Were these the worst -- or best -- jerseys ever?

Saturday marked the 25-year anniversary of one of the most notorious promotions in Major League history, the cult classic known as "Turn Ahead the Clock Night," which included the brief but memorable reign of the Mercury Mets. A version of this story originally ran in July 2019.

At some point,

The year, purportedly, was 2021. The Mets, purportedly, had long since moved to the closest planet to the sun, and they were returning to earth for a single game at Shea Stadium. They brought with them their equipment, their extraterrestrial features and their fashion sense, all of which would become the fabric of one of the most memorable promotions in Major League Baseball history.

Preparing for his final start before the event, Hershiser did not yet understand what sort of merriment, venom or nostalgia the Mercury Mets might evoke; he just thought the jerseys were ugly. That was a problem. As the July 27, 1999, promotion approached, Hershiser found himself sitting on 199 career wins. Knowing the media would be paying close attention until he reached 200, he was queasy about what he perceived as a sartorial issue.

“The motivation going into the last start,” Hershiser said, laughing, “was that I didn’t want to have to go for it in that uniform.”

A different kind of throwback

The seeds of MLB’s rocket through time were planted not on Mercury, nor in Queens, but at the old Seattle Kingdome. Lacking a lengthy franchise history, and thus a catalogue of throwback uniforms from which to choose, the Mariners would periodically dress up in the garb of other former local professional teams -- the Seattle Pilots or the Pacific Coast League’s Rainiers or the Steelheads of the Negro Leagues.

It was during one of these throwback events in 1997 that members of Seattle’s marketing and management teams began to brainstorm promotions for the following summer. Someone tossed out the idea: “What if we went into the future?”

Gentlemen, we're going into the future.

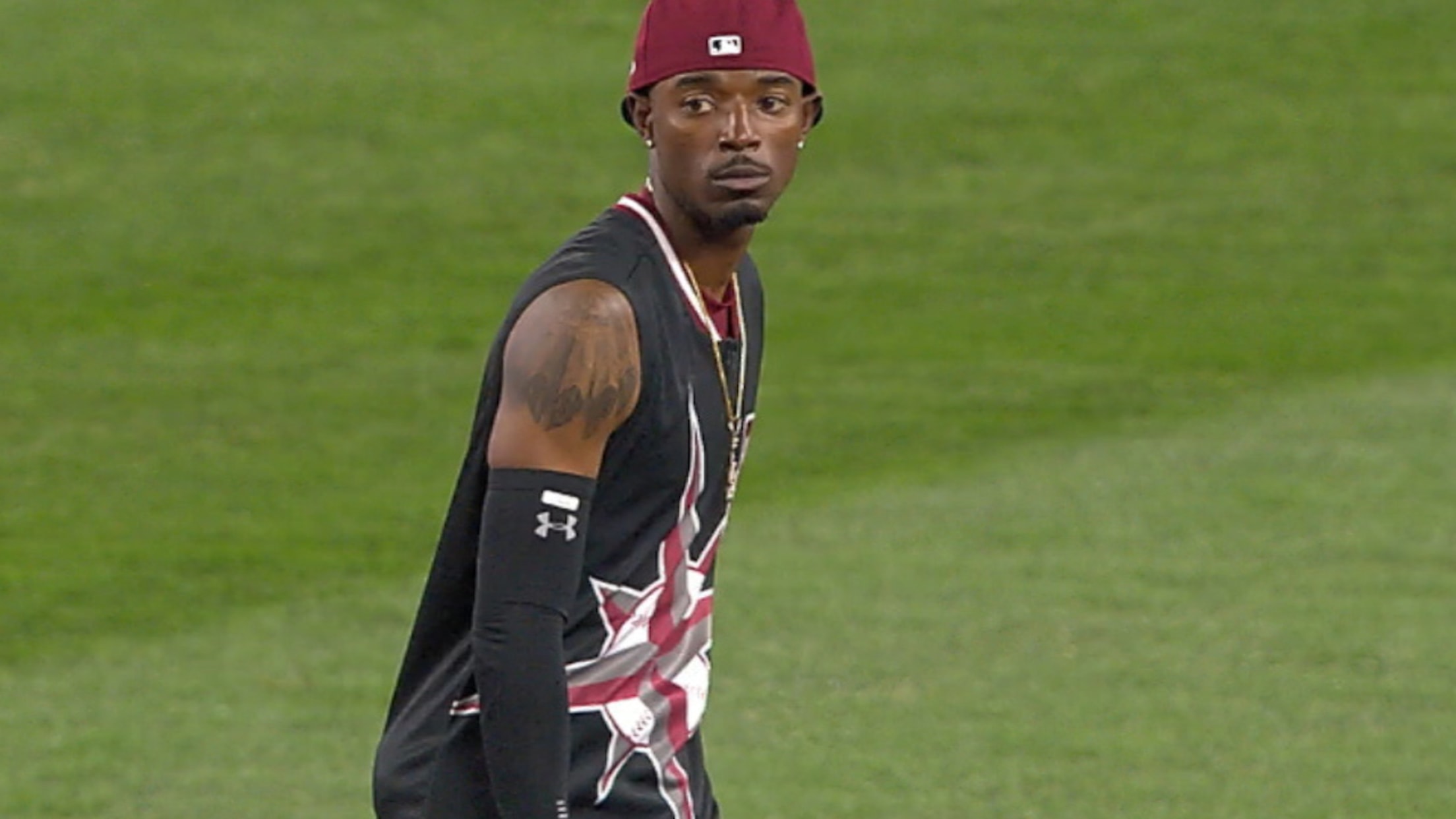

Ken Griffey Jr.

“Everybody kind of looked at each other,” recalled Kevin Martinez, a Mariners marketer for the past 26 seasons. “‘What would that look like? What would that be?’”

A day or two later, Martinez brought the idea to Seattle’s superstar,

Rather than mimic some element of the past, the Mariners tried to predict the future. They weren’t timid. On the night of the game, which was played on July 18, 1998, against the Royals, Seattle invited actor James Doohan -- Scotty from “Star Trek” -- to throw out the ceremonial first pitch, driving him to the mound in a DeLorean and sending a robot out to deliver the baseball. The out-of-town scoreboard depicted expansion teams like the Saturn Rings, the Mercury Fire and the Pluto Mighty Pups, among other, more terrestrial MLB clubs. Before the game, Griffey bounced around the clubhouse wielding a can of spray paint, coloring the shoes of each of his teammates to match his own custom-made silver Nike kicks.

“Gentlemen,” Griffey told his teammates as he moved around the room, “we’re going into the future.”

Griffey also encouraged the Mariners to go for a casual look with their jerseys untucked, reasoning that umpires would allow it because the 1976 White Sox had done the same. He wasn’t wrong. So it came to be that with his hat backwards and his jersey tail flapping, his biceps exposed and a pair of silver spikes on his feet, Griffey ran into the left-center-field fence to rob Larry Sutton of a hit -- “a classic Ken Griffey Jr. catch,” as Martinez called it.

Not long after, the Kingdome’s press-box phone rang.

“What in the world is going on out there?” came the voice on the other end of the line.

It was an ESPN producer calling from Bristol, Conn., with the power to make the Mariners’ event go as viral as things could back in 1998. That night, the network opened “SportsCenter” with a segment highlighting Seattle’s “Turn Ahead the Clock” night. A group of MLB marketers in New York took notice. They scheduled a business trip to Seattle, where Martinez handed over his uniform designs, photographs and scripts from the event.

The idea was to take the theme nationwide.

Back to the future

“You remember the old cartoon, ‘The Jetsons’?” Steve Savino is saying from his office at Lehigh University. “We’re fast-forwarding to that kind of timeframe where everything is automated, and people are in flying cars or whatever. So how would they dress? What would they look like?”

Savino is a professor now, teaching undergraduate students and MBA candidates at Lehigh. In 1999, he was the executive vice president of global marketing for Century 21, a real estate agency looking to rejuvenate its brand. Century 21 had recently purchased rights to the Home Run Derby, at a time when

“We are Century 21,” Savino said. “And we are heading into the 21st century, are we not?”

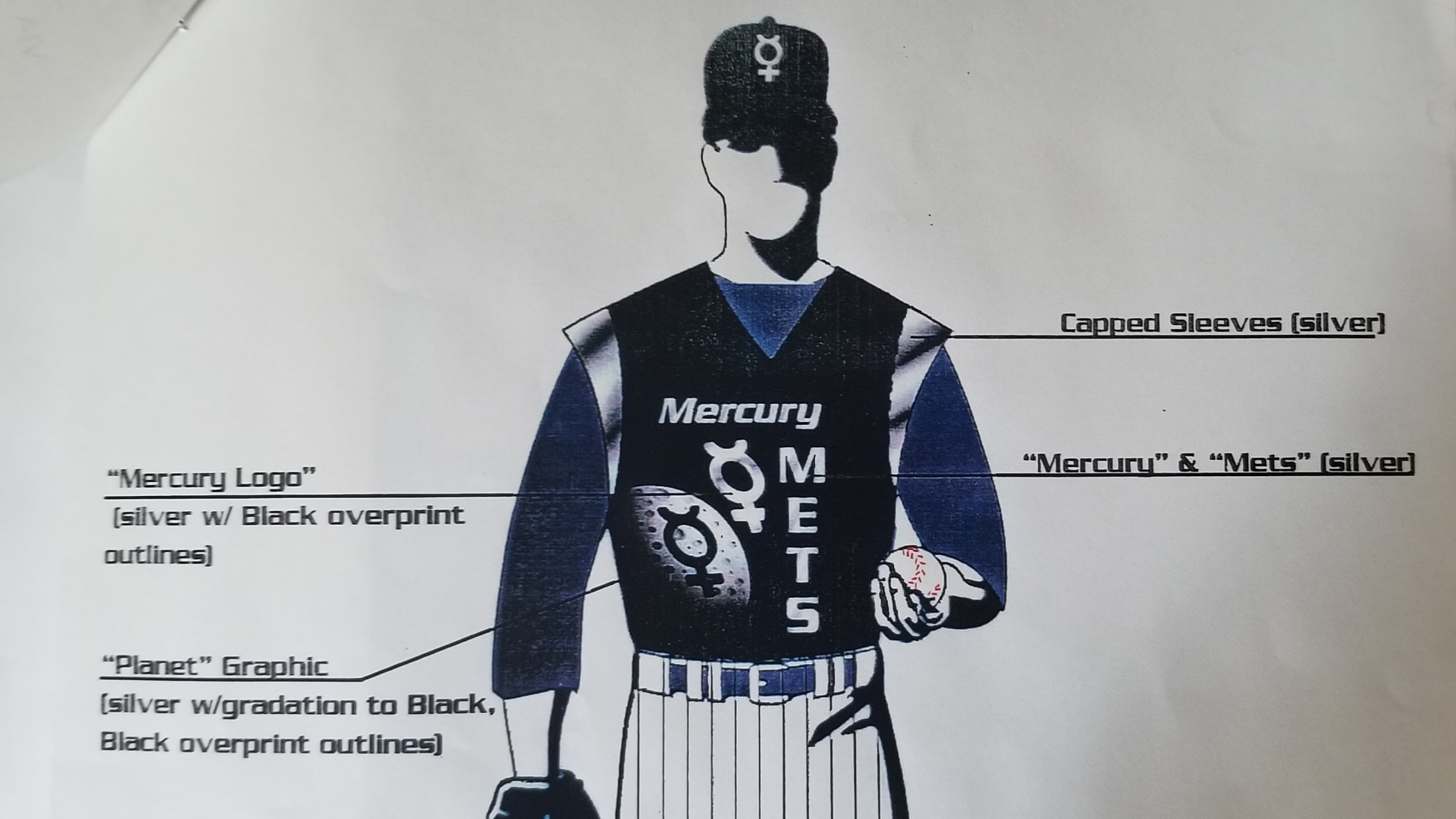

With the Mariners providing the blueprint and the real estate firm offering financial backing, MLB was on its way to taking its “Turn Ahead the Clock” coast to coast; it simply had to streamline things. Rather than mock up 30 uniform designs, the league created one boilerplate that every team could use -- a sleeveless, V-neck jersey with cap sleeves and an oversized team logo on the front.

We are Century 21. And we are heading into the 21st century, are we not?

Steve Savino

The grand reveal took place at MLB’s offices in Manhattan, where the league announced details of the promotion to a group of sports and business writers. For the press conference, decorators transformed the space into a future wonderland, complete with jersey mockups and a plasma globe that pulsed with energy when people touched it. From an adjoining break room spilled a cooler of dry ice, which created enough smoke for one member of MLB’s clerical staff, despite assurances that all was well, to pull the fire alarm.

“So in the middle of this press conference where we had everyone, the fire department shows up in their full regalia,” said Anne Occi, MLB’s vice president of design. “It was like a sitcom. You couldn’t make it up.”

The future had arrived. In the next day’s New York Times, among other publications, details of the promotion went public. Twenty-two of MLB’s 30 teams had signed on to turn ahead the clock, with eight clubs -- the Yankees, Dodgers and Cubs, most prominently -- declining to change their uniforms even for a day. Most of those on board featured oversized versions of their normal logos: The Rockies’ jersey tops, for example depicted a giant, snow-capped massif, while the Pirates -- the Mercury Mets’ opponent on that fateful night -- had a buccaneer head spanning more than a foot in length.

The Mets proved most ambitious. Although their initial jersey mockups also featured a supersized, interlocking "NY" on a plain black background, their marketing team decided that wasn’t memorable enough. Team officials asked MLB if they could design their own uniforms for the event, going as far as to ask permission to change their name and logo for a day.

“Basically as a group, we decided, 'Let’s go big or go home,'” said Kit Geis, the Mets’ director of marketing at the time. “Let’s do this in a way that will cut through the clutter, and be committed to it.

“It’s like in comedy, you’re committed to your bit? We were going to commit to the bit.”

Spring forward ... sort of

Hershiser came to the Mets after his 40th birthday, with 190 wins already to his credit. While the 1988 NL Cy Young Award winner struggled over the first three months of the '99 season, a strong offense helped him win eight games. Hershiser’s ninth victory came on July 6, putting him on the brink of 200, but he lost two straight as the Mets revealed plans for their galactic extravaganza. Hershiser looked at the calendar and realized he needed to win again on July 22, lest he go for No. 200 as a Mercury Met.

The team’s plans for “Turn Ahead the Clock” night, Hershiser knew, were ambitious. Not only had Geis and her department redesigned uniforms, but they had also created a basic plot: The Mets, at some point, had moved to Mercury, some fraction of a lightyear away from Earth. As part of an interplanetary promotion, they were returning to Queens for a 2021 game at Shea Stadium. In the time between, baseball had changed. Left field was now “left quadrant.” Innings were “sectors.” Concession stands were “replenishing depots.”

Oh, and the players were aliens.

On the Shea Stadium video board, images flashed of each extraterrestrial as he came to the plate. Rickey Henderson stepped out of the batter’s box to examine his likeness before his first at-bat: green with pointy ears and an extra eye. Robin Ventura was bald with a tuft of green hair. Manager Bobby Valentine had horns growing out of his skull. Mets players known for their fielding prowess were given tentacles for arms.

“I didn’t want to look at it,” said Hershiser, who managed to get that 200th win on July 22 after all, a 7-4 victory against Montreal.

The Mets’ event was exactly what Century 21’s marketing team wanted -- a true buy-in to the “Turn Ahead the Clock” campaign. But it proved imperfect, both in Flushing and elsewhere. In many cities, due to late planning, uniforms showed up to the ballpark mere hours before first pitch. (They never arrived in Boston because a hurricane hit the production facility in North Carolina.)

They’re not actually going to go out on the field looking like that, right?

Howie Rose

Unlike at the Kingdome, where Griffey’s enthusiasm fueled the project, not every player knew about the event in advance -- or was on board with it. Some disliked the change in jersey material, which was shinier and smoother than the normal polyester blend. Others considered the idea childish. Even at Century 21, Savino feared players reacting like Mets pitcher Turk Wendell, who called the uniforms “super ugly … super ugly.”

“The first time I saw them,” recalled Mets broadcaster Howie Rose, “I said, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa. They’re just taking pictures of them, right? They’re not actually going to go out on the field looking like that, right?’”

Of course, the Mets did, with Hershiser pitching and a star-studded lineup -- Henderson, Ventura, Mike Piazza and others -- behind him, several of whom praised the Mercury Mets’ look. Those watching at home learned of the promotion during a television introduction, in which first baseman Matt Franco gushed about both the uniforms and the benefits of playing on Mercury -- “no gravity there, so you hit bombs … moon shots.” Fans in the ballpark could see well enough what was happening, despite some confusion over what the mercury symbol meant. All in all, things seemed to go fine.

“We were prepared, to be honest with you,” said Pirates outfielder Brant Brown. “We were like, ‘OK, it’s ugly. Now let’s try to win a baseball game.’”

Tabloid blowback

The morning after New York’s 5-1 loss, the Daily News’ back page headline blared a single word in oversized print: “UGLY.”

“Mets look bad, play even worse in loss to Bucs,” read the subhead, much to the chagrin of the team’s marketing department. Newsday ran the headline, “Lost in Space.” Hershiser was quoted in both papers comparing the event to a circus. The Village Voice, which housed Paul Lukas’ nascent “Uni Watch” column, posited that “maybe a Y2K meltdown wouldn’t be such a bad thing.”

In Flushing, at least, “Turn ahead the Clock” didn’t get as warm of a response as hoped. Elsewhere?

I think out here in Seattle, it’s a night that people remember and had fun, and you had the biggest player in the game at the center of it.

Kevin Martinez

“It’s got a couple of different personalities,” said Martinez, the Mariners’ marketer. “I think out here in Seattle, it’s a night that people remember and had fun, and you had the biggest player in the game at the center of it. Certainly when it went national and the media that followed it, it was so foreign to so many people, and over-the-top. I don’t know if it had necessarily the same reaction.”

Initially, MLB wanted to continue the promotion into the year 2000, but the mixed media reaction caused Century 21 to withdraw its backing. While the Mariners’ event proved popular enough that the team reprised it in '18, the Mets have no such plans, preferring to keep the Mercury Mets at (robotic) arm’s length.

Still, two decades have a way of softening edges. Mercury Mets jerseys draw plenty of interest when they turn up on eBay and other online sites. Images of the uniforms and scoreboard graphics often find their way onto social media. Savino, who has long since moved on from Century 21, kept a collection of jerseys from the event. Even Rose, a uniform traditionalist who does not look back on the event “fondly or nostalgically,” has his Mercury Mets jersey stowed away at home.

“The same thing that maybe caused criticism at the time is what makes that hat so collectible today,” Geis said. “At the time, the press just likes to talk, and they were like, ‘Maybe the Mets took it too far.’”

Steve McKelvey, whose PSP Sports marketing firm worked with Century 21 on the deal, disagrees with that assessment. McKelvey, who is now a marketing professor at UMass-Amherst, says the Mets were the only team to capture the full spirit of the promotion that summer, with their interplanetary move, their scoreboard graphics and other paraphernalia. The whole point, McKelvey said, was to be a little silly, to draw some attention by being a little weird.

“In hindsight,” Geis said, “everything is fun again, right?”