Rickwood Field road trip -- Part II

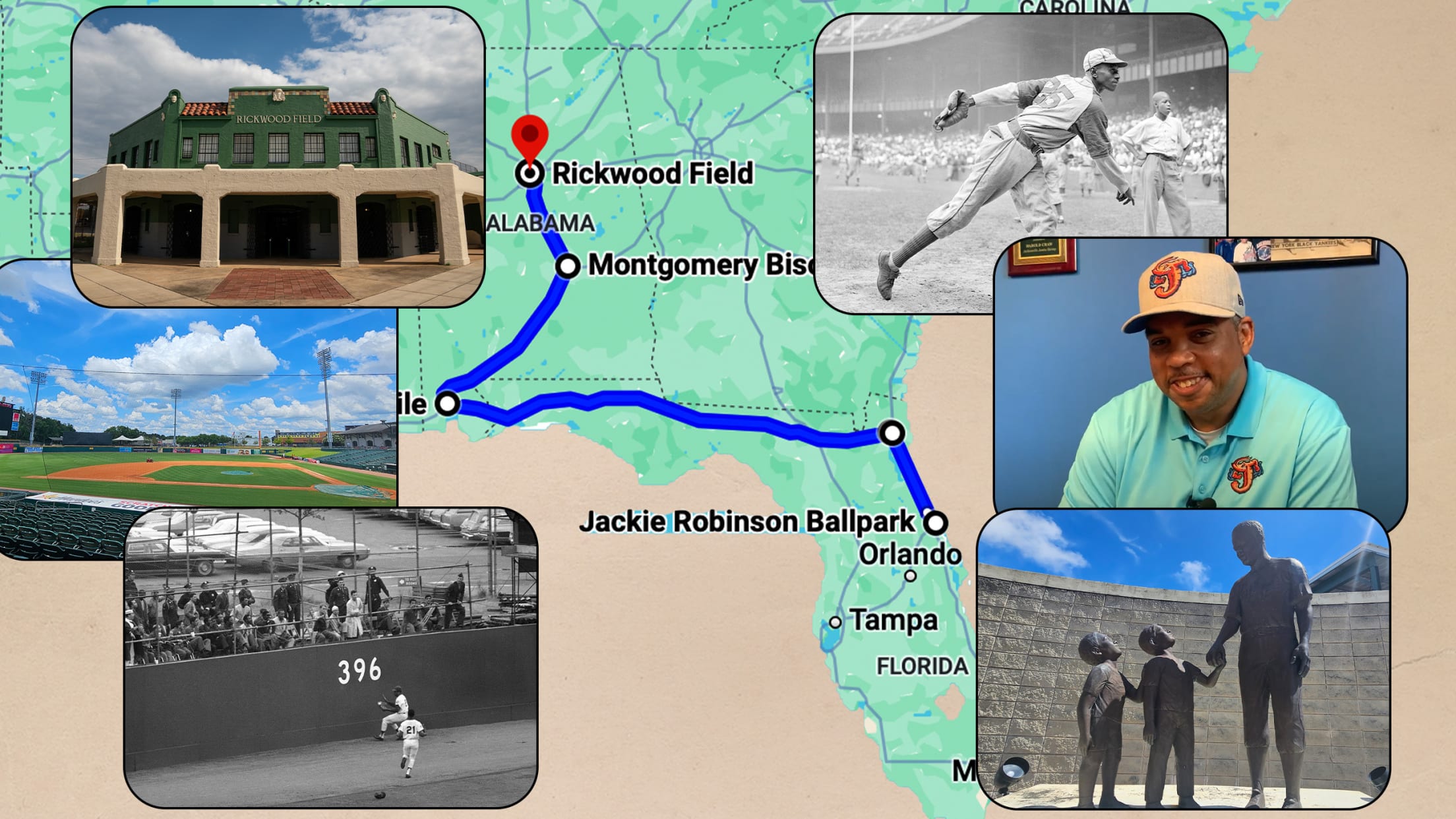

Birmingham’s Rickwood Field – the oldest professional baseball stadium in America, standing since 1910, and the former home of the Negro American League’s Birmingham Black Barons – hosted Minor League Baseball and Major League Baseball games this week, and on the way to the hallowed ground, MLB Pipeline took a road trip through Florida and Alabama in search of more stories that tell the history of Black baseball in the South. Part I of that trip, covering stops in Daytona Beach and Jacksonville, is available to read here. Part III, covering multiple stops in Birmingham, is here.

MOBILE

“Nobody ever talks about that!”

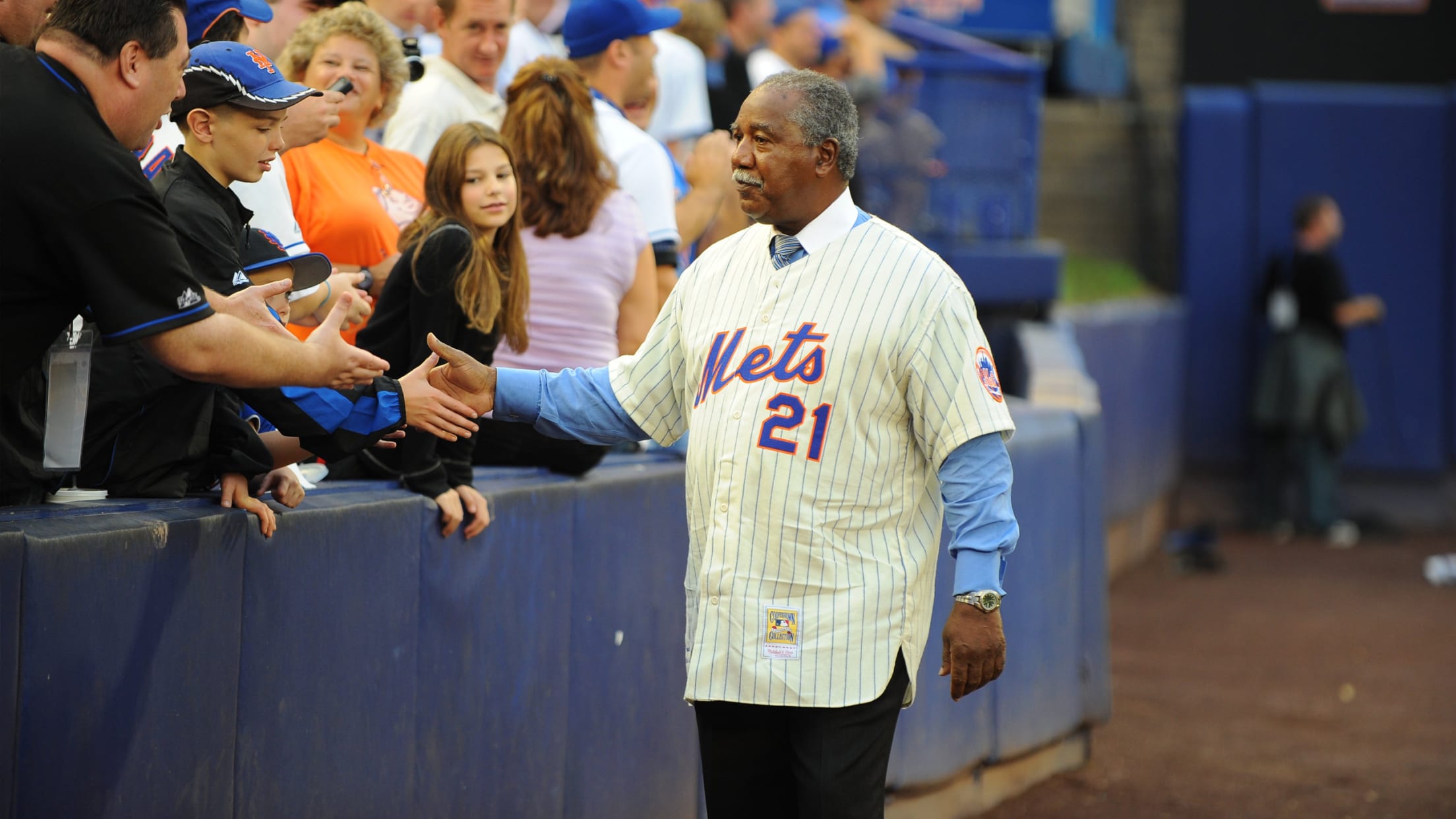

We’ve driven five hours west of Jacksonville, crossed the border into Alabama, crashed the night at another LaQuinta Inn in Daphne and headed to the Ruby Slipper for Monday breakfast in Mobile, where we’re met by 13-year Major Leaguer and 1969 World Series champion Cleon Jones and his wife Angela who still live in their hometown city by the Gulf.

We’re not talking about the Miracle Mets in this specific case – but that comes up plenty between bites of eggs, grits and French toast – but rather, Mobile’s direct influence on the 1969 National League as a whole.

Three Mobile natives earned starting spots in that year’s NL All-Star lineup at RFK Stadium in Washington – Hank Aaron batted third and started in right field, Willie McCovey batted cleanup and started at first base and Jones (in his only Midsummer Classic appearance) batted seventh and started in left. Zoom forward a few months, and four players from the area finished among the top seven in NL MVP voting – McCovey in first, Aaron in third, Tommie Agee in sixth and Jones in seventh.

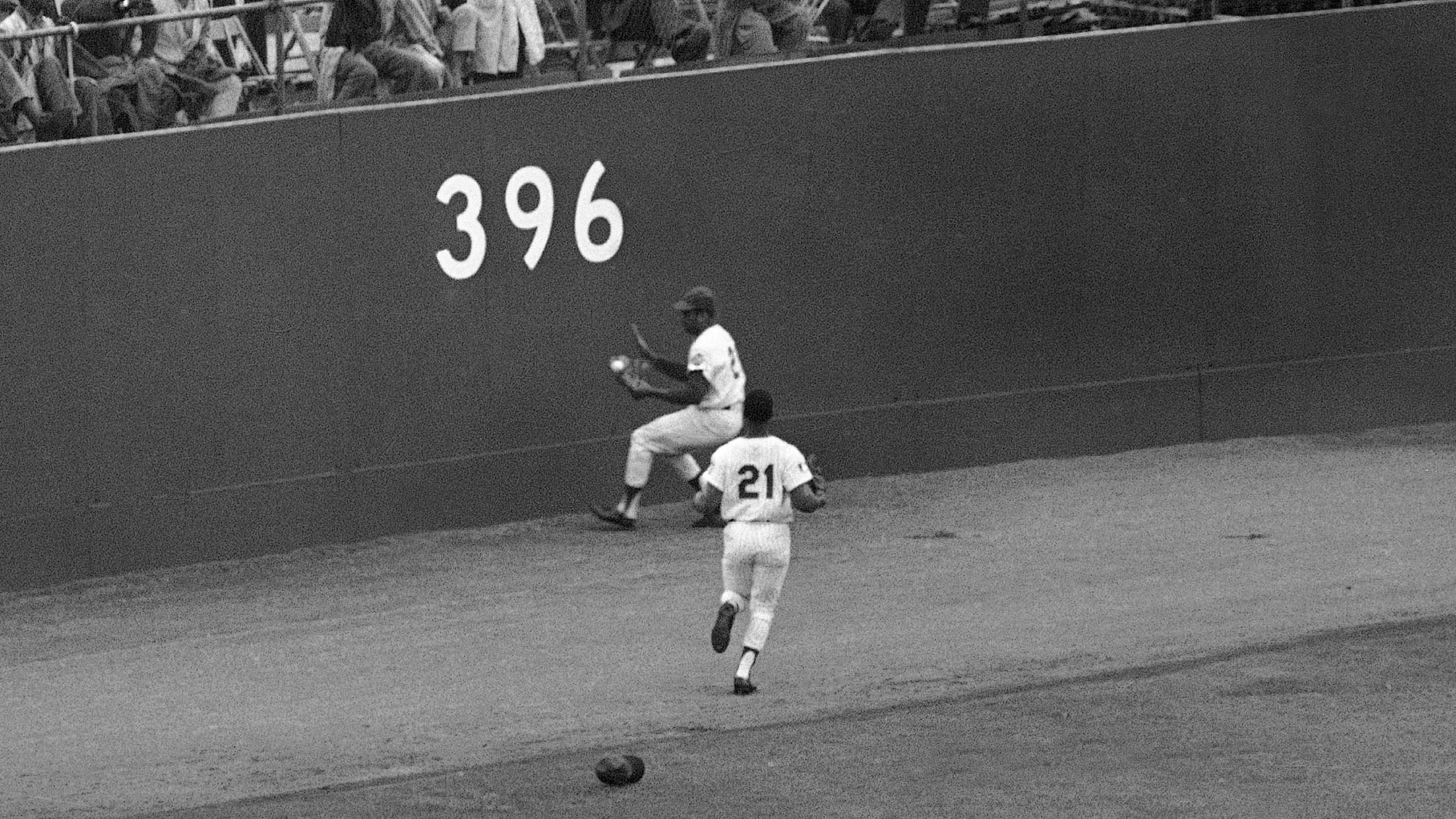

Much was made at the time about the partnership of Agee and Jones – two former baseball, basketball, football and track teammates at Mobile County Training School – in the New York outfield (as seen below), and that kicked into another gear when the pair shared a roster with fellow Mobilian Amos Otis. Jones, Agee and Otis shared the outfield grass as a trio four times for the Mets in ’69.

Jones notes that Aaron, whose brother Tommie also saw time in the bigs and whose childhood home was recently relocated to its original neighborhood in Toulminville, used to say “there was something in the water” around Mobile that led to the NL dominance in this period. But the origin might also have something to do with another Mobile native, Satchel Paige.

Every city needs a good local legend, but they don’t come much more legendary than the fireballing right-hander. Jones recalled hearing stories of Paige telling his infielders to sit down while he mowed down opposing hitters, and realizing some of that happened right around the corner in his neighborhood in Plateau was a big inspiration.

“Satchel was always the talk of the town,” he said. “They’d always talk about what Satch did – what he did at this park, what he did at that park, what he did here.”

Those legends became real for Jones and other Black ballplayers when Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers and debuted in the National League in 1947. Jones, who was only five years old at the time, recalls gathering around the radio with his grandparents to tune into as many Brooklyn games as they could.

“We would sit around that like we were watching TV,” Jones said. “We would hear Dizzy Dean or someone like that say, ‘That one was high and tight.’ My great-grandmother would say to the radio, ‘Look out, Jackie, they’re throwing at you.’”

In the middle of the 20th century, having legends live on through neighborhood tales or over the airwaves made baseball an aspirational sport for Mobilians like Jones, and the relative low cost of the game allowed for a feedback loop. The higher the interest, the better the players, the higher the interest, and so on. That helped Jones set aside his football days at Alabama A&M when the Mets came to sign him as a ballplayer in their first year of existence in 1962.

Jones didn’t own his first personal glove until he was 13 – and he kept that same mitt until making the Majors at 21 – because he borrowed from friends, including ones who were right-handed while he was a left-handed thrower. He even learned to hit righty at a local park in order to avoid pulling balls into water beyond right field as a lefty.

These were low-cost, community-driven ways to get local kids involved in baseball. The result: five Mobile natives currently sit in the Hall of Fame – Aaron, McCovey, Paige, Ozzie Smith and Billy Williams.

Jones is heavily involved in a downtown Mobile project called Heroes Plaza aimed to honor those Cooperstown greats back home. Ground was broken on the site last November, and nine-foot-tall statues of all five are standing by to be in put in place when work is complete. The opening ceremony is scheduled for next year, and Jones is helpful that Mobile, which has seen declining baseball interest since the mid-1980s, could lead to a local resurgence in the national pastime.

“It’s not always been about us, but the pride we should have as Mobilians,” Jones said. “Most Mobilians are not familiar with all the things we’ve talked about. But when I go around the country, I’m asked the same question all the time. Why were there so many great Mobile ballplayers? It wasn’t anything about the water. It was about the ability to play and compete with so many great athletes.”

MONTGOMERY

It takes about 2 hours, 30 minutes to drive north from Mobile to Montgomery, Alabama’s state capital and the home of Double-A Montgomery. The club’s home ballpark Riverwalk Stadium sits near the banks of the Alabama River and less than half a mile from the Rosa Parks bus stop, highlighting that American history is never far away from baseball.

The Biscuits were the visitors in Tuesday’s MiLB at Rickwood game, eventually winning 6-5 over host Birmingham, and donned Gray Sox uniforms to mark the occasion in celebration of a local team that moved between the Negro Southern League, industrial leagues and other local circuits in the 1920s and ‘30s. The club played at Southside Park, which now sits on the modern-day campus of HBCU Alabama State.

A Birmingham-Montgomery matchup shouldn’t have come as a shock to anyone who knows Rickwood history. The Birmingham Barons and Montgomery Climbers played in Rickwood’s first game on Aug. 18, 1910 in front of an estimated crowd of 10,000. More than a century later, Birmingham and Montgomery – wearing old-school Barons and Climbers outfits – competed in the Rickwood Classic on May 29, 2019 in the last affiliated game in the historic park before this week.

The modern Biscuits front office was already making plans to continue to tap into the area’s history with Negro League nights in 2024, when word came down in June last year that they would be on the schedule for the Minor Leagues’ return to Rickwood. Moving the Gray Sox identity that was already in motion to the Birmingham ballpark only made sense. But the Biscuits have extended the Gray Sox look through the week with jersey giveaways (with a more modern feel) on Friday and Sunday as they continue to tap into and recreate the more positive attributes of Montgomery baseball history.

“Digging into some of the newspaper articles we found, obviously this was Montgomery during segregation, but there were some quotes where fans said going to a baseball game was like going to neighbor’s house or going to a friend’s house,” said Biscuits general manager Michael Murphy. “It was a place where they could let loose and be themselves. The baseball park was where somebody felt really comfortable, and that was really powerful to read.”

That neighborhood feel and local pride should sound familiar to anyone who’s ever been to a Minor League park, and bringing the Gray Sox energy and look to Riverwalk Stadium (and possibly beyond) isn’t something that will stop in Montgomery in 2024.

“It’s not like we’re going to wear this once and then auction it off,” Murphy said. “We’re keeping these uniforms for as long as we can.”