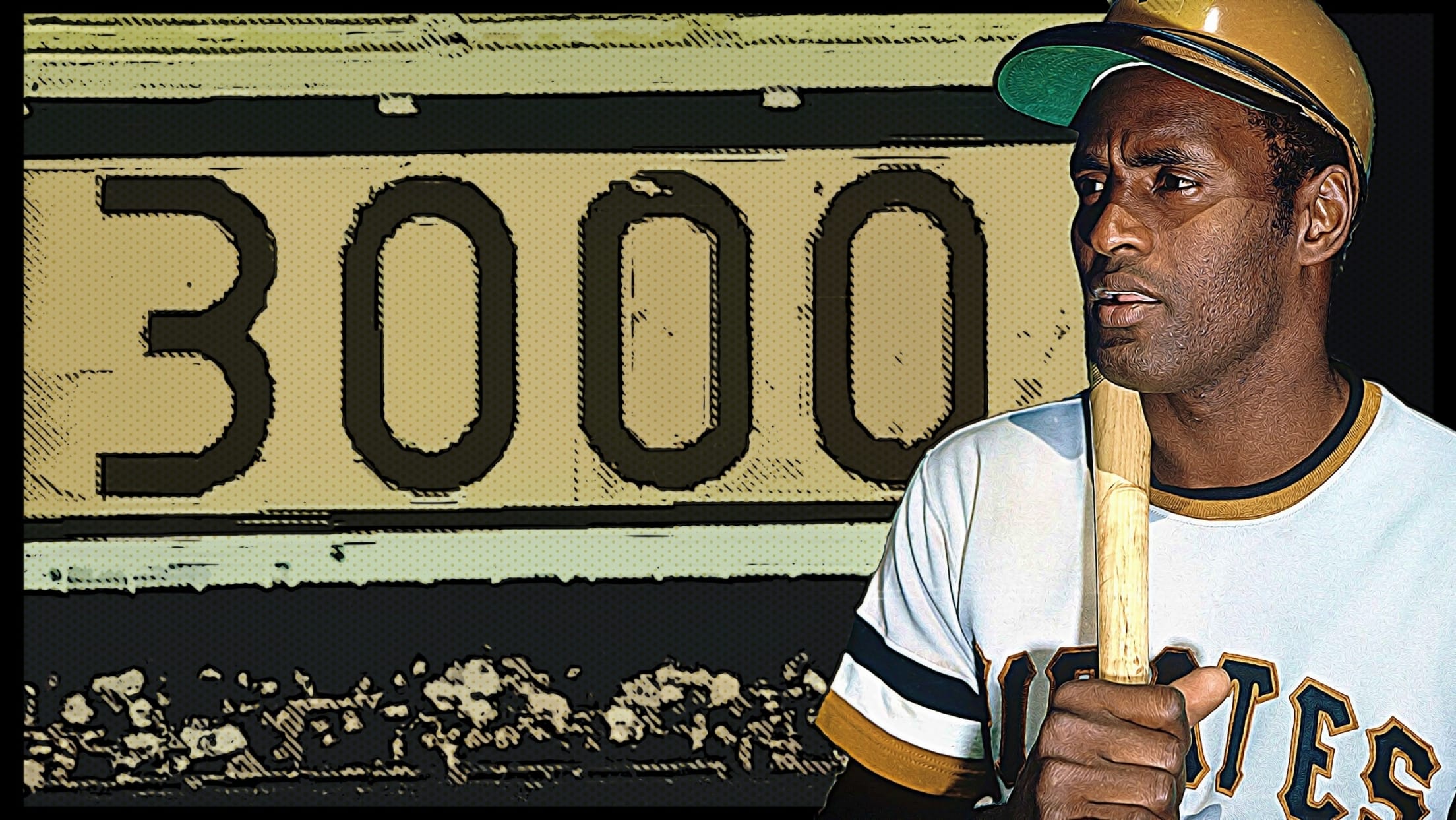

Roberto Clemente: Forever 3,000

No one knew it at the time, but the great Roberto Clemente’s quest to become just the 11th player in history to reach 3,000 career hits was also a race against the clock.

Tragically, Clemente had just a few short months left to live when he entered the 1972 season 118 hits shy of becoming the first Latino player to reach the hallowed number -- which at that time meant an automatic ticket to the Hall of Fame.

The Pirates legend died on Dec. 31, 1972, when the plane he was traveling on with humanitarian aid supplies for earthquake-stricken Nicaragua crashed after taking off from his native Puerto Rico.

Although Clemente had already spent 18 seasons with Pittsburgh and was 38 years old at the time of his death, he appeared to be in outstanding physical shape. In fact, just a year earlier he had won the World Series MVP award as the Pirates edged the Orioles in a seven-game series on their way to the franchise’s fourth title.

However, he had a strong sense that he must reach the milestone during the 1972 season. According to longtime baseball executive Luis Rodríguez Mayoral in an article for La Vida Baseball, Clemente told him that spring, “My 3,000th, I have to get it this season.”

* * *

Unfortunately, it was difficult for the veteran to stay on the field that year, which made reaching the 3,000 mark less of a sure thing than most would have expected when the season began. After all, he had amassed at least 118 hits in every season of his career except 1957, and even topped 200 hits four times.

But despite his statuesque appearance, Clemente had a long history of spinal problems. And he had even dealt with a bout of malaria before the ’65 season.

“He looked like a specimen,” said Pirates pitcher Steve Blass, Clemente’s teammate for eight seasons. “He looked like he was 25, on top of looking like he could be a movie star. But there were physical issues with him.”

* * *

Those physical ailments, more than pitchers around the National League, would be the biggest reason Clemente’s chase for 3,000 would ultimately go down to the wire during a season in which he slashed a robust .312/.356/.479. He appeared in just 102 games -- the fewest of his career -- although a players’ strike that delayed the start of the season to mid-April contributed to that total, as well.

Clemente was hitless in his first two contests before picking up multi-hit games in three of his next five. He finished April with 12 hits in 47 at-bats (.255). A scorching May during which he batted .365 with 35 base knocks positioned Clemente just 71 hits shy of 3,000 with four months left to play.

In June through August, though, those health issues limited the All-Star to just 39 games, and Clemente stood 30 knocks shy as September rolled around.

Manny Sanguillen, a three-time All-Star catcher from Panama who went from idolizing Clemente to being his closest friend on the Pirates, recalled how much missing games bothered the legendary right fielder.

“One night we were in Atlanta in ’71, and it was really hot, over 90 degrees,” Sanguillen recalled. “[Clemente] said to me, ‘I can’t get out of the lineup because I want 3,000 hits. I have to be the first Latino to get to 3,000 hits.’

“I ordered fruits and water from room service, and stayed with him until 3 o’clock in the morning. People don’t know what he went through. He also had problems with a tendon in his back. His body was giving out.”

* * *

The great Clemente would need to somehow remain healthy enough to put together a strong final push. Unsurprisingly for a player who was at his best when the pressure was high -- he did, after all, hit safely in all 14 World Series games he played in -- Clemente was up to the task.

From Sept. 2-7, he picked up seven knocks and hit safely in five straight games. He had three hits in each game against the Cubs at Wrigley Field on Sept. 12-13, including his final career home run off fellow future Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins on Sept. 13.

Clemente followed up his final career homer with another six hits over the next three games, giving him 2,990 with two weeks remaining. Suddenly, the milestone was once again very much in play.

While anticipation for the magical moment was beginning to build in the Pirates’ clubhouse and around Pittsburgh, there wasn’t nearly as much hype around Clemente’s chase as fans would expect today.

“It was well-noted, but nothing like it would have been like in Chicago, New York or L.A.,” said Blass.

“In that time,” added Sanguillen, “we Latinos didn’t get a lot of press.”

After three more multi-hit outings in his next eight games, Clemente was just two hits shy with five games left on the Pirates’ schedule. He collected No. 2,999 -- a leadoff single off the Phillies’ Steve Carlton, another future Hall of Famer -- in the Bucs’ last road game of the season.

* * *

It was back home in Pittsburgh where Clemente would make his final charge at immortality. He had four games left.

“To get 3,000 hits means you’ve got to play a lot,” Clemente told reporters. “To me, it means more. I know how I am and what I’ve been through. I don’t want to get 3,000 hits to pound my chest and holler, ‘Hey, I got it!’

“What it means is I didn’t fail with the ability I had. I’ve seen lots of players come and leave. Some failed because they didn’t have the ability. And some failed because they didn’t have the desire.”

My 3,000th, I have to get it this season.

Roberto Clemente, Spring Training, 1972

In his first plate appearance of the final homestand, Clemente was briefly credited with an infield single off the Mets’ Tom Seaver, yet another future Hall of Famer. But the official scorer then ruled the play an error by second baseman Ken Boswell.

“Well, maybe it will be tomorrow,” Clemente told Mayoral. “But I have not been sleeping well lately.”

Clemente wouldn’t leave any more room for suspense. He was ready for the chase to end. The next night, following a first-inning strikeout, Clemente laced a double to the gap against Jon Matlack, that year’s eventual Rookie of the Year, to begin the fourth.

“The script that you couldn’t write any better was a ringing double to left-center field,” said Blass. “Not a dribbler. Not a pop fly down the right-field line. And against a quality pitcher like Jon Matlack.

“That pose at second base. I’ll never forget it.”

The 13,117 fans on hand at Three Rivers Stadium gave Clemente a standing ovation.

“I felt so uncomfortable when all those people applauded me,” Clemente told Mayoral.

Thanks to a torrid September in which he batted .333 and hit safely 30 times, the 15-time All-Star became the first Latino to reach 3,000 hits. His teammates were ecstatic.

“I was one of the happiest people in the world,” said Sanguillen. “All the Latinos were happy. Now you see how many there are in baseball.”

* * *

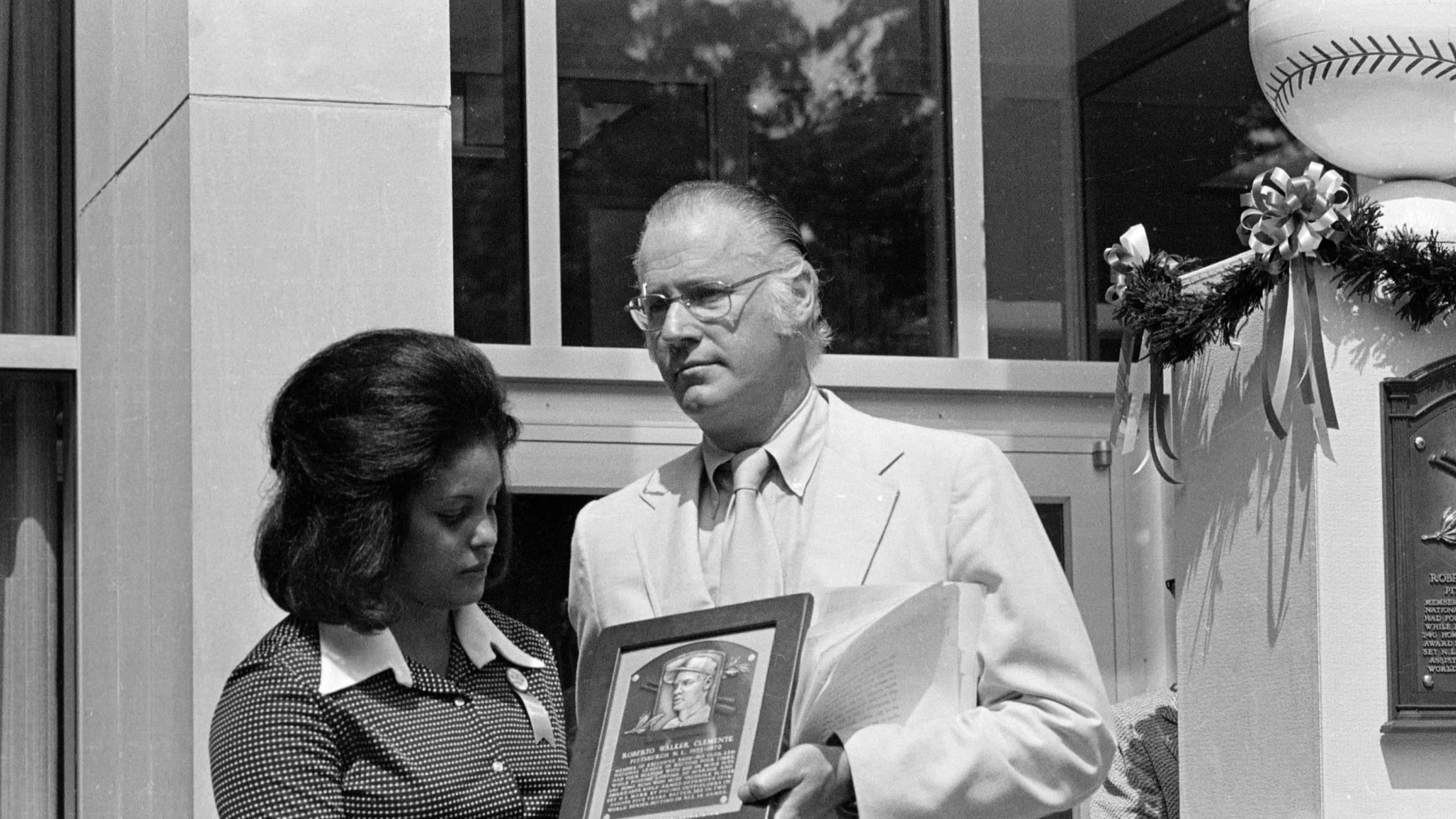

Clemente would also become the first Latino enshrined in the Hall of Fame the next summer, when the normal five-year waiting period was waived after his tragic death.

A man whose legendary humanitarianism sometimes overshadows just how great of a ballplayer he was beat the clock that no one knew was ticking, and is forever stuck on 3,000 hits -- a magical number that’s become nearly as synonymous with him as the No. 21 he wore.

The clock, of course, was no match for an immortal like Clemente, whose legacy lives on in so many ways, 50 years later from the Clemente Bridge outside PNC Park to the prestigious award that bears his name and is bestowed annually to the player who best represents what all big leaguers aspire to be on and off the field.

Roberto Clemente is forever young, forever proud, forever remembered by those he’ll inspire for generations to come.

Ed Eagle is an editorial producer for MLB.com. He covered the Pirates for MLB.com from 2001-07.