Masanori Murakami, the overlooked trailblazer

If it were up to his father,

"When I was still young, I already fell in love with baseball," Murakami said in a recent Zoom interview. "I would cut a bamboo stick and find a softball and try to play baseball to some extent."

But his father, Kiyoshi, didn't want him to be an athlete. He wanted Murakami to be a doctor. As the young pitcher got older, his father wanted him to quit the sport and devote himself entirely to his studies.

But Murakami was gifted, his left arm blessed with too much natural ability, and his love of the game was too deep. He simply couldn't quit, and his mother even helped keep his playing a secret. When Murakami was in his second year of middle school, though, his father found out. He headed to the school to have a conversation with his son's coach. Though we'll never know what was said in that meeting, the tone was anything but cordial.

"I thought your father was going to punch me in the face," Murakami's coach told him later.

But an understanding had been reached. As Robert K. Fitts wrote in Murakami's biography, "Mashi" (what American players would later call him after struggling to pronounce his given name), the pitcher could continue playing as long as he studied hard in school. Oh, and one other thing, too:

“If you want to be a ballplayer,” Kiyoshi told his son, “you will have to be the best in Japan.”

***

Getting to America

After starring in high school, he was drafted by the Nankai (now SoftBank) Hawks. But Murakami was unsure if he wanted to pursue professional athletics. He planned to attend Hosei University and pitch for their baseball team before going into the family business.

"Initially, my father wanted me to become a doctor, but my head is not so good," Murakami said with a laugh. "So, aside from that, my family was actually running a private post office at the time. The assumption was that I would become the head of the home business."

But Japanese teams were also interested in sending players to America as a kind of a sporting cultural exchange program. What could young players learn from working with U.S. coaches and playing the American style of baseball, and then bring back home? Hawks manager Kazuto Tsuruoka made Murakami an offer that he simply couldn't refuse: He would get to be one of the players the team sent to America.

It was expensive to go to America, costing roughly 30,000 yen, or "about one-and-a-half year's worth of paychecks for a high school student," Murakami noted. It was an inaccessible place to go for many Japanese citizens.

But there was something else that had caught Murakami's eye, too:

"Another reason was a TV show called 'Rawhide,'" Murakami joked. "It was very famous in Japan and a lot of people were tuning in to watch that. It didn't have to be baseball. I just really wanted to go over to America."

Murakami wasn't selected to go that first season, instead spending much of the 1963 season with the Hawks' Minor League team. He did make his NPB debut later that year, though. At the tender age of 19, Murakami appeared in three games, pitched two innings, struck out two and gave up one run. Not a bad start for a youngster.

Come the following season, Murakami -- along with teammates Hiroshi Takahashi and Tatsuhiko Tanaka -- would join the San Francisco Giants. The deal was meant to benefit both sides, with the Giants making a footprint in Japan and the Hawks picking up new knowledge and training techniques. There was also the option for the Giants to purchase any of the players for $10,000 each -- at least that's what the Giants thought.

That issue would come to play later.

In the states

When Murakami arrived at the Giants' Spring Training home in Arizona -- his translation book carried with him wherever he went -- he was in for some culture shock.

In Japan, players trained by pushing their bodies to the breaking point-- and sometimes beyond -- to not only improve their skills, but harden their spirits. With the Giants, Murakami was told to save himself and hold back. Players were simply rounding back into shape to be ready for Opening Day.

"I felt that practice was much lighter over in Major League Baseball and I did get a little bored sometimes," Murakami said. "I felt that I wasn't using my body and I wasn't fatiguing my body as much as I could have."

He also didn't realize he would be paid differently. In Japan, players are paid all 12 months, while in America players are only paid during the regular season. Murakami had brought $400 with him, but had already spent much of it on gifts for friends and family. He would have to tighten his belt. The money troubles didn't end there.

Impressed with Murakami, but not ready to put him on the big league roster, the Giants sent him, Takahashi and Tanaka to Fresno, their Class A affiliate (Takahashi and Tanaka were not as advanced as Murakami and would later be optioned to the Rookie League Twins Falls Giants). When they arrived in town and the Japanese-American coordinator never showed up to help, they checked into a hotel that cost the players about $30 a night. They were quickly running out of funds and didn't know where to go.

Murakami went to a nearby bank to exchange 20,000 yen, for what was then worth about $50.

"I got that $50 to keep the clothes on my back and just keep living," Murakami said.

After explaining their issues, they were directed to Fresno's Japantown, located about three miles from the ballpark. That's where some luck was in store. While walking around, Murakami met a third-generation Japanese-American man named Howard Saiki, who recognized the ballplayers from the newspaper.

"He offered to take us in and let us sleep in his house," Murakami said. "He was someone that I still to this day really appreciate and am thankful for."

While the transition to a new country was difficult, things were much smoother on the mound.

Murakami made his U.S. professional debut against the Santa Barbara Dodgers on April 24, 1964. With the Giants trailing by five, Murakami entered the game in the fifth and no-hit the Dodgers the rest of the way. A week later, he made his home debut in front of a crowd of 433. He not only stopped a rally in its tracks, but when third baseman Bob Powell made a diving catch to save a run, Murakami "then did something which is not seen in American baseball," the Fresno Bee Republican wrote. "He walked off the mound and halfway to third base thanked Powell for making the catch."

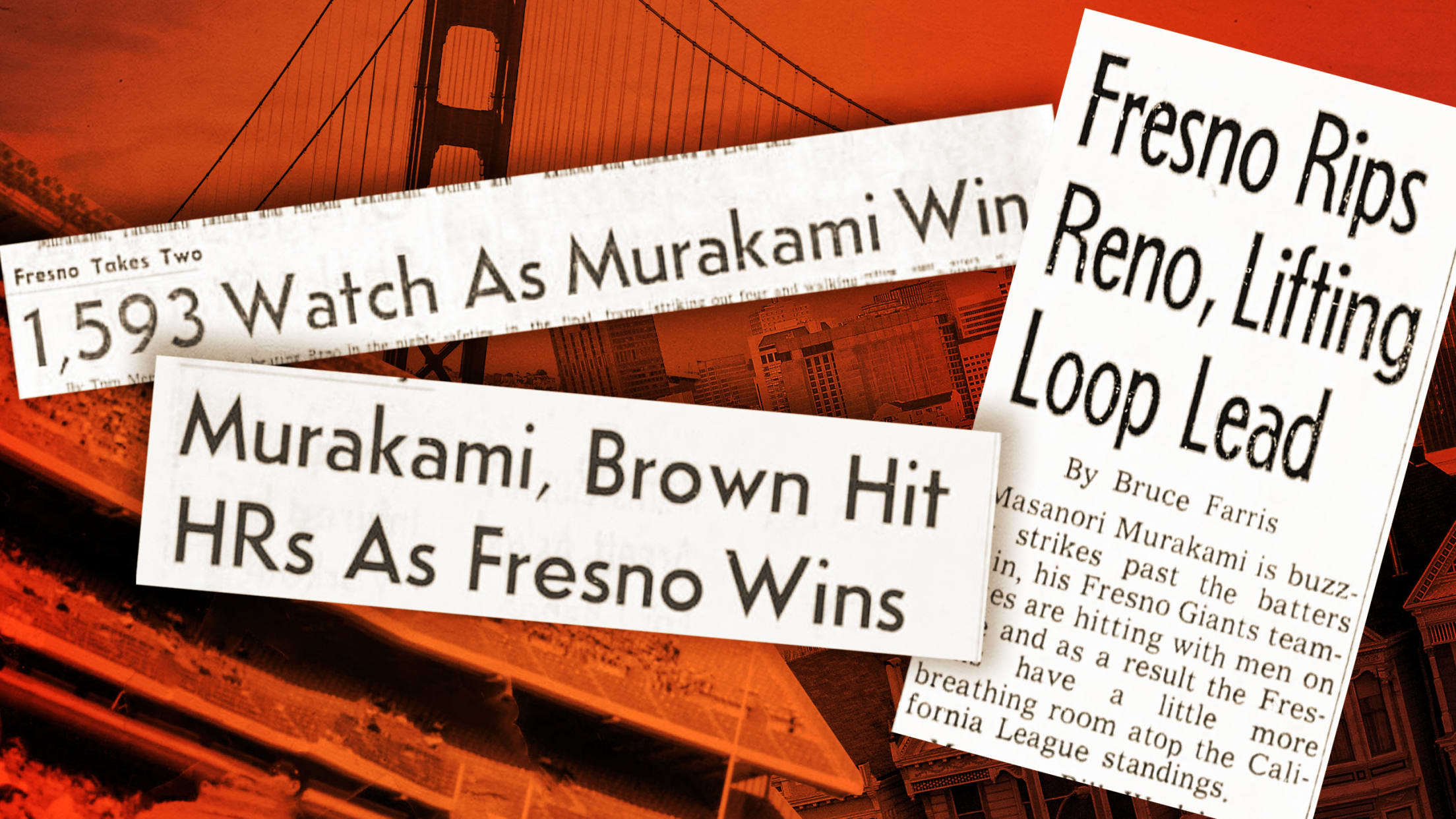

Just one month later, Murakami was already a celebrity in town. The team was in first place, Murakami was dominant and the fans couldn't get enough. The team held a Japanese American Day celebration on May 20, with Takahashi and Tanaka invited to take part. This time 1,593 fans passed through the turnstiles and the trio was presented plaques by the Fresno Nisei beauty queen, the mayor, and some of Fresno's most successful Japanese businessmen. Murakami made his first start of the year and got the victory after pitching seven innings of two-run ball, striking out 14 Reno batters.

He even topped his own legend on July 18, single-handedly delivering Fresno to victory over the San Jose Giants. After pitching two shutout innings, Murakami came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. He swung at Gary Meloy's first pitch and drove it deep into left field. It was nearly caught, but fortunately the wall was there: The ball and outfielder slammed against the fence at about the same time. As the ball rolled away, Murakami raced around the bases for a walk-off inside-the-park home run.

"Murakami was flying by the time he rounded second base," manager Bill Werle said, "and it would have taken a perfect relay for the play even to be close at home plate."

At the end of August, Murakami was clearly a star in the making. He had an 11-7 record, a 2.38 ERA and had struck out 159 batters in 106 innings en route to later earning the league's Rookie of the Year Award. With the Giants 6 1/2 games back in the National League, they wanted a bullpen upgrade for the final stretch. It was time to call Mashi to the Majors.

I still believe that I am the first -- and maybe the last person -- to ever hesitate or deny signing a contract when Major League Baseball was just at my fingertips.

Mashi Murakami

The big league debut

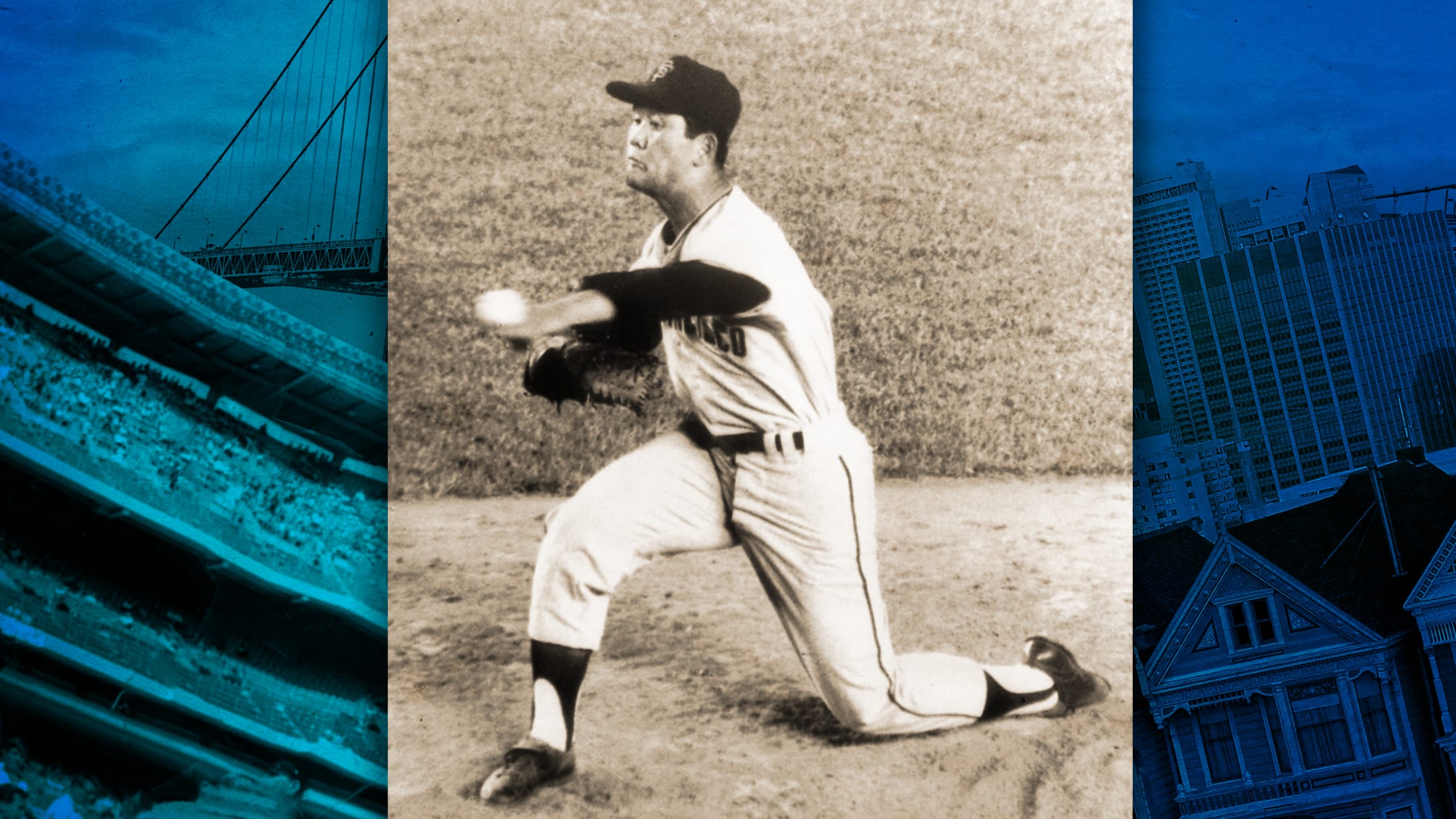

Beyond the numbers, team officials and reporters raved about his sneaky fastball, darting screwball and uncanny control, but his best weapon was his curveball.

"He has a big league curve right now and he's developing," Werle said.

It was time to put that hook to the test. But once again, the language barrier made things difficult for the young pitcher. He was flown to New York on Aug. 31, so he would be ready for the Giants' Sept. 1 game against the Mets. But when Murakami arrived at the hotel, there was no room waiting for him and he didn't know who to call.

"The hotel told me that my name wasn't listed and wasn't on the booking. I couldn't go into my room. I had nowhere to stay and I was thinking maybe I'll end up dead in the Hudson River tomorrow," Murakami joked. "Luckily, the traveling secretary found me and brought me to my room."

The problems didn't end there. When Murakami arrived at Shea Stadium, general manager Chub Feeney asked him to sign a new contract and officially join the team. Since he was already contracted to the organization, Murakami was wary of signing something new.

"My family and people in Japan told me to be careful with contracts because I didn't know how Japanese contracts worked -- and even worse how English contracts worked," Murakami said. "I was very reluctant to sign on the dotted line."

With the clock ticking and time running out, Feeney rushed to find a solution. After some frantic searching, the team found a Japanese speaker in the crowd who helped explain that Murakami needed to sign this new contract to officially join the Giants and be eligible to play. With about 15 minutes to go before first pitch, Murakami signed.

"I still believe that I am the first -- and maybe the last person -- to ever hesitate or deny signing a contract when Major League Baseball was just at my fingertips," Murakami said with a laugh.

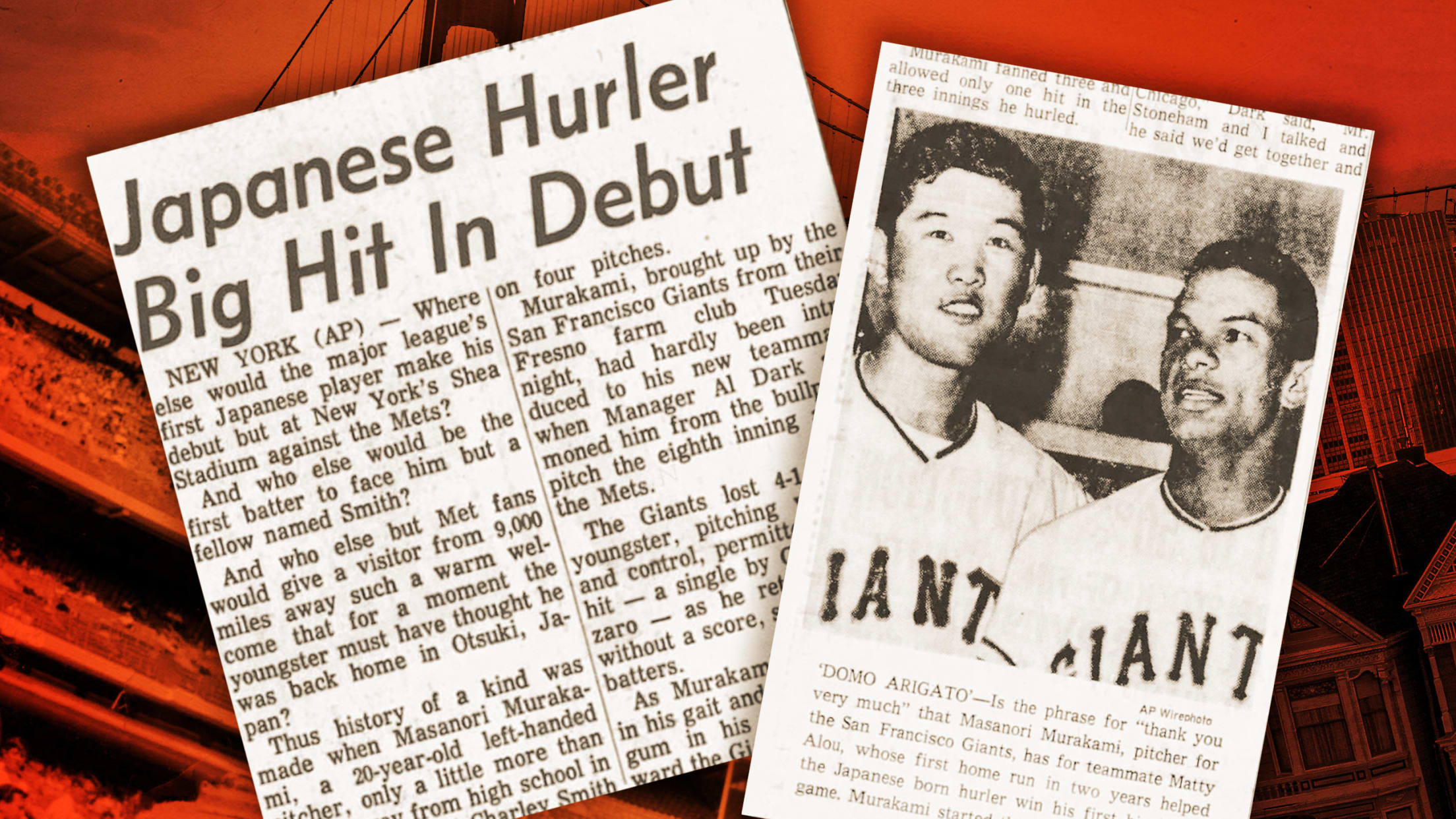

Given the stress of the day, you could understand if the Giants let Murakami sit in the bullpen and get used to the new digs. But with the Mets leading 4-0 heading into the bottom of the eighth, manager Alvin Dark called for the rookie southpaw.

The announcer called out "Mashi Murakami," and he ran onto the field with the roar of the crowd in his ears. Used to the 500-or-so fans that would attend Minor League games, hearing the nearly 40,000 cheering fans was an overwhelming experience.

"I was just focused on not getting tense, not getting nervous," Murakami said. "As I was walking from the bullpen, I was singing a very famous song called 'Sukiyaki' by Kyu Sakamoto. Just to keep my nerves down, I hummed the song all the way over to the mound."

Murakami went over the signs with catcher Del Crandall, then Charley Smith dug into the box. Murakami started his big league career with a fastball on the outside corner and soon got Smith to strike out looking. After giving up a single to Chris Cannizzaro, Murakami retired the next two batters to end the inning.

"Our dream has come true after thirty years of effort since the establishment of [Japanese] professional baseball," a reporter wrote in "Shukan Baseball." History had been made.

Murakami pulled off another achievement a few weeks later: His first big league win. On Sept. 29, Murakami was called in to pitch with San Francisco and Houston knotted at four in the ninth inning. Mashi tossed three shutout innings before Matty Alou hit his lone home run of the season in the bottom of the 11th to give the Giants the W.

“I felt like I was dreaming,” Murakami told Fitts. “I was waving at the fans in the stands without realizing it. It was not until I came back to the hotel that I realized I was the first Japanese [player] to win a Major League game. Once I thought about it, I could not stay calm. ‘I did it! I did it!’ I thought. I naturally picked up the phone and made an international call home. It was not a long moment, but it felt like hours until I reached Japan.”

Like in Fresno, Murakami quickly became a star in San Francisco. A fan club was quickly established and a local restaurant even added a Masanori Murakami cocktail to the menu.

The Giants were fans, too. After he had struck out 15 batters in 15 innings and posted a 1.80 ERA, they were looking forward to his presence in the bullpen the next season and so paid the $10,000 fee to the Hawks to secure his contract for the following season. The southpaw was excited and planned on staying in America over the winter to prepare. That excitement wouldn't last long.

The contract controversy

The Hawks had paid a $30,000 signing bonus to Murakami and were not prepared to lose a valued player for such a small fee. They argued that the $10,000 the Giants paid was a bonus for Murakami reaching the Major Leagues. They had Murakami write a letter stating that he was homesick, activating a clause that would allow him to return to Japan. They blamed Cappy Harada, who was employed by both teams and used as a liaison on the deal, for shady dealings. They argued that Murakami was a minor under Japanese law, so his parents' signature was necessary.

"When I returned to the Hawks in '64, the information I was being told from the Hawks was the complete opposite from what I was being told in the U.S.," Murakami said.

When Murakami was supposed to be reporting to the Giants for Spring Training at the end of January, he instead had signed a new contract with the Hawks. MLB Commissioner Ford Frick felt they had forced his hand.

"If in the face of documentary evidence there still is insistence on the part of the Hawks baseball team in going through with this new arrangement and the breaching of the original contract," Frick wrote, "then as Commissioner of Baseball I can only hold that all agreements, all understandings and all dealings and negotiations between Japanese and American baseball are canceled."

The window that Murakami had opened, the one that could have ushered in an era of open relations between the two leagues, was now effectively shut.

Finally, after months of cross-Pacific arguing, a compromise was struck: Murakami would return to the Giants for the 1965 season, but could return to Japan the following season and be placed on the voluntary retired list. That would have to be good enough, and Murakami was cleared to return.

His flight to San Francisco landed on May 4. He was back.

"It has happened so quickly," Giants publicist Gary Schumacher said. "We don't even know where he'll stay tonight. But we'll find him a room somewhere."

Back in the bigs

It was good timing. After all, Murakami's birthday was May 6 -- a date he shared with teammate and friend Willie Mays. There was a cake waiting for them at practice that day. His teammates were glad for his return.

“Murakami and I are good friends, so good that we may not need a language between us," Mays said.

Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry shared the sentiment. “He was, and is, one of the nicest guys you will ever meet," Perry told Fitts.

The offseason stress seemed to have an effect and Murakami carried a 9.31 ERA into June. But he quickly returned to form: From June 11 until the end of the year, Murakami posted a 2.92 ERA and struck out 77 batters in just 64 2/3 innings. He saved eight games, including closing out the infamous game when Juan Marichal clubbed Johnny Roseboro in the head with his bat. He gave up a home run to Pete Rose, who later tried to intimidate the pitcher by showing him his muscles. And, on Aug. 15, before the Giants took on the Phillies, the team celebrated Masanori Murakami Day.

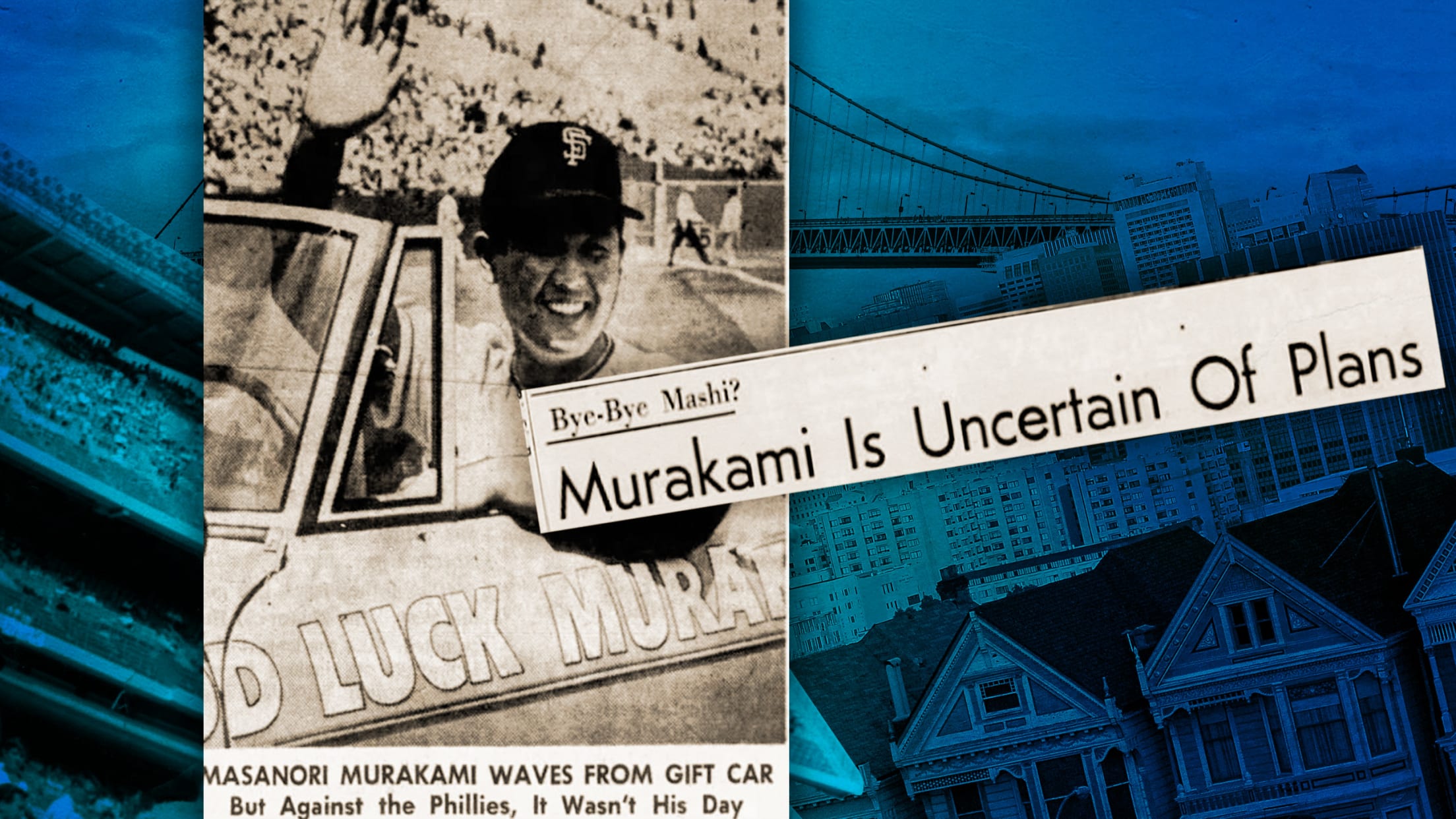

That day, 1,200 Japanese Americans were among the 27,000 fans who pushed their way through the gates to honor Murakami's achievement. Plaques were presented to Murakami before the game, messages from San Francisco's mayor and California's governor were relayed and Japanese consul general Tsutomu Wada gave a short speech. The pitcher even received a sports car from the soy sauce company, Kikkoman International. It was initially supposed to be a Ford Mustang, but was switched out at the last minute with a Datsun to show off a Japanese brand. It read, "Good luck Murakami" on the side.

Unfortunately, that's where the highlights ended as Murakami was given his first and only big league start. Perhaps overwhelmed with all the attention, he wasn't his usual sharp self. He stranded two runners in the first and pitched a 1-2-3 second, but failed to make it out of the third. A walk, a single and then a triple by Dick Allen ended Murakami's day en route to a 15-9 loss to the Phillies.

Murakami also had one of the strangest experiences in big league history. With the Giants leading the Reds, 18-5, on Aug. 5, Frank Robinson's turn in the order came up. He refused to get in the box.

"His name was called, but he wouldn't step out from the bench. It took some time, so I could hear the ump telling him to come out and they were just jabbering at each other and nothing happened. After a while, the ump told me to pitch without a batter in the box," Murakami said. "That was a very strange time and I felt more pressure having to pitch there because I was afraid of not being able to throw a strike without a batter in the box.

"Luckily, I did get a strikeout. I'll be honest, I don't remember if Frank Robinson ended up entering the box for that third strike but I do believe the umpire just waved him off and it was a strike recorded against no one in the batting box," Murakami said. "And in [my career], I threw 89 1/3 innings and recorded 100 Ks -- including that one magical strikeout."

The return to Japan

Unfortunately for the Giants, they finished the year in second place, just two games behind the Dodgers for the NL pennant. We can only imagine what would have happened if Murakami pitched the full season with the team. Perhaps he wouldn't have had that cold month and maybe he could have been the difference between a pennant and a long offseason.

Though he was expected back in Japan, Murakami hoped to return to San Francisco the following year. It looked like that could be possible when Tsuruoka announced his retirement from the Hawks. But when the newly appointed manager, Kazuo Kageyama, died of a heart attack in November, Tsuruoka returned to take over the club. That sealed Murakami's decision. Feeling he owed something to his manager, Murakami returned to Japan.

"Mr. Tsuruoka was the one who promised me a ticket to the United States when I first joined the team, and he kept his word there," Murakami said. "So, I wanted to make sure I kept my word when I told him I was returning in '65. ... Truth be told, my heart was with continuing to play in the U.S., but for the sake of keeping my word with Mr. Tsuruoka, I came back. The way things turned out was unfortunate, but I do have pride that I kept my promise and I didn't go back on my word."

He would pitch in the NPB for the next 16 years, hanging up his cleats in 1982, having put together a lifetime record of 103-82 with a 3.64 ERA. He had moments of dominance, including going 18-4 with a 2.38 ERA in 1968, but it was impossible to ever live up to the larger-than-life legend that he created by being the first Japanese player in the Major Leagues.

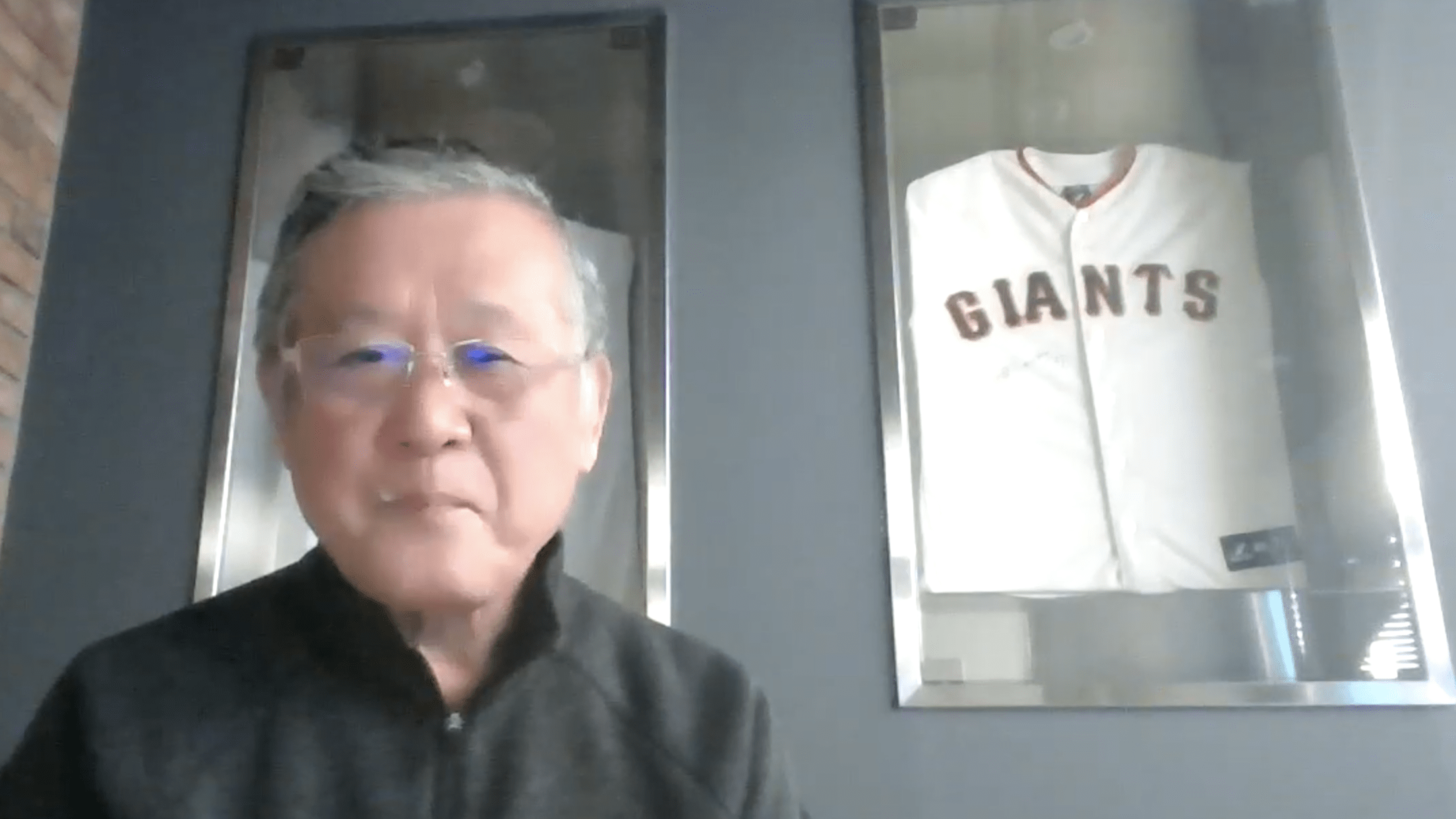

After retiring, he stayed around the game. He worked as a commentator, a sportswriter, a pitching coach and a scout for the Giants. He remains connected to the game to this day and regularly communicates with the Giants. He was honored in 2008 with a bobblehead and threw out the first pitch on the 50th anniversary of his debut during the 2014 Japan Series. He is engaged in charity and community service events, including an annual charity golf tournament -- something that was inspired by Roberto Clemente.

The two had first met one day in Pittsburgh when Murakami was cooling off outside the clubhouse. Clemente introduced himself and then quickly asked, "Who's better? Me or Willie Mays?"

Mays was Murakami's teammate and was in the middle of his 52 home run, MVP-Award winning season. So, Murakami's answer was simple: Mays. This upset Clemente, who gave Murakami a "very angry look," but the young pitcher also had a request for the star. He asked Clemente to wait a moment and he raced into the clubhouse to retrieve one of his shikishi boards, a special extra-thick Japanese paper made especially for autographs.

"As he was signing his autograph, he was telling me about charity work and just giving back to the community," Murakami said. "That was something that stuck with me for a long time."

Those words came back to him in 1995, the year that Hideo Nomo debuted with the Dodgers and ended the 30-year gap without a Japanese big leaguer since Murakami's final appearance.

"I remembered his words and I remembered a lot of things that he had been doing," Murakami said. "I decided to start giving back to the community on my own. I started activities that contributed to the Special Olympics and to U.N.-related charities. I've been continuing that since then."

Though Murakami may wish that his career turned out another way, he's proud of his accomplishments and his place in history.

"How I look at it now is that you only live once," Murakami said. "Players that want to go from Japan and challenge themselves at the highest level should be going and there's a chance you don't succeed. There's a chance that you'll fail and you don't make it to the Major Leagues, but it's your life and you should be challenging yourself. ... It's going to become a page in that person's life and an experience that will live with them forever."

Special thanks to Sami Kawakami for helping arrange my conversation with Murakami and to Sho Kurematsu for translation assistance. All errors are mine. Robert Fitts' book, "Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer," was also an invaluable resource for this story.