The forgotten & amazing Latino All-Star Game

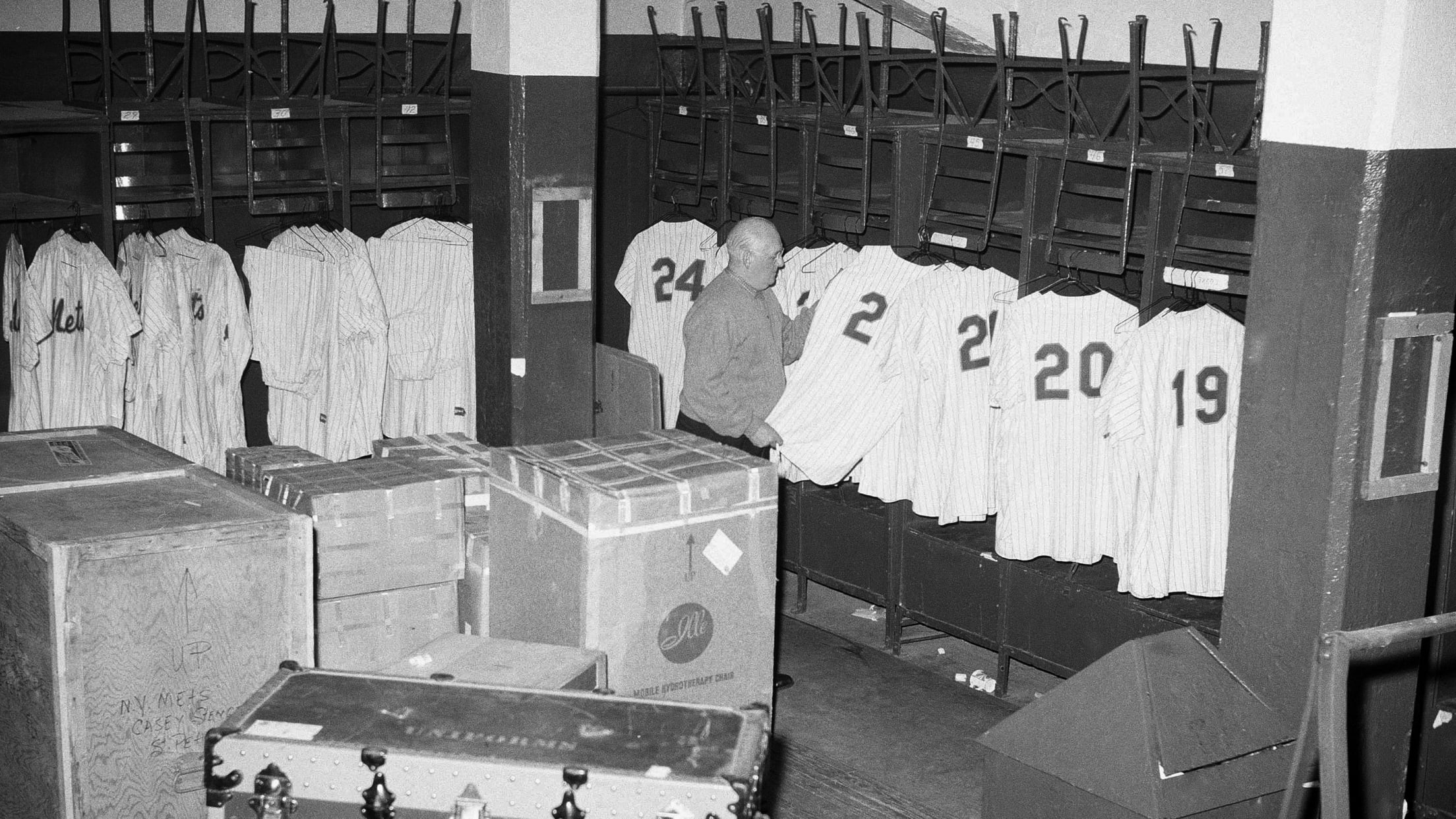

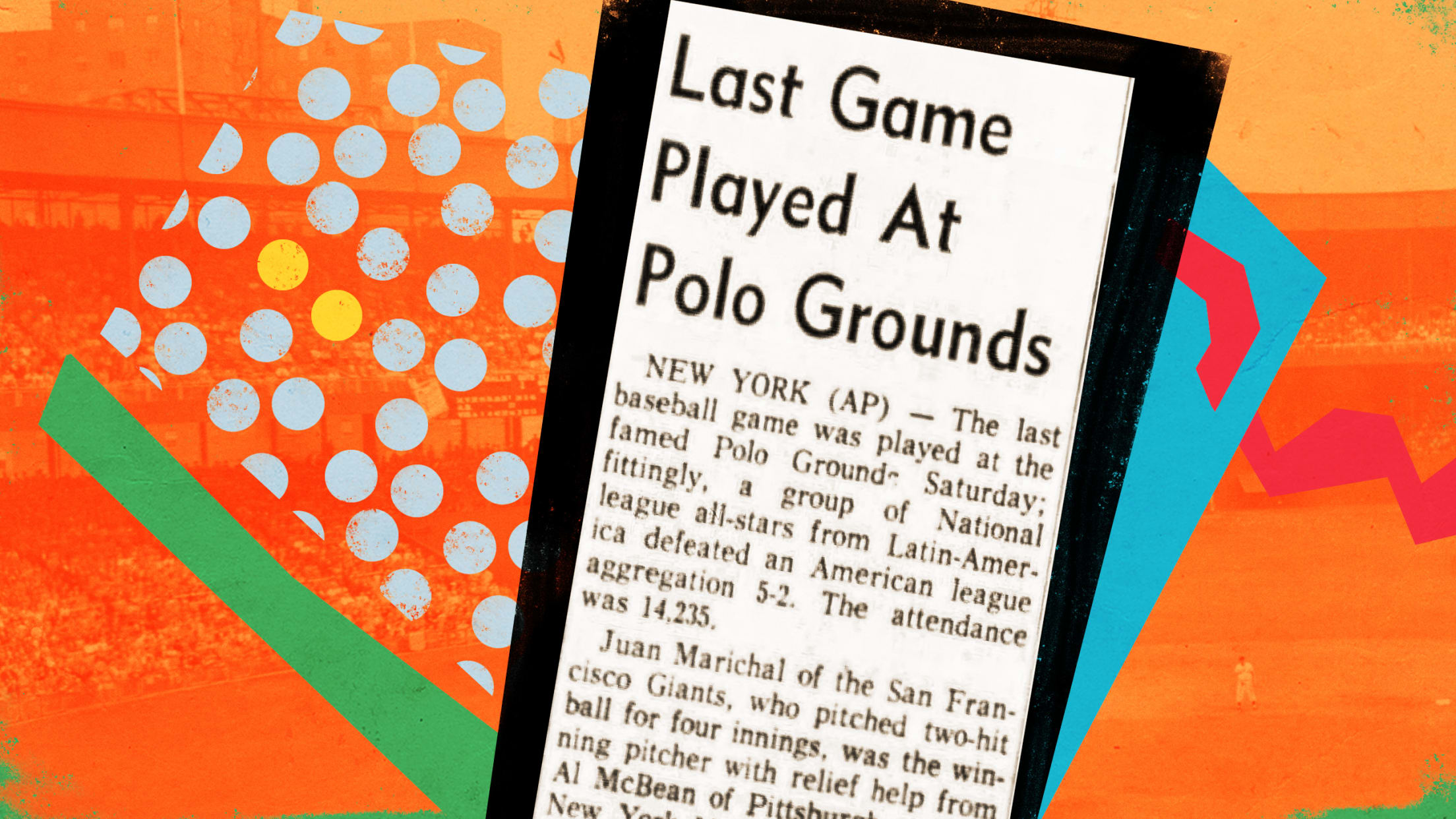

One week after the L.A. Dodgers swept the Yankees in the 1963 World Series, a group of baseball’s greatest players got together to play one final game at the storied Polo Grounds before it was torn down the following year.

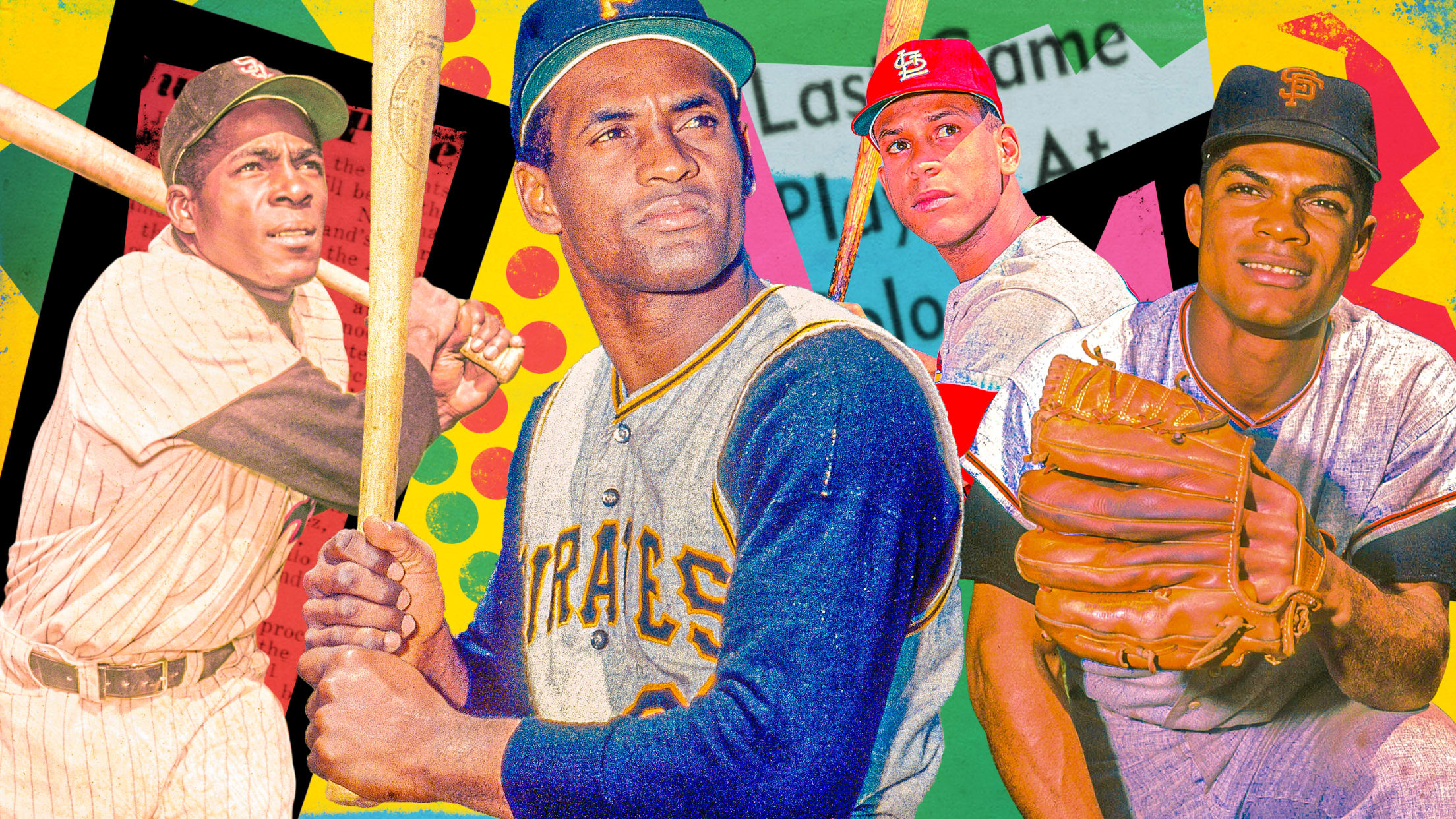

Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Minnie Miñoso and Juan Marichal. Felipe Alou, Vic Power, Zoilo Versailles and Tony Oliva. They're but a few of the legends who suited up that day.

The collective star power on the field for what was then called the Latin American Players Game, but is now referred to as the Latino All-Star Game, was so bright you couldn’t have fit them all onto a theater marquee if you tried. Yet, rather than this game being seen as the momentous and historic occasion that it deserves to be, it is almost an afterthought in history save for a few articles scattered around the internet. You may even find the Mets’ loss to the Phillies on Sept. 18 listed as the final ballgame at the Polo Grounds -- despite those early Mets teams barely scraping by as the definition of a "Major League" club.

Held on Oct. 12, the All-Star game raised funds for retired Latino players and the "Hispanic-American Baseball Federation" to provide equipment to youth players. It was also a true delight for New York's Latino community and for baseball fans at large. Renowned musicians and bandleaders Tito Puente and Tito Rodríguez, along with singer La Lupe, performed for the crowd of 14,235. While that may seem low considering the massive size of the 55,000 seat stadium, it's a far cry better than the 1,752 who showed up to watch that other final Polo Grounds game when the Phillies and Mets squared off.

A pre-game home run derby was held, with the American League defeating the NL, 2-1, thanks to home runs from Power and Hector Lopez against Alou's lone shot.

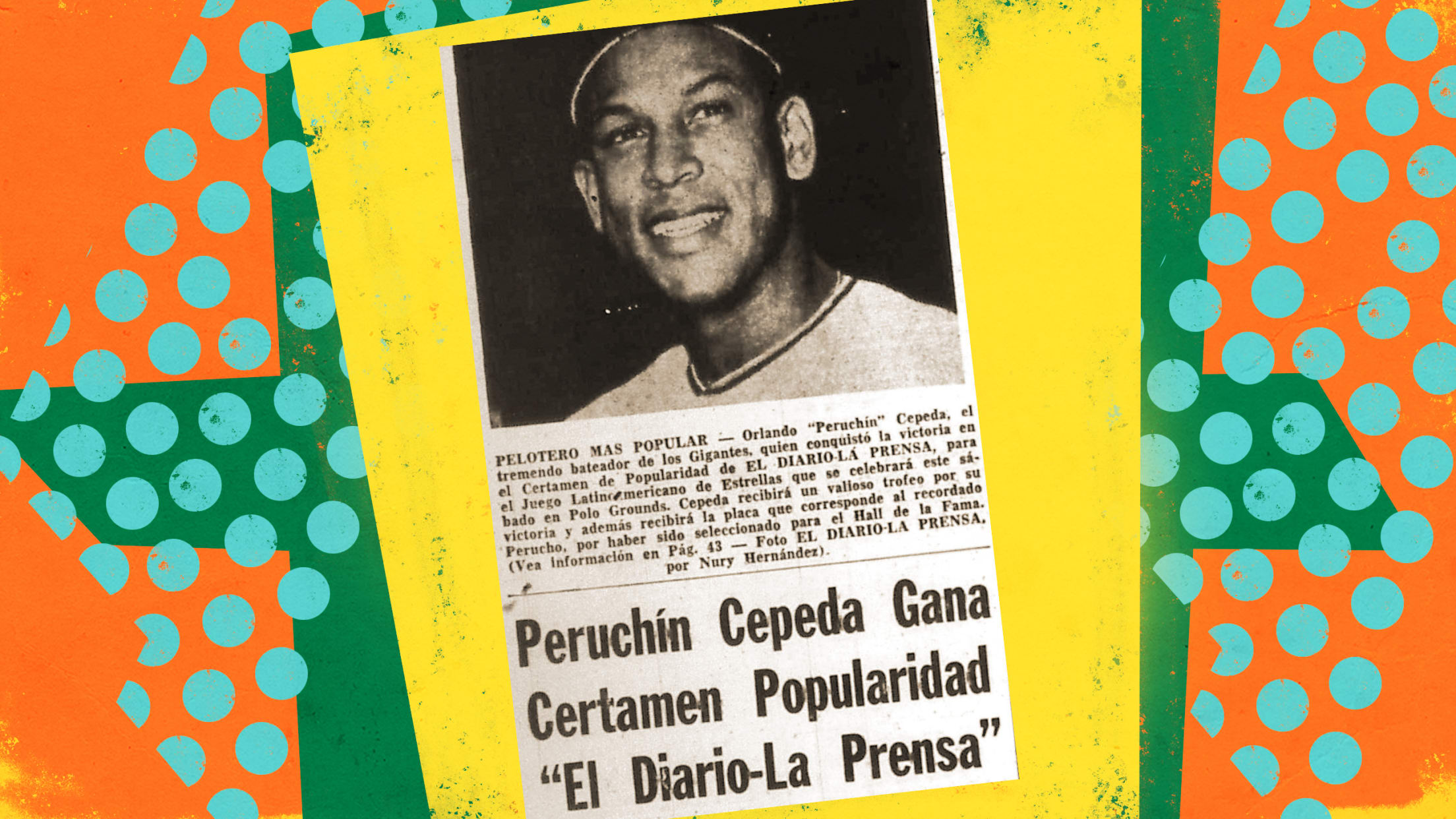

Awards were handed out, too. Power earned the title of baseball's "Best Latin player," while Marichal took the title of best pitcher and Cepeda was voted the most popular.

But this game wasn't just for the fans -- it was an equally important event for social reasons. The Latino ballplayer community was relatively small in the Majors at that time, and this game allowed them all to see each other, to spend time with each other away from the rigors of the regular season.

"I was very happy to all get together," Orlando Cepeda told me in a recent phone call. "For me to be able to participate and to spend some time together with so many great players like Roberto Clemente, Vic Power, Zoilo Versailles -- that was a great day. We had a great time, a really great time. We got together after the ballgame."

Of course, some players were a little hesitant. Tony Oliva, who was just 24 at the time and had all of 16 big league plate appearances to his name, did not go out with the group. It was his first time in New York City and he admitted that he was still very shy.

"I was afraid to do the wrong thing or anything," Oliva said. "I was very timid."

The Difficult Past

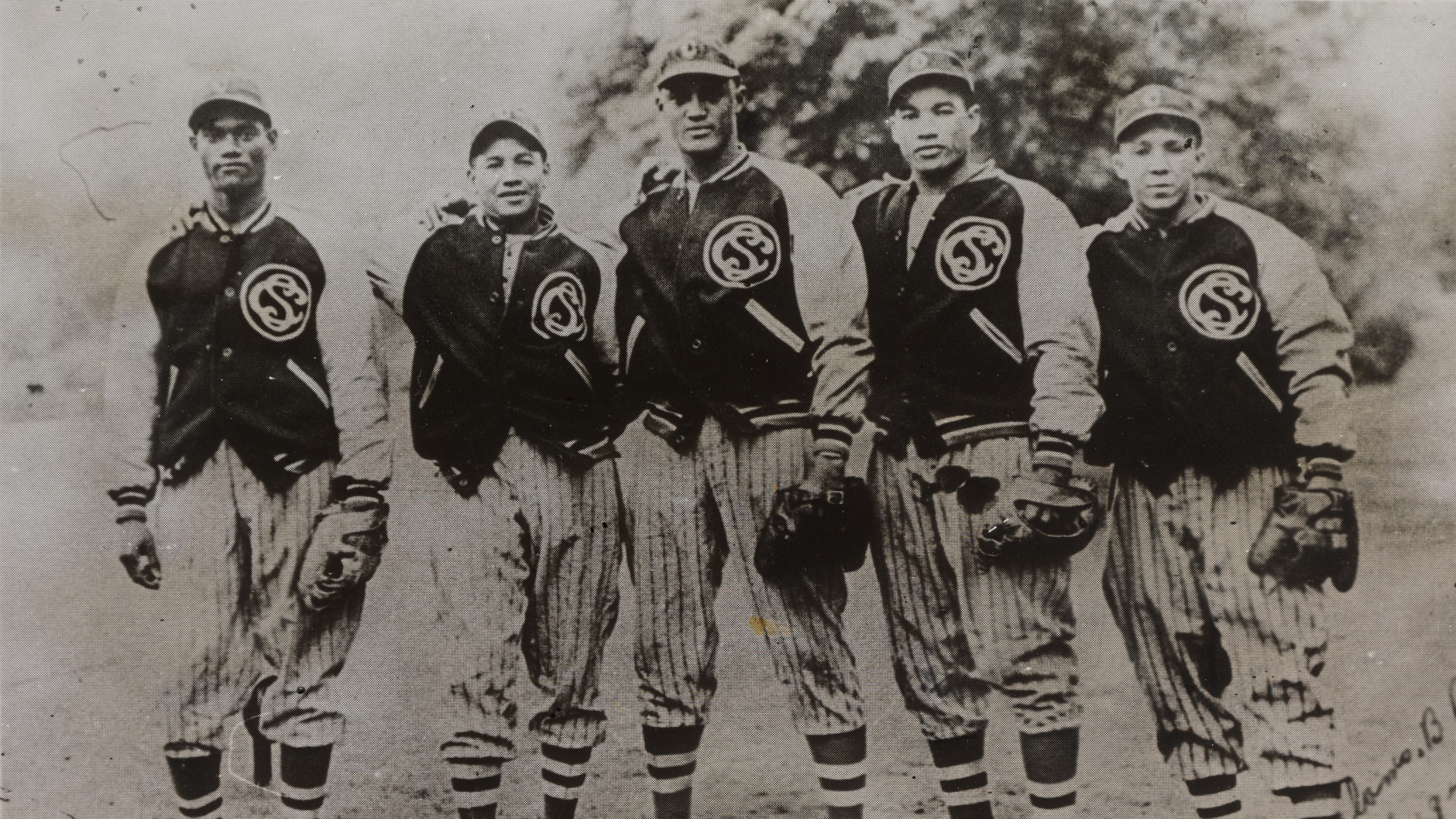

Latino participation in the Major Leagues stretches back long before this mid-century period. It goes back to the earliest days of baseball.

Adrian Burgos Jr., a professor of history at the University of Illinois, outlines this in his exhaustive look at Latino baseball history, "Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line."

"Latinos did not enter the U.S. playing field as simply black or white," he wrote. "Rather, most occupied a position between the poles of white (inclusion) and black (exclusion). First manifested in the racialization of Vincent Nava as a Spaniard and as a Spanish catcher in the early 1880s, this in-between racial position not only sustained the elevation of European whiteness but also revealed the Latinos' own differentiation from the white mainstream within organized baseball."

If you could pass as a "white" player, you were granted entry to the Major Leagues as Louis Castro was in 1902, or Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans did with the Reds in 1911. But if you didn't, you were given a choice to stay in your home country or play in the Negro Leagues until Jackie Robinson finally integrated baseball in 1947. This story often isn't told -- while 55 Latino ballplayers reached the Majors during the Jim Crow era, it's estimated that 10-to-15 percent of the players in the Negro Leagues were Latino, a number that ranges from around 350-500 players.

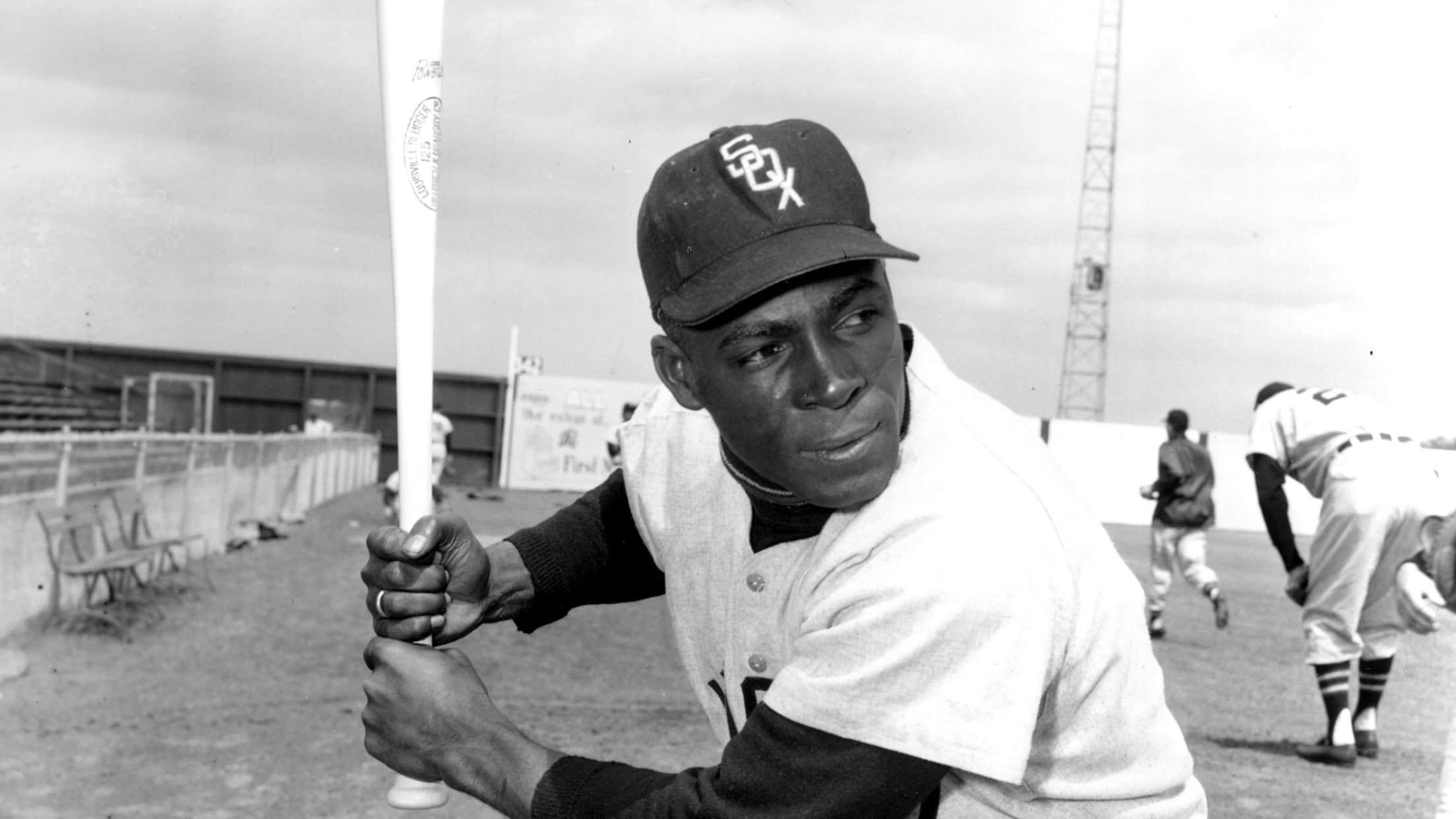

When I played baseball, I was neither white nor black and the white fans loved me. But after the game I was just another colored guy in town.

Vic Power

Even those on the Washington Senators, who employed nearly a quarter of Latino ballplayers prior to 1947, faced discrimination -- including their own teammates.

"Take the position of the Cubans and South American players on the Washington Senators," Eddie Gant wrote in the Chicago Defender on July 25, 1942. "They have been subjected to all sorts of abuses. Rival pitchers have been low enough to try 'beaning' them. In other instances, players on their own teams have refused to room with them, and in dining cars and other travel facilities discriminated against them."

"When I played baseball, I was neither white nor Black, and the white fans loved me," Vic Power once said, "but after the game I was just another colored guy in town."

The Hall of Fame

Perhaps the most crucial reason the game was held was to establish the Latin American Hall of Fame, with four players inducted on the day of the game.

There was Adolfo Luque, who won 194 games across a 20-year career with the Braves, Reds, Dodgers and Giants. He once led the league in losses with 23 in 1922 and then followed that up the next year by leading in wins with 27.

Hiram Bithorn played only four big league seasons that were interrupted by military service for World War II. He went 18-12 with a league-leading seven shutouts -- the most in a season by a Puerto Rican pitcher ever -- before entering the service in 1943.

And then there was Francisco "Pancho" Coimbre and Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda -- Orlando's father. While Luque and Bithorn played in the Major Leagues because of their lighter skin tone, allowing them to cross over the nebulous, ever-shifting color line, Coimbre and Cepeda could not.

Coimbre was a star in the Puerto Rican leagues before Alex Pompez convinced him to join the New York Cubans in the Negro Leagues. All he did was hit, finishing with a .332 average in four seasons.

And then there was Cepeda, a legend in Puerto Rico -- playing all over the field and astonishing fans at the plate. He resisted many offers to come and play ball in America because of the racism he would have to suffer.

Orlando Cepeda, now 83, still remembers the first time he ever saw his father play all those years ago. That day he manned second base during an 18-inning affair that saw the legendary Josh Gibson stay behind the plate for every frame.

"It was an amazing feeling having my father involved in that day. It really brought tears to my eyes," Cepeda said. "My dad isn't here today and through him and my mother, I played ball. So, having my dad involved that day, along with some great Latino players, I felt very proud to be the son of Perucho Cepeda."

There may have never been plans for a physical building, but the honor of induction was still significant. There were no Latino players in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and there wouldn't be one until after Clemente's death. If the league and voters weren't going to honor the Latin American greats, then the players had to do it themselves.

"So many great Latino players had played in the big leagues, and for some reason, they weren't recognized," Cepeda said. "And it stayed like that. Then you have an opportunity like this to really see who they are. In those days it was worse because so many great Latino players never played [in the Major Leagues]. They only played winter ball."

Part of the issue comes from the greater baseball public not understanding the struggles these players endured.

"How do we have a pioneering perennial All-Star player like Minnie Miñoso not in the National Baseball Hall of Fame?" Burgos asks. "Well, partly because we don't understand his journey, we don't understand how he's a man without a country after Cuba is cut off from the U.S. diplomatic relations, and he's still an All-Star. When Orlando Cepeda says he was our Jackie Robinson, this is not hyperbole. This is about how significant an accomplishment from a player who was pioneering and excellent."

This is an experience Oliva lived through, coming from Cuba himself. After the country was cut off from the U.S. he could not see his family or play in front of them.

"To be able to play in your hometown -- it’s the best thing you can do," Oliva said. "We used to have a beautiful winter baseball league. This is your home country, it’s where you want to play and visit and have people see you. My family never had a chance to see me. Or the friends I had in Cuba, they had no idea who Tony Oliva was."

So they're not just playing to find a voice. They're trying to build a voice.

Adrian Burgos

One month later, Felipe Alou published the essay, "Latin American Players Need a Bill of Rights," in Sport Magazine, highlighting his own encounters with racial prejudice and explaining how the needs of Latino ballplayers were still not being met. At the same time, the Giants owner, Horace Stoneham, had just visited the Caribbean and the Sporting News claimed that the "islands were more fertile producers of baseball talent than ever."

"So they're not just playing to find a voice," Burgos said. "They're trying to build a voice."

The Game

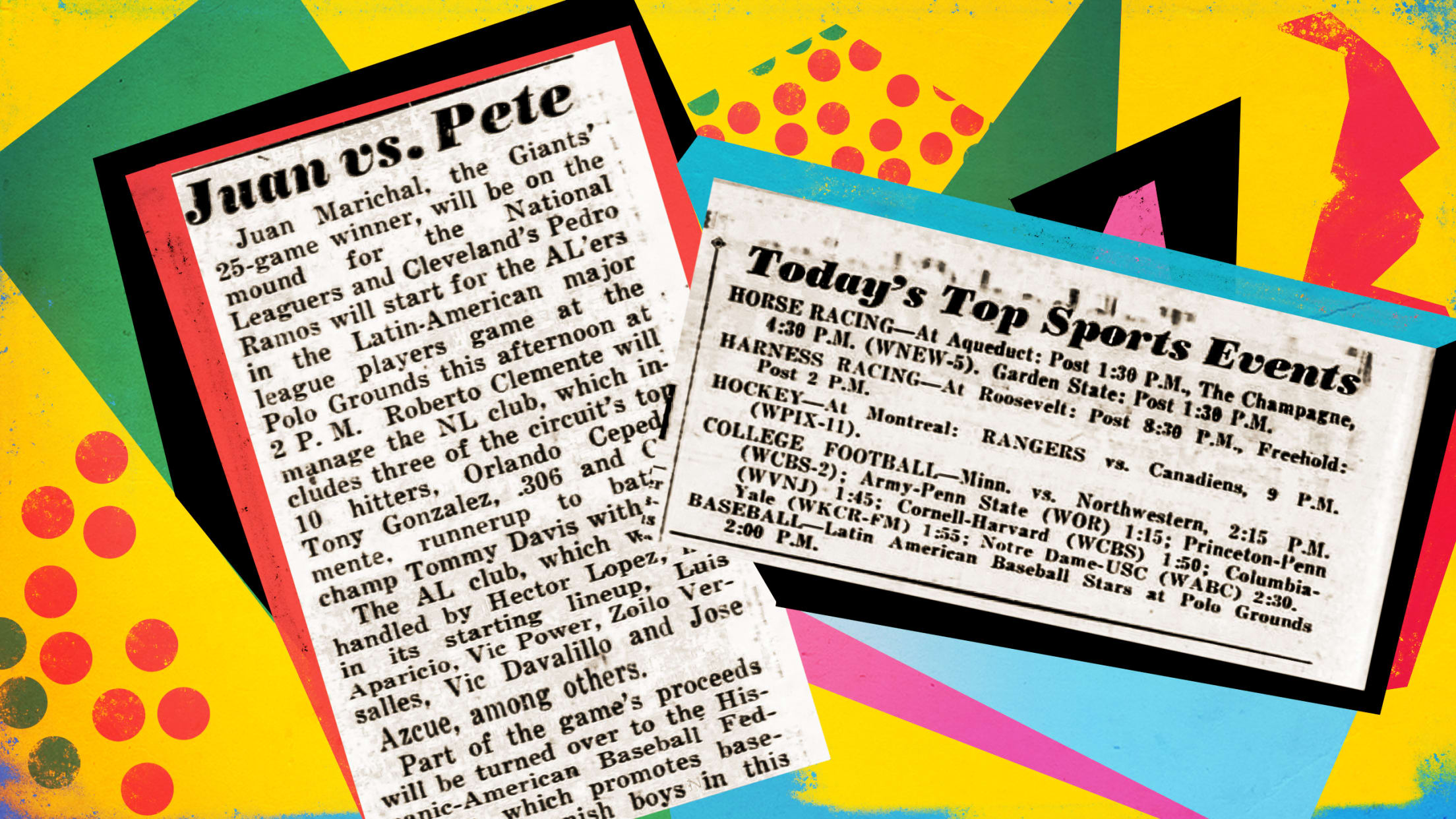

With all that history leading to this moment, there was still a game to be played featuring some of the game's greatest talents. Not that there weren't some complications. Some positions didn't have big league Latino ballplayers at the time, so the definition shifted a little.

Cuno Barragán -- the son of Mexican immigrants -- took over at catcher for the National League despite having only one at-bat that year for the Cubs. Joe Pignatano was also on the National League roster. He, however, was both not Latino -- he was an Italian-American from Brooklyn -- and he had only played in Triple-A that year. But, he was around and able to play. So, in he went.

It didn’t matter that it was for charity and that it wasn’t a ‘real’ All-Star game. When you put on your uniform, you played hard and you tried even harder to win.

Orlando Cepeda

Regardless, there was a lot of pride on the line.

“It was historic," Marichal said in 2013. "There was a lot of emotion among all the players, and you could tell the fans were excited about it, too.”

Cepeda added, “It didn’t matter that it was for charity and that it wasn’t a ‘real’ All-Star game. When you put on your uniform, you played hard and you tried even harder to win. And that’s what everybody did in that game.”

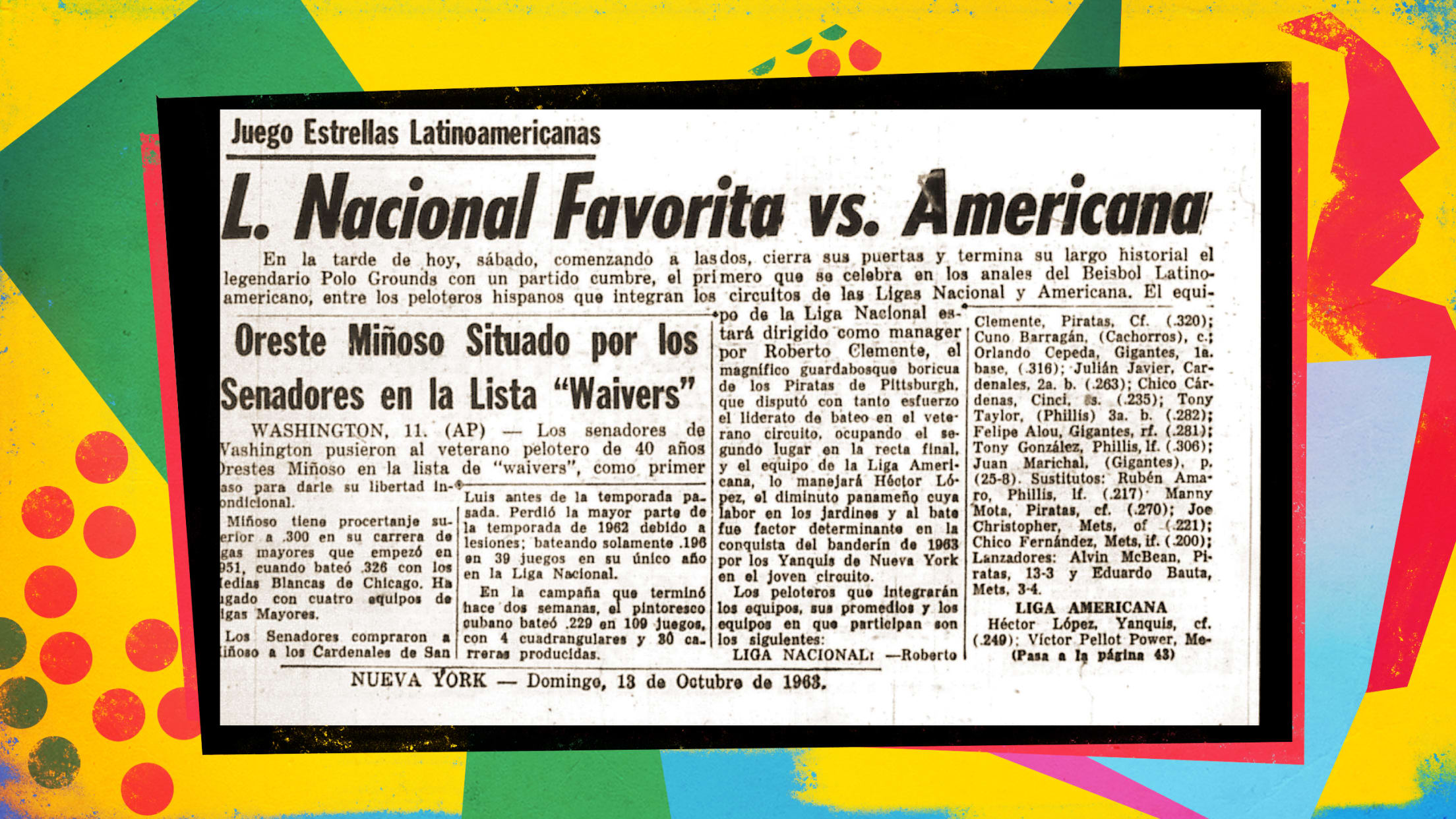

El Diario La Prensa, the most prominent Spanish language newspaper at the time, thought the NL was the obvious favorite. With Marichal on the mound, the National League had the clear edge in pitching, while the lineup featuring Tony González, Clemente, and Alou had "among the six best players in the National League." Most predictions are doomed to fail, but this one proved true.

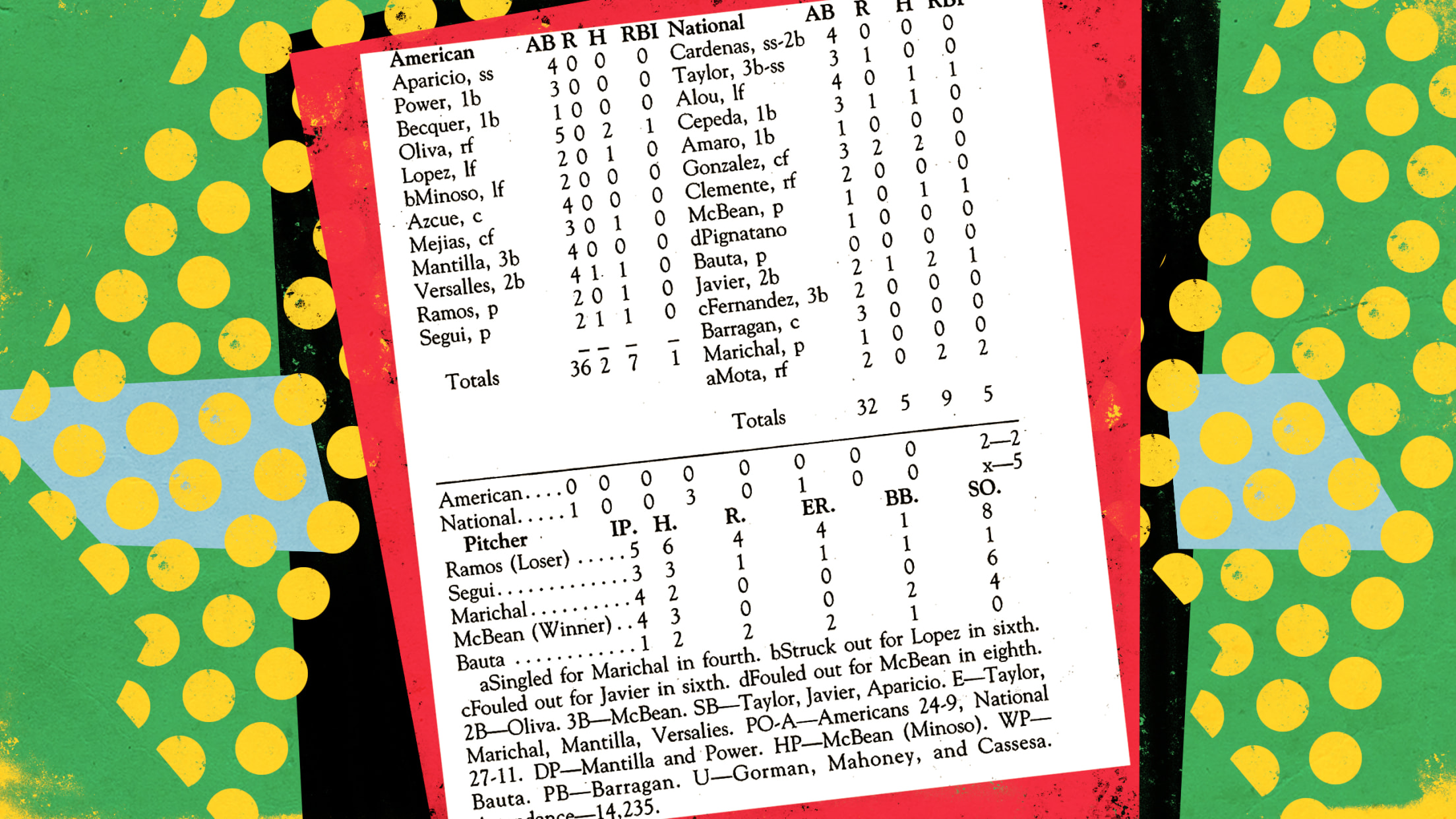

Marichal pitched four shutout innings and struck out six along the way. Al McBean then took over and pitched four more shutout frames to earn the win. He nearly walked away with an inside-the-park homer, too. In the sixth inning, McBean blasted a ball to left field and could have happily taken his triple, but he instead tried for home. That didn't work out so well.

“There was a Listerine sign in left field [right of the 422-foot marker],” McBean told SABR, “and that’s where I hit the ball. It was a lot of fun.”

Leading 5-0 going into the top of the ninth, the American League made a last effort to come back. They scored two runs off the Mets' Eduardo Bauta, with Versailles and pitcher Diego Segui coming around. Oliva was credited with one of the RBIs and he finished the day 2-for-5 with a double and the RBI. But it wasn't enough -- the NL won, 5-2.

After the game, the players lined up to receive their checks for the appearance. The amount they earned for playing? $175.

"After me, Roberto Clemente and Vic Power got paid, we got on line again," Cepeda told the Daily News with a laugh.

Today

The next day, the players headed to Miami for another exhibition to raise money for Cuban Refugee Relief. This time, the Twins' Camilo Pascual took the mound for the American League.

"This is again what's fascinating because Clemente and all these other guys are actually envisioning a world where they can transfer what they're able to do as Major Leaguers to have impact beyond themselves," Burgos said. "And this is what really becomes Clemente's mission. He lives that mission. That All-Star game becomes like one of these early efforts towards trying to have impact."

Unfortunately, what was meant to be an annual event was never pulled off again. The schedules couldn't align for the players and a suitable venue could not be arranged in the days after the season ended. But it was a watershed moment. Latinos eclipsed 10 percent of the league in 1965 and eight Latino players were invited to the Major League All-Star Game that summer.

There was still so long to go. Clemente was referred to as "Bob" on his baseball cards and it took until 1969 for a Latino manager to be hired at the start of a season when Preston Gómez took over the expansion Padres.

These days, roughly 30 percent of big leaguers are Latino. There are heritage nights held by almost every team, and there has been a concerted effort to include their voices, their input, and put their impact on the game front and center.

The teams have gotten better at how they treat Latino players, as well. Oliva admitted that there was plenty to be anxious about as you made the transition to a new country and a professional career with little help from the team. You simply had a few Spanish-speaking teammates to assist you. But now, teams like the Twins offer much more guidance to their young players.

"We have a beautiful system in Fort Myers, Florida where we can put up 150 players there," Oliva said. "There’s a complex and you have breakfast, lunch and dinner. There’s a school there with people teaching you the language. So you don’t have to worry about anything, it’s very convenient."

There is still room to grow and Cepeda would love for this All-Star Game to return, for the Latino baseball community to come together once again and help learn from each other. That idea of a community, which was on display at this All-Star Game, is still at the center.

"I would love to have that game come back for the fans and for us," Cepeda said. "We'd have a chance to spend some time together. So many great Latino players [these days that are] like Pedro Martinez, Juan Marichal, Felipe Alou -- those great Latino ballplayers, you never saw them. If you played the game, we’d have a great opportunity to spend some time with them, and they would also like to spend some time with us."