Back in December, the Reds made one of the more interesting moves of the offseason, signing Mike Moustakas to a four-year deal worth $64 million. Moustakas is an above-average offensive player (114 OPS+ over the last five seasons), and the Reds scored the sixth-fewest runs in baseball in 2019, so you get that part. They want to win. Thus, they added Moustakas, Nick Castellanos and Shogo Akiyama to their lineup, and Wade Miley to their rotation, while the rest of the National League Central has stood pat or stepped backward. Sensible enough.

Normally, that might be the end of it -- except Moustakas is a third baseman, and he's not coming to play third base. That's because the Reds have star third baseman Eugenio Suárez signed through 2024, and across the diamond, they have Joey Votto signed through 2023. So, Moustakas isn't headed to Ohio to play third, or first, or a corner, at all. He's coming to play second base, without even having the designated hitter available should this not work out. Basically, it's either going to go well, or it's going to go extremely not well.

(While he might start the season at third, given Suárez's shoulder injury, Moustakas should still play most of his season, and those to come, at second.)

For a 31-year-old not known for his speed and with a serious knee injury (2016) on his resume, this isn't exactly the usual career path. Will this work? Can this work? Maybe we can try to find out.

Milwaukee tried this in 2019, briefly

We thought maybe we would have answered this question in 2019. Remember, the Brewers tried this first; Moustakas was named Milwaukee's second baseman in Spring Training, and he played 21 games there in March/April. But it didn't last, as he played just 26 games at second base over the remainder of the year, compared to the 105 total games he ended up playing back at third base. After a full game at second base on June 27, he made just a single additional start at second over the final three months of the season, and even in that game, he was still playing third by the eighth inning.

Now, that's not entirely based on his own performance. It's as much or more because on June 28, incumbent third baseman Travis Shaw (hitting 164/.278/.290 at the time) was optioned to the Minors, while prospect Keston Hiura was recalled to take over second base. The resulting shuffle left Moustakas back at third base. He remained there for the rest of the season.

But still, it leaves us without a great deal of sample size to look at. Over his career, Moustakas has played 8,833 2/3 defensive innings, and only 359 2/3 of them (or about 4%) have come at second base. It's just not something he's done that often.

Then again, "playing second base" is a complicated construct these days. Moustakas had never played the position professionally before 2019, right? Yet here he is in the 2018 postseason, making a strong diving play on the right side of the infield to rob Cody Bellinger in Game 5 of the NL Championship Series, while "not playing second base." That sure looks like playing second base to us.

That play came while Moustakas was listed as a third baseman, yet shifted over to the right side against the lefty Bellinger. Thanks to the shift, that happened kind of a lot last year, as Milwaukee shifted on 55% of plate appearances by opposing left-handed hitters, the seventh-most in baseball. (The Reds, it's worth noting, were next, at 49.4%.)

So this isn't entirely about "what does he look like while playing second base," and more about what does it look like when he's at second base." For years, that was a difficult thing to parse, but the new Statcast defense metric Outs Above Average lets you do exactly that. When we take a look at Moustakas, we find something interesting. If we set aside "what position he was playing" entirely and just look at "where on the field was he playing," check out how his Outs Above Average came out.

3B: -3

2B: +2

SS: +1

In 2019, he was a mild negative at third base. He was a mild positive at second base. (And yes, the shift put him where shortstops stand as well; check out this nice play to take a hit away from A.J. Pollock.) Maybe the Reds are on to something here.

What does it mean to play second base in 2020?

Wait, let's pause here for a second. What is second base these days? Because it's not the same thing as it once was. For years, second base was the domain of the defensively gifted middle infielders who didn't quite have the arm for shortstop. They'd hit second, they'd move the runner over, they'd make contact, they'd turn double plays.

But that's not necessarily true anymore. In 2016, for example, second basemen outhit all three outfield positions for the first time ever. While that hasn't remained consistent in the years since, it was still a notable achievement. That year, a new slide rule meant to protect infielders went into effect, lessening the concern of an inexperienced infielder being taken out on a slide at second, following the Chase Utley/Rubén Tejada incident.

"The focus on offense combined with the slide rule has definitely lessened the defensive importance of second basemen," longtime Major League catcher and manager Brad Ausmus told ESPN's Buster Olney earlier this month. "The art and nuance to turning a double play has basically disappeared. It's much easier to put an inexperienced position player -- who probably adds offense to the lineup -- and teach him to turn two."

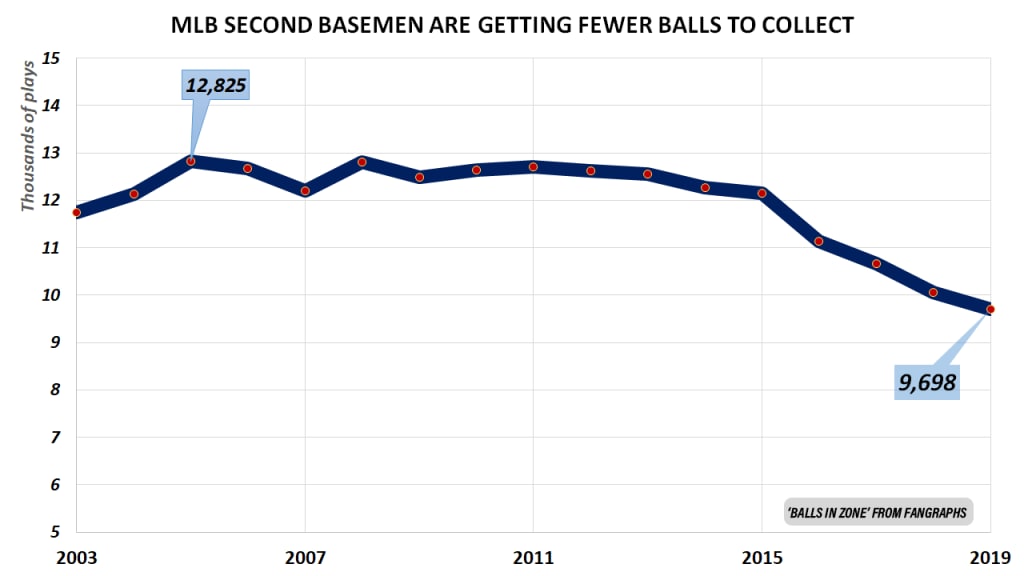

That has played out on the field. In 2000, for example, second basemen had a hand in 3,322 double plays. In 2019, that had fallen to just 2,744. But that's merely an entryway to the issue you already know about: With strikeouts massively up, home runs breaking records and everyone trying their best to avoid ground balls, second basemen simply aren't getting the same number of opportunities to worry about.

That's a 25% drop since a high in 2008. In terms of simple "putouts," that's dropped from 9,984 in 2000 to 8,026 in 2019, a drop of nearly 20%. We just saw about 11,000 more strikeouts than we did in 2000, and 1,100 more home runs. Those not-in-play balls have to come from somewhere, and this is where.

After all, Moustakas isn't the first to do this. Shaw did it reasonably well in 2018, and the Dodgers have given Max Muncy, another slugger who doesn't fit the traditional profile, 83 games at second base over the last two seasons. He's been capable enough. Between fewer balls in play, fewer takeout slides and better positioning, the requirements of second base just aren't what they used to be. Maybe this can work.

What did he look like playing second in 2019?

In 2019, Moustakas had 91 batted-ball opportunities that were assigned to him while he was playing in the second base area. Most, but not all, came while he was "playing second base," because as we pointed out, there are still shifts over from third to account for. (In 2018, he had no shifted-over plays in the regular season and just two in the postseason, and in 2017, on the generally anti-shift Royals, he had none at all.)

(Note that this number will differ from what you see on other sites, as we're looking just at tracked primary fielding opportunities, not plays where he's receiving a throw or competing a relay. Learn more about how this works here.)

On those 91 opportunities, based on the difficulty of each one, an average fielder would have been expected to convert 88% of them into outs. Moustakas actually converted 90% of them into outs. If that +2% value added doesn't seem like a huge gap, nor is it the huge negative you might have otherwise expected. Eighty-three players had at least 50 opportunities in the second base spot last year -- this includes shortstops like Marcus Semien and Elvis Andrus -- and the range goes from +8% over expected at the top to -5% under expected at the bottom. Moustakas was tied for 13th. It's not great, but it's playable. And isn't that what we're looking for here?

So let's break down those 91 plays:

1. Most of them were considered to be easy, and he made them

Of the 91 plays, 79 (or about 87%) had an estimated out probability of 90% or higher. That is, when other fielders have received a play with a similar set of inputs (distance to ball, time to ball, distance to base, runner speed, etc.) they're generally made nine times out of 10. These are the plays that any competent infielder simply needs to make.

"Defensively, they put you in spots where the ball is going to be hit," former Red Sox manager Alex Cora told the Boston Globe last year. “It’s not like a tough play. They put you in a spot where most likely the ball is coming right at you, so it’s a routine play.”

To Moustakas's credit, he did make those plays. We just called 79 plays "easy" ones, and he made 78 of them. While we often think about highlight plays when evaluating infield defense, a huge part of it is simply just taking this kind of routine grounder and not screwing it up.

Or this:

Those plays don't look like much, because they aren't, but they need to get made. Moustakas did in nearly every case.

2. Four of them were nearly impossible.

Not every play is one that a fielder should make, and four of the 91 had an expected out probability of 10% or less. Like this one, for example. You can imagine how a top fielder could have made a spectacular catch on this ball, but it also doesn't hurt Moustakas very much that he didn't get to it.

3. He made half of the midrange chances.

The remaining eight were a little more competitive, between 30% to 80% likely. These are really where fielders can separate themselves from the crowd, and eight of these plays aren't really enough to judge anyone on. Still, he made four of them, including a long popup run and a few requiring relatively deep throws from a shifted right field.

Here's one of them that he was unable to complete -- and this is the kind of play, running away from first base and throwing across his body, that a third baseman doesn't have to do all that often:

So can Moustakas play second base? Over a full season, we don't know. Over several seasons, we definitely don't know. This has the secondary effect of preventing Nick Senzel from returning to the infield, but keeping him in a relatively over-stuffed outfield. This still definitely might not work.

But the signs are there that it could. After a lifetime on the left side, Moustakas should have no problem with the throws, or the easy grounders, and second basemen just aren't asked to do the same job they once were. He doesn't need to be great, and he won't; he just needs to be competent, and there's reason to believe he can be. (Again: Muncy.) Ultimately, it comes down to this: Reds second basemen were dreadful last year, hitting a mere .221/.288/.390, one of the weaker marks in baseball. They were good but not great in the second base area, at +2 OAA. It's difficult to believe that Moustakas can't improve upon all that.