Baylor overcame obstacles off the field

Former AL MVP Award winner shares memories of growing up in segregated Texas

DENVER -- In many ways, Don Baylor was surrounded by love in segregated Austin, Texas, in the early 1960s. But it takes more than love to make things right. And what was right for Baylor was joining two other students to integrate O. Henry Junior High as a seventh-grader.

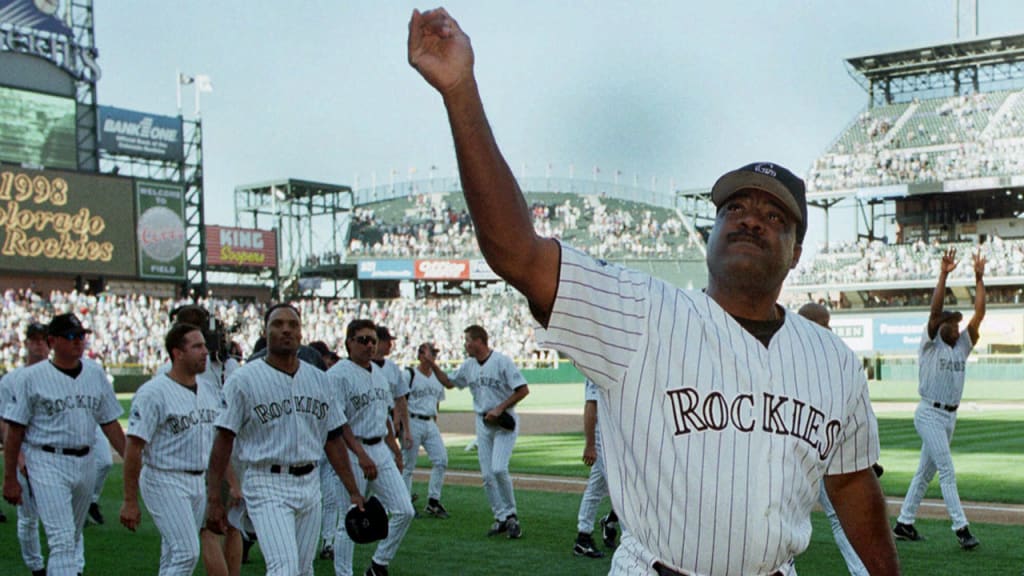

It was this act, even more than a lengthy career that included the 1979 American League Most Valuable Player Award, more than a long career of coaching and managerial stints with the Rockies (1993-98) and Cubs (2000-02), that bring the focus to Baylor, 67, as MLB.com celebrates Black History Month.

The Baylors lived in the Clarksville section, an-African American community populated by the low-wage employees at the State Capitol, or those who worked as domestics for the families of the elite. But by fifth grade, the nearby schools were for white students.

So Baylor and any other students in the neighborhood had to take a bus -- 5 cents, plus a 2-cent transfer each way. It meant he had to wake up early, and at the end of the day at a school called Blackshear, it meant he needed to sprint downhill. Or else he would miss that bus, run and end up not getting home until about 6 p.m.

At least he had people looking out for him along the way.

"My aunt was a teacher at the school," Baylor said by phone. "I can remember my grandfather, my dad's dad, never drove but was on the other side of 6th and Congress. He worked at the same place for 50 years, and when we made the transfer, I would see him all the time.

"We were guarded -- everybody took care of everybody's kids. There were not many phones in the neighborhood, but my grandmother had one. She would pick up a rock and throw it on top of our tin-roof house. My grandmother was a pitcher way back then."

Still, the idea of walking a mile and a half to O. Henry Junior High -- even if he was stepping into a different world -- made more sense than bus transfers. And it was time.

According to the Austin History Center, in 1958, 14-year-old Sandra Kay Hall became the first African-American to attend a white school, Allan Junior High, but it wasn't universal. In 1961-62, Baylor's parents -- mother, Lillian, who worked as a cafeteria supervisor at a white high school, and father, George, a baggage handler for Missouri Pacific Railroad -- let him choose his junior high. Baylor and two friends, Lenore Higgins and Lewis Chambers, decided they would attend O. Henry, which served an affluent community.

"I don't even know if at that age I was even thinking about the kind of abuse you were going to take as a seventh-grader," Baylor said. "That was, I guess, a bold move at the time."

Knowing the atmosphere he was entering, Baylor said he started a paper route so that he could afford a nice pair of jeans. But denim is not armor.

The three friends were often not allowed to attend classes together, which furthered the isolation. And the fact he was in a different world struck Baylor upside the head, literally.

"I had one teacher ask me where the 38th parallel was," Baylor said. "I was scared to death to even answer. He whacked me over the top of the head with a book and said, 'Well, you'll know where it is tomorrow.'"

"The students were going to drop the 'N' word on you because that's all they knew, you know? It was really more the teachers than the students."

An often-told part of the Jackie Robinson story was Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey urging him to have "the courage to not fight back." What isn't as emphasized is that was a three-year agreement. Once released from those shackles, Robinson unleashed a rage that he carried onto the field -- and became an outspoken critic of ill treatment.

While at O. Henry, Baylor felt a conflict familiar to many who dealt with hostility while breaking racial barriers. On one hand, he knew striking back could hurt his chance and the chances of others. But there was also the need to "hold your head high and don't let anybody trample over you." And unlike Robinson when he was breaking in with the Dodgers with the pressure of a nation on his shoulders, he wasn't bound by an agreement not to retaliate. So for once, Baylor drew on courage and fought back.

"One guy said the 'N' word to me," Baylor said. "I ran through the gymnasium and tackled him on the auditorium stage. A bunch of kids ended up breaking it up, but that was the last time that guy called me that. And they all knew I was not going to take anything like that."

But that didn't win over the adults. Baylor wanted to play football, but he recalled they gave a uniform to his friend Chambers, then told him they didn't have a uniform for him. But a white student with whom he became lifetime friends, Dean Campbell, son of a local television personality, offered encouragement. Finally, he received a uniform.

"I ended up starting for them, all the time," Baylor said. "They probably hadn't dealt with African-Americans, or blacks or whatever we were called back then. Maybe they'd have them prune their yards. But if you won a football game or a baseball game, that changed a lot of their minds."

By the time he reached Stephen F. Austin High School, integration was growing. And a new challenge landed his way.

"I had to make friends with some of the black students from across town, and they were killing me: 'He thinks he's better than us because he went to O. Henry Junior High School,'" Baylor recalled. "So I was caught in the middle.

"I remember asking one of the guys, 'Do you know who Jackie Robinson was?' And he kind of looked at me like, 'No, who?'"

But Baylor said the athletes came together quickly, especially when they found they were lauded when they played, despite often being shunned in school.

"On Fridays, the cheerleaders would always walk the athletes to class," Baylor said. "I know a couple times the girls got called in by their teachers and told, 'You can't do that to the black guys at all.'"

But Baylor's talent opened opportunities. Darrell Royal, the legendary Longhorns football coach, made him the first African-American to be offered a scholarship by the football program. By 10th grade, Paul Richards, general manager of the Houston Colt 45s, let Baylor know he was a possible first-round MLB Draft pick.

And after a rough go with a coach his first year of high school, Frank Seale took over the baseball program, emphasized fundamentals and let all players know they were accepted. Baylor would make sure Seale was around for World Series appearances or when he was honored as the MVP Award winner.

"He is a lifelong friend, like Dean Campbell," Baylor said. "Our families are close and everything."

When Baylor graduated high school in 1967, the Orioles drafted him in the second round. Yes, it was for athletic achievement, but the day he signed his $7,500 bonus was a sign that Baylor had earned respect. The signing occurred at the State Capitol.

"My grandfather got to see it," Baylor said. "And Congress Avenue, which leads right up to the State Capitol, was named after me for a day when I won the MVP. That was pretty amazing, too."

The tough days stoked competitiveness. Hall of Fame Orioles manager Earl Weaver affectionately called Baylor a "hothead," because he hated losing. He followed the examples of Jackie Robinson and Frank Robinson by playing unapologetically hard, even if a slide rubbed an opponent the wrong way. And his 267 hit-by-pitches -- rarely if ever reacting as if he'd been hit -- make him a toughness legend.

But the real measure of Baylor's toughness came immediately out of high school. He was a center fielder in Rookie ball in Bluefield, W.Va., when future Pirates batsman Richie Zisk of the Salem (Va.) club launched a screaming line drive his way.

"It got in the lights and the ball just kind of hooked on me," Baylor said. "I just kind of threw my [bare] hand out there; it ended up in my hand."

But of even more pride is the fact Baylor has transcended athletic feats.

Baylor and his wife, Becky, have returned to Austin after Baylor left the Angels as hitting coach after the 2015 season. Baylor has fought multiple myeloma (cancer that attacks plasma in the bone marrow) since 2003, but reports he is doing well. And he and Austin have given each other their hearts.

The Clarksville section has changed. Baylor's childhood home was razed to build a highway, and the section now features high-priced homes. However, the church he and earlier generations of his family attended while growing up, Sweet Home Baptist Church, still stands, amazingly. Baylor is heading the committee to restore the church.

"It's 145 years old this year," Baylor said. "I'm busier now in retirement."

Being in Austin also allows Baylor time with his two granddaughters, Brooklyn, 9, and Nola Bee, 5. Hearing Brooklyn's childhood aspirations makes Baylor appreciate his own journey.

"She wants to go to O. Henry," Baylor said. "She wants to go to Austin High School. She's telling everybody.

"It was really surprising that she knew something about that."

Thomas Harding has covered the Rockies since 2000, and for MLB.com since 2002. Follow him on Twitter @harding_at_mlb, listen to podcasts and** like his Facebook page**.