknowns (foretelling Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man").

Black and white teams played ball against each other, beginning in 1869. Integrated clubs followed, at the collegiate level and in the minor and major leagues. But the color line was drawn in the International League on July 14, 1887 and the big leagues followed, in the “gentleman’s agreement” that endured until 1947.

Several scholars have made notable contributions in this field—either narrower or deeper, earlier or later—but for one who would grasp the great story of Black Baseball in broad strokes, this is, in my humble estimation, the best essay ever written, and thus occupies the leadoff spot in MLB’s Anthology of Black Baseball. We have chosen to offer it as Jules Tygiel (1949-2008) wrote it, in 1989. Certain historical facts herein may have been amended or expanded by later research, but not the author’s basic treatment; his text is left intact except for his own corrections and a few wording changes to reflect modern and more sensitive usage.

In "Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy" (1983), Tygiel conveyed that baseball’s racial integration was more than just Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson—that there were many other heroes, some of them integrating each of the minor leagues, especially in the South, while others played on, in segregated ball. Other books followed but also some notable essays. There may be no better person than him to introduce MLB's Anthology.

From a 1986 essay in the "SABR Review of Books": “… the Negro Leagues, ‘invisible’ during their best years, almost totally disappeared from American memory in the 1950s and 1960s. Even in the Black community, baseball fans savored the hard-won fruits of integration and turned their gaze away from the legacy of Black baseball. "The big league doors suddenly opened one day,” wrote sportswriter Wendell Smith, “and when Negro players walked in, Negro baseball walked out."

The entire subject of Black Baseball was once terra incognita, and despite arduous work by Robert Peterson, John Holway, Larry Lester, Phil Dixon, Leslie Heaphy, Gary Ashwill and others, much remains to be uncovered or reconstructed. But we can’t know where we’re going until we know where we have been.

This Anthology of Black Baseball, launching today, is a step in the right direction.

- John Thorn

In 1987, Major League Baseball, amidst much fanfare and publicity, celebrated the 40th anniversary of the finest moment in the history of the national pastime — Jackie Robinson’s heroic shattering of the color barrier. But baseball might also have commemorated the centennial of a related, but far less auspicious event — the banishment of Black people from the International League in 1887, which ushered in six disgraceful decades of Jim Crow baseball. During this era, some of America’s greatest ballplayers plied their trade on all-black teams, in Negro Leagues, on the playing fields of Latin America, and along the barnstorming frontier of the cities and towns of the United States, but never within the major and minor league realm of “organized baseball.” When slowly and grudgingly given their chance in the years after 1947, Black players conclusively proved their competitive abilities on the diamond, but discrimination persisted as baseball executives continued to deny them the opportunity to display their talents in managerial and front office positions.

Scattered evidence exists of Black people playing baseball in the antebellum period, but the first recorded black teams surfaced in Northern cities in the aftermath of the Civil War. In October 1867, the Uniques of Brooklyn hosted the Excelsiors of Philadelphia in a contest billed as the “championship of colored clubs.” Before a large crowd of black and white spectators, the Excelsiors marched around the field behind a fife and drum corps before defeating the Uniques, 37–24. Two months later, a second Philadelphia squad, the Pythians, dispatched a representative to the inaugural meetings of the National Association of Base Ball Players, the first organized league. The nominating committee unanimously rejected the Pythian’s application, barring “any club which may be composed of one or more colored persons.” Using the impeccable logic of a racist society, the committee proclaimed, “If colored clubs were admitted there would be in all probability some division of feeling, whereas, by excluding them no injury could result to anyone.” The Philadelphia Pythians, however, continued their quest for interracial competition. In 1869, they became the first black team to face an all-white squad, defeating the crosstown City Items, 27–17.

In 1876, athletic entrepreneurs in the nation’s metropolitan centers established the National League, which quickly came to represent the pinnacle of the sport. The new entity had no written policy regarding Black people, but precluded them nonetheless through a “gentleman’s agreement” among the owners. In the smaller cities and towns of America, however, where underfunded teams and fragile minor league coalitions quickly appeared and faded, individual Black ballplayers found scattered opportunities to pursue baseball careers. During the next decade, at least two dozen Black ballplayers sought to earn a living in this erratic professional baseball world.

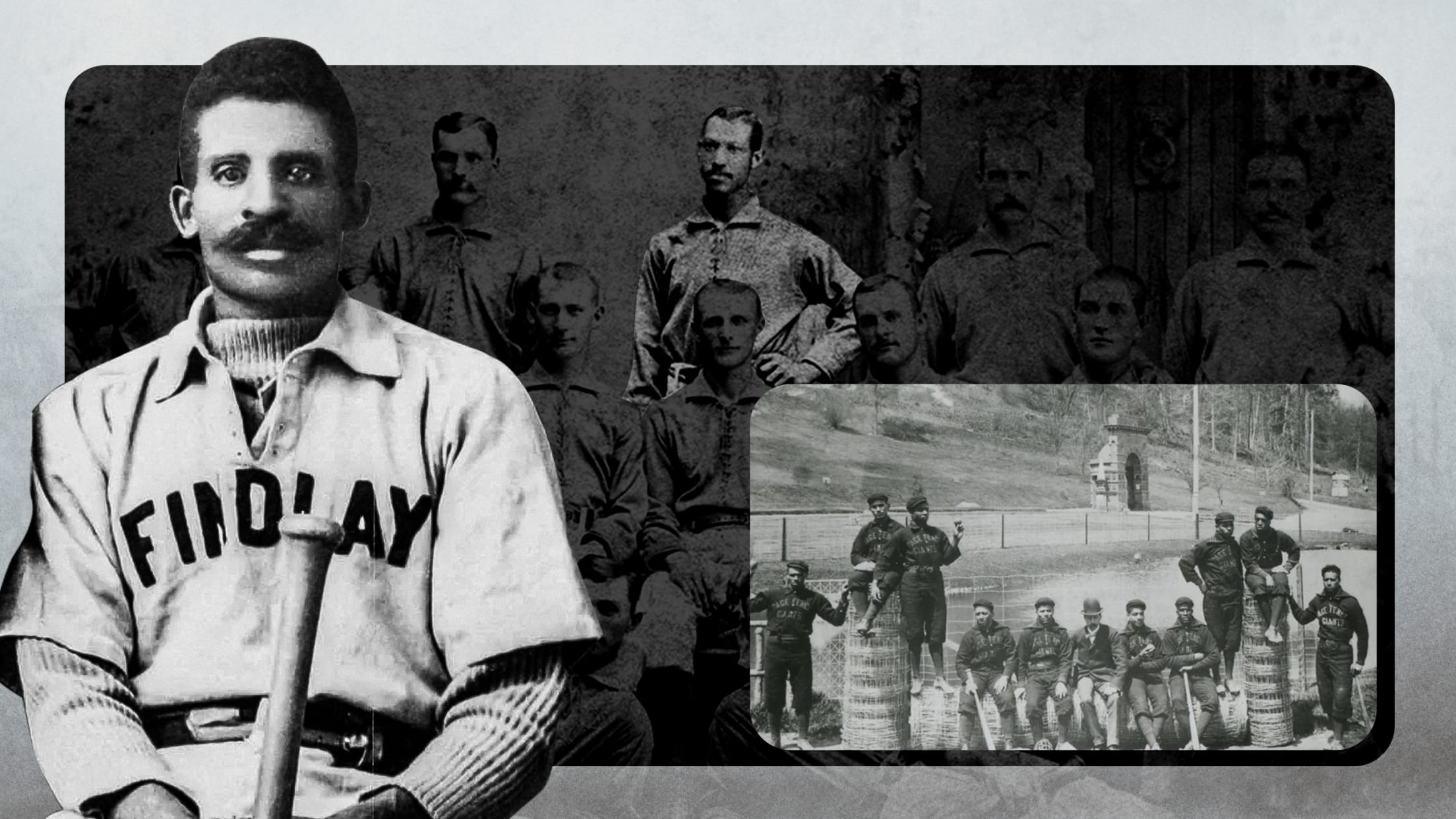

He is one of the best general players in the country and if he had a white face he would be playing with the best of them…. Those who know, say there is no better second baseman in the country.

Sporting Life on Bud Fowler, 1885

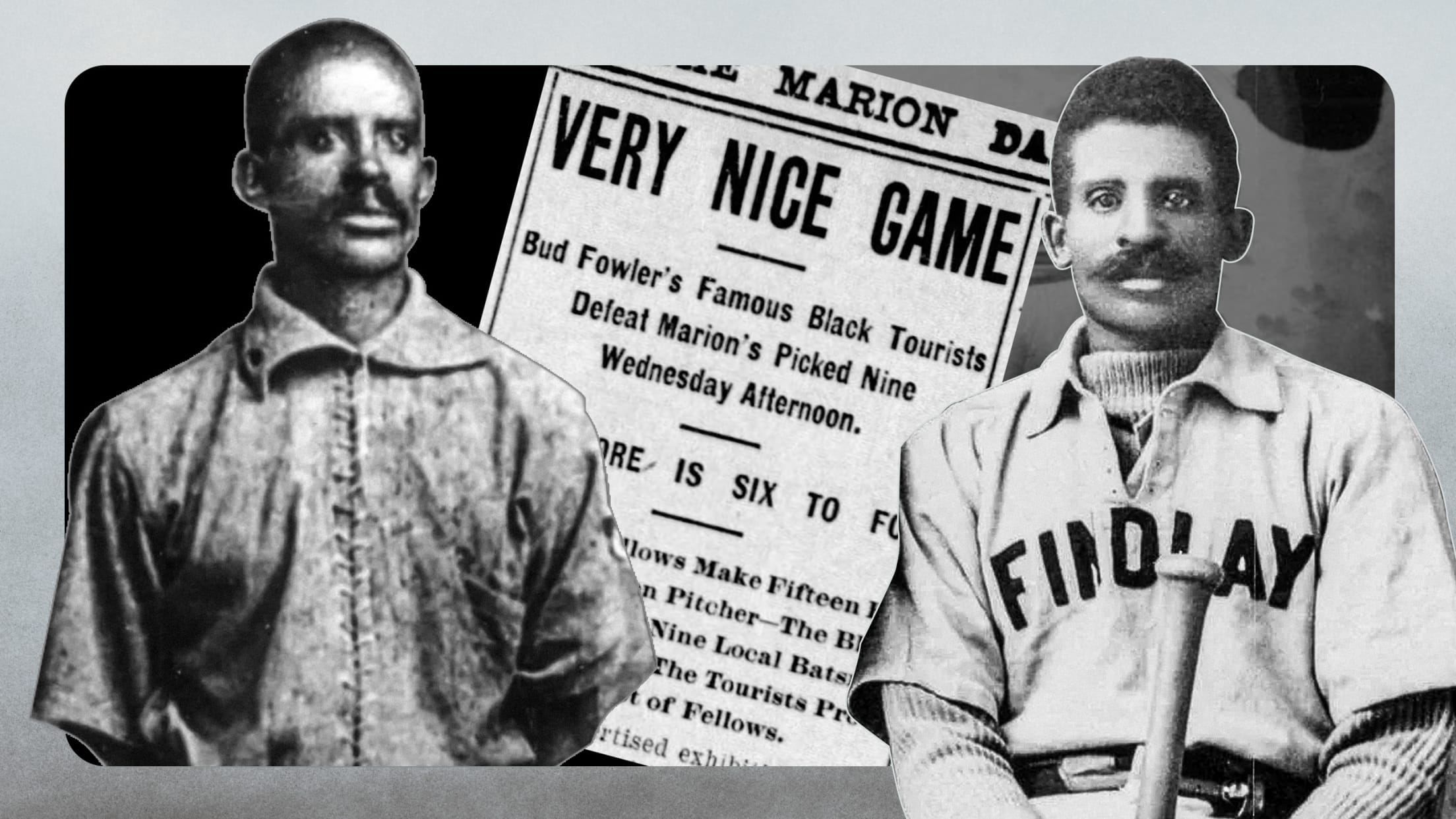

Bud Fowler ranked among the best and most persistent of these trailblazers. Born John Jackson in upstate New York in 1858 and raised, ironically, in Cooperstown, Fowler first achieved recognition as a 20-year-old pitcher for a local team in Chelsea, Massachusetts. In April 1878, Fowler defeated the National League’s Boston club, which included future Hall of Famers George Wright and Jim O’ Rourke, 2–1, in an exhibition game, besting 40-game winner Tommy Bond. Later that season, Fowler hurled three games for the Lynn Live Oaks of the International Association, the nation’s first minor league, and another for Worcester in the New England League. For the next six years, he toiled for a variety of independent and semiprofessional teams in the United States and Canada. Despite a reputation as “one of the best pitchers on the continent,” he failed to catch on with any major or minor league squads. In 1884, now appearing regularly as a second baseman, as well as a pitcher, Fowler joined Stillwater, Minnesota, in the Northwestern League. Over the next seven seasons, Fowler played for fourteen teams in nine leagues, seldom batting less than .300 for a season. In 1886, he led the Western League in triples. “He is one of the best general players in the country,” reported Sporting Life in 1885, “and if he had a white face he would be playing with the best of them…. Those who know, say there is no better second baseman in the country.”

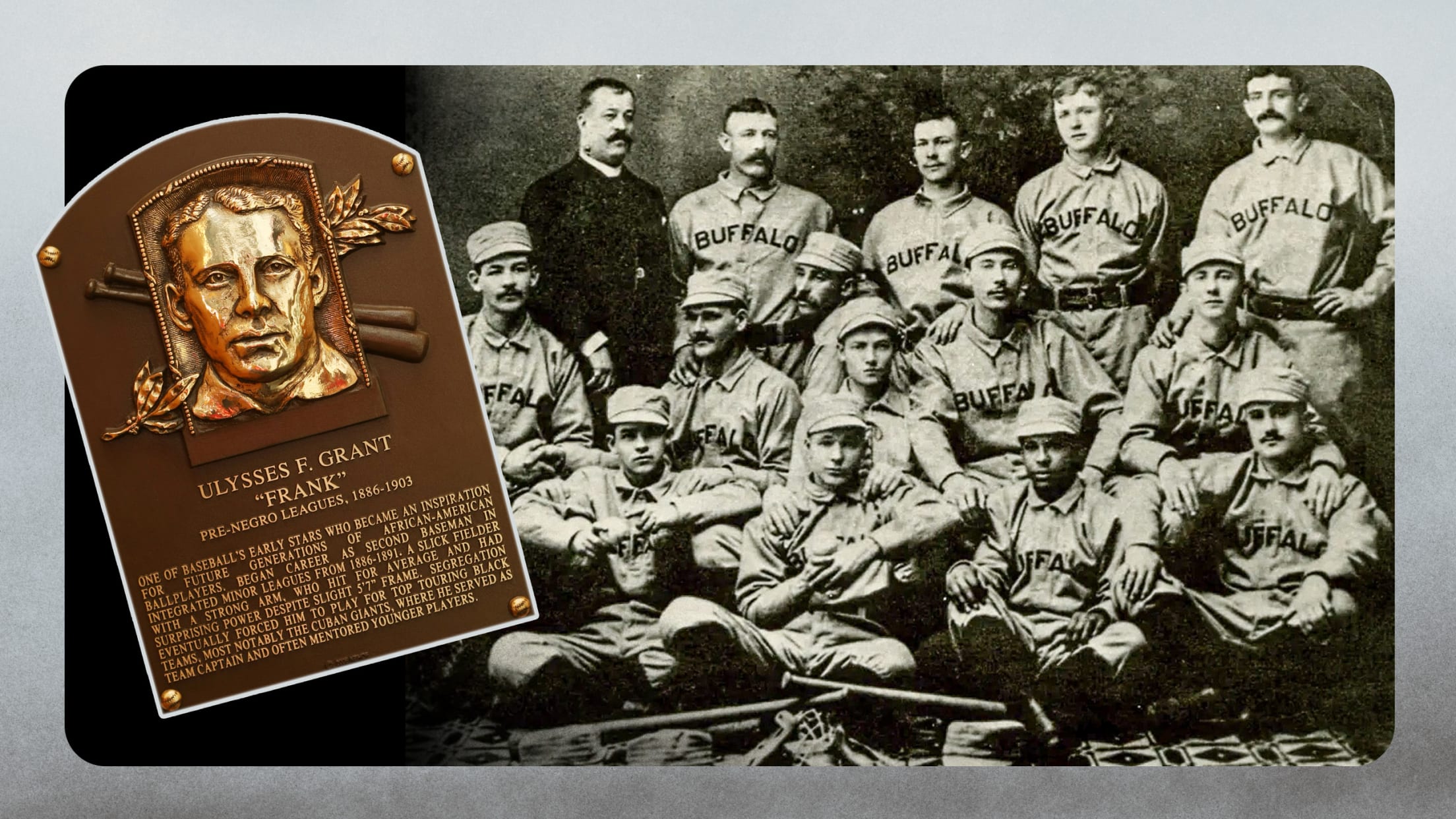

In 1886, however, a better second baseman did appear in the form of Frank Grant, perhaps the greatest Black player of the nineteenth century. The light-skinned Grant, described as a “Spaniard” in the Buffalo Express, batted .325 for Meridien in the Eastern League. When that squad folded he joined Buffalo in the prestigious International Association and improved his average to .340, third best in the league.

Although not as talented as Fowler and Grant, barehand-catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker achieved the highest level of play of Black people of this era. The son of an Ohio physician, Fleet Walker had studied at Oberlin College, where in 1881 he and his younger brother Welday helped launch a varsity baseball team. For the next two years, the elder Walker played for the University of Michigan and in 1883 he appeared in 60 games for the pennant-winning Toledo squad in the Northwestern League. In 1884, Toledo entered the American Association, the National League’s primary rival, and Walker became the first Black major leaguer. In an age when many catchers caught barehanded and lacked chest protectors, Walker suffered frequent injuries and played little after a foul tip broke his rib in mid-July. Nonetheless, he batted .263 and pitcher Tony Mullane later called him “the best catcher I ever worked with.” In July, Toledo briefly signed Walker’s brother, Welday, who appeared in six games batting .182. The following year, Toledo dropped from the league, ending the Walkers’ major league careers.

These early Black players found limited acceptance among teammates, fans, and opponents. In Ontario, in 1881, Fowler’s teammates forced him off the club. Walker found that Mullane and other pitchers preferred not to pitch to him. Although he acknowledged Walker’s skills, Mullane confessed, “I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used anything I wanted without looking at his signals.” At Louisville in 1884, insults from Kentucky fans so rattled Walker that he made five errors in a game. In Richmond, after Walker had actually left the team due to injuries, the Toledo manager received a letter from “75 determined men” threatening “to mob Walker” and cause “much bloodshed” if the Black catcher appeared. On August 10, 1883, Chicago White Stockings star and manager Cap Anson had threatened to cancel an exhibition game with Toledo if Walker played. The injured catcher had not been slated to start, but Toledo manager Charlie Morton defied Anson and inserted Walker into the lineup. The game proceeded without incident.

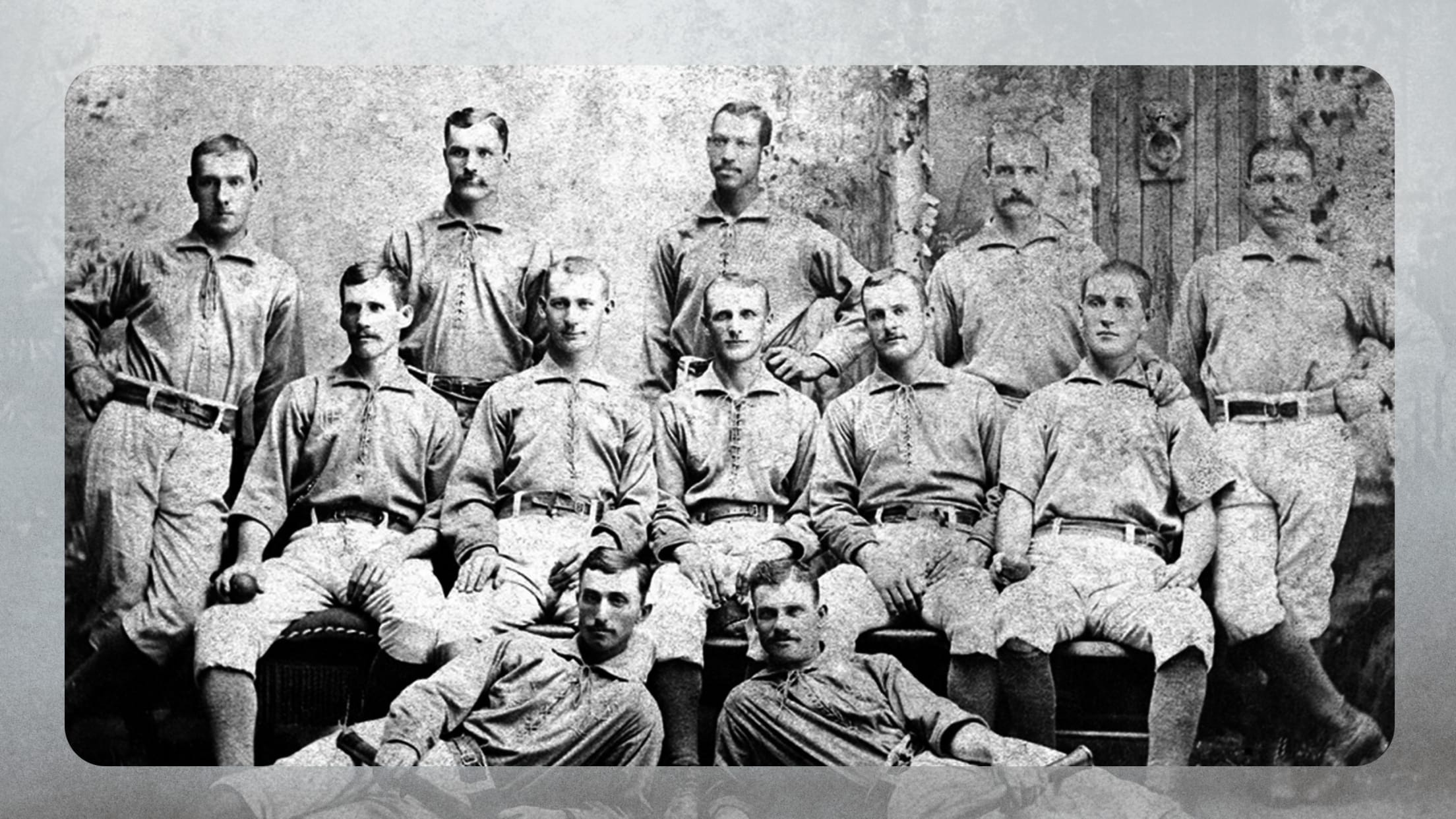

In 1887, Walker, Fowler, Grant, Higgins, Stovey, and three other Black players converged on the International League, a newly reorganized circuit in Canada and upstate New York, one notch below the major league level. At the same time, a new six-team entity, the League of Colored Baseball Clubs, won recognition under baseball’s National Agreement, a mutual pact to honor player contracts among team owners. Thus, an air of optimism pervaded the start of the season. But 1887 would prove a fateful year for the future of Black players in baseball.

On May 6, the Colored League made its debut in Pittsburgh with “a grand street parade and a brass band concert.” Twelve hundred spectators watched the hometown Keystones lose to the Gorhams of New York, 11–8. Within days, however, the new league began to flounder. The Boston franchise disbanded in Louisville on May 8, stranding its players in the Southern city. Three weeks later, league-founder Walter Brown formally announced the demise of the infant circuit.

Meanwhile, in the International League, Black players found their numbers growing, but their status increasingly uncertain. Six of the 10 teams fielded Black players, prompting Sporting Life to wonder, “How far will this mania for engaging colored players go?” In Newark, fans marveled at the “colored battery” of Fleet Walker, dubbed the “coon catcher” by one Canadian newspaper, and “headstrong” pitcher George Stovey. Stovey, one of the greatest Black pitchers of the nineteenth century, won 35 games, still an International League record. Frank Grant, in his second season as the Buffalo second baseman, led the league in both batting average and home runs. Bud Fowler, one of two Black players on the Binghamton squad, compiled a .350 average through early July and stole 23 bases.

These athletes compiled their impressive statistics under the most adverse conditions. “I could not help pitying some of the poor Black fellows that played in the International League,” reported a white player. “Fowler used to play second base with the lower part of his legs encased in wooden guards. He knew that about every player that came down to second base on a steal had it in for him.” Both Fowler and Grant, “would muff balls intentionally, so that [they] would not have to touch runners, fearing that they might injure [them].” In addition, “About half the pitchers try their best to hit these colored players when [they are] at bat.” Grant, whose Buffalo teammates had refused to sit with him for a team portrait in 1886, reportedly saved himself from a “drubbing” at their hands in 1887, only by “the effective use of a club.” In Toronto, fans chanted, “Kill the N-----,” at Grant, and a local newspaper headline declared, “THE COLORED PLAYERS DISTASTEFUL.” In late June, Bud Fowler’s Binghamton teammates refused to take the field unless the club removed him from the lineup. Soon after, on July 7, the Binghamton club submitted to these demands, releasing Fowler and a Black teammate, a pitcher named Renfroe.

The most dramatic confrontations between black and white players occurred on the Syracuse squad, where a clique of refugees from the Southern League exacerbated racial tensions. In spring training, the club included a catcher named Dick Male, who, rumors had it, was a light-skinned Black man named Richard Johnson. Male charged “that the man calling him a Negro is himself a Black liar,” but when released after a poor preseason performance, he returned to his old club, Zanesville in the Ohio State League, and resumed his true identity as Richard Johnson. In May, Syracuse signed 19-year-old Black pitcher Robert Higgins, angering the Southern clique. On May 25, Higgins appeared in his first International League game in Toronto. “THE SYRACUSE PLOTTERS,” as a Sporting News headline called his teammates, undermined his debut. According to one account, they “seemed to want the Toronto team to knock Higgins out of the box, and time and again they fielded so badly that the home team were enabled to secure many hits after the side had been retired.” “A disgusting exhibition,” admonished The Toronto World. “They succeeded in running Male out of the club,” reported a Newark paper, “and they will do the same with Higgins.” One week later, two Syracuse players refused to pose for a team picture with Higgins. When manager “Ice Water” Joe Simmons suspended pitcher Doug Crothers for this incident, Crothers slugged the manager. Higgins miraculously recovered from his early travails and lack of support to post a 20–7 record.

On July 14, as the directors of the International League discussed the racial situation in Buffalo, the Newark Little Giants planned to send Stovey, their ace, to the mound in an exhibition game against the National League Chicago White Stockings. Once again manager Anson refused to field his squad if either Stovey or Walker appeared. Unlike 1883, Anson’s will prevailed. On the same day, team owners, stating that “Many of the best players in the league are anxious to leave on account of the colored element,” allowed current Black players to remain, but voted by a six-to-four margin to reject all future contracts with Black ballplayers. The teams with Black players all voted against the measure, but Binghamton, which had just released Fowler and Renfroe, swung the vote in favor of exclusion.

Events in 1887 continued to conspire against Black players. On September 11, the St. Louis Browns of the American Association refused to play a scheduled contest against the all-Black Cuban Giants. “We are only doing what is right,” they proclaimed. In November, the Buffalo and Syracuse teams unsuccessfully attempted to lift the International League ban on Black players. The Ohio State League, which had fielded three Black players, also adopted a rule barring additional contracts with Black people, prompting Welday Walker, who had appeared in the league, to protest, “The law is a disgrace to the present age. . . There should be some broader cause — such as lack of ability, behavior and intelligence — for barring a player, rather than his color.”

After 1887, only a handful of Black players appeared on integrated squads. Grant and Higgins returned to their original teams in 1888. Walker jumped from Newark to Syracuse. The following year, only Walker remained for one final season, the last Black in the International League until 1946. Richard Johnson, the erstwhile Dick Male, reappeared in the Ohio State League in 1888 and in 1889 joined Springfield in the Central Interstate League, where he hit 14 triples, stole 45 bases, and scored 100 runs in 100 games. In 1890, Harrisburg in the Eastern Interstate League fielded two Black players, while Jamestown in the New York Penn League featured another. Bud Fowler and several other Black players appeared in the Nebraska State League in 1892. Three years later, Adrian in the Michigan State League signed five Black players, including Fowler and pitcher George Wilson, who posted a 29–4 record. Meanwhile Sol White, who later chronicled these events in his 1906 book, The History of Colored Baseball, played for Fort Wayne in the Western State League. In 1896, pitcher-outfielder Bert Jones joined Atchison in the Kansas State League where he played for three seasons before being forced out in 1898. Almost 50 years would pass before another Black would appear on an interracial club in organized baseball.

While integrated teams grew rare, several leagues allowed entry to all-Black squads. In 1889, the Middle States League included the New York Gorhams and the Cuban Giants, the most famous black team of the age. The Giants posted a 55–17 record. In 1890, the alliance reorganized as the Eastern Interstate League and again included the Cuban Giants. Giants’ star George Williams paced the circuit with a .391 batting average, while teammate Arthur Thomas slugged 26 doubles and 10 triples, both league-leading totals. The Eastern Interstate League folded in midseason, and in 1891 the Giants made one final minor league appearance in the Connecticut State League. When this circuit also disbanded, the brief entry of the Cuban Giants in organized baseball came to an end. In 1898, a team formed calling itself the Acme Colored Giants affiliated with Pennsylvania’s Iron and Oil League, but won only eight of 49 games before dropping out, marking an ignoble conclusion to these early experiments in interracial play.

[Baseball] should be taken seriously by the colored player. An honest effort of his great ability will open the avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand-in-hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games -- baseball.

Sol White

Overall, at least 70 Black people appeared in organized baseball in the late 19th century. About half played for all-Black teams, the remainder for integrated clubs. Few lasted more than one season with the same team. By the 1890s, the pattern for Black baseball that would prevail for the next half century had emerged. Black players were relegated to “colored” teams playing most of their games on the barnstorming circuit, outside of any organized league structure. While exhibition contests allowed them to pit their skills against whites, they remained on the outskirts of baseball’s mainstream, unheralded and unknown to most Americans.

As early as the 1880s and 1890s, several all-Black traveling squads had gained national reputations. The Cuban Giants, formed among the waiters of the Argyle Hotel to entertain guests in 1885, set the pattern and provided the recurrent nickname for these teams. Passing as Cubans, so as not to offend their white clientele, the Giants toured the East in a private railroad car playing amateur and professional opponents. In the 1890s, rivals like the Lincoln Giants from Nebraska, the Page Fence Giants from Michigan, and the Cuban X Giants in New York emerged. From the beginning these teams combined entertainment with their baseball to attract crowds. The Page Fence Giants, founded by Bud Fowler in 1895, would ride through the streets on bicycles to attract attention. In 1899, Fowler organized the All-American Black Tourists, who would arrive in full dress suits with opera hats and silk umbrellas. Their showmanship notwithstanding, the Black teams of the 1890s included some of the best players in the nation. The Page Fence Giants won 118 of 154 games in 1895, with two of their losses coming against the major league Cincinnati Reds.

During the early years of the 20th century many Black players still harbored hopes of regaining access to organized baseball. Sol White wrote in 1906 that baseball, “should be taken seriously by the colored player. An honest effort of his great ability will open the avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand-in-hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games -- baseball.” Rube Foster, the outstanding figure in black baseball from 1910–1926, stressed excellence because “we have to be ready when the time comes for integration.”

But even clandestine efforts to bring in Black players met a harsh fate. In 1901, Baltimore Orioles Manager John McGraw attempted to pass second baseman Charlie Grant of the Columbia Giants off as a Native American named Chief Tokohama, until Chicago White Sox President Charles Comiskey exposed the ruse. In 1911, the Cincinnati Reds raised Black hopes by signing two light-skinned Cubans, Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, prompting the New York Age to speculate, “Now that the first shock is over it would not be surprising to see a Cuban a few shades darker. . . breaking into the professional ranks . . . it would then be easier for colored players who are citizens of this country to get into fast company.” But the Reds rushed to certify that Marsans and Almeida were “genuine Caucasians,” and while light-skinned Cubans became a fixture in the majors, their darker brethren remained unwelcome. Over the years, tales circulated of United States Black players passing as Indians or Cubans, but no documented cases exist.