In the most carefully documented of professional sports, Baseball-Reference.com is an essential deliverer of data, a credible companion to the curious and the compulsive. Its overnight updates during the Major League Baseball season ensure that player, team and standings pages accurately account for the latest avalanche of innings and outcomes. Every run, hit or error, every transaction, every analytical update, every morsel of mathematical minutiae is readily available to those who scour B-Ref, as it is colloquially known.

And so, much like the monumental Major League embrace of Negro League statistics this week, it is notable that, in the year 2020, Baseball-Reference has added three new entries to its long log of no-hitters.

The first two are obvious. Even in a season sans fans in the stands, Cubs right-hander Alec Mills’ Sept. 13 shutdown of the Brewers and White Sox right-hander Lucas Giolito’s Aug. 25 domination of the Pirates attracted ample eyeballs and are included as a basic matter of course.

But only the most ardent examiner of these notated no-nos would notice the third addition, buried at No. 249 in reverse chronological order:

Pete Dowling, Cleveland, June 30, 1901, at Milwaukee.

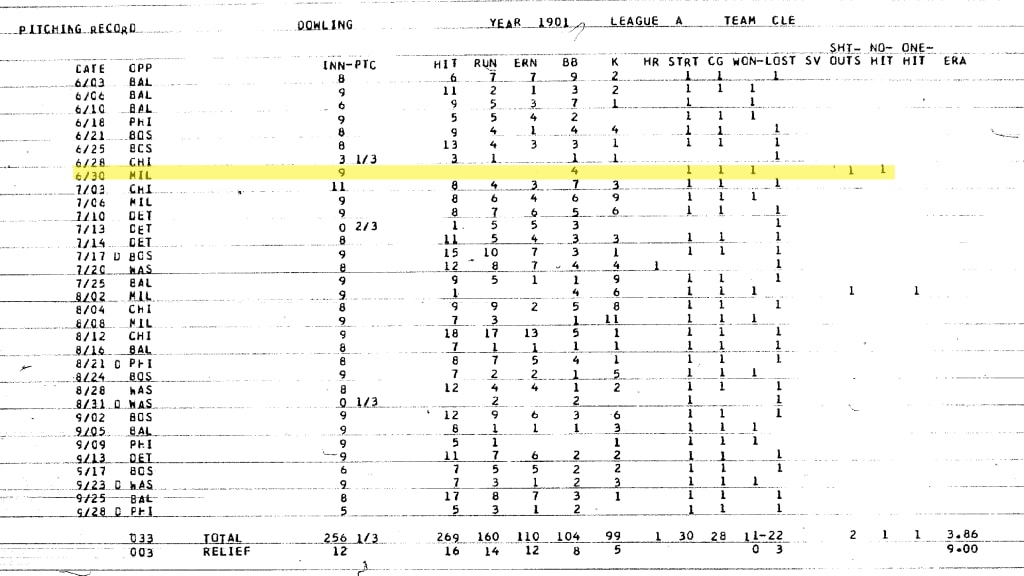

Read the pitching line attributed to Dowling’s effort that day, and it seems pretty straightforward. He threw nine innings, and he allowed four walks with no strikeouts, one hit batter and -- this is the important part -- no hits.

Yes, this would appear to fit the basic definition of no-hitter -- one of the game’s most celebrated individual achievements. And even beyond the enticement of no-hitters, in general, this one would have particular significance as the first in the history of the American League.

So, why are we just finding out about this now? How did Dowling get this HTML update, more than 119 years after his supposed achievement and 115 years after his death? Why was B-Ref bereft of this information until very recently?

A decades-long research effort by an organization called Retrosheet, which provides much of the box-score data used by Baseball-Reference, and a new research article by Society for American Baseball Research author Gary Belleville holds the answers to those questions.

But because truth is ever ethereal, even baseball’s most trusted internet encyclopedia is open to interpretation on this one.

* * * * *

Here’s what we know for sure: In 1901, a left-hander named Pete Dowling began the American League’s inaugural season with the Milwaukee Brewers (the charter junior-circuit franchise that would relocate the next season as the St. Louis Browns and eventually settle in Baltimore as the Orioles). On June 1, Dowling’s contract was sold to the Cleveland Blues (who would later become the Indians and will soon become something else). And on June 30, in the opener of a three-game series in Milwaukee, on a scorching Sunday afternoon, Dowling beat his old team, going the distance in a 7-0 victory.

We also know that, in the seventh inning of this game, a Milwaukee batter named Wid Conroy reached base.

What we don’t know is whether Conroy reached on a hit or an error.

Until the summer of 2020, there was no easy way to know. Nor was there any reason to care. The Dowling game was one of many from an early period of American League history for which official records were not kept, and the only available information for Dowling’s game on Retrosheet -- and, by extension, Baseball-Reference -- was a line score, excluding hits and errors.

For the last 31 years, however, Retrosheet has sought to fill in baseball’s blanks, of which there were -- and are -- many. A University of Delaware biology professor named David Smith started the organization in 1989, in an effort to uncover lost information, to create an accessible database and to point out disparities in the records.

“The practice for most of Major League Baseball for almost 100 years was the official scorer would keep track at the game and fill out a written report that was sent to the league office,” Smith says. “Once it arrived at the league office, somebody would transcribe the report from the individual game into a giant ledger book. So if a guy had four at-bats, scored a run and struck out twice, that would be recorded. There was no official play-by-play.”

One can see where holes could develop in this process. If the official scorer made a scoring change the day after a particular game, it might not necessarily be reflected in the report sent to the league. Or human error in the handwritten notations either by the scorer or the league official could affect the official totals.

So while the ledger pages, which were bound in heavy volumes and eventually transferred to the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, are considered “official,” they are not necessarily accurate.

That’s where Retrosheet stepped in, with a focus primarily on games that took place prior to 1984, when game information was not relayed from the press box to the league office in “real time.”

Retrosheet, true to its name, began working backward, beginning with the early 1980s and then venturing further back in baseball time. An army of roughly 100 volunteer researchers reconstructed box scores by scouring all available evidence. This included newspaper articles, radio and television recordings and team scorebooks. In more recent years, Retrosheet has even managed to find new information from vintage fan scorecards offered on eBay.

What have they found?

“For most of the seasons,” Smith says, “we have found about 2,000 discrepancies per season.”

That wording is important. Smith refers to them as “discrepancies,” not “errors,” because he acknowledges the imperfections of this process. Perhaps the newspaper reports are inaccurate or contradict each other. Perhaps the scorecards have mistakes. Perhaps Retrosheet itself inputs an outcome incorrectly.

Truth can be tricky.

Anyway, the result of this painstaking process to identify discrepancies is that Retrosheet has pieced together the play-by-play for every Major League game going back to 1928. Again, no claim is made that these are ironclad accounts. Many are what Smith calls “deduced games,” constructed through newspaper stories or broadcasts or other means. But it’s a far cry better than what we had before.

That said, Retrosheet’s system presupposes an official record as a point of comparison. Alas, for the first four seasons of the American League -- from 1901-04 -- there is no existing official record. The only source for anything resembling official stats from those years was the 6 1/2-pound behemoth of a book called “The Baseball Encyclopedia.”

Published by MacMillan (and therefore lovingly referred to as the “Big Mac”) the book was Baseball-Reference before Baseball-Reference. A team of researchers from a company called Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI) had scoured newspapers, under enormous time pressure, to put the first "Big Mac" together in time for its 1969 publication. And it is in that very first edition of the "Big Mac," on the bottom of page 1,812, that a small note is made in Pete Dowling’s entry:

“No-hit game vs. MIL A, June 30, 1901.”

* * * * *

Much like MLB’s official ledgers, the records compiled by ICI’s researchers have been microfilmed by the Hall of Fame Library. Retrosheet has used them as the point of comparison for its own research.

Dowling’s 1901 game log compiled by ICI could not be more clear. In the “No-Hit” column, there is a “1” listed for the June 30 outing. And yet, the 1969 edition of “The Baseball Encyclopedia” is the only one to credit Dowling with the achievement. Subsequent editions do not include it.

How could that be? Well, in his research on the issue for SABR, Belleville cites a 2014 observation from official MLB historian John Thorn.

“The data reported by the ICI group in the first edition of 'The Baseball Encyclopedia' upset many people in baseball, for their numbers were different from those traditionally accepted,” Thorn had written. “In subsequent editions, many of the prominent players’ statistics were fudged back to their traditional values.”

So, yes, it is reasonable to deduce, as Belleville did, that the sudden arrival of a “new” no-hitter in 1969 ruffled some feathers and was removed.

It is, however, also possible that the ICI researchers found the same inconsistencies that Retrosheet did when it pored over newspaper reports from this game many decades later. Conroy’s seventh-inning advance to first base is described differently depending on the outlet, as Belleville details in his piece.

A wire service report that was published in the Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, Philadelphia Inquirer, Detroit Free Press, St. Louis Republic, Baltimore Sun and other newspapers noted that Dowling had limited Milwaukee to “but one scratch hit.” That hit is described as “a hot drive by Conroy to [third baseman Bill] Bradley, who could not handle it in time to put the runner out.”

The Cleveland Plain Dealer (which, as was standard at the time, had a non-staff stringer covering the road game) ran the headline, “Only One Scratch Hit.” Conroy is credited with a hit in the accompanying box score.

Interestingly, the only description of Dowling’s gem as a no-hitter comes from a paper based in the city in which the game was played. The Milwaukee Journal’s July 1 headline reads, “Dowling Gets Even; Former Brewer Does Not Allow [Hugh] Duffy’s Men a Hit or a Run.” The box score shows no hits for Conroy and an error for Bradley. The game story describes the play as follows: “Conroy hit a hot one to Bradley, who let it get away from him. … However, he had plenty of time to recover himself but failed and Cleveland’s only error resulted.”

Here's another instance in which one can surmise, as Belleville did, that the game was scored by a Milwaukee sportswriter and that a scoring change on this play was made after the game had concluded. If the change was not communicated to the writers working for the wire service or the Plain Dealer (or if they had already filed their pieces and did not issue corrections), it would explain why the local paper would be the only one to recognize Dowling’s no-no.

While it is incomprehensible that a scoring change resulting in a no-hitter wouldn’t set off alarm bells in the present day, it is possible that such a decision would be given little attention in 1901.

“No-hitters had not yet achieved the lofty status they held decades later,” Belleville writes.

Still, the reports are incongruous enough to cast a shadow of a doubt over Dowling’s supposed no-hitter. The Plain Dealer’s 1901 season review boasted of his two one-hitters, as did the 1902 Reach Base Ball Guide. The only place where any baseball fan would have any reason to think Dowling had tossed a no-hitter would be Milwaukee -- a city that lost its team at the end of 1901 and didn’t get a replacement for more than a half-century.

So Dowling’s legacy did not survive long. And he died exactly four years to the day after that outing against Milwaukee. Per SABR’s research, he missed his train at Fox Lake station in Union County, Ore., while trying to make it to the game of a semipro team he had just joined. Dowling decided to walk along the railroad tracks and was decapitated when he was struck by an oncoming train.

That gruesome death would have been the end of Dowling’s story if not for Retrosheet’s research. On July 12, 2020, when Retrosheet dumped a fresh batch of stale data on its website, there among the box scores was the June 30, 1901, game between Cleveland and Milwaukee. It has a zero in the Brewers’ hit column and an error attributed to Bradley.

Smith, for one, doesn’t deem the discovery to be any more revelatory than any other “discrepancy” uncovered by Retrosheet’s work.

“It doesn’t float my boat very much,” Smith said. “It’s another game. They all matter. Every ground ball to third base matters. I want them all right. There have been over 200,000 games played since 1901. We have some form of play-by-play for over 190,000 of those 200,000. I want them to all be perfect.”

Belleville, who stumbled upon Retrosheet’s newly updated list of no-hitters while investigating no-nos for SABR's Baseball Research Journal, was understandably more excited about the revelation. His ensuing explanation is a worthwhile read, and his own research is thorough.

But for now, the only relevant sources that are listing the Dowling game as a no-hitter are Retrosheet and B-Ref. And because one uses the data of the other, that essentially amounts to a single source -- Retrosheet, which is giving Dowling the benefit of the doubt.

“I looked at this a lot,” Smith said, “and I finally decided, yeah, it’s more likely than not that it was a no-hitter. That’s why we have it as a no-hitter.”

Not everyone agrees.

A representative from the Elias Sports Bureau, which serves as the official statistician of Major League Baseball, told MLB.com it is not adding Dowling to its list of no-hitters. Similarly, the Cleveland team will only be listing Dowling’s game as a “near no-hitter” in its 2021 media guide.

If a Cleveland pitcher were to throw a no-no in 2021, therefore, it would be officially recognized as the 15th in franchise history, not the 16th. The first in Cleveland franchise history is still attributed to Bob Rhoads (Sept. 18, 1908, vs. Boston) and the first in American League history is still attributed to Nixey Callahan of the White Sox (Sept. 20, 1902, vs. Detroit).

So, as with so much else in our polarized populace, whether you consider Dowling to have thrown the AL’s first no-hitter is dependent on where you get your information from. We have evidence that he no-hit the Brewers on June 30, 1901. We have just as much evidence that he did not.

What we don’t have is the truth.