Yanks' 2001 WS run comforted grieving NYC

The boy draped his slight frame over a wall near first base at what was then called Bank One Ballpark, clutching a pinstriped piece of poster board with large blue letters reading: "YANKEE FAN TODAY TOMORROW FOREVER." Warming up for Game 6 of an emotional World Series like no other before it, Derek Jeter eyed the sign and flipped a baseball to the 11-year-old.

"The 2001 World Series," Gerrit Cole said two decades later, "was probably the only time the entire nation was rooting for the Yankees."

Indeed, a country wounded by the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon found solace within the rhythms of professional sports, with baseball playing a healing role. Rained out the previous night, the Yankees had been scheduled to host a doubleheader against the White Sox at Yankee Stadium. Both games were postponed after the roars of two hijacked airliners pierced the crisp autumnal blue sky over Lower Manhattan.

Like the rest of the world, the Yankees fumbled for remote controls to make sense of their new reality. At NYU Hospital, Jorge Posada glimpsed images of the flaming towers on broadcast television as he rewound a VHS tape for his son Jorge Jr., who was awaiting a challenging surgical procedure on his skull. Posada witnessed nurses scramble to prepare beds for victims who never arrived.

With telephone lines flooded, the catcher somehow broke through and left a message on Jeter's cell phone, instructing his teammate and friend: "Let me know if the game is canceled tonight. Something happened at the World Trade Center." Jeter awoke in his Manhattan apartment to discover that New York's skyline, and the world, had been forever altered.

"I turned on the TV, and I saw what everyone else saw," Jeter said. "It was on every channel, so it didn't really make a difference what channel you had on."

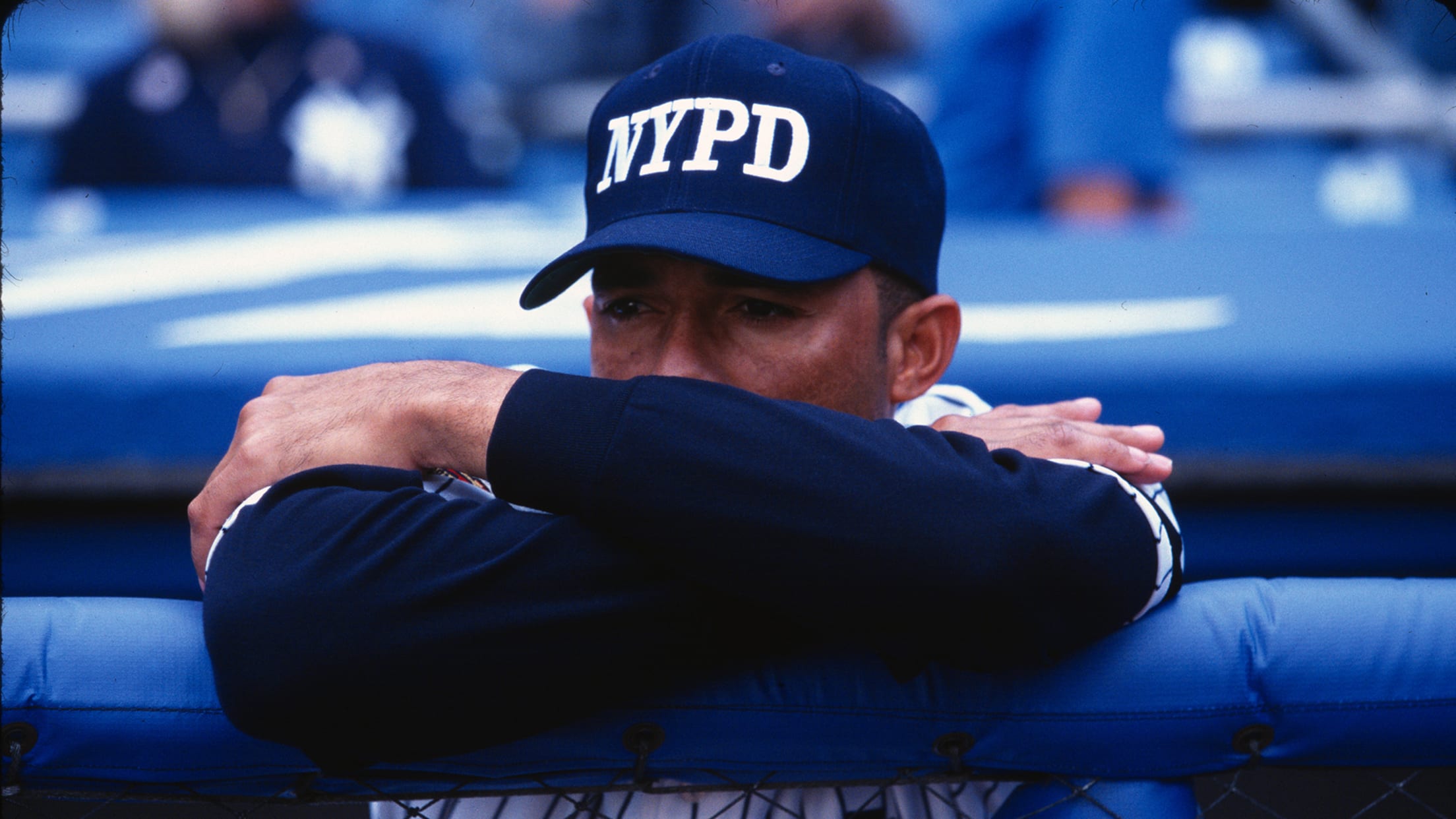

Baseball paused for a week, and with no games to play, both the Yankees and Mets shifted into roles as consoling ambassadors of New York City. Many Yankees loaded into vans to visit emergency workers staging at the Jacob Javits Convention Center, comforting family members waiting for news about loved ones at the 69th Regiment Armory. Joe Torre, the Yankees' manager at the time, recalled wondering if his team belonged in that environment.

"That's when the emotion really hit you," Torre said. "We're just a baseball team, and these people are experiencing the game of life. One family waved us over, and [outfielder] Bernie Williams went up to the woman and said, 'I don't know what to say, but you look like you need a hug.' There was something for us to do, and that was to try and distract them. I never realized how important baseball was until 9/11."

In the aftermath of the attacks, Williams recalled questioning how athletes who run, hit and throw would be of any use in the mourning metropolis.

"That kind of line of work seemed a little insignificant in light of what was happening," Williams said. "Everything started turning around when we started visiting the Javits Center, [St. Vincent's] Hospital and the armory. When they started saying, 'The Yankees are here! The Yankees are here!' It gave people a smile in that moment."

Players visited firehouses, sharing stories with members of an FDNY which lost 343 souls on that terrible day. Paul O'Neill was stunned by the mangled steel and hissing smoke at Ground Zero, which he said "looked like a movie set." City streets were papered with missing persons flyers. Games resumed on Sept. 17, but the Yankees didn't take the field until the following night, facing the White Sox in Chicago. During pregame ceremonies, fans unfurled a large red, white and blue banner at Comiskey Park: "Chicago New York: God Bless America." A standing ovation greeted the Yankees as they set foot upon the grass.

"Back then, it was almost an uncomfortable feeling for all of us when we first got back to playing baseball," Jeter said. "The first thing you think about is, 'Does this really matter? We're playing a sport.' The thing that we figured out was, even if it was for a short period of time, three hours a day, we gave people something to cheer for. We felt as though we were playing for more than just ourselves. We felt as though we were playing for all of New York."

The Yankees charged through the remaining 18 games of their regular-season schedule, clinching their fourth consecutive American League East title. The dynasty was in full bloom, having secured four of the last five World Series titles. Within city limits, there had been no greater event than the 2000 "Subway Series," when the Bombers bested the Mets in five games. Yet, that New York-New York showcase had been a turnoff to the rest of the country, at least according to TV ratings.

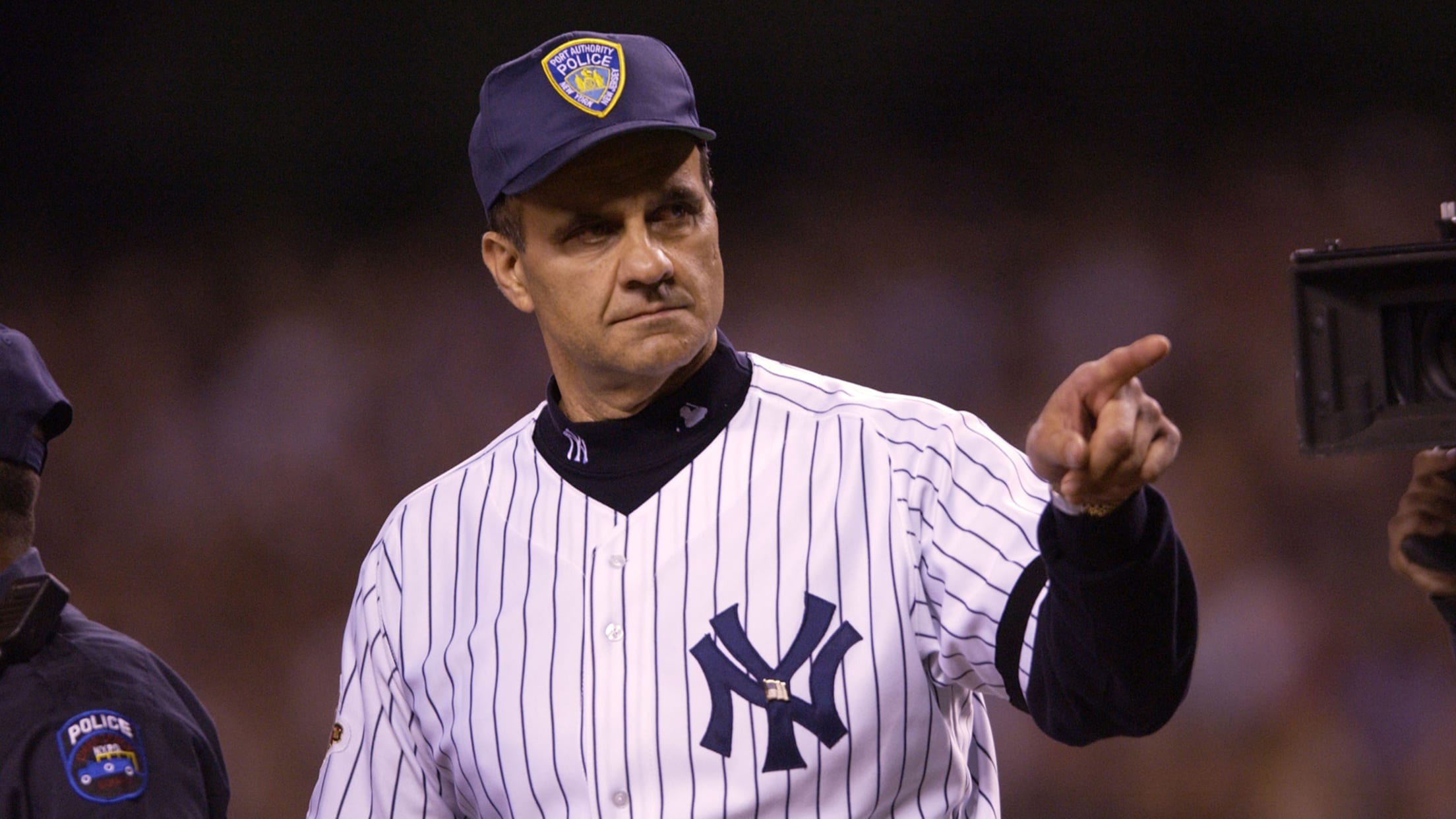

As the Yankees sought the 27th championship in franchise history, their cheering section had swelled. Caps with their interlocking "NY" logo seemed as plentiful as the stars-and-stripes flags whipping from Accords and Camrys on America's highways, many bearing "NEVER FORGET" bumper stickers. Torre told his players that their caps no longer represented a baseball team, but an entire city.

"I never saw so many people rally around the national pastime," O'Neill said. "I mean, we always had fans on the road -- we had a big following, there's no doubt. But there were always the haters out there, and [after 9/11], it didn't feel like that. In other cities, it felt like the country was rooting for us because they needed something to take their mind away from things for a few hours a day."

Players sensed the outpouring of support, holding no illusions that it reflected less upon their on-field exploits and more upon the activities of the police, firefighters and rescue workers still digging through the smoldering hellscape of what used to be the Twin Towers. The ever-present danger of more terrorist attacks -- including incidents of mailed anthrax -- kept the nation on high alert.

"What I remember of those days," Mariano Rivera said, "is that the whole country got together. That's a beautiful thing. I wish it was still like that, but it's not. The whole country, the whole U.S. got together, and it was amazing. Everybody helping everyone, it didn't matter what race or color you were. We were here for one nation and fighting, trying to move forward. And that's exactly what we did."

Torre addressed his players on the eve of the postseason, intoning, "We’re not only playing for New York, we’re playing for the rest of the country.”

Matched against a Wild Card-winning A’s team, whose construction was later detailed by Michael Lewis in the best-selling book “Moneyball,” the Yankees dropped the first two games of the AL Division Series at Yankee Stadium. Heading west needing to win out in the best-of-five set, they did precisely that, with Jeter’s iconic “Flip Play” in Game 3 shifting the series’ momentum.

In the AL Championship Series, the Yankees faced the Mariners, who’d established a Major League record with 116 victories in the regular season. Seattle wasted its home-field advantage as the Yanks secured the first two games at Safeco Field, then New York recovered from a Game 3 blowout in The Bronx to take the final two contests and win their fourth straight pennant.

The crowds packed 50,000 strong into the House that Ruth Built were electric, but the players’ celebration seemed muted: a few toasts with champagne poured into plastic glasses within the clubhouse walls. George M. Steinbrenner visited to take in the scene that night, the team’s principal owner remarking to reporters that the pennant was “as good as any we've ever won."

"You've got to remember the emotions that these fellas have been under,” Steinbrenner said then. “You live in this city and you watch it every day on television. To see that gaping hole and those buildings are gone, nobody has to perform under pressure the way these fellas did. And I'm glad for New York."

Matched in the 97th World Series, the Yankees and D-backs presented an exhibition in contrasts -- the storied navy-blue franchise of Ruth, Gehrig and DiMaggio against an expansion franchise in its fourth year of existence, resplendent in purple-and-teal uniforms and playing home games with a swimming pool in right field of their retractable-roof ballpark.

The D-backs may not have possessed much history, but they had two aces in Curt Schilling and Randy Johnson, whose gifted arms helped boost Arizona to a 2-0 Series lead. The Series shifted to Yankee Stadium, some nine miles north of where spotlights still illuminated wreckage nightly, work pausing for any new grim discoveries.

Clad in an FDNY fleece that hid a bulletproof vest, President George W. Bush loosened his arm in the batting cage hidden below the first-base grandstands, preparing to toss a ceremonial first pitch. Under fluorescent lights, Jeter eyed the president and remarked, “Don’t bounce it, they’ll boo you.” Bush laughed, then accepted Jeter’s advice.

With snipers intently watching from the Stadium roof and a Secret Service agent taking the place of home-plate umpire John Hirschbeck, the one-time managing general partner of the Texas Rangers anchored his right foot to the pitching rubber. Bush fired a strike to backup catcher Todd Greene in what he later called “the most nervous moment of my presidency.”

“I was running sprints with Scott Brosius in the outfield, and we just stood still,” O’Neill said. “New York in October, it’s dark and lit. When the president walked out, I thought it was one of the most awesome things I’ve ever seen. But I remember being so relieved when he was off the field.”

The Yankees took Game 3 by a 2-1 score, setting the stage for a memorable Game 4, played on Halloween. Arizona manager Bob Brenly called upon closer Byung-Hyun Kim for a six-out save. The Yankees got to the right-hander in the ninth, when O’Neill lined a one-out single before Tino Martinez launched a game-tying two-run homer into the bleachers in right-center field.

With the game headed for extra innings, the clock ticked past midnight. The Stadium scoreboard read: “Welcome to November Baseball.” Rivera shut down the D-backs in the top of the 10th. Jeter batted third in the home half of the frame, connecting with a full-count slider for an opposite-field homer that lifted the Yankees to a 4-3 victory. “Mr. November” was born.

"We'd been a part of a lot of big games over the years, but that was probably the loudest I heard Yankee Stadium," Jeter said. "It just goes to show you that sports plays a big role in the healing process for communities.”

Now the Series was tied for Game 5, and it was all Arizona until the end. The retiring O’Neill doffed his cap and wiped tears as chants of his name ringed the ballpark during the ninth inning, fans believing it would be “The Warrior’s” final inning in the Stadium outfield. The memory still produces goosebumps for O’Neill, and there was more magic in store.

Kim returned to the mound, assigned to protect a two-run lead. Posada opened the inning with a double, and two outs later Brosius hit a pitch over the left-field wall -- the second straight night with a game-tying Yankee homer in the ninth. Alfonso Soriano ended the game with a run-scoring single in the 12th; there was bedlam at 161st Street and cheers at Ground Zero, where John Sterling and Michael Kay painted the word picture through crackling AM radios.

The whole country, the whole U.S. got together, and it was amazing. Everybody helping everyone, it didn't matter what race or color you were. We were here for one nation and fighting, trying to move forward. And that's exactly what we did.

Mariano Rivera

“Looking back,” O’Neill said, “I don’t remember losing the Series as much as I do winning those three home games, watching the crowds and watching people come together. Those were three of the most unbelievable games that I had the pleasure of playing. The flags, hugging during home runs, the closeness. All of a sudden, New York felt like a small town where people were together and just cared about each other. I remember losing in ’97 to Cleveland and being absolutely crushed all offseason, but I wasn’t in 2001. The coming together of New Yorkers was probably more important than who won the World Series.”

Game 5 was the Yankees’ final victory of 2001. A flaw in Andy Pettitte’s delivery tipped pitches to the D-backs’ hitters in Game 6 at Arizona; clad in a replica pinstriped jersey, the 11-year-old Cole recalled being pelted with peanut shells by emboldened D-backs fans while reliever Jay Witasick bore the brunt of an eight-run third inning. Game 7 featured the third ninth-inning comeback of the Series, with Luis Gonzalez breaking his bat on Rivera’s famed cutter to float a soft single over the drawn-in infield, chasing home Jay Bell with the deciding run. It was, as journalist Buster Olney later titled his terrific book delving inside that pinstriped era, “The Last Night of the Yankee Dynasty.”

Even in defeat, for the Yankees, there was a silver lining, as Rivera recalls the team's ability to help the city heal as “a blessing.”

“To me, that's the best World Series we played,” Rivera said. “We fell short, but we did everything in our power to win the World Series and give New York what they deserved. To me, that's the satisfaction. There was satisfaction, even though we lost. Because we fought."