History of Black Baseball, Part V

The desegregation of organized baseball opened the way not only to Black players in the United States but to those in other parts of the Americas as well. Throughout the 20th century, baseball had imposed a curious double standard on Latin players, accepting those with light complexions but rejecting their darker countrymen. With the color barrier down, Major League clubs found a wealth of talent in the Caribbean. Minnie Miñoso, the “Cuban Comet” who integrated the Chicago White Sox, became the first of the great Latin stars. Over a 15-year career, Miñoso compiled a .298 batting average. In 1954, slick-fielding Puerto Rican Vic Power launched his career with the Athletics.

• History of Black Baseball, Part I

• History of Black Baseball, Part II

• History of Black Baseball, Part III

• History of Black Baseball, Part IV

The following year, Roberto Clemente, the greatest of the Latin stars, debuted with the Pittsburgh Pirates. The proud Puerto Rican won four batting championships and amassed 3,000 hits en route to a .317 lifetime batting average. In the late 1950s, the San Francisco Giants revealed the previously ignored treasure trove that existed in the Dominican Republic. In 1958, Felipe Alou became the first of three Alou brothers to play for the Giants, and in 1960 the Giants unveiled pitcher Juan Marichal, “the Dominican Dandy,” who won 243 games en route to the Hall of Fame.

Among the early Latin players were two sons of stars of the Jim Crow age. Perucho Cepeda, who had won renown as “The Bull” in his native Puerto Rico, had refused to play in the segregated Negro Leagues. His son Orlando, dubbed “The Baby Bull,” went on to star for the Giants and Cardinals. Luis Tiant, Sr., a standout performer in both Cuba and the Negro Leagues, lived to see Luis, Jr. win over 200 Major League games and excel in the 1975 World Series.

As the Major Leagues moved slowly toward complete desegregation, throughout the nation Black players invaded the Minor Leagues. In the Northern and Western states, these athletes, a combination of youthful prospects and Negro League veterans, were greeted by a storm of insults, beanballs and discrimination. “I learned more names than I thought we had,” states Piper Davis of his treatment by fans in the Pacific Coast League. At least a half-dozen Black players had to be carried off the field on stretchers after being hit by pitches between 1949 and 1951. In city after city, Black ballplayers found hotels and restaurants unwilling to serve them. “At the same time when they signed Blacks and Latins,” argues John Roseboro about his Dodger employers, “they should have made sure they would be welcome.” But neither the Dodgers nor other clubs provided any special assistance for their Black farmhands.

Despite these conditions, Black players compiled remarkable records in league after league. In the early 1950s, they overcame adversity and dominated the lists of batting leaders at the Triple-A level and in many of the lower circuits as well.

In 1952, Black players began to appear on Minor League clubs in the Jim Crow South. The Dallas Eagles of the Texas League, hoping to boost sagging attendance, signed former Homestead Gray pitcher Dave Hoskins to become the “Jackie Robinson of the Texas League.” Hoskins took the Lone Star State by storm, attracting record crowds en route to a 22–10 record. The Black pitcher posted a 2.12 earned run average and also finished third in the league in batting with a .328 mark. By 1955, every Texas League club except Shreveport fielded Black players.

Hoskins’ performance inspired other teams throughout the South to scramble for Black players. In 1953, 19-year-old Henry Aaron desegregated the South Atlantic League, which included clubs in Florida, Atlanta, and Georgia, while Bill White appeared in the Carolina League. Playing for Jacksonville (a city which seven years earlier had barred Jackie Robinson), Aaron “led the league in everything but hotel accommodations.” By 1954, when the United States Supreme Court issued its historic Brown v. Board of Education decision ordering school desegregation, Black players had appeared in most Southern minor leagues.

The integration of the South, however, did not proceed without incidents. Black players recall these years as “an ordeal” or a “sentence” and described the South as “enemy country” or a “hellhole.” In 1953, the Cotton States League barred brothers Jim and Leander Tugerson from competing. The following year, Nat Peeples broke the color line in the Southern Association, but lasted only two weeks. For the remainder of the decade, the league adhered to a whites-only policy, a strategy which contributed to the collapse of the Southern Association in 1961. As resistance to the civil rights movement mounted in the 1950s, Black players found themselves in increasingly hostile territory. Even in the pioneering Texas League, teams visiting Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1956 had to leave their Black players at home due to stricter segregation laws.

In the face of these obstacles, young Black stars like Aaron, Curt Flood, Frank Robinson, Bill White, and Leon Wagner overcame their frustrations “by taking it out on the ball.” “What had started as a chance to test my baseball ability in a professional setting,” wrote Curt Flood, “had become an obligation to test myself as a man.” Throughout the 1950s, Black players appeared regularly among the league leaders of the Texas, South Atlantic, Carolina, and other circuits, advancing both their own careers and the cause of integration.

As these events unfolded in the South, the Major Leagues completed their long overdue integration process. In 1955, the Yankees, after denying charges of racism for almost a decade, finally promoted Elston Howard to the parent club. Two more years passed before the Phillies integrated, and not until 1958 did a Black player don a Tiger uniform. Thus, at the start of the 1959 season, only the Boston Red Sox, who had yet to hire either Black scouts or representatives in the Caribbean, retained their Jim Crow heritage. A storm of protest arose when the Red Sox cut Black infielder Elijah “Pumpsie” Green just before Opening Day, but on July 21, 1959, 12 years and 107 days after Jackie Robinson’s Dodger debut, Green won promotion to the Boston club, completing the cycle of Major League integration.

While integration became a reality in organized baseball, the Negro Leagues gradually faded into oblivion. As early as 1947, Negro League attendance, especially in cities close to National League parks, dropped precipitously. “People wanted to go Brooklynites,” recalls Monarch pitcher Hilton Smith. “Even if we were playing here in Kansas City, people wanted to go over to St. Louis to see Jackie.” Negro League owners hoped to offset declining attendance by selling players to organized baseball, but Major League teams paid what Effa Manley called “bargain basement” prices for All-Star talent. In 1948, the Manleys’ Newark Eagles and New York Black Yankees disbanded. The Homestead Grays severed all league connections and returned to its roots as a barnstorming unit. Without these teams, the Negro National League collapsed. A reorganized 10-team Negro American League, most of whose franchises were located in minor league cities, vowed to go on, but the spread of integration quickly thinned its ranks. By 1951, the league had dwindled to six teams. Two years later, only the Birmingham Black Barons, Memphis Red Sox, Kansas City Monarchs and Indianapolis Clowns remained.

For several years in the early 1950s, the Negro Leagues remained a breeding ground for young Black talent. The New York Giants plucked Willie Mays from the roster of the Birmingham Black Barons, while the Boston Braves discovered Hank Aaron on the Indianapolis Clowns. The Kansas City Monarchs produced more than two dozen Major Leaguers, including Robinson, Paige, Banks, and Howard. But for most Black players, the demise of the Negro Leagues had disastrous effects. “The livelihoods, the careers, the families of 400 Negro ballplayers are in jeopardy,” complained Effa Manley in 1948, “because four players were successful in getting into the Major Leagues.” The slow pace of integration left most in a state of limbo: set adrift by their former teams, but still unwelcomed in organized baseball. Some players like Buck Leonard and Cool Papa Bell were too old to be considered, while others like Ray Dandridge and Piper Davis found themselves relegated to the Minor Leagues, where outstanding records failed to win them promotion.

Throughout the 1950s the Negro American League struggled to survive, recruiting teenagers and second-rate talent for the modest four-team loop. In 1963, Kansas City hosted the 30th and last East-West All-Star Game and the following year the famed Monarchs ceased touring the nation. By 1965, the Indianapolis Clowns remained as a last vestige of Jim Crow baseball. Utilizing white as well as Black players, the Clowns continued for another decade. “We are all show now,” explained their owner. “We clown, clown, clown.”

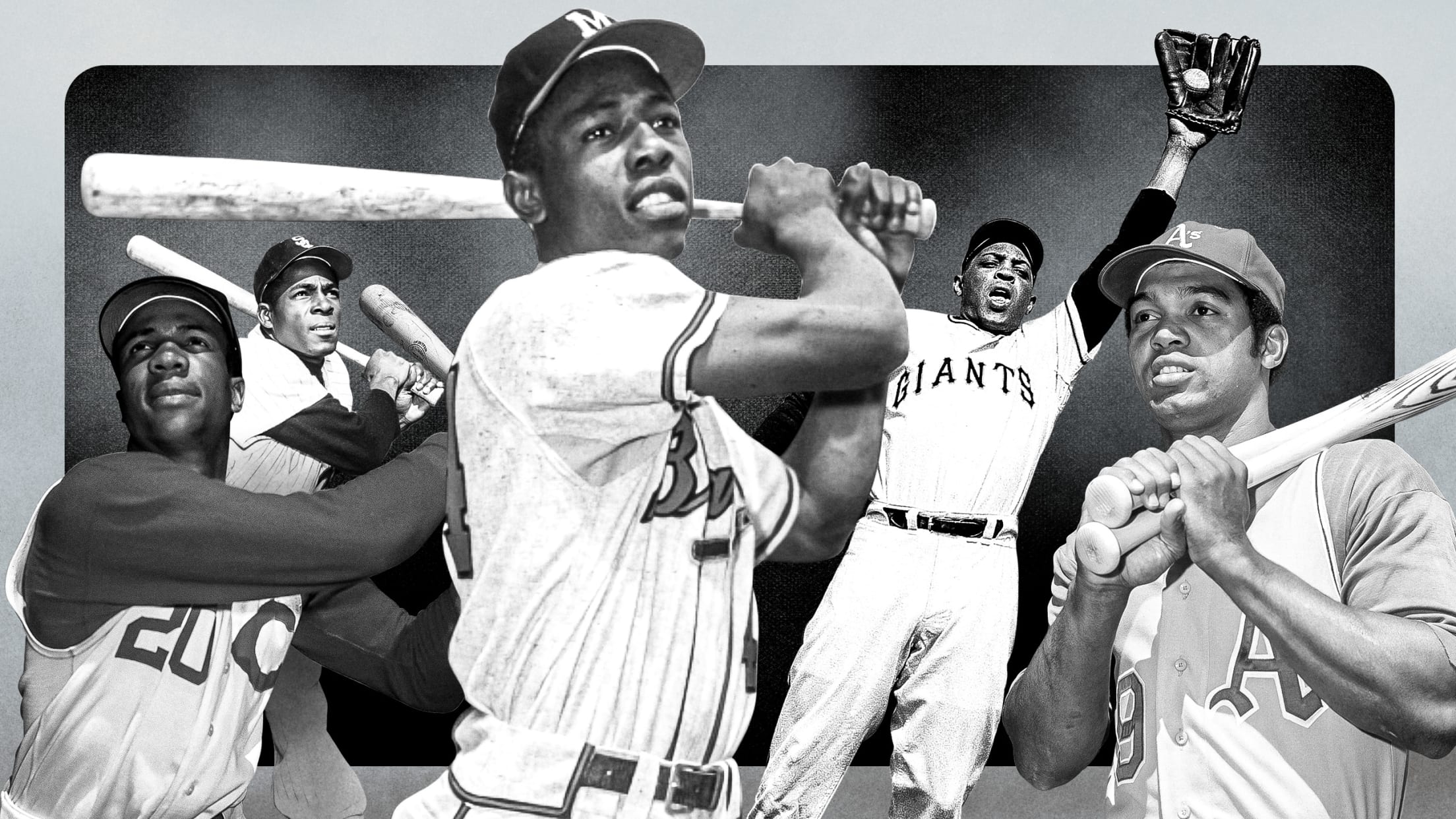

But the legacy of the Negro Leagues remained. Robinson and other early Black players introduced new elements of speed and “tricky baseball” into the Major Leagues, transforming and improving the quality of play. Since 1947, Black players have led the National League in stolen bases in all but two seasons. In the American League, a Black or Latin baserunner has topped the league every year since 1951 with only two exceptions. Nor did this injection of speed come at the expense of power. In the 1950s and 1960s, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Frank Robinson reigned as the greatest power hitters in baseball. Thus, by the 1960s, the national pastime more closely resembled the well-balanced offensive structure of the Negro Leagues than the one-dimensional power-oriented attack that had typified the all-white Majors.

The demise of the Negro Leagues and the decline of segregation in the Majors, however, did not end discrimination. Conditions on and off the field, in Spring Training and in the executive suites, repeatedly reminded the Black athletes of their second-class status. In the early 1950s, all-white teams taunted their Black opponents with racial insults. Black players like Jackie and Frank Robinson, Minnie Miñoso and Luke Easter repeatedly appeared among the league leaders in being hit by pitches. While Black superstars like Willie Mays had little difficulty ascending to the Major Leagues, players of only slightly above average talent found themselves buried for years in the Minors. Many observers charged that teams had imposed quotas on the number of Blacks they would field at one time.

In cities like St. Louis, Washington, D.C., and, later, Baltimore, Black ballplayers could not stay at hotels with their teammates. In 1954, they achieved a breakthrough of sorts when the luxury Chase Hotel in St. Louis informed Jackie Robinson and other Dodger players that they could room there, but had to refrain from using the dining room or swimming pool or loitering in the lobby. Ten years later, the hotel had removed these restrictions, but still relegated Black players, according to Hank Aaron, to rooms “looking out over some old building or some green pastures or a blank wall, so nobody can see us through a window.”

Black players faced even greater discrimination each year in Spring Training in Florida. While all Spring Training sites now accepted Black people, segregation statutes and local traditions forced them to live in all-Black boarding houses far from the luxury air-conditioned hotels which accommodated white players. “The whole set-up is wrong,” protested Jackie Robinson. “There is no reason why we shouldn’t be able to live with our teammates.” When teams traveled from place to place, Black ballplayers could not join their fellow teammates in restaurants. Instead they had to wait on the bus until someone brought their food out to them.

Some teams attempted to reduce the problems faced by Black players. Several clubs moved to Arizona, where conditions were only moderately improved. The Dodgers built a special Spring Training camp at Vero Beach where players could live together. Most organizations, however, did very little to assist their Black employees.

By the time that Jackie Robinson retired in 1956, conditions had barely improved. “After 10 years of traveling in the South,” he charged, “I don’t think advances have been fast enough. It’s my belief that baseball itself hasn’t done all it can to remedy the problems faced by ... players.” Over the next decade, a new generation of Black players militantly demanded change. Cardinal stars Bill White, Curt Flood, and Bob Gibson protested against conditions in St. Petersburg, while Aaron and other Black Braves demanded changes in Bradenton. In many instances, however, significant changes awaited passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 barring segregation in public facilities.

By 1960, Robinson, Campanella, Doby, and the cadre of Negro League veterans who had formed the vanguard of baseball integration had retired. In their wake, a second generation of Black players, most of whom had never appeared in the Negro Leagues, made most Americans forget that Jim Crow baseball had ever existed, as they shattered longstanding “unbreakable” records. In 1962, Black shortstop Maury Wills stole 104 bases, eclipsing Ty Cobb’s 47-year-old stolen base mark. Twelve years later, outfielder Lou Brock stole 118 bases en route to breaking Cobb’s career stolen-base record as well.

In 1966, Frank Robinson, who had won the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1961, became the first player to win that honor in both leagues when he led the Baltimore Orioles to the American League pennant. By the end of his career, Robinson had slugged 586 home runs; only Babe Ruth among players of the Jim Crow era had hit more. Both Ernie Banks and Willie McCovey also amassed more than 500 home runs during this era. On the pitcher’s mound, the indomitable Bob Gibson proved himself one of the greatest strikeout pitchers in the game’s history. Upon retirement, Gibson had amassed more strikeouts than anyone except Walter Johnson. Brock, Frank Robinson, Banks, McCovey, and Gibson all won election to the Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility.

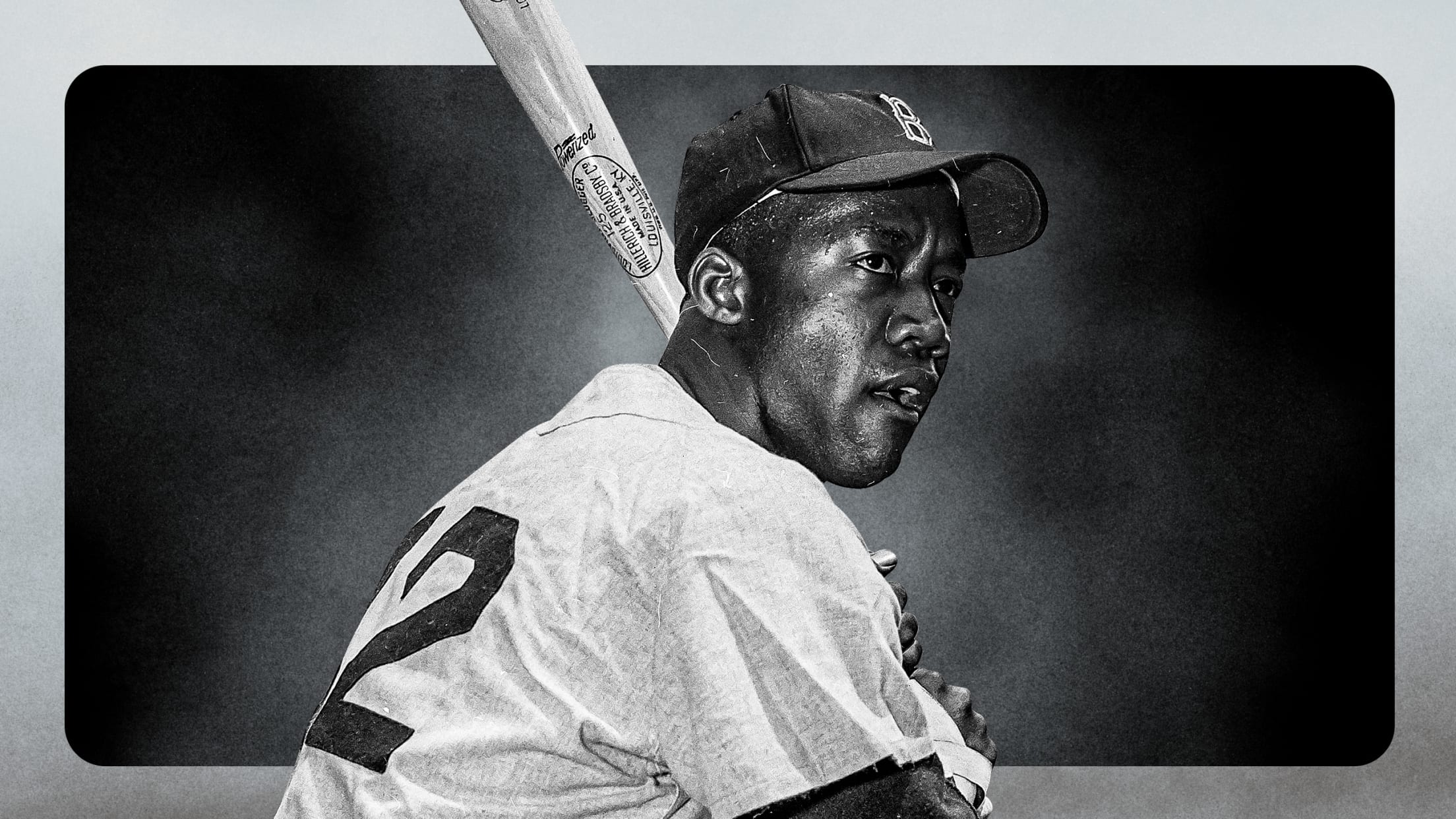

The greatness of these players notwithstanding, two other Black players, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, both of whom ironically had begun their careers in the Negro Leagues, reigned as the dominant stars of baseball in the 1950s and 1960s. Originally signed by the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League, Mays had joined the New York Giants midseason in 1951, sparking their triumph in the most famous pennant race in history and winning the Rookie of the Year Award. After two years in the military, he returned in 1954 to bat a league-leading .345 and hit 41 home runs. The following year, he pounded 51 homers. A spectacular center fielder, Mays won widespread acclaim as the greatest all-around player in the history of the game. In 1969, he became only the second player in Major League history to hit 600 home runs and took aim at Babe Ruth’s legendary lifetime total of 714. Over the next four seasons, the aging Mays added 60 more homers before retiring short of Ruth’s record.

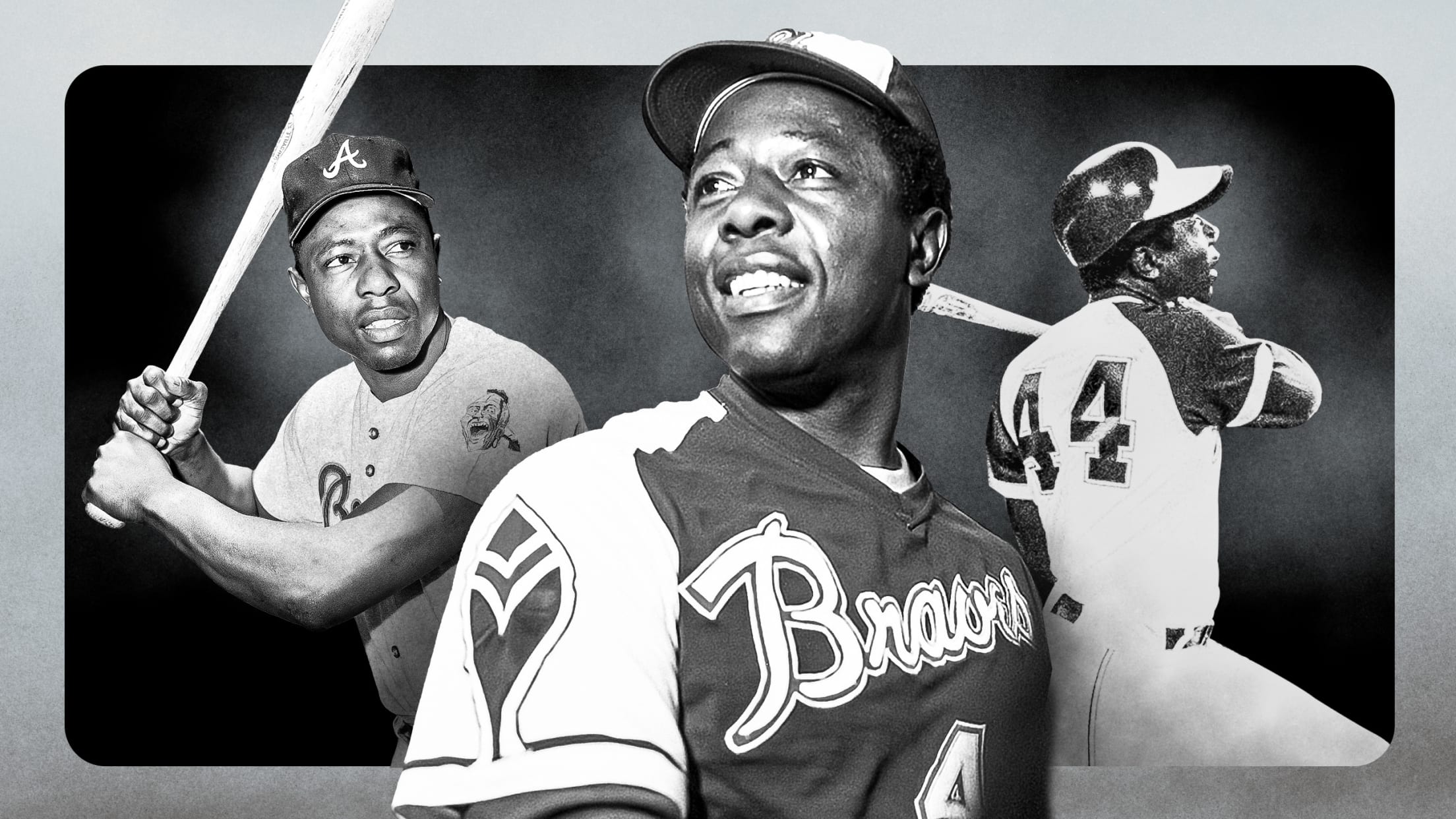

Unlike Mays, who had begun his career amidst the glare of the New York media, Hank Aaron had spent his career first in Milwaukee and later in Atlanta, far distant from the center of national publicity. Nonetheless, he steadily compiled record-threatening statistics in almost every offensive category. In 1972, at age 38, he surpassed Mays’ home run total and set his sights on Ruth. Entering the 1973 season, he needed just 41 home runs to catch the Babe. Performing under tremendous pressure and fanfare, Aaron stroked 40 homers, leaving him just one shy of the record. He tied Ruth’s mark with his first swing of the 1974 season. Three days later, on April 8, 1974, a nationwide television audience watched Aaron stroke home run number 715. Babe Ruth’s “unreachable” record thus fell to a man whose career had started with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues.

When Aaron retired in 1976, he boasted 755 home runs and held Major League records for games played, at-bats, runs batted in and extra-base hits. He also ranked second to Ty Cobb in hits and runs scored.

By the 1970s, Black players had become an accepted part of the baseball scene and regularly ranked among the most well-known symbols of the sport. Reggie Jackson, Willie Stargell, and Joe Morgan had succeeded Aaron, Mays, and the Robinsons as Hall of Fame caliber superstars. Yet three decades after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier, racism and discrimination remained a persistent problem for baseball. Several studies demonstrated that baseball management channeled Black people into positions thought to require less thinking and fewer leadership qualities. In 1968, Black players accounted for more than half of the Major League outfielders, but only 20 percent of other position players. Black catchers were rare, and fewer than one in 10 pitchers were Black. By 1986, the disparity had grown greater. American-born Black people comprised 70 percent of all outfield positions but only 7 percent of all pitcher, second basemen, and third basemen positions. There were no American-born Black catchers in the Major Leagues at the start of the 1986 season.

While superior Black players had open access to the Major Leagues, those of average or slightly above average skills often found their paths blocked. “The Negro player may have to be better qualified than a white player to win the same position,” argued Aaron Rosenblatt in 1967. “The undistinguished Negro player is less likely to play in the Major Leagues than the equally undistinguished white player.” Rosenblatt demonstrated that Black Major Leaguers on the whole batted 20 points higher than whites. As batting averages dropped, so did the proportion of Black players. This trend continued into the 1980s. A 1982 study revealed that 70 percent of all Black non-pitchers were everyday starters, indicating a substantial bias against Black ballplayers who filled utility or pinch-hitting roles. Statistics compiled in 1986 showed a strikingly similar pattern.

The subtle nature of this on-the-field discrimination obscured it from public controversy. The failure of baseball to provide jobs for Black people in managerial and front office positions, however, became an increasing embarrassment. In the early years of integration, baseball executives bypassed the substantial pool of experienced Negro Leaguers from consideration for managerial and coaching positions. A handful of Black coaches, including Sam Bankhead, Nate Moreland, Marvin Williams, and Chet Brewer managed independent, predominantly all-Black teams in the Minor Leagues. The first generation of Black Major Leaguers fared no better. “We bring dollars into club treasuries when we play,” exclaimed Larry Doby, “but when we stop playing, our dollars stop.” No Major League organization hired a Black managed at any level until 1961 when the Pittsburgh Pirates placed Gene Baker at the helm of their Batavia franchise. By the mid-1960s no Black coaches had managed in the Majors and only two had held full-time Major League coaching positions. The first Black umpire did not appear in the Majors until 1966, when Emmett Ashford appeared in the American League.

In the final years of his life, Jackie Robinson made repeated pleas for baseball to eliminate these lingering vestiges of Jim Crow. “I’d like to live to see a Black manager,” he stated before a national television audience at the 1972 World Series. Nine days later he died, his dream unfulfilled. In 1975, the Cleveland Indians hired Frank Robinson to be the first Black Major League manager. This precedent, however, opened few new doors. Robinson lasted two-and-a-half seasons with the Indians, later managed the San Francisco Giants for four years, and in 1988 was made manager of the Baltimore Orioles. Maury Wills and Larry Doby each had brief half-season stints as managers. After four decades of integration, only these three men had received Major League managerial opportunities.

A similar situation existed in Major League front offices. Only one Black man, Bill Lucas of the Atlanta Braves, had served as a general manager. As late as 1982, a survey of 24 clubs (the Yankees and Red Sox refused to provide information) found that of 913 available white-collar baseball jobs, Black people held just 32 positions. Among 568 full-time Major League scouts, only 15 were Black. While many teams hired former players as announcers, few employed Black players in these roles. Five years later, conditions had not improved. Of the top 879 administrative positions in baseball only 17 were filled by Black people and 15 by Hispanics. Four teams in California — the Dodgers, Giants, Athletics, and Angels — accounted for almost two-thirds of the minority hiring. Ten out of 14 American League teams, and five of 12 National League franchises had no Black people in management positions.

These shortcomings came to haunt baseball in 1987. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth had dedicated the season to the commemoration of the 40th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s Major League debut. As the celebration began, Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Al Campanis, who had played with Robinson at Montreal, appeared on ABC-TV’s Nightline. When asked about the dearth of Black managers, Campanis explained that Black people, “may not have some of the necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager or general manager.”

Campanis’ statement, which surely reflected the thinking of many baseball executives, evoked a storm of protest, and precipitated his resignation. An embarrassed Ueberroth pledged to take action to bring more Black people into leadership positions and hired University of California sociologist Harry Edwards to facilitate the process. Fifty Black players and Latinos with past or present connections to baseball created their own Minority Baseball Network to apprise Black people of employment opportunities and to lobby clubs to recruit more minorities for front office jobs.

When the controversy of 1987 had subsided, few franchises had taken significant steps to increase minority hiring. Several clubs added Black employees to administrative positions, but none offered field or general manager positions to nonwhite candidates. In 1988, Frank Robinson received his third chance to manage in the Major Leagues, this time with the Baltimore Orioles. At midseason 1989 Cito Gaston assumed the reins of the Toronto Blue Jays. When the squads managed by Robinson and Gaston had their initial confrontation, it marked, after 40 years of integration, the first time that two teams managed by Black men had competed in a Major League game. Fittingly, on the final weekend of the season, the Orioles and Blue Jays met face-to-face in a series to decide the championship of the American League Eastern Division. The spectacle offered a resounding rebuke to the shortsightedness and persistent discrimination that continues to plague the national pastime.