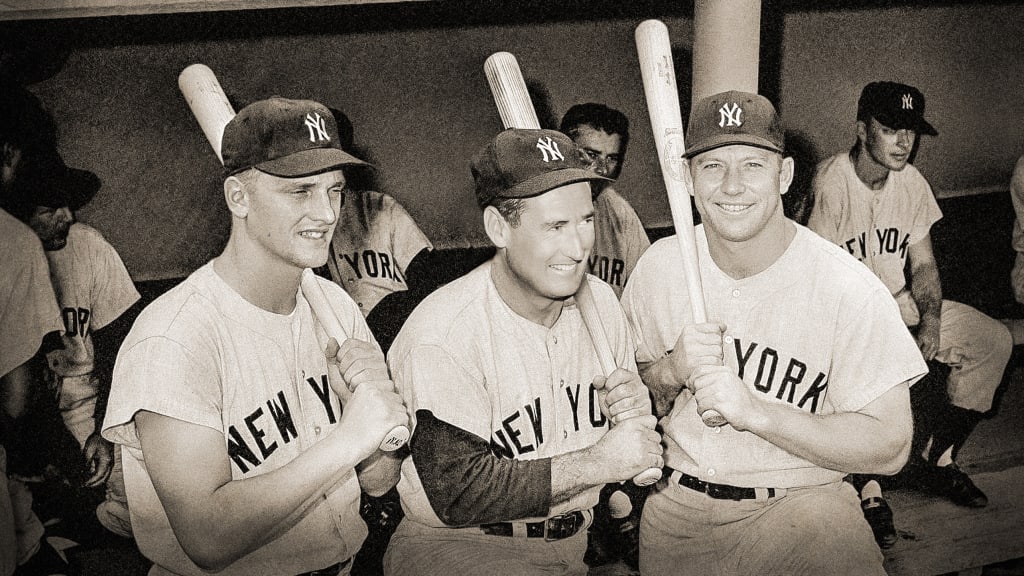

You’re probably already familiar with the story of the 1961 Yankees, of the Mickey Mantle / Roger Maris home run chase, of Whitey Ford’s 25-4 Cy Young season, of the 109 wins that rates among the best seasons in the history of baseball. Put it this way: You know it’s a memorable season when Billy Crystal makes an entire movie about it.

What you might not know, because we can admit that until recently we did not, is that if Yankee president Dan Topping had managed to get his way, there might have been something even more notable about that ‘61 team. It wouldn’t just have been the team of Mickey, Roger, Whitey, and chasing Babe for 61. It’d have been the team of Ted, too. Ted Williams.

If Topping had gotten his wish, one of the best lineups in baseball history would have also had one of the greatest hitters to ever live, bearing witness to one of the most memorable summers the sport has ever seen. He might have also accelerated the advent of the designated hitter to the American League by more than a decade.

As if the Splendid Splinter in pinstripes wouldn’t have shaken the baseball world enough, right?

On Sept. 28, 1960, at Fenway Park in the eighth inning of his 2,292nd and final game in the Majors, Williams hit his 521st home run, a moment so remarkable that the John Updike-penned recap (“Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu”) is arguably the greatest piece of baseball writing ever put to paper. The Red Sox went on to finish their season by dropping three to the Yankees in New York, but Williams, wanting to finish his career at home, wasn’t there. A month later, he turned down television jobs, unsuccessfully tried to purchase L.L. Bean, and mostly enjoyed a life of hunting and fishing.

Aside from a brief stint managing the Washington Senators/Texas Rangers franchise from 1969-’72, and occasional appearances as a hitting instructor at Red Sox camp, the baseball chapter of Williams’s career was closed.

So far as anyone knew, that was that. It wasn’t quite that simple, though.

“Nobody knew this, but the Yankees tried to hire me to play one more year in 1961,” Williams wrote in 1969. “Shortly after my last game, Fred Corcoran [Williams’ agent] got a call from Dan Topping, the Yankee owner, and they met at the Savoy Plaza in New York. According to Fred, Mr. Topping said, "Would Williams play one year with the Yankees, strictly pinch-hit for us for what he's making now -- $125,000?"

Relaying the story again in 1978, Williams then said it was an offer for two years, not one, although it’s a moot point, as Williams wasn’t interested. In the days before free agency, Williams would have needed Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey to relinquish his rights before he could negotiate with another team, though it doesn’t seem to have even reached the point of a discussion.

“I'm sure if I had wanted him to, Mr. Yawkey would have worked it out,” Williams said, “but I wasn't interested in playing for the Yankees. What did New York have to offer? A lot of bad air and traffic jams. I told Fred to forget it, not to promote anything, I wasn't interested, I was never going to hit another ball in a big league park.”

While Williams clearly didn’t have much positive to say about the five boroughs, the issue may have also been about what his role might have been on the 1961 Yankees, and that’s where we land on some fascinating baseball history. The 1960 Yankees were loaded with lefty outfielders, thanks to Maris (who won the MVP with what we now consider a 160 OPS+), the switch-hitting Mantle (40 homers, 162 OPS+), and Yogi Berra, who at 35 was still a solid hitter (118 OPS+) but was transitioning from behind the plate to the outfield. Each were returning to the team in ‘61.

Given that Williams would have been 42 and was already only a part-time left fielder in his final two years with Boston anyway, he would have been relegated to pinch-hitting, a role he had little interest in.

"Hell, no," Williams reportedly told Corcoran, as relayed in 1975. "You don't get any kind of batting average pinchhitting once a game."

By most standards, Williams’s career .297 average and .963 OPS as a pinch-hitter would be considered excellent. By his, it was a large step back from the .342 and 1.110 he’d had as a left fielder, which tracks well with recent research that shows batters wear about a 20% penalty when serving as a pinch-hitter. You can understand why it might not have been worth his effort to hold off on the fishing to take 150 or so plate appearances coming off the bench for the Yankees, with all the travel required for what would have essentially been about three minutes of work per night.

But: what if it wasn’t once a game? What if it were several times per game -- via a rule that didn’t yet exist? It helps, as it turns out, to have friends in high places: In this case, the president’s office of the American League, then occupied by Joe Cronin.

By 1960, Cronin’s association with Williams had been established for more than two decades, dating back to the day in 1939 that a 20-year-old Williams made his Major League debut with Cronin in the lineup as Boston’s shortstop -- a lineup Cronin had also written out as Red Sox player/manager.

They’d spend four seasons together as teammates, including Williams’ legendary .406 season, then two more with Cronin as field manager after Williams returned from service in World War II. In 1948, Cronin moved upstairs into an executive role, serving 11 years -- comprising most of the latter part of Williams’s career -- and in 1959, he left the Red Sox to become the president of the American League, a position he held through 1973. In 1984, when their numbers were retired on the same night, Williams said that "one of the great breaks I had in this game was that I got to play for a manager like Joe."

Williams valued Cronin’s name so much, apparently, that when Senators owner Bob Short was having difficulty getting Williams to return his calls about accepting the managerial job, he sneakily succeeded by leaving Cronin’s name on the messages along with Short’s own number.

When the designated hitter rule came into being in the AL in 1973, there was Cronin, defending it against all complainants. “The designated hitter rule is here to stay, I feel sure of it,” he said in the first week of the season. “I feel that this is a wonderful addition to the game.”

But while the DH was new to the Majors in '73, it was hardly a new idea. The roots of it had dated back to the 19th century, and it had been promoted numerous times over the years -- prominent cases including in 1906 by future Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack and National League president John Heydler in 1928.

Getting back to 1960, Williams's final year, Cronin had been president of the AL for two seasons. As Milton Richman, decades-long baseball writer and winner of the 1980 BBWAA Career Excellence Award, wrote in 1975, the DH idea had already been on Cronin’s mind by '60.

“American League President Joe Cronin began pushing an idea of his,” wrote Richman in his syndicated column, explaining how the Yankee offer for '61 had come to be. “Maybe he did it because Ted Williams was on the way out, and he had always liked the big, curly-haired kid. Why not have someone hitting for the pitcher everytime the pitcher was due up, Cronin urged. It would generate more excitement in the game, Cronin argued.”

As Cronin’s obituary in 1984 read, he “did not originate the designated hitter idea, but he was one of its strongest boosters when the rule proposal was made.”

It was an idea ahead of its time, and it was too soon. Cronin either didn’t have the support, or didn’t float it seriously, or didn’t think it could be incorporated that quickly anyway. (When it did come into existence in 1973, it had been tested in Spring Training over the previous four seasons.)

Judging by the attitudes of some players even in the 70s, you can imagine what an uphill battle Cronin might have found.

“It’s legalized manslaughter,” said Carl Yastrzemski, Williams’ successor in Fenway’s left field. “Batters will have to wear armored suits. The fact that pitchers have to take their times at bat is the only thing that keeps them honest.”

But Williams, who had said he wasn’t interested in sticking around to hit just once per game, said something entirely different about what he’d have done if he could have hit multiple times per game.

"That's different," Williams said. "Something like that would be fine, but I'm not interested in going to bat only once a game."

It might have finally been what completed a decades-long interest by the Yankees in Williams; the two sides had a long history together, and we’re not just talking about the 62 home runs he hit against them in 1,351 plate appearances.

New York scout Bill Essick had originally tried to sign Williams as a San Diego schoolboy in the 1930s, and there have been endless reports over the decades about a possibly apocryphal Williams-for-Joe-DiMaggio trade, usually described as taking place somewhere in the 1947-’50 range. (Speaking of DiMaggio, Topping had also offered him the same "please don't retire, just pinch-hit for us" arrangement they offered Williams.)

According to general manager George Weiss, who was the Yankee GM from 1947-’60, New York had tried to acquire him again in midseason 1959, with both Boston and New York in the midst of disappointing seasons. Had they talked him into it following the 1960 season, it would have been at least their fourth attempt in hiring Williams.

Regardless, Williams wouldn’t have been the first DH, since the Senators and White Sox had opened the 1961 season in Washington, D.C., one day ahead of New York’s season opener hosting the first game played by the Minnesota Twins. Perhaps Floyd Robinson or Earl Torgeson, who each pinch-hit for the visiting White Sox that day, would have been in the lineup as the first DH. Maybe the famous name of Ron Blomberg wouldn’t be quite so well-known today.

The ‘61 Yankees hardly needed Williams, of course, as they hit 240 home runs, a record that would stand until 1996. When the aging Berra didn’t play in left, right-handed hitters Héctor López and Bob Cerv did, though perhaps Cerv’s May 8 reacquisition from the expansion Angels wouldn’t have happened with Williams around.

But had the DH been available, there would have been room. Yankees pitchers that year took 499 generally-terrible plate appearances, posting a miserable-even-by-pitcher-hitting-standards .157/.199/.181 line that was the fourth-weakest of that year’s 18 teams. Whitey Ford was the largest offender, stepping to the plate a whopping 114 times and managing just 17 hits (all but one a single) and 12 walks.

If we can do some back-of-the envelope math here, and give all 499 of those plate appearances to Williams, how much better would the 1961 Yankees look? This is probably unfair -- at 43, even without having to play the field, he’s likely to have had a few days off, and it’s anyone’s guess as to how being a full-time DH would have agreed with him -- but let’s have the fun here.

If we take a weighted average of his final three years in Boston as a very simple look-ahead projection, we’d get a line of .304/.433/.559, a .992 OPS. That might undersell him a little, since it includes his career-worst 1959 when he had a .791 OPS due to a pinched nerve in his neck, but also he would have been 43 and needing to fly cross-country for the first time during a season, with the Angels entering the league, so we’ll go with it.

It doesn’t take very many math degrees to know that a .992 OPS (Williams’ simple weighted 1961 projection) is better than a .380 OPS (what the Yankees pitchers actually hit that year.) If we take the team’s actual overall .771 OPS and replace those 499 terrible pitcher plate appearances and replace them with what Williams might have done, that jumps the team’s production all the way up to a .795 OPS, along with 27 more homers. (Possibly even more, if you believe in the short porch, though the effect of that is generally overstated.)

The then-record 240 homers would have become 267, a mark not touched until 2018.

Many years later, Williams disapproved of the DH idea entirely, saying that he “liked it at first, but now I think it has taken something away from the game, especially the strategy of a manager." We wonder how he might have felt if he’d been among the first to do it. We wonder if the National League might have been on board with the idea earlier if the American League had started it that soon.

We wonder, mostly, what one of baseball’s most magical summers might have looked like with a living legend looking on, offering advice, and pounding a few homers of his own.

Mike Petriello is a stats analyst for MLB.com, focusing on Statcast and Baseball Savant, and is also a contributor to MLB Network.