The Red Sox, you might have heard, have largely stopped throwing fastballs, living at the cutting edge of the modern pitching philosophy that realizes that the outcomes on fastballs are the worst of any pitch, and that no, you don’t really have to “establish your fastball.” Early this season, this was a hot topic, with stories about it in multiple local and national outlets, some before they even played their first home game.

Now, over 40% of the way through the season, it’s not a fluke. They’re still not throwing them. And Boston, which finished 21st in the Majors in ERA last year (4.52), ranked fifth this year (3.42), entering Thursday night's game against the Phillies, with a weekend series against the mighty Yankees lineup looming.

But the thing about not throwing fastballs? That’s only partially true. It’s not simply that the Red Sox and new pitching coach Andrew Bailey have mashed the “stop throwing fastballs” button, in defiance of 150 years of established pitching history. You can still throw fastballs on this Boston team. They just have to be good ones.

Another way of saying that: It’s not that they’ve stopped throwing fastballs. They’ve just stopped throwing the bad ones. When you say it like that, it actually sounds kind of simple.

It is, as you’ll see, not.

All numbers below are through Wednesday's games.

To start with: Yes, they really are throwing fewer fastballs (defined here as four-seam and sinkers) than any team in the pitch-tracking era, dating back to 2008. We don’t have reliable data before that, other than to say that it’s extremely hard to believe anyone in baseball history earlier than that was really throwing fewer fastballs, so it’s reasonable to think this might be the least fastballing team ever.

Lowest fastball rate, 2008-pres. (2020 excluded)

- 35% – 2024 Red Sox

- 41% – 2024 Rays/Twins, 2022 Rays,

- 43% – 2023 Giants/Angels/Reds/Guardians, 2021 Rays

That’s down from 48% last season, which leads us to the next question: Is it about a change in pitchers? Or a change in philosophy?

There’s a relatively easy way to answer that question, which is to split the 40 pitchers who have appeared for the 2023-24 Red Sox pitchers into three groups – those who pitched for Boston only last year, those who pitched only this year, and those who pitched for Boston in both seasons. (We’re including Joe Jacques in the “only 2023” group, as he appeared 23 times last season but just once this year before being lost on waivers to Arizona.)

- Pitched for Red Sox in 2023 only:

48% fastball usage in 2023.

- Pitched for Red Sox in 2024 only:

33% fastball usage in 2024.

That's a good start: Last year’s fastball-first arms like Kaleb Ort, Mauricio Llovera and Jacques have largely moved on, replaced by newcomers like Chase Anderson, Cooper Criswell and Justin Slaten – who were either not heavy fastballers to begin with or cut that usage upon joining the team. What about the pitchers who stuck around for both seasons?

- Pitched for Red Sox in 2023 AND 2024:

48% fastball usage in 2023 and 36% fastball usage in 2024.

Meanwhile, returnees like Bryan Bello and Garrett Whitlock have markedly cut their fastball rates.

So it's both, then: They've swapped out fastballers for not-fastballers, and made changes to those who stayed. Not, of course, that it’s a one-size-fits all thing. Pitchers like Joely Rodríguez, Brennan Bernardino, and Nick Pivetta haven’t changed much at all, at least fastball-wise. There’s a good reason for that.

So where have the missing fastballs gone? Let’s find out.

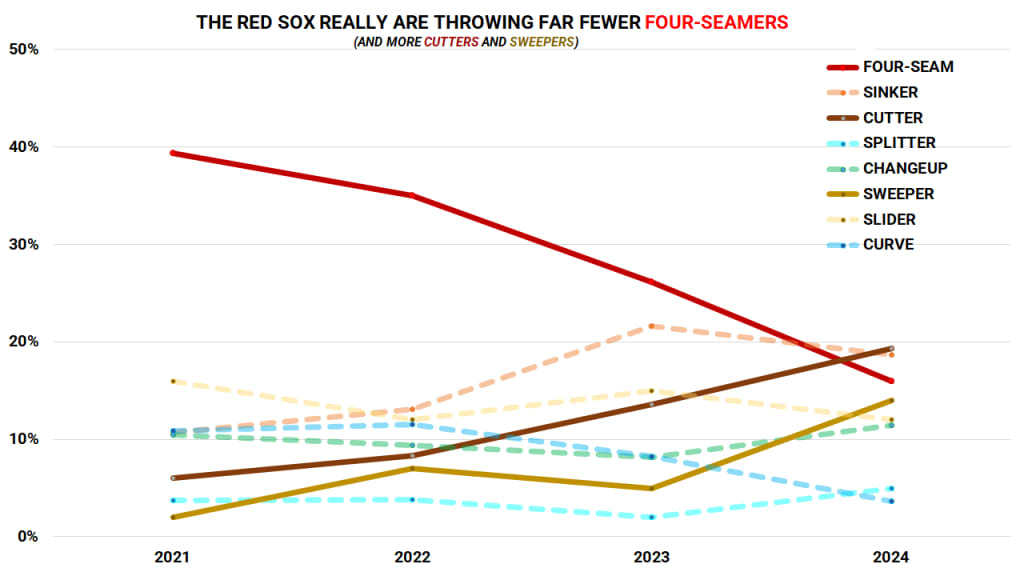

First, let's figure out what kind of fastballs we're talking about here. After doubling their sinker usage from 2021-22, that’s held essentially consistent ever since. Instead, it’s the four-seamers that are disappearing, down from nearly 40% of all Red Sox pitches in 2021 to just 16% this year, the lowest rate in baseball by a wide margin over San Francisco’s 22%.

Those missing four-seamers have been replaced by cutters (which are technically fastballs, but occupy a very different usage space, aside from Kenley Jansen) and sweepers. In 2021, those pitches were just 8% of all Boston pitches. In 2024, it’s 33%.

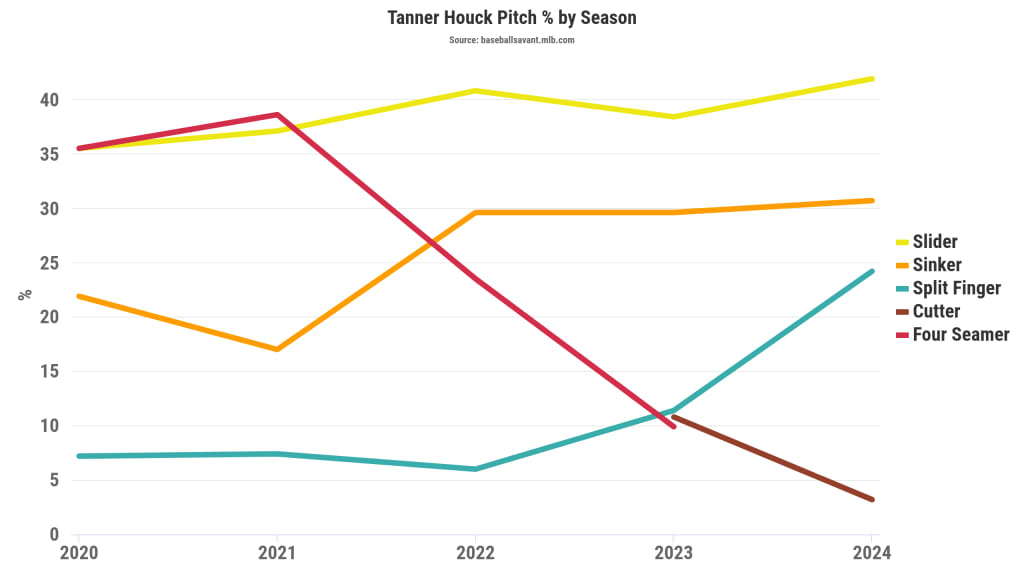

You can really especially see it when it comes to Tanner Houck, who has become an AL Cy Young candidate thanks to his 1.91 ERA. He’s still the sinker/slider pitcher he was when he first came up, except that the four-seamer that was once another primary pitch is completely gone, replaced by a new cutter and far, far more splitters.

Meanwhile, Bello allowed a .646 slugging percentage on the 540 four-seamers he threw last year, and hasn’t thrown it even one time in 2024.

So let’s focus on just the four-seamers, the bread-and-butter of pitchers for basically forever. In 2021, the Red Sox threw nearly 9,500 of them. This year, they’re on pace to throw only about 3,700. That’s a gap of nearly 6,000 missing four-seamers. Where have they gone?

To do this, you only need to know two different metrics -- velocity and movement -- and you already know one of them.

- Fastball velocity. No, we’re not explaining this. It’s fastball velocity.

- Induced vertical break, or IVB. A measurement of the movement of a pitch with gravity removed, comparing the movement of a pitch to a spin-free pitch at the same velocity. By taking all that out, the remaining movement should be due to the movement created by the pitcher. Getting over 20 inches is elite, top-of-the scale rise. Anything south of 10 is barely a four-seamer. (That’s right: Baseball really is a game of inches.)

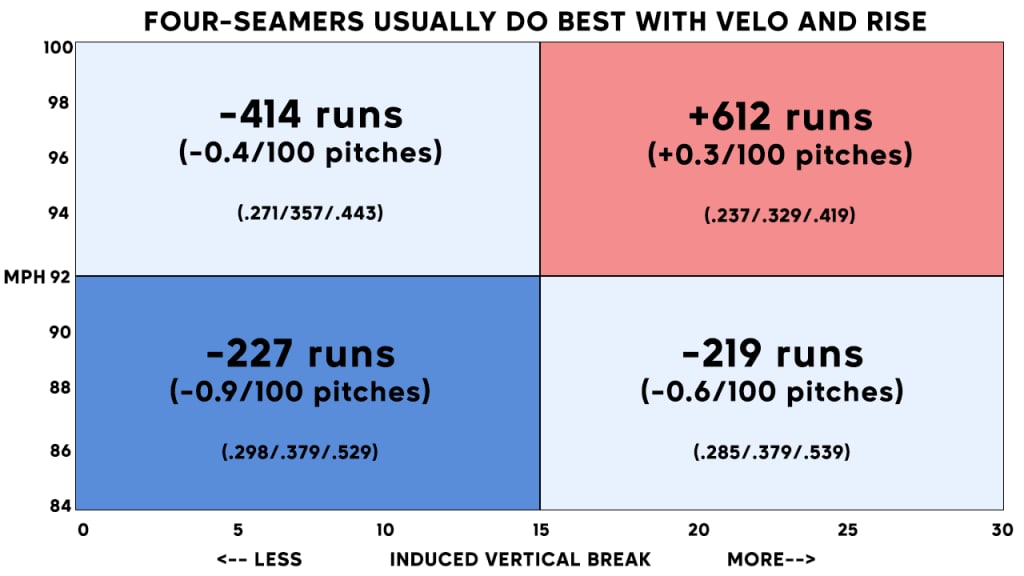

It’s not as simple as “throw hard and be good,” because we’ve all seen flamethrowers who couldn’t throw strikes. It’s not as simple as “have lots of rise, i.e. a high IVB, and be good,” because there’s never One Metric To Explain Them All. We're oversimplifying and ignoring pitch location and approach angles entirely here. But noting that there are always exceptions, you usually would prefer a pitcher who throws hard, and you’d usually prefer a pitcher with a strong IVB, and you’d really like one who can do both of those things.

That’s clear enough from this display of 2023-24 four-seamers, across all of MLB, showing combinations of velocity and IVB. It’s good to throw hard. It’s good to have a high IVB. It’s better to do both. (This is showing run value per 100 pitches, where red is good and blue is bad, for the pitcher.)

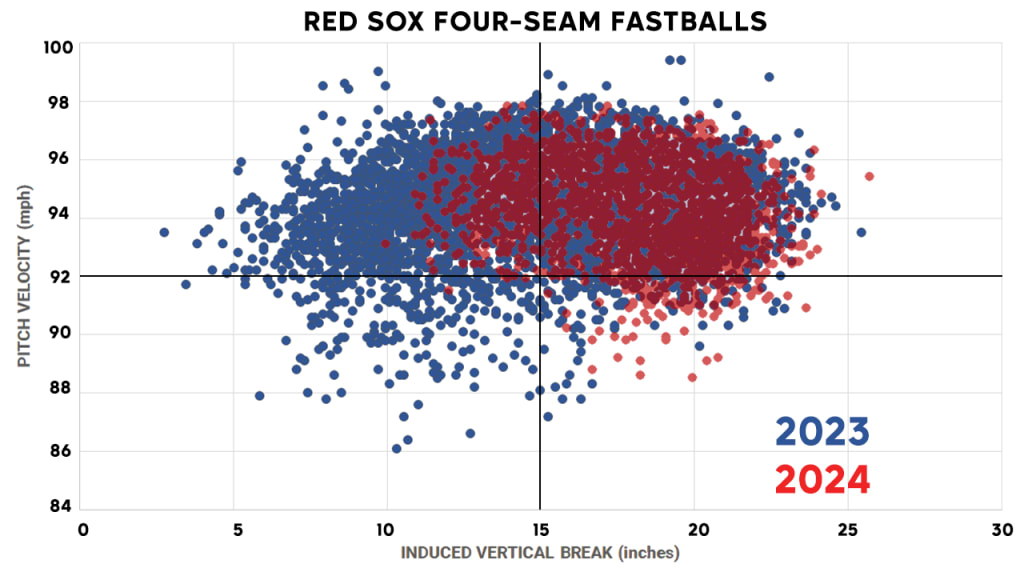

So, keep that shape in your mind, and take a look at all Red Sox four-seamers thrown in each of the last two seasons. Last year, they were sort of all over the place. This year, they’re much more tightly clustered in the “good velocity and impressive rise” area.

So, where have all those missing four-seamers gone? They fall into a few categories.

If your IVB is below 11 inches, don’t throw it. The Red Sox threw 868 of those four-seamers last year – just three this year – and those pitches allowed a line against of .275/.358/.492.

A huge chunk of these pitches last year came from the since-traded Chris Sale, who threw 381 of them and allowed a slugging percentage of .500 when he did. When he threw four-seamers with 11 inches or more of IVB, that slugging percentage dropped to .370. We should be clear that it’s not as simple as “a low IVB means a bad fastball,” in the same way that “low velocity doesn’t guarantee a bad fastball.” It’s just not hard to guess which side of that line you’d prefer to be on.

If your velocity is below 92 and your IVB is below 15 inches, don’t throw it. That’s the bottom left corner there. Boston threw 267 of those fastballs last year – just five this year – and the outcomes were awful, allowing a line of .280/.367/.620. That was Sale again, but also ineffective pitches from John Schreiber, Kyle Barraclough, Corky Kluber, Chris Murphy, and others.

If your velocity is below 92 and your IVB is at least 15 inches, do it sparingly. This is the bottom right corner, and the results here are quite poor: .284/.379/.539 (and -221 runs) across the Majors in 2023-’24. Boston doesn’t do this very much, just 137 times so far this year, and almost all of that is from Kutter Crawford. He’s actually done this a little more than last year, and the results aren’t great for him either.

If you already had velocity and movement, you’re fine. Let’s call this velocity of 92 mph or better and IVB of 15 inches or better. This generally leads to good production – .237/.329/.419 for pitchers, and +612 runs. This is ideally where you want to be, and this year, nearly 74% of Red Sox four-seamers fit this description. Last year, it was only 56%.

This is why some Red Sox pitchers haven’t changed, because they were already there – like Pivetta, who leads the sport in four-seam IVB (20.5 inches) and was already throwing his four-seamer in the good-velo/high-IVB zone 98% of the time last year. It’s why some were acquired, like Slaten, who was a Rule 5 pick from Texas (via the Mets) last winter, and has been a valuable reliever, with a 2.84 ERA.

He’s thrown 100% of his four-seamers – every last one – in that good/high zone, and if you don’t think he knows that, just look at how he described himself to David Laurila of FanGraphs in April:

“I’m a high vertical-ride guy,” said Slaten. “On average, I’m probably right around 17-18 [inches], but on my best days I’ll push it up to 20-21, sometimes 22. It’s a pitch that I have a ton of confidence in.”

They may be nerd numbers, depending on how you choose to observe such things, but they’re also exactly what the players on the field are using to succeed.

So: Is it working? At the end of the day, this is really all that matters. At a high level, Boston’s ERA is down from 4.52 to 3.43, which is a massive improvement – despite a defense that is still charitably described as “below average.” On four-seamers alone, they’ve improved from .257/.337/.477 against last year (18th best on a rate basis) to .199/.283/.327 (tied for sixth best).

The Red Sox, at 34-34 entering play on Thursday, are certainly pretty far from having Figured It All Out. But the pitching, clearly, is different from last year, and it's been better than last year. These things don't happen by accident. They happen by design.