It is one of the most entertaining developments of the first half of the season that while Cleveland’s Steven Kwan carried a .389 batting average into Tuesday, giving rise to hopes that he’ll be the first .400 hitter in more than 80 years, this really isn't a story about batting average at all. It's not about making contact, going the other way or finding holes in the defense.

It’s about hitting for power. It's about getting off the ground. It’s about one of the lightest-hitting bats in the league adding slug. On purpose, even. (All stats below are through Monday.)

Kwan really couldn’t have been clearer about it. In February, he appeared on the “Just Baseball” podcast and outlined his plan specifically, saying, “We are focusing on bat speed and exit velo. We are recalibrating to tap into the power side.” His manager, Stephen Vogt, echoed that just this week, telling MLB.com’s Mandy Bell that Kwan “worked on [hitting the ball harder] … he made a conscious effort to work on impacting the ball just like a lot of our guys.”

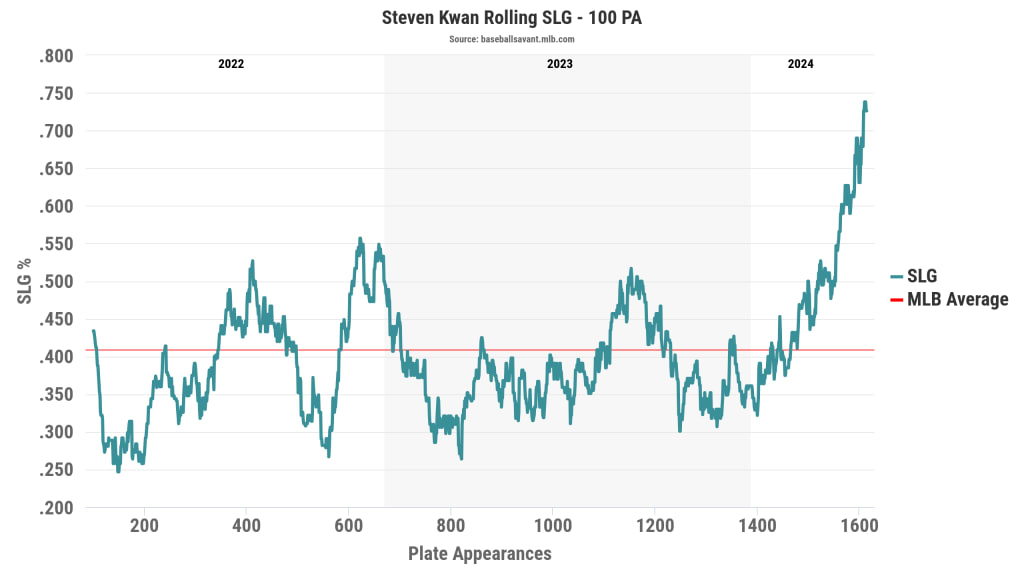

The plan was indisputable. There’s no both-sides-ing this, because he openly explained it. Even if it came at the expense of swing-and-miss, Kwan was determined to add power to his game. If you were to look only at this amazing graph that shows his slugging going up-up-up …

… or realize that only Aaron Judge, Royce Lewis and Bryce Harper have a higher slugging percentage than Kwan since May 30, the day he returned from a hamstring injury, you’d say it worked wonderfully. “Player works hard at a skill, then improves that skill” is a fantastic narrative, and it’s not exactly flukish: He rates in the 91st percentile in Statcast’s Expected wOBA, up from the 36th percentile last year, and that accounts for contact quality as well as strikeouts and walks

… except …

Except there are more than a few unanswered questions here. Kwan’s hard-hit rate, which was the weakest of any qualified hitter in 2023, is still in the bottom five in 2024. Despite being willing to trade strikeouts for slugging, his whiff rate isn’t up – it’s actually down, by half. And, while we don’t have 2023 bat speed data to compare to, when he gets in a few more swings and qualifies for the 2024 leaderboards, he will do so at or near the very bottom of the list.

If Kwan’s goal was to add power, he’s succeeded tremendously – no one has added more slug than he has. Yet if his goal was to swing faster and hit harder, then there’s not a whole lot here to show that he’s done so. You might be able to luck your way into a high batting average, just based on the ball finding dirt or not. (And he has, a little, with a .400 batting average on balls in play.) It doesn’t really work that way for slugging.

So: Which is it?

He is, for one thing, acting like a power hitter. Imagine if Luis Arraez, generally considered his closest offensive comp, went off and did this, like Kwan is:

- Kwan is hitting way fewer grounders. His ground-ball rate has dropped from 47% to 36%, which is the fourth-largest drop in the Majors.

- Kwan is pulling the ball in the air way more. Last year, when he hit the ball in the air, he pulled it 18% of the time. This year, he’s doubled that, doing so 36% of the time. Put another way, he’s hit nearly as many pulled airballs this year (39) as he did the entirety of last year (50).

This is not the way a singles hitter approaches things, but if you’re trying to add power, and meaningfully adding hard-hit rate is almost impossible when you start out this low – as an award-nominated FanGraphs piece investigated in 2022 – this is pretty much the only way to do it. He’s not even hitting those airballs harder or much farther. He’s just doing it more. (Nor is there anything notable about any changes to Progressive Field, at least not for Kwan, who shows no home/road split.)

All of which makes a lot of sense when you look at Kwan’s career extra-base hit chart. Sure, he can slap a ball down the line or into the gap and use his speed to make it a double, but if we’re talking about home runs, there’s only one place they can go: right field.

It’s not that “hit the ball in the air to your pull side for some power” is some earth-shattering new idea. Isaac Paredes has made a career of it recently, and it’s not hard to go back in time to find examples such as Didi Gregorius or Brian Dozier. It’s just that A) It’s a lot easier said than done, and B) It doesn’t usually come from this profile of a hitter, the slap-hitting, speedy batting average/contact king. If anything, it just says more kind things about his elite bat control that he’s able to just say he’s going to do this, and then do it.

“He doesn’t try to hit for power, but when it’s in his damage zone, he’s getting the barrel to it,” said Vogt.

That concept, for Kwan, is extremely easy to show. Where’s his damage zone? Inside, and middle-low/middle-middle, where he can pull it out to right field. Where is he swinging more than ever? Inside and middle-low/middle-middle, but only when he’s ahead in the count.

But there’s something else happening here, too. Look at when Kwan is finding power.

He is, entertainingly, “not clutch.”

- High leverage // .290 BA, .368 SLG

- Medium leverage // .380 BA, .600 SLG

- Low leverage // .462 BA, .646 SLG

Let's be clear on what that means: No one thinks this is showing you that Kwan "can't handle the big moment," or however you might define being clutch.

Instead, is it more that he is abandoning his new approach when it “matters” more? Kwan’s ground-ball rate is 32% in both low- and medium-leverage moments, but skyrockets up to 59% in the biggest spots – and his opposite-field rate jumps from 30% to 50%. It’s not hard to think that in certain spots, a soft opposite-field single to get the run home is more important than anything. It might also be making him a less effective hitter, too.

Kwan is also absolutely pounding starting pitchers foolish enough to face him for the third time in a game.

- Starters, first time // .313 BA, .438 SLG

- Starters, second time // .300 BA, .425 SLG

- Starters, third time // .606 BA, 1.061 SLG

This, like it is for so many other hitters, might be about the familiarity gained by seeing the pitcher’s repertoire repeatedly. (It might also be a good idea for opposing managers to not actually continue to do this.) But it’s also about Kwan, who decreases his ground-ball rate from 39% to 25% after the second time through, and increases his pull rate from 35% to 43%.

Those aren’t coincidences, not at all. It’s a strategy. It’s trying to hit for extra bases.

Maybe Kwan didn’t end up meaningfully increasing his hard-hit rate or his bat speed, because there wasn’t really ever a universe where a player listed at 5-foot-9 and 170 pounds was going to hit lasers like Judge or Shohei Ohtani, and he won’t hit .400, either. But the offseason work still seems like it paid off, because this new version of Kwan might be a little less prone to the ups and downs that light hitters like Jeff McNeil and David Fletcher have run into, also, because for anyone who isn’t Arraez, it’s really, really difficult to count on the good luck of batted balls finding grass for years on end.

Steven Kwan, power hitter. It’s not what you expected. It’s not an accident, either.

Mike Petriello is a stats analyst for MLB.com, focusing on Statcast and Baseball Savant, and is also a contributor to MLB Network.