A version of this story originally ran in November 2021.

Ron Necciai, now 89 years old and living in Florida, almost seemed amused that I, and others, still want to talk about an unreal game he pitched back in 1952.

"I still get cards, letters and pictures to sign," Necciai said over the phone. "Yeah, surprisingly. It's unbelievable. I haven't played in 70 years."

I mean, Necciai really can't blame anybody for reaching out. Seventy years ago on this date, he pitched one of the more ridiculous games in organized baseball history.

The Pirates Minor Leaguer, at just 19 years old, struck out 27 batters, while giving up no hits, in a regulation nine innings. It's the only time that's ever been done at the professional level.

Necciai was as shocked as anybody that he pulled it off, always thinking he was too wild to ever have success on the mound.

"I called myself a thrower," Necciai told me. "It was marked 'P' on the program, but I was never a pitcher."

-------------------------------------

Necciai's foray into pro baseball began just two years prior to that May 13, 1952, game. And he's right, he was a bit wild off the mound. The right-hander split limited time between the Salisbury Pirates and Shelby Farmers -- putting up a 21.00 ERA and infinity ERA, respectively.

"I either walked them or struck 'em out," Necciai said.

The next year, Pittsburgh GM Branch Rickey sent Necciai to Double-A New Orleans to work on his control. The manager there, Rip Sewell, was an ex-big league pitcher -- although he was more known for inventing the crawling, fluttering eephus pitch to revive his career. An interesting choice to help a young pitcher trying to tame his fastball.

"Rip Sewell wasn't any help, as far as I'm concerned," Necciai told me, laughing.

Although, according to Necciai, Sewell did sum up the young pitcher's repertoire pretty well at the time.

"Rip used to tell 'em, 'He had two pitches: No. 1, knock 'em down and then give him Uncle Charlie,'" he recalled. "Knock 'em down and then throw them a curveball. I could knock 'em down without trying and I had a [bad] curveball."

Even after more control problems in '51 (129 BB in 139 IP), the Pirates organization felt Necciai was still very young and not worth giving up on. Newspaper reporters had coined him with the nickname "Rocket Ron" because of his blazing fastball. Rickey was already calling him the next Christy Matthewson or Dizzy Dean.

Necciai was invited to Pirates Spring Training in San Bernardino in 1952, but stomach ulcer problems, something he'd dealt with his entire life, were becoming a big issue. He went to see a doctor, was off for some time, and then Rickey -- taking into consideration his starter's health issues -- asked him where he felt comfortable playing that season. Necciai wanted to play under his manager from his time in Salisbury, George Detore, and so he was sent to Detore's new team in the Appalachian League in Bristol, Va.

Necciai suddenly caught fire for Detore's team. He struck out 20 batters in his debut, while only walking four. He sat down 19 in another game, and K'd 11 of 12 in a relief role three days later.

Still, as much as he was accomplishing on the field, Necciai was struggling mightily with his stomach. Even the night leading into his historic May 13 start (and, frankly, most of that day), he had pains running up and down his gut.

"I was taking all kinds of medications for cramps in my stomach," Necciai said. "My stomach was bothering me that night, believe it or not."

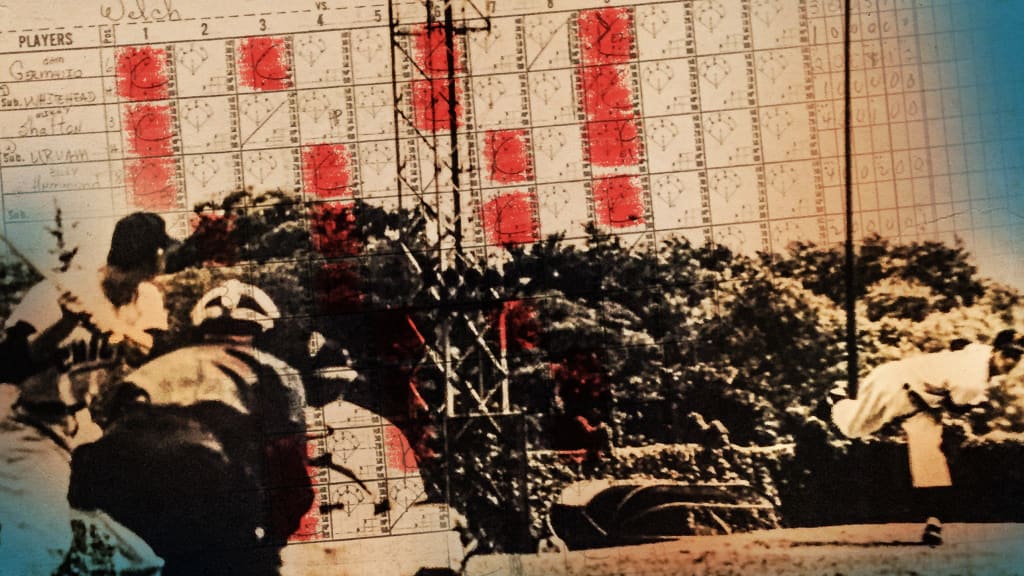

So, while swallowing some weird black pills, chugging milk in between innings and dealing with intense abdominal pain, Necciai pitched that May night like he was from another planet. The Welch Miners mustered a walk, a HBP and reached on a dropped-third strike and error, but went down on strikes a record 27 times. The previous mark had been 25. Necciai still has the K-heavy scorecard to prove it wasn't a dream.

Necciai, incredibly humble (he didn't even tell me about all the other success he had that season; I had to look it up), said he didn't fully realize he had struck out 27 until after the final out. He also doesn't remember anything specific from his performance, mostly just crediting his catcher and manager for calling a great game.

"Yeah, I mean when you hit a guy and walk a guy and there's an error, there's a lot of action," Necciai said. "I wasn't really paying attention to what was going on. I paid more attention to try and throw strikes."

"He was just awesome that night, they couldn't hit the thing," catcher Harry Dunlop, who was 18 to Necciai's 19 at the time, told me over the phone.

Dunlop, who caught in the Minors for 14 seasons and then coached in the Minors and Majors for five decades, said Necciai had some of the best stuff he'd ever seen that year.

"We didn't have guns in those days but he threw harder than anybody I caught over the years," he said. "He had a curveball that was like a split-finger -- it had that old-fashioned drop."

Dunlop said Necciai must've thrown close to 200 pitches, and also confirmed his batterymate's wild side was still very much part of the epic performance.

"It was ... it was work," Dunlop laughed. "I was blocking balls all night long, as you can imagine. ... A lot of 3-1, 3-2 counts. Not too many 1-2-3 and you're outs."

Necciai apparently hit the first batter in the fourth, then the error happened in the ninth -- as did the dropped-third strike, which gave Necciai the opportunity to strike out four in the final frame and get to 27. Welch batters were reportedly bunting at balls in the latter innings, but still somehow missing pitches.

As far as Dunlop realizing that history was happening, he says he did figure it out in the sixth or seventh inning when the crowd started counting from the stands.

"Hey, he's striking out every guy," the catcher remembered thinking. "I said, 'Oh my god.' I really didn't realize it. He'd gone so deep into so many counts and all I was thinking about was doing the job and getting my pitcher through the game."

But nobody told Necciai, maybe afraid he'd lose his focus.

The press descended on the teenager the next morning, but it definitely wasn't as big a story as it might be today.

"No big deal," Necciai told me. "It was in the Minor Leagues, you know."

And then, in his very next start, Necciai struck out 24 in nine innings. That's 51 strikeouts in two games (for comparison, in 2019, Gerrit Cole struck out 55 ... in four games). That's 25.5 K's per nine.

"Correct," Necciai laughed, when I asked him if he did indeed set down 24 in his next game.

"His fastball exploded on you," Dunlop remembered. "The breaking ball ... if he stayed healthy for a long time, God knows what he would've done."

After that start (and after striking out 109 hitters in 43 innings), Necciai was called up to the Carolina League, where he continued to decimate batters. He struck out a league-high 176 hitters in just two months.

"Did real well there," Necciai said, finally, kind of, crediting himself with being a good pitcher. "Led the league in strikeouts, earned run average. I made the All-Star team, I don't know why."

Finally, in August of '52, he was called up to the bigs. The 20-year-old quickly found out the difference between the Major and Minor Leagues. Hitters were much more patient and aware of the strike zone. The rookie went 1-6 with a 7.08 ERA, while putting up 31 strikeouts and 32 walks. He made his debut at hallowed Wrigley Field.

"When I could throw strikes, I got them out. When I walked them, it was catastrophe," Necciai said. "First day against the Cubs, I got bombed. ... You can't walk the world in the big leagues."

After that summer, Necciai was drafted to fight in the Korean War, but was quickly discharged because of his ulcer problems. While trying to get back into baseball shape, he tore his rotator cuff and lost that fireballing bite on his fastball. He pitched another season in the Minors in '55, but the injury was too much to keep going.

"I couldn't stand the pain," Necciai said. "And if I hit you between the eyes, you'd think a mosquito bit you or something."

So, at 23 years old, and a once bright baseball future already fading from view, a doctor gave him some advice he'll never forget.

"Son, go home, go buy a gas station. You're never gonna pitch again."

Necciai did go home, but instead got into the sporting goods business -- and was pretty successful. Talking with him now, he doesn't seem to have many regrets. He pitched one of the greatest games ever recorded on a baseball diamond and, unlike the majority of prospects, he realized his big league dreams.

"It's what every kid wants to do," Necciai told me. "I won one game, I had one base hit and drove in one run. ... I did it all. And nobody was more surprised in the ballpark than I was."

Matt Monagan is a writer for MLB.com.