Jose Contreras, Jose Abreu, Yoán Moncada, Luis Robert, Yonder Alonso and Jon Jay walk into a conference room at Camelback Ranch on a Sunday morning in early March during Spring Training.

A bond has been forged between the group via the White Sox organization they work for, but there’s something deeper shared within these six men.

Contreras, Abreu, Moncada, Robert and Alonso were born in Cuba, but made their way to the United States. Jay is of Cuban descent, but was born and raised in the U.S. This is the White Sox Cuban connection.

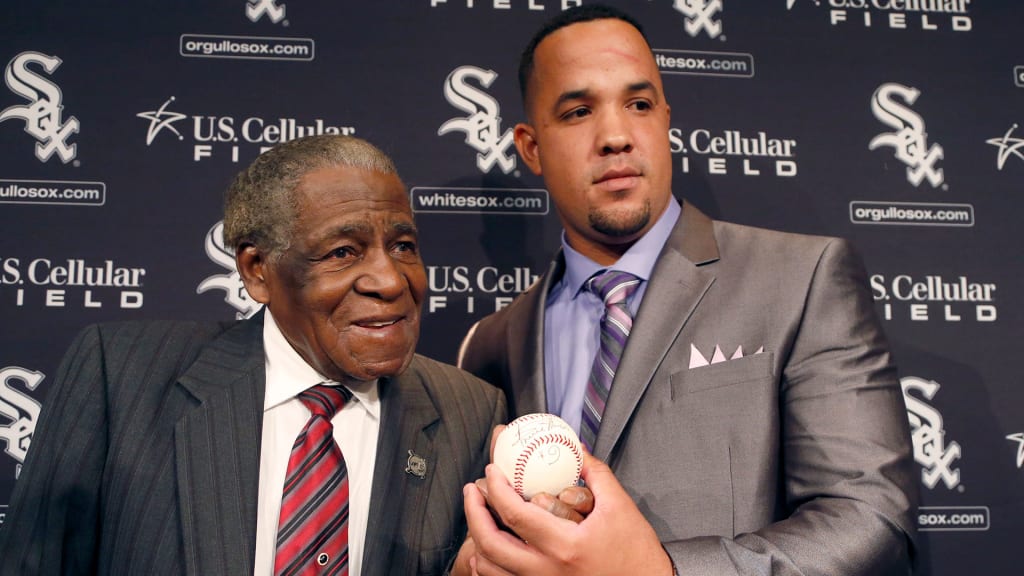

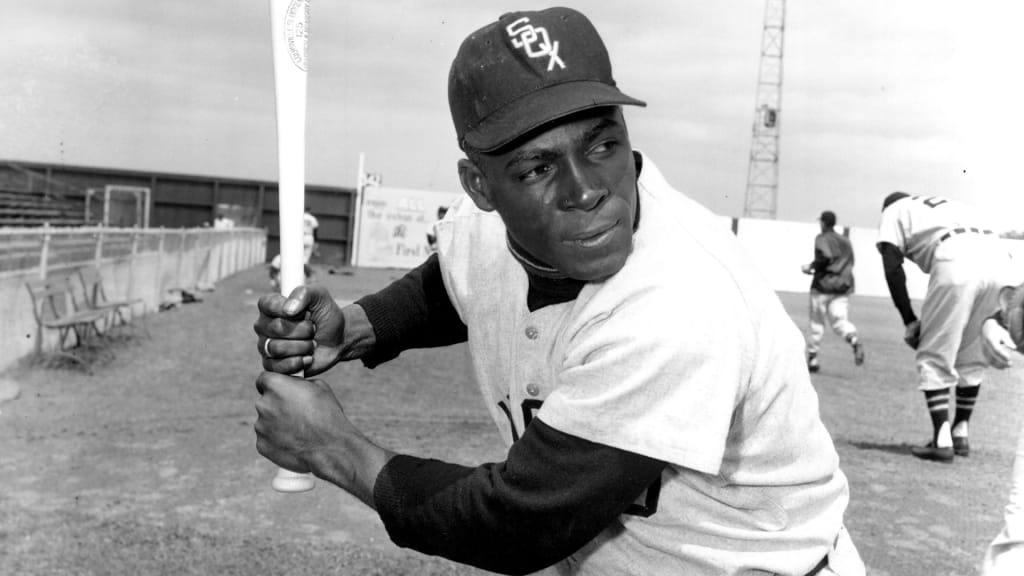

It all started, of course, with Minnie Minoso, one of the greatest players in the history of baseball not enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Minoso -- who in 1951 became the first black player to take the field for the White Sox and the first black Latino player in the Major Leagues -- played 12 highly accomplished years in Chicago. He was a gregarious fixture often seen at White Sox home games up until his death on March 1, 2015. He was a friend and mentor to Abreu, among the countless others whose lives he touched over the years.

In all, 20 players with Cuban heritage have played for the White Sox, not counting Robert, who has yet to reach the Majors, but appears well on his way. Robert, ranked by MLB Pipeline as one of the top 40 prospects in baseball, is tearing it up at Class A Advanced Winston-Salem after being limited to 50 games in 2018 due to a thumb injury.

When Robert arrives, he will continue the White Sox rich Cuban pipeline. And while a couple of franchises have had more Cuban-born players over the years (Twins, Reds, A’s and Angels), no club has seen Cuban players make a bigger impact on its franchise, culture and success than Chicago.

Minoso, as noted, is the one who started it all. And the franchise’s finest moment in recent memory -- the 2005 World Series title -- was made possible by two pitchers who defected from Cuba around the turn of the century -- Orlando Hernandez and Contreras. In fact, a picture of Contreras pitching in the playoffs sat up on the wall of the Camelback Ranch conference room where this interview took place.

Contreras was the de facto ace of that club, starting the first game in that year’s American League Division Series, the ALCS and the World Series, and posting a 3-1 record with a 3.09 ERA over the course of the 2005 postseason. He now serves as a special assistant to baseball operations.

Hernandez, aka El Duque, was a swingman who famously entered Game 3 of the ALDS against the Red Sox in the bottom of the sixth inning with the bases loaded and the White Sox clinging to a 4-3 lead. He calmly induced popups from Jason Varitek and Tony Graffanino before fanning Johnny Damon to escape the threat. He pitched two more scoreless innings -- including retiring Edgar Renteria, David Ortiz and Manny Ramirez in order in the seventh -- as the White Sox went on to clinch a series sweep.

The performances by Contreras and Hernandez resonated within their home country and with other Cubans who had Major League dreams. They were soon followed on the South Side by shortstop Alexei Ramirez, who defected in late 2007 and signed a four-year deal with the White Sox, as well as outfielder Dayan Viciedo, who signed a four-year deal a year later.

“Cuban players for some reason, one way or another, they landed here [with the White Sox],” Alonso says. “They’ve had big years. They’ve had big team wins. They’ve gone to the World Series. The whole country of Cuba is behind us. I think the whole country of Cuba is watching every single day what we are doing.”

White Sox GM Rick Hahn is definitely aware of the connection and thinks that the success in developing Cuban-born talent has been self-fulfilling.

“I would be lying if I said it was a purposeful strategy we embarked on a decade ago or so,” Hahn says. “Instead, we wanted to be as aggressive as we could be in all facets of player acquisition, including international. And there’s been a fair amount of Cuban talent available the last several years.

“We have a high level of confidence we can help these players and put them in a good position to succeed, but I think our history with these players resonates with them and makes us a preferred destination, all other things being equal.”

Kenny Williams, who is the club’s executive vice president and was the GM who built the 2005 World Series-winning roster, has perhaps played the largest role in deepening the franchise’s connection to top players from Cuban.

“We do have history on our side,” Williams says. “We do have players who speak positively of their experience here. And they are unafraid of expressing those opinions to players that happen to be available.”

The Cuban Connection

Baseball is a beloved national pastime in the United States. Kids play Little League, play in high school and some push on toward college with a dream of reaching the Majors. There are pickup games forming on local fields, empty lots or even in the middle of neighborhood streets. Kids are leaping into fences imagining they are Mike Trout or launching home runs followed by a trot akin to Aaron Judge.

Baseball has all that appeal in Cuba, too, but the feeling for the game, the need for it, goes much deeper.

“Baseball is life in Cuba. In Cuba it doesn’t matter if you have food or if you have clothes, for some people. But you need to be in love with baseball,” Contreras said. “Baseball is love. That’s something that you have in your heart. Here, it’s a little bit different, because it’s a business. But that’s one of the things I try to tell the guys here when they came over. You have to keep your passion, because baseball is everything else.”

When Contreras defected, in 2002, many of the country’s best players were still in Cuba, as the United States’ trade embargo had made it difficult -- and often unsafe -- for players to leave. He was considered the country’s best pitcher when he created a bidding war between the Red Sox and Yankees that ended with him signing a four-year, $32 million contract with New York prior to the 2003 season. And while other notable names had come a couple of years before him, such as El Duque and his younger brother Livan Hernandez, Contreras seemed to open the floodgates. He was soon followed by the likes of Kendrys Morales (2004), Yunel Escobar (2004), Aroldis Chapman (2009), Yoenis Cespedes (2011), Yasiel Puig (2012) and Abreu (2013), among many more.

Abreu’s six-year, $68 million deal with the White Sox is one of the largest given to a Cuban defector, but the Red Sox paid a similar price when they signed Moncada in 2015 to a deal that included a $31.5 million signing bonus. Because the Red Sox ended up exceeding their bonus pool allotment by $31.5 million, they paid a 100 percent tax on the overage, which means that Moncada cost Boston -- who would ultimately use the infielder as part of the trade package used to acquire Chris Sale at the 2016 Winter Meetings -- a total of $63 million.

Moncada has been a bright spot for the White Sox this year, including his first career multi-homer game on Tuesday, but also represents the talent drain that has come out of Cuba in recent years. The fact the Red Sox were willing to pay such a steep price for him was partially due to the fact that there are fewer players of his caliber coming out of Cuba.

“Years before in Cuba, baseball was more intense,” Moncada says. “Right now, it’s probably not as intense as it used to be and probably the quality is not what it used to be, either. But we still have plenty of talent there and baseball is very special."

One of those special talents who arrived more recently is Robert. He received a $26 million bonus from the White Sox in 2017, and has been the most dominant player in the Minor Leagues this season. Through his first 12 games for Winston-Salem, the 21-year-old outfielder was hitting .471/.518/.902 with 5 homers in 51 at-bats.

“That’s every kid’s dream, just to play baseball in Cuba,” Robert said. “When I was a kid, I was able to go to some games. I was in the stands and just dreaming to be on the field and be one of the guys I was watching at the moment. When I had that opportunity, it felt very special to me. Baseball is life. Baseball is everything for all of us in Cuba. It’s very special just to play baseball and be a baseball player in Cuba.”

Coming to America

Alonso’s story is a bit different than the others, in that he came to the U.S. as a 10-year-old, with his family’s move not driven by a baseball career. He immediately took in new everyday experiences, things many people often take for granted.

“It’s funny, the first time I came from Cuba, they took me to McDonald’s,” says the first baseman. “I’d never seen ketchup or even the air conditioning or the smell. Then they took me to K-Mart because we had no clothes, we had nothing.

“I remember walking in through the sliding doors, and it was like I’ve never seen anything like these sliding doors. And then the smell, I just remember the smell in every house I would go to, the air was different.”

Playing baseball in America also was very different for a young Alonso.

“Every kid had two bats. Every kid had a helmet,” Alonso said. “Every kid had a glove. Every kid had new cleats. We didn’t have the money for that. My dad was ‘Borrow a glove. Borrow a bat. Borrow some batting gloves.’

“For me, the game in Cuba makes you a man at a very young age, because you play with the heart, you play with what you got and you play for the love. Once you get here, obviously things are a little bit on the easier side, but again you are still a boy with big dreams and playing a man’s game.”

Alonso eventually made his way to the University of Miami, where he and Jay were teammates. The two have a deep friendship that began long before their stint as teammates this season.

Abreu and Contreras, on the other hand, arrived in the United States as baseball stars with the expectations that come with a big contract. Their transitions to Major League life were a bit different.

“I’m from a very small town in Cuba where I didn’t have any electricity or power in my house,” Contreras says. “I earned 75 cents per month when I was there. Then when I signed with the Yankees and I came over, it was like ‘Wow.’ I couldn’t believe all the awesome things that I was seeing here. And I was in New York. There are some things you can’t describe. You can’t put into words.”

Abreu paints a similar picture.

“Sometimes we talk about this experience and we still can’t believe it,” he says. “We can’t believe we are in one of the best countries in the world, especially coming from where we all came. It’s kind of different. It’s indescribable.”

Team in transition

For now, three years into a rebuild, the word “championship” is not yet part of the White Sox vernacular -- but that doesn't mean these guys aren't already thinking about it. Moncada, Abreu and Alonso are contributing at the big league level, Jay is recovering from a right hip/groin injury, and Robert might arrive as soon as the 2020 season.

“I want to play with all the Cubans from Cuba,” Robert says. “To have the opportunity to play with countrymen here and to have a chance to win a championship it would be very special for me, like a dream come true."

Ultimately, it’s uncertain whether these five will be together when the White Sox become contenders, let alone champions. Abreu is in his last year of his contract, Jay is on a one-year deal and Alonso has a $9 million dollar option for next year. But it would mean something special to this group winning a title for the White Sox and for their native country.

“It would be a dream come true,” Jay said. “I was born in the States, so it’s a little bit different from everyone else. I kind of get sometimes ‘Oh, you are not full Cuban.’ But in my heart, my culture is Cuban. I was raised Cuban, my grandparents sacrificed a lot for me. For me, personally, it would be something that’s amazing. I’ve never got to play with so many Cuban players which, like I said, it’s amazing.”

It is Moncada who perhaps sums it up the best: “To win it with the five of us playing, it would be very special for us. That’s the dream.”