We’ll admit that the names Jacob Young, Michael Siani and Daulton Varsho aren’t exactly “Willie, Mickey and the Duke,” as far as these things go, but when you realize what they’re at the forefront of right now, you might reconsider how you think about their names – or really, you might begin to think about them at all.

What if, when we talk about the difficulty in stringing hits together in today’s game, we’ve understandably put entirely all the focus on pitch velocity, spin-heavy sweepers, and the infield shift (RIP), and in doing so, what if we’ve overlooked something key: What if we’re living in the Golden Age Of Outfield Defense?

There’s no great way to prove that out across the eras, to clearly make the case that today’s outfielders are the defensive equal of, say, Willie Mays and Andruw Jones, but that’s also not the point we’re trying to get to today. We have decent data for most of the 21st century, good data since Statcast tracking came online in 2015, and excellent data since a 2020 hardware upgrade. We can just focus on those timeframes.

No matter which version we use, the story comes back the same: Outfielders are simply catching more and more of the opportunities hit to them. For all the attention paid to the restrictions on the infield shift, the real difficulty hitters face is that even if you manage to make contact against the increasingly dominant pitching they face every night, and you hit it hard enough to get it beyond the infielders, it’s harder and harder to figure where on the outfield grass you might actually find a hit.

It’s no surprise, then, that many lineups have become so homer-reliant: Over the fence is the one place that talented defenders can’t take a hit away from you. (Well, most of the time.)

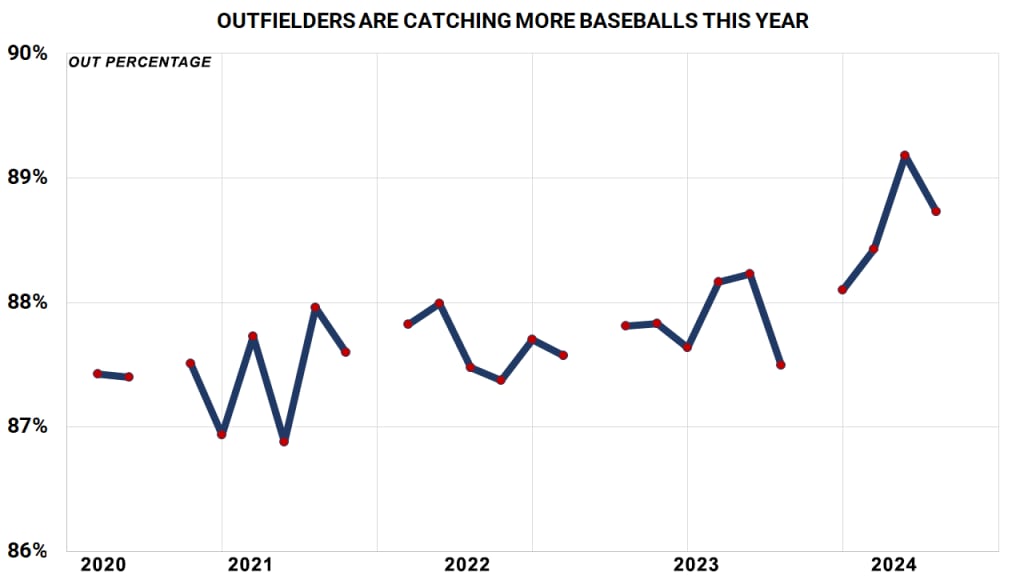

Consider this, looking at every regular-season month from 2020 through the end of July 2024, focusing on simply how many opportunities outfielders turned into outs. Even with a mild step back in July, the top three months for outfielder conversion rate were in 2024 – June, July and May, in that order – and April was sixth-highest, behind only two months from last summer.

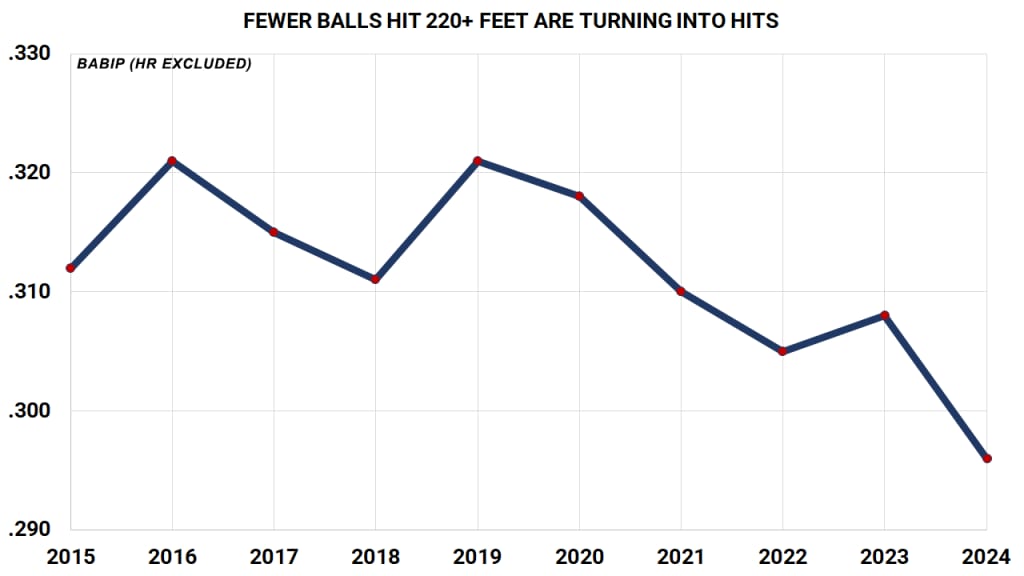

But OK, maybe the last five years aren't enough to convince you. Let’s go back to 2015, so nearly 10 full seasons now, and just look at batting average on balls in play (or BABIP) on balls hit at least 220 feet (removing, obviously, home runs), which is a good dividing line between infielders and outfielders.

Even with the restrictions on third basemen playing in short right field, the hits have dropped.

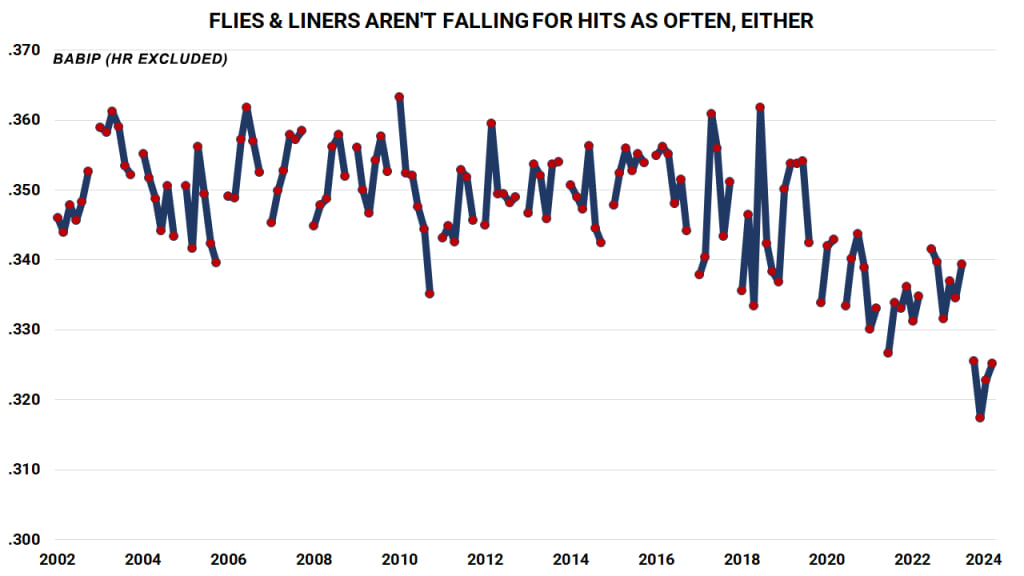

A whole decade not enough? We don’t have Statcast prior to 2015, but we do have human-entered batted-ball types going back to 2002. Looking at BABIP non-grounders isn’t perfect – we’ve now included some number of line drives to infielders, surely – but it’s what we’ve got, and the story is no different. There have been 133 months since 2002 through the end of July.

Guess which season has the four lowest BABIP months? (It's the most recent four.)

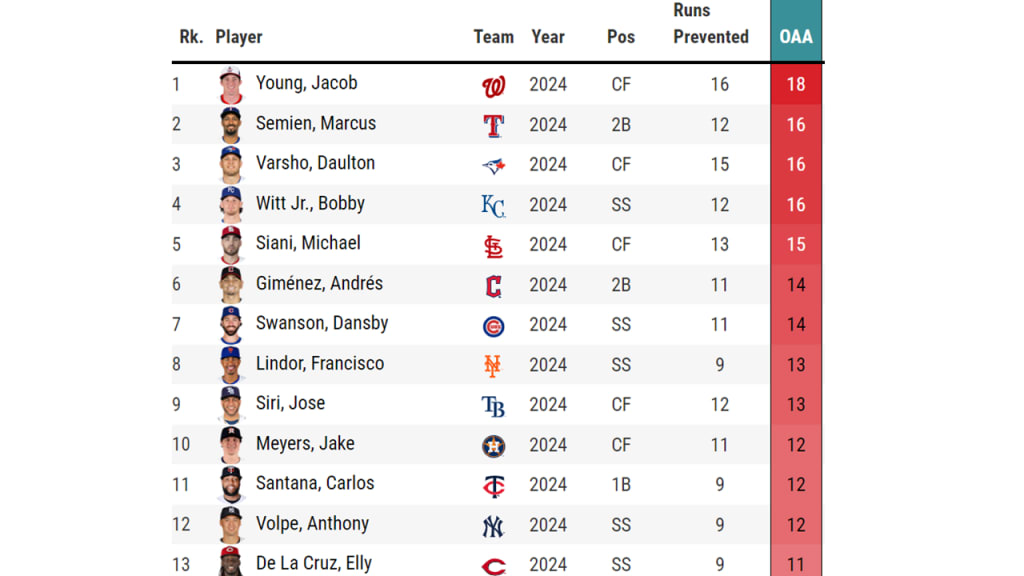

The trend, no matter how you look at it, is clear, and at the forefront, at least in 2024, are the aforementioned trio of defensive stars. How are they doing it?

Jacob Young, Nationals

Young isn’t just having a strong defensive season, he’s having an elite one, leading the Major Leagues in Outs Above Average – making him highly likely to become just the 18th player to win a Gold Glove as a rookie. This, after not even making the Opening Day roster, as the Nationals chose to go with the defensively limited Eddie Rosario as a surprise center fielder.

It’s not with elite and crisp routes, that’s for sure – Washington’s rookie outfielder rates dead last in route-running, believe it or not. But he has the quickest reactions (feet covered in the first 1.5 seconds), and 97th percentile Sprint Speed, and ultimately he gets off to the best jumps in baseball (feet covered in the right direction in the first three seconds), just ahead of Varsho and Kevin Kiermaier – who we argued last summer was legitimately one of the best outfield defenders to ever live.

It’s all reminiscent of Jackie Bradley Jr., himself a long-time elite defender, who also prioritized outstanding reactions over line-perfect routes on his way to becoming one of the best defenders of his generation.

Daulton Varsho, Blue Jays

"He's the best defender in all of baseball, and no one's even close,” Blue Jays pitcher Chris Bassitt told SportsNet, a claim echoed by their manager. "I've said it a million times: he's the best there is," Toronto manager John Schneider said.

OK, so maybe Varsho’s defensive acumen isn’t exactly under-the-radar, at least north of the border, though it’s worth noting he’s yet to receive a Gold Glove. That’s despite leading all outfielders in OAA (45) over the last three seasons by a large gap over second-place Jose Siri (37). Varsho has strong but not elite speed, rating in the 79th percentile this year. Like Young, his reactions are elite – they’re basically tied in getting good jumps – though Varsho makes up for the slightly lesser speed by taking more accurate routes.

Michael Siani, Cardinals

Before his rookie season was cut short by an oblique injury, Siani spent most of the year leading outfielders in OAA, and the profile here is similar: strong-not-elite speed (78th percentile), average-ish route-running and elite reactions and jumps. If it’s not clear what the key to good outfield defense is yet, it's this: Get moving as soon as you can. If you don’t, the flip side here is someone like Cleveland’s Tyler Freeman, who has similar speed to Siani and Varsho, but with a -3 OAA in center due to nearly weakest-in-baseball jumps (which aren’t surprising for a player converted from the infield this year).

It goes on and on, really. Throw a dart and you’ll hit an outfielder we haven’t highlighted here, whether it’s veteran defensive stars like Kiermaier or Harrison Bader, underrated fielding studs like Kyle Isbel or Jake Meyers, or up-and-coming young players like Blake Perkins or Brenton Doyle or Colton Cowser or Pete Crow-Armstrong – or Young and Siani.

So what’s going on here across the bigs to grow such a crop of defensive dynamos?

One way to approach that question is to try to figure out if it’s more that the players are better or it’s just easier to make plays, whether via positioning or strategy or the way the ball is playing.

Since we already know more balls are being caught, we can attack the second part of that question by asking if more balls should be expected to be caught. That is: We know teams have become more and more sophisticated in terms of positioning their outfielders – we’ve all seen players checking their cards. If the opportunities have simply become easier due to less distance to travel, then maybe the players aren’t actually performing better – maybe it’s just that they have been placed in better situations.

That, however, does not seem to be the primary case. The expected catch rate, based on distance, time, and in some cases direction + wall, has gone up ever so slightly each season, maybe .1% annually. That’s bigger than it sounds, over 35,000 or so outfield plays a year, and positioning should be considered responsible for a few dozen outs per season. (There is evidence that positioning took a larger jump starting a decade ago, but it also seems possible that many of the gains have already been realized.)

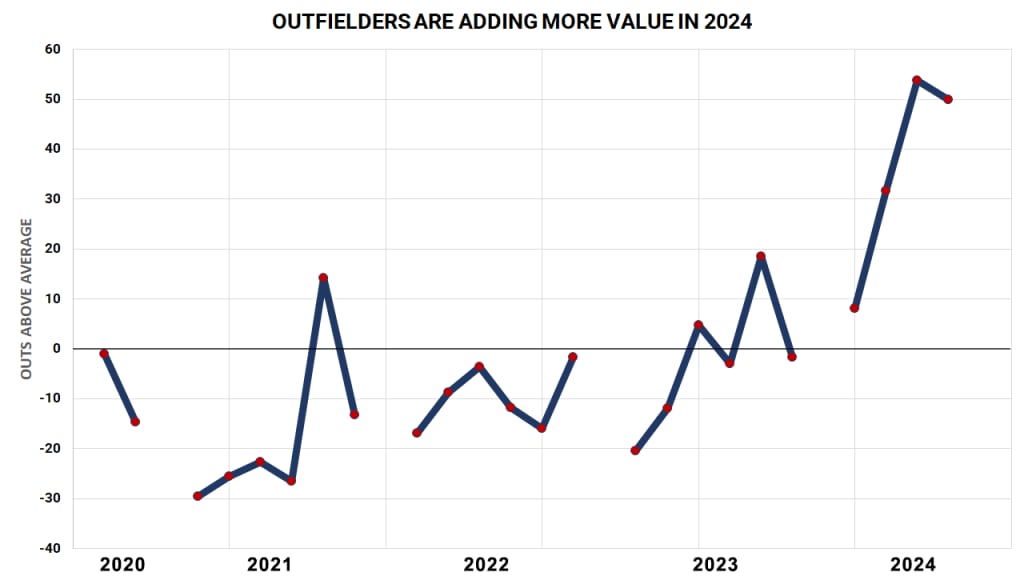

But the actual performance of outfielders far exceeds that, and it’s easy to show. The OAA you’re used to has the “above average” part of that phrase being “for that season.” If we look at a version that treats the last five years as one big group, provided by MLB.com’s Tom Tango, it’s pretty easy to see what’s happening here. The opportunities are maybe getting a little easier, but the quality of fielders seems to be getting a lot higher. (This would account, too, for the possibility of lazier, higher fly balls from hitting approach.)

In other words, outfielders in 2021 posted a -103 OAA, compared to the full half-decade span. It was a little better in 2022 (-58), and coming up on even in 2023 (-13), with a notable in-season improvement (-19 in the first two months, followed by +32 for the final four) and it’s been tremendous in 2024 (+143).

It’s not hard, at least, to guess why the fielders might be better. For one thing, the National League now has the designated hitter, giving more homes to bat-only players like Marcell Ozuna and Kyle Schwarber who in the past have had to play the field with underwhelming results.

For another, as the Majors have trended more toward youth and speed, slower players get less time in the outfield. This is “the Ryan Doumit theory,” for those of you old enough to remember what happened when pitch framing took over the catcher position a decade ago, and good-hitting poor-receiving catchers were slowly phased out of consideration.

It’s like that here, too. There have been 45 times since 2016 that an outfielder has posted -10 OAA. Thirty of those years happened in the first four full seasons, 2016-19. Only 14 have happened in the last four full seasons, 2021-24 – and two were by Schwarber, playing the field because the needs of the Phillies required it – though we may get a few more before 2024 ends, depending on how the Mets divvy up playing time between Starling Marte and Jesse Winker.

Or, if you prefer, just look at Sprint Speed by position, weighted by playing time, comparing 2016 to 2024. While left field has stayed steady, it’s notable that both center and right has seen the average speed of outfielders increase.

Sprint speed, weighted, comparing 2016 to 2024 (ft/sec)

- LF 27.5 → 27.6 (+0.1)

- CF 28.3 → 28.7 (+0.4)

- RF 27.4 → 27.7 (+0.3)

On a completely related note: The average center fielder in 2016 was 27.6 years old. The average center fielder this year is 26 years old. Only 4% of center field plate appearances have come from players 30 or older -- the lowest full-season rate in the pitch tracking era (2008-pres.) and exactly one half of what it was back in 2016-17.

We’ve seen this a number of times over the years, that once something can be quantified, teams and players work toward improving it. It was, and has been, happening with pitch velocity for years. But a decade ago, it was pitch framing. Then it was spin rate, and then pitch movement and seam-shifted wake, and maybe now it’s starting to happen with bat speed.

But it’s speed, and defense and outfield reactions, too. Positioning is almost certainly more effective than it was a decade ago. That alone isn’t why it’s so hard to find hits in the grass, however. It’s because the athletes playing out there are more skilled than we’ve seen on any recent record – and, though we’ll never know for sure, perhaps ever.