Kerouac's lifelong love of baseball

On March 12, 1969, Jack Kerouac turned 47 years old. Living in St. Petersburg, Fla., at the time, he was known to attend Spring Training games at Al Lang Stadium, not far from the ranch house he shared with his mother and third wife.

If Kerouac had decided to spend that birthday at the ballpark, he would've seen the defending World Series champions, the Detroit Tigers, taking on the woebegone New York Mets, who had just set a new franchise record in 1968 with all of 73 wins.

It was cloudy and unseasonably cool. The temperature topped out at 56 degrees, and there was a cold drizzle. But the author of “On the Road,” the avatar of the Beat Generation, a native of milltown Lowell, Mass., where the winters could be long and brutal, no doubt had a well-traveled flannel shirt to keep him warm at the stadium on Tampa Bay just five miles from his house.

In winter night Massachusetts Street is dismal, the ground's frozen cold, the ruts and pock holes have ice, thin snow slides over the jagged black cracks. The river is frozen to stolidity, waits …

– Maggie Cassidy, 1959

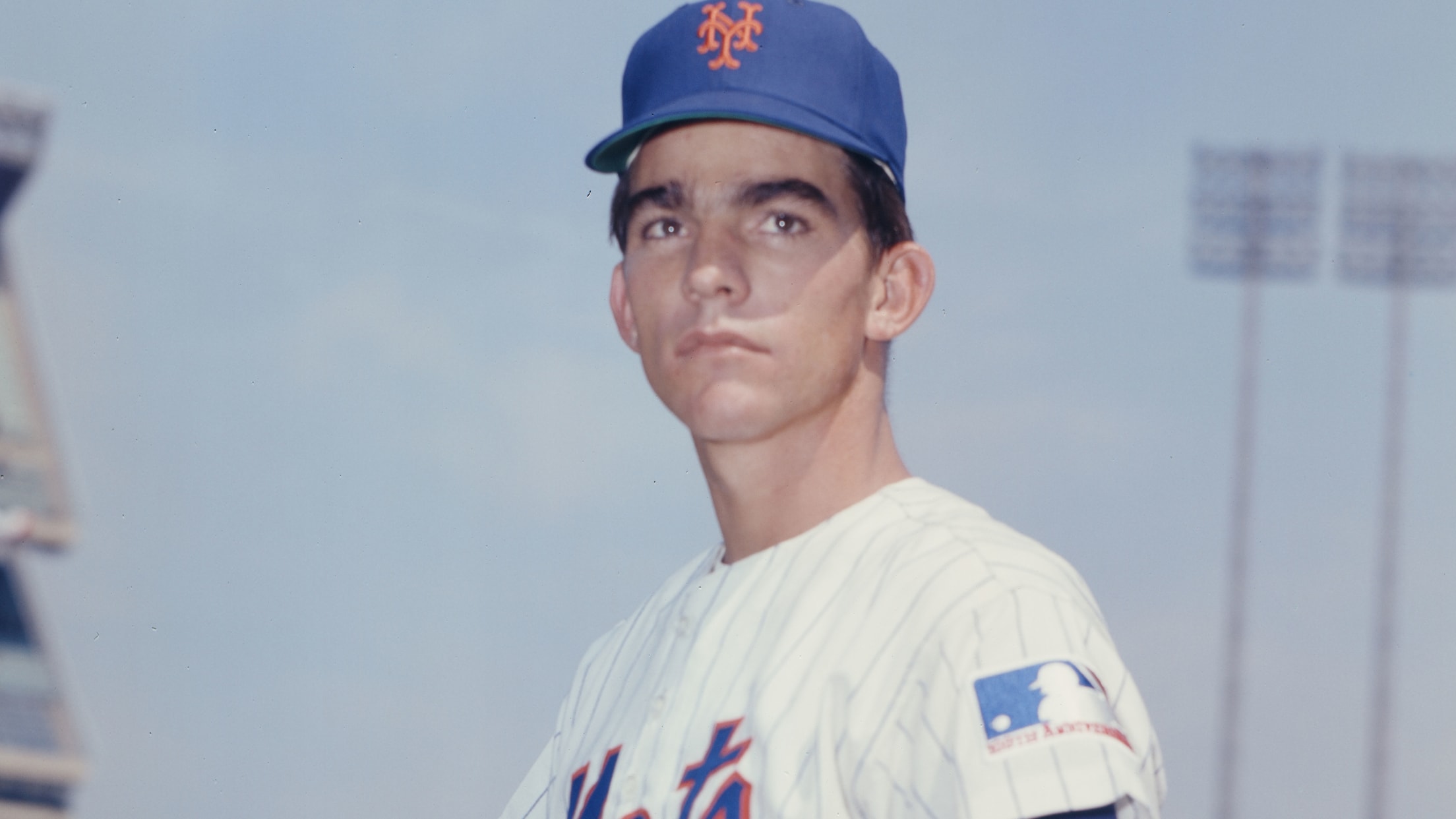

If Kerouac was in attendance that day, maybe the circus music that emanated from the Bayfront Center out past the left-field fence added to the festivities. The Mets throttled the Tigers, 12-0, holding Detroit to just four hits -- none of them coming before there were two outs in the seventh. Gary Gentry, a 22-year-old rookie pitcher who never hit a home run in his seven big league seasons, walloped a grand slam on the first swing of his career, according to Dick Young of the New York Daily News.

It was the last birthday Kerouac would celebrate. Seven months later, on Oct. 21, just five days after those Mets he watched in a Grapefruit League game had won the World Series in amazin’ fashion, Kerouac died of an internal hemorrhage at St. Petersburg’s St. Anthony Hospital. This year would’ve marked his 100th birthday, but he didn’t even make it halfway there.

Growing up in a French-speaking house 30 miles from Fenway Park, the boy known as Ti Jean was drawn to baseball. As early as age 11, he had developed a fantasy game that he would play by himself in the backyard, using a toothpick to hit a marble. Over the years, this game would evolve into a card-based game -- a precursor to Strat-O-Matic -- where one or two players would draw cards, with symbols and scenarios laid out. The outcome of a pitch or at-bat would be determined by the skill of the pitcher vs. that of the batter.

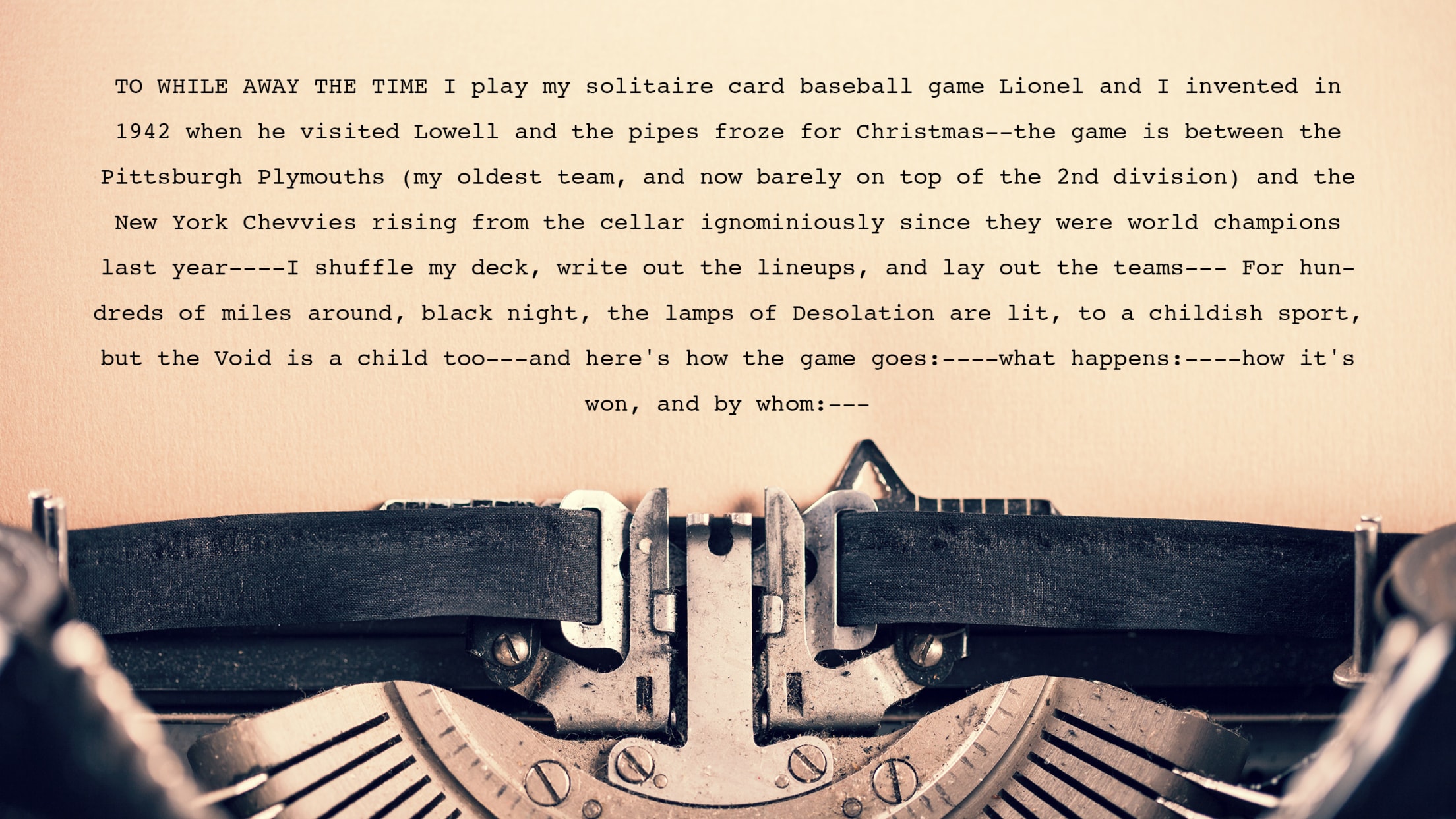

In 1956, while spending 63 days alone as a fire lookout in Washington state’s Cascade Mountains, Kerouac used the game to fight off boredom. He devoted six pages in “Desolation Angels” to recapping one game.

When Kerouac came down from the mountain after two months, one of the first things he did was buy the latest issue of The Sporting News to catch up on the baseball he’d missed, writing, “For after an hour and a half in my room sipping that wine (sitting with stockinged feet on the bed, pillow back), reading about Mickey Mantle and the Three-I League and the Southern Association and the West Texas League and the latest trades and stars and kids upcoming and even reading the Little League news to see the names of the 10-year-old prodigy pitchers ...”

But unlike Strat-O-Matic, Kerouac didn't create cards of famous Major Leaguers. Instead, he conjured every player, often basing them on real-life friends. He made up the teams, too, naming them after colors (Chicago Blues, Boston Grays, New York Greens) or cars (Pittsburgh Plymouths, St. Louis Cadillacs, Washington Chryslers). He would write up descriptions of games, seasons, offseasons, transactions and contract disputes in broadsheet “newspapers” he drew himself, calling them “The Sportsman” or “The Daily Ball” or “Jack Lewis’ Baseball Chatter.”

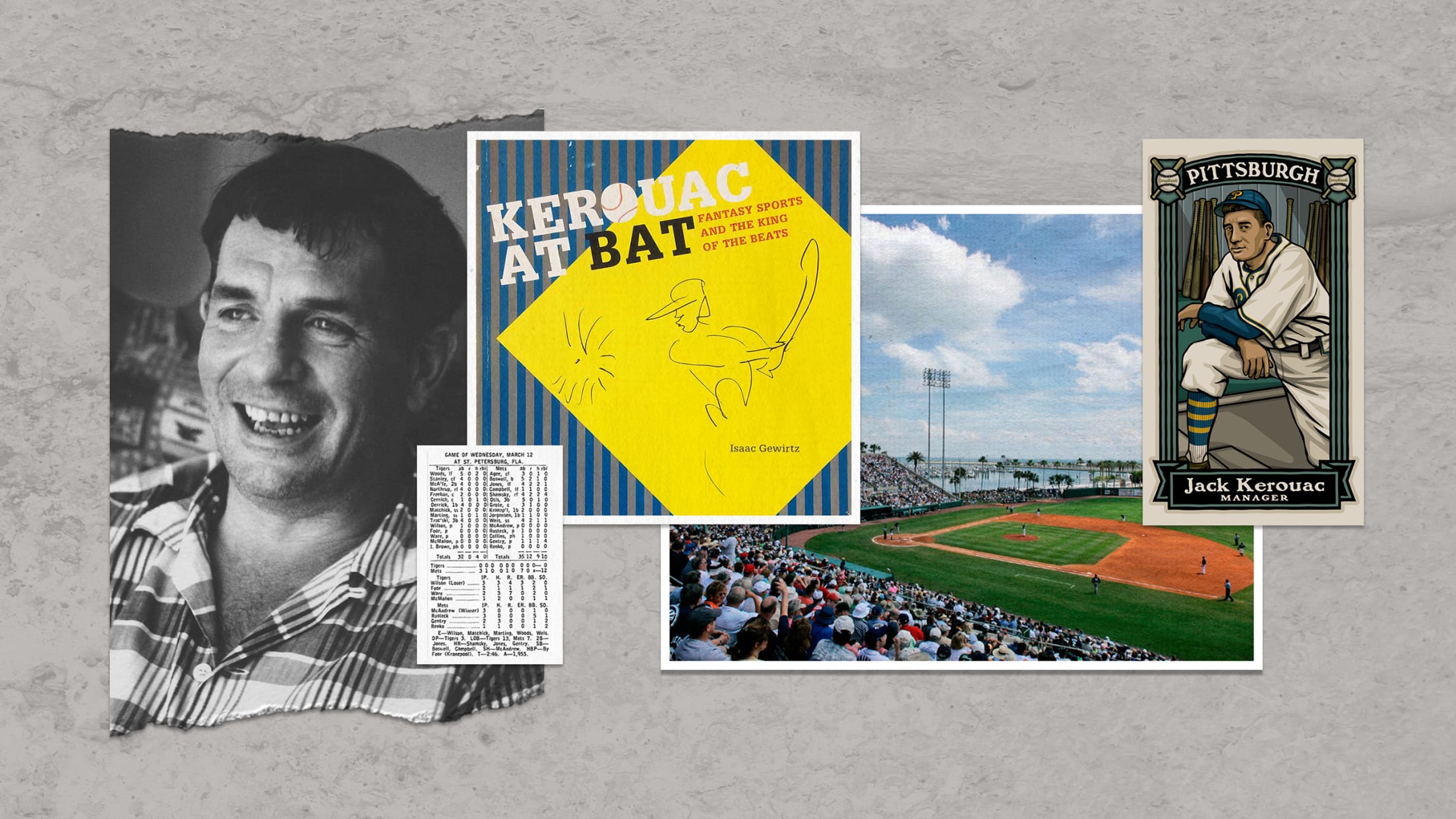

Not surprising for the man who made a name for himself by giving aliases to all his friends and acquaintances in his novels (in part to shield himself from lawsuits), the rosters of Kerouac’s teams were comprised of fictional players with evocative monikers. At first, he pulled the names straight from the Lowell phone book, according to Isaac Gewirtz’s book “Kerouac At Bat: Fantasy Sports and the King of the Beats,” but then he started making them up.

Frank “Pie” Tibbs, Pittsburgh Plymouths: “He wields a long black bat, swinging from the portside, and swings in a wide, upward arc which spells destruction for every pitcher he has met this season so far,” Kerouac wrote in “Jack Lewis’s Baseball Chatter Number One” in 1937. It’s probably no coincidence that Hall of Famer Pie Traynor played for the Pirates from 1920-37, finishing his career when Kerouac was 15 years old.

Buck Barbara, Philadelphia Pontiacs: As described in “Jack Lewis’s Baseball Chatter,” “Buck is a big, stocky, but tall bo[y] and he swings toward his left, or turns on the ball, like a vicious bull; and when he connects, there is a sharp, hard crack, and those third basemen start hopping around. He almost drove Charley Fiskell, Boston’s hot corner man, into a shambled heap in the last game with his sizzling drives through the grass.”

Big Bill Louise, Boston Grays: On Feb. 17, 1961, New York Newsday ran an article by Stan Isaacs, who had visited Kerouac at his home on Long Island to play his fantasy baseball game with him. “I patterned him after Babe Ruth,” Kerouac told his guest. “One day I had him come to bat chewing on a frankfurter.”

Hophead Deane, Washington Chryslers: Deane made the last out in the game Isaacs played with Kerouac. The player got his name because “he wears his hat askew and does silly things,” Kerouac explained. A player named Hophead today would probably be into craft IPAs.

The Sims brothers, Chicago Blues: “Sonny Sims, the center fielder, is like Willy Mays [sic]. His younger brother, Sugar Ray, was just brought up from the minors. He’s called Sugar Ray because he is a flashy character and looks like Sugar Ray Robinson.”

In the spring of 1949, Kerouac headed West on one of the trips that would make up “On the Road.” In Denver one night, he happens upon a softball game. That game was on a field now known as Sonny Lawson Park, the site of the first Negro League game in Denver.

Later, in between travels, Kerouac was back on the East Coast at his mother’s house with Neal Cassady, tracking three ballgames at once.

In September 1951, as he fretted over the 120,000-word scroll he had written chronicling these adventures, Kerouac's journal reveals that he watched the Giants-Dodgers playoff series that ended with Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World.” The Giants trailed, 4-1, entering the ninth inning; their starter, Sal Maglie, having given up four runs in eight innings before hitting the showers in the clubhouse out beneath the center-field bleachers. With Brooklyn three outs from a win, Kerouac imagines not Russ Hodges excitedly exclaiming a Giants win, but Red Barber announcing the opposite -- “The Dodgers win the pennant!”

That moment stuck with Kerouac, more than the Yankees’ victory over the Giants in the World Series. Over the next week, the Fall Classic got but a single mention: “MONDAY OCTOBER 8, 1951 – Did scripts – thought of going to sea -- fiddled -- faddled – Yanks beating Giants -- it started off as a beat day but ended up with a great discovery of my life. …”

Kerouac continued to follow the game the rest of his life. One day in 1965, he showed up at the newspaper offices of the Evening Independent, the afternoon edition of the St. Petersburg Times. “Jack Kerouac dropped by the office last night and batted out three stories while I was trying to get one paragraph right,” the sports editor, Mike Fowler, wrote in the paper the next day.

“In Mid-June My Ideas About The Major League Race,” the headline read. “This old sorry horse will now predict the end of the pennant race, and lay it on the line on a 5 cent bet with the thousands of eager fans who will challenge me no bout contest.”

His predictions? The Tigers in the American League, the Braves in the National, led by “the greatest living ballplayer Hank Aaron” and “the Hall of Fame Eddie Mathews (right among us now).”

“The Milwaukee Braves, if the pitching holds up, have the power to DOWN anybody in the National League. Franchises have nothing to do with this. Simple baseball is beautifully played before people. As Dizzy (Jerome Hanna) Dean says, ‘Aint nothin I like better than a good ball game.’ Every American is interlocked with Cooperstown. (Look out for the Dodgers in the National, and the Yanks in the American.)” -- The Evening Independent, July 16, 1965

He was right to throw in the Dodgers at the end there -- they beat the Twins in seven games to win the 1965 World Series.

Baseball may have been one of the few things that made Kerouac happy in his final years. Now in his 40s, alcoholism taking its toll, he often sat at home, shades drawn, a bottle or a beer at his side as he watched TV. He still wrote, though; in addition to his ubiquitous pocket notebooks and journaling, he composed “Vanity of Duluoz” -- Jack Duluoz being his alter ego -- in 1967. It looks back on his teenage years and young adulthood (roughly ages 13 to 24), with baseball, as ever, evoking pleasant memories.

We also played a lot of baseball in Dracut Tigers field, scrub it’s called, where you get to bat and get ten whacks out, if you keep hitting singles or homeruns you keep going till you’re out ten times, either from fly ball or thrown out at first, though none of us bothered to run them out. Then you go into right field and work your way back.

– Vanity of Duluoz, 1968

Thanks to James Hartzell, president of the Friends of Jack Kerouac in St. Petersburg, and Margaret Murray, a board member for the organization who developed a bike tour of Kerouac sites around the city that includes Al Lang Stadium. Click here to read more about Gary Cieradkowski’s card depicting Jack Kerouac as the manager of the Pittsburgh Plymouths, and here to read about Kerouac's time in St. Petersburg.