Yankees Magazine: Winning Team

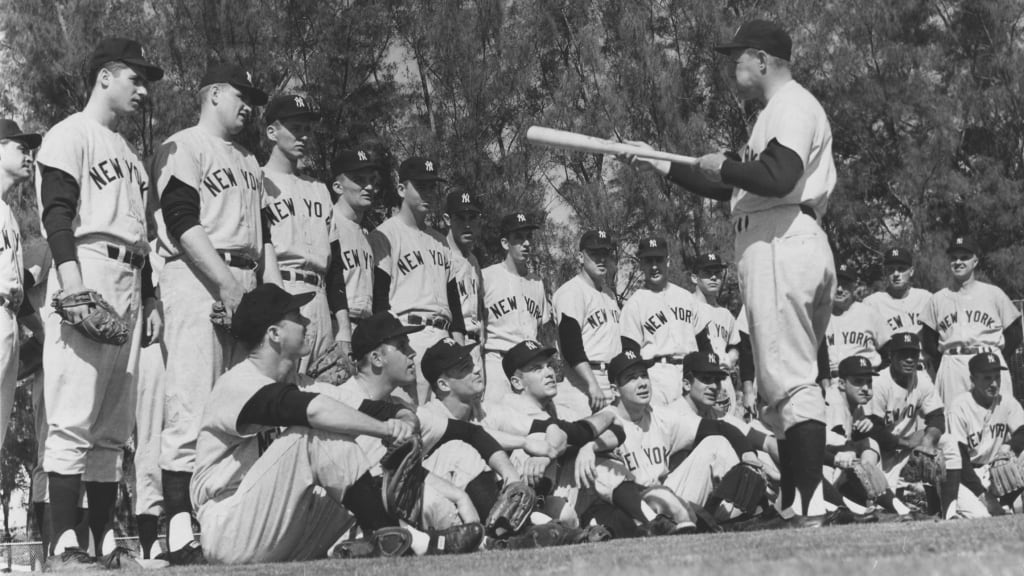

The 1961 Yankees were so much more than just the M&M Boys

The funny thing is, there never even was an asterisk. In 1961, when New York Yankees teammates Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris embarked on their epic home run chase to break Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs in a season, Major League Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick was in a bind.

Fiercely loyal to the god-like Ruth, Frick needed to come up with a solution that would both appease the slugger’s family while also acknowledging that 1961 was the first year of the expanded schedule -- which gave American League players eight extra games to pad their statistics.

Or break a cherished record.

But as the legendary New York City sportswriter Phil Pepe wrote in his 2011 book, 1961*: The Inside Story of the Maris-Mantle Home Run Chase, Frick merely ruled that there would be two entries in the baseball record book. One entry was for records set during the 162-game season, one entry for milestones reached during the 154-game seasons. The asterisk, Pepe wrote, was a myth, subsequently perpetuated by the press, fans and screenwriters.

Héctor López likes the idea of an asterisk, though.

“Looking back on ’61, maybe the whole team should have gotten an asterisk because that was just a phenomenal team,” says the former Yankees outfielder, who turned 92 in July and lives in Florida. “Roger and Mickey got all the headlines, but we had a team that was almost perfect -- a great starter at the top of the rotation, a great staff, great relievers, great defense and, of course, we could hit. We had contributions from everybody.”

Maybe López is right. As we look back at that championship-winning team 60 years later, perhaps an asterisk should be attached to the squad to symbolize how much more there was to the 1961 New York Yankees than Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris and the ghost of Babe Ruth.

***

You can’t talk about 1961 without first talking about 1960. After missing out on the World Series in 1959, the Yankees traded for a young outfielder named Roger Maris that offseason. All Maris did in his first year in pinstripes was hit .283 with 39 home runs and 112 RBIs, earning American League MVP honors while leading New York to a 97-win season, the AL pennant and a berth in the World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

“People forget that Roger was a good player, a complete player, and that he won the MVP the year before he hit the 61 home runs in ’61,” says former Yankees pitcher Ralph Terry from his home in Kansas. “1960 was a fun year, but it didn’t end fun, I can tell you that. Especially for me.”

The World Series that year is etched in lore. The underdog Pirates won the title, 4 games to 3, when Bill Mazeroski led off the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7 with a home run off Terry to give Pittsburgh a 10-9 win.

“People have heard those stories about Mickey crying in the locker room after the game, and they’re true. They’re all true. We were all crying,” says Bobby Richardson, the venerable second baseman who was named Series MVP that year with a record 12 RBIs. “All Mickey kept saying was, ‘How do we score that many runs and kick the [crap] out of them and lose the Series?’”

Indeed, the Yankees outscored Pittsburgh over seven games, 55-27, still the biggest disparity of runs scored and runs allowed for a losing team in World Series history. The Bombers won their three games 16-3, 10-0 and 12-0, while the Pirates’ first three victories were by scores of 6-4, 3-2 and 5-2.

“That left a bad taste,” Richardson says. “We were ready for 1961.”

But there was one more bit of housekeeping to 1960 that set up the ’61 season -- manager Casey Stengel was let go. On Oct. 18, five days after Mazeroski’s home run, Yankees owners Dan Topping and Del Webb relieved Stengel of his duties. The owners cited a team-instituted mandatory retirement age; Stengel indicated that he was fired. Either way, it paved the way for Ralph Houk, then 41, to be promoted from coach to manager.

***

The 1961 Yankees season is remembered for the home run chase, a milestone year for Whitey Ford and 109 victories -- still the seventh-most wins in a single MLB season -- but what shouldn’t be forgotten is the fact that the Yankees were in a bona fide pennant race for virtually the entire year.

As the final day of August 1961 came to a close, the Yankees led the Tigers by just 1 1/2 games with a big three-game set at Yankee Stadium awaiting the two teams. The Tigers were a good young team -- of their eight position starters, seven were under the age of 30. The Yankees had seven players hit double-digit home runs in 1961; the Tigers had six, led by Rocky Colavito with 45 and Norm Cash with 41. New York had six pitchers with 11 or more wins; Detroit had five pitchers with 10 or more.

The importance of the three-game series was obvious -- first place was on the line -- but perhaps never more serious than as depicted in a scene in Billy Crystal’s 2001 movie, 61*, about the home run chase between Mantle and Maris. In the film, Mantle, Maris and backup outfielder Bob Cerv are all talking about the Detroit series when Cerv says, “If I have to undergo surgery [in the offseason], I could really use that $7,000.”

Or the amount of the winner’s share of the World Series.

“It’s not a lot when you think about it in today’s money, but it was a lot in 1961, I can tell you that!” López says with laugh. “I’ll never forget when I first came up, Moose Skowron said to me, ‘Hectór, no matter what you do up here, don’t mess with my World Series money.’”

Skowron had to like his team’s chances of a return to the Fall Classic by the time the weekend was over. Ford started the opener of the big three-game set against Detroit, matched up against Don Mossi in a game that the Yankees walked off 1-0 winners in front of 65,566 fans at Yankee Stadium. Terry beat eventual 23-game-winner Frank Lary, 7-2, in the Saturday game and Elston Howard’s three-run home run in the bottom of the ninth inning won the Sunday game, 8-5. (Mantle led off the inning with a game-tying solo homer, his 50th of the season.) The sweep propelled the Yankees to a season-high 13-game winning streak and put the Tigers on an eight-game skid. In less than two weeks, the Yanks went from 1 1/2 ahead to an 11 1/2-game lead.

***

Ralph Houk was most definitely not Casey Stengel, not that anybody could be. Stengel was one of a kind, as evidenced by his appearance, along with Mantle, as an, ahem, expert witness in the 1958 Senate Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee meeting in Washington, where he befuddled lawmakers with his “Stengelese.” As one example, when asked why baseball wanted the antitrust bill passed, Stengel said: “I would say I would not know, but would say the reason why they would want it passed is to keep baseball going as the highest-paid ball sport that has gone into baseball and from the baseball angle.” When it was Mantle’s turn to speak he was asked a similar question, and the slugger brought the house down when he quipped: “My views are just about the same as Casey’s.”

Stengel was a character, but he was respected. He was also rooted in his ways and believed heavily in the platoon system. Houk did not.

“Ralph was a big believer in the military and had a great trust in the discipline that the military had,” says Tony Kubek, the starting shortstop on so many great Yankees teams and a renowned national broadcaster in the decades after. “Ralph was regimented.”

Says Richardson: “I knew Ralph because he had been my manager at Denver in the Minor Leagues, and I hit real good for him. When he took over with the Yankees, he called me and said, ‘Bobby, you’re going to be my second baseman. Every day. Every game. I don’t care if you hit .100, .200 or .300, although I prefer .300.’ That meant a lot to me before the season even started. It took a lot of pressure off.”

Richardson made 706 plate appearances and appeared in every game in 1961. But Houk’s conversation with Richardson was far from the only notable impact he had before the season even started.

“[He made] big, big moves,” Kubek says. “Moves that would have been controversial today.”

For one, Houk moved Maris ahead of Mantle in the lineup, thinking that Maris would see better pitches with the Commerce Comet batting behind him, an idea that Mantle fully supported. The second move was for Houk to hire Johnny Sain -- who combined with Warren Spahn to form the great (if abbreviated) Braves staff that inspired the rhyme, “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” -- as the Yankees’ pitching coach.

***

It was a meeting at a basketball court, of all places, that helped solidify the relationship between new manager, new pitching coach and star pitcher.

“That offseason, Ralph and Johnny took Whitey to a Knicks game,” Kubek recalls.

It was there that they talked about Whitey going with one less day of rest in between starts in order to squeeze in a few more over the course of the season.

“Imagine trying that today?” Kubek says. “And they also asked him to change the delivery a bit on that big overhand curveball that Whitey had. Whitey was all for it.”

The rest, as they say, was history. Ford had never started more than 33 games in his first nine seasons; he started 39 in 1961. He had never won 20 games; at age 32, he went 25-4 with a 3.21 ERA and won the American League Cy Young Award. In fact, after going 12-9 in 1960, Ford went 99-38 from 1961 to ’65.

And, in another anomaly from 60 years ago, Ford -- “a better hitter than anybody thought,” according to Richardson -- even had a decent year at the plate in ’61, collecting 17 hits, 10 RBIs and 12 walks.

“Whitey wasn’t a bad hitter at all. I wasn’t a bad hitter, either,” Terry says with a laugh. “I tried to switch-hit one time, but they made me go back. They were afraid I was going to get hit by a pitch on my pitching arm. They said, ‘Just take care of the score from the pitching side.’”

Once back on the hill, Ford, Terry, Bill Stafford, Rollie Sheldon, Bud Daley, Bob Turley and the rest of the staff learned much from Sain. Kubek -- an infielder -- even gleaned information from the Yanks’ pitching coach about spin rate -- long before it became fashionable.

“It’s such a funny story, but I was watching TV with Johnny,” Kubek says. “It was one of those old TVs with the antenna, and it wasn’t working. Johnny was so ticked off that he broke the antenna off the back of the TV and jammed it into an apple he was eating.”

But it was like the apple dropping on Newton’s head. Sain then took a baseball and drilled all the way through it, and put the ball on a screwdriver.

“Johnny would then spin the baseball, and he would show us how it could spin with a sidearm curve or an over-the-top fastball,” Terry recalls. “He showed the pitchers, ‘This is what it looks like coming to the hitter.’ It increased our understanding of how pitches worked and how it looked approaching the hitter.”

***

In a season filled with extraordinary statistics, this one deserves another look: Reliever Luis Arroyo was 15-5 in 1961 with 29 saves. Every single one of the 65 appearances the left-hander from Puerto Rico made in 1961 was out of the bullpen.

But 15 wins … out of the ’pen?

“That was a combination of great talent and great fortune,” Kubek says. “When Luis came into a game, often we were behind and then we would rally. Or we would pinch-hit the pitcher spot and still rally. But Luis was very successful with that great screwball getting right-handers out. Luis knew how to use the field.”

“Oh, he had a fabulous year and did a great job for us,” Terry says, before adding with a laugh: “I followed Whitey in the rotation. He saved a lot of games for Whitey, and then he was tired out for me!”

But Ford always knew that getting 25 wins had a lot to do with Arroyo.

“After the season, when they presented the Cy Young Award to Whitey at a dinner, Whitey paid for Luis to come up and be a part of it,” Richardson says. “Whitey said, ‘Luis, I just want you to know how much you meant to me this year.’”

***

Six decades later, Hectór López is still proud to be a “Scrubini.” A fancier name for the B-team, Johnny Blanchard coined the term to describe the guys who didn’t play as much during the season.

“Look at the lineup we had,” López says. “I mean, we had six guys with 20 home runs or more. It was hard to crack that lineup. That’s why Johnny called us ‘The Scrubinis.’”

Although Maris and Mantle led the way with 61 and 54 homers, respectively, the Yankees were far from a 1-2 punch, boasting nine players with at least 10 doubles. And it wasn’t just the offense: It was a tough lineup to crack because of the defense, as well. Clete Boyer was superb at third base, Kubek and Richardson were outstanding middle infielders and Skowron had a lock on first base. Mantle had the speed to cover large swaths of land in center field, and Maris had an above-average arm in right field.

Blanchard saw his time spelling a 32-year old Elston Howard at catcher, so all that really remained was left field for López, who appeared in 93 games to help an aging Yogi Berra.

“The good thing is, nothing was really ever a surprise,” López says. “Ralph was very good about that. He would come to you the night before and tell you to get some good rest because you’re in tomorrow, so most of the time we knew when we were going to play. And it seemed like we had a doubleheader every Sunday, so that was always an opportunity.”

López played in four of the five games in the Yankees’ World Series victory over the Cincinnati Reds, including the clinching Game 5, in which he tripled, hit a three-run home run and drove in five runs in a 13-5 victory. López also hauled in an easy fly ball off the bat of Vada Pinson to clinch the Yanks’ 19th world championship.

He remains wistful over his eight years in New York, especially being part of that ’61 team.

“That team reminded me of the way baseball should be played,” López says. “Everybody played as a team. It was a great team, and we just wanted to win. People used to ask me about the Roger and Mickey stuff and saying that they hated each other, but they didn’t. They were roommates. The fans might have been pulling for Mantle because he was brought up a Yankee and Roger was traded in, but the team was rooting for nothing but a win. We played to win.”

This story appears in the August 2021 edition of Yankees Magazine. Get more articles like this delivered to your doorstep by purchasing a subscription to Yankees Magazine at www.yankees.com/publications.