Ron Teasley never dreamed of being a so-called “big leaguer” in the American or National Leagues.

He wanted to be a Negro Leaguer.

Growing up in Detroit in the 1930s, Teasley would listen to Tigers games on the radio and was a big fan of star second baseman Charlie Gehringer. But for reasons Teasley did not yet understand, his father kept him away from Tiger Stadium (then known as Navin Field), where their skin color would have limited them to the segregated sections. Teasley was steered instead to home games of the Negro National League’s Detroit Stars and, after that club disbanded, to traveling exhibitions featuring Satchel Paige, Turkey Stearnes and other Black stars of the era.

“My dad was a big fan of Negro League baseball,” the 97-year-old Teasley told MLB.com last year. “I would hear a lot about the Negro Leagues. We’d play catch, and he’d talk about some of the outstanding players. Then I gravitated to sandlot baseball and T-ball.”

Teasley proved talented enough to live out his dream, suiting up for the Negro National League’s New York Cubans as a utility man in 1948.

It was not until 72 long years later that Teasley learned his time with that team does, indeed, qualify him as an official big leaguer. In December 2020, MLB announced that it was finally, formally recognizing seven professional Negro Leagues that operated between 1920 and '48 as a part of Major League history.

That announcement has statistical ramifications for thousands of players, the vast majority of whom have passed away.

Thankfully, three players from the selected leagues and seasons are still with us -- Willie Mays, Bill Greason and Teasley.

We’ll go out on a limb and assume you’ve heard of the 92-year-old Mays, whose time with the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League is now added to the 2,992 regular-season games he played for the New York and San Francisco Giants and the New York Mets.

The 99-year-old Greason, a right-handed pitcher who went on to become a Baptist minister, was on that same Black Barons team as Mays. Greason’s Negro Leagues totals from that season have been added to the four innings he pitched in a brief stint with the 1954 St. Louis Cardinals.

But the living person for whom MLB’s overdue embrace of the Negro Leagues is most meaningful is Teasley. He is, after all, the only one of the three living players who did not play in the American or National leagues, despite signing a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers early in 1948 and spending part of that season with their farm team in Olean, N.Y.

“Me and another player named Sammy Gee were invited to a two-week tryout in Vero Beach [Fla.],” says Teasley, who had played for Wayne State University and served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific during World War II. “They signed us and sent us to Olean. I thought we were playing outstanding baseball. I was batting, I think, .270, and Sammy was batting .300. But one day they came up and said they had to make a move for players from a higher classification and released us.”

That’s how Teasley wound up in the Negro National League. The scant available numbers credit him with two games played, seven at-bats and two hits (including a double) for the Cubans. Though Teasley says he played much more than that in his roughly two months with the team, he’s grateful that any record exists of his time in the Negro Leagues and that this participation will now be recorded in the MLB annals.

“It’s always nice to be recognized and remembered for your services and your achievements,” Teasley said.

A committee of researchers and historians worked to ensure more than 3,300 Negro Leagues players from the relevant years and leagues received that recognition in the official MLB statistical database maintained by the Elias Sports Bureau. It has been a detailed, demanding and difficult process -- but one that recently received the organization and cohesion it needed to give players like Teasley their due.

* * *

A pivotal piece of the story behind the Negro Leagues numbers that will one day be included in the MLB register begins at a Duke University library around 1999.

An English graduate student named Gary Ashwill was scouring the microfilm stacks while working on his dissertation on race and imperialism in 18th- and 19th-century American literature when he happened upon old editions of the Chicago Defender, an influential Black newspaper that began publication in 1905.

Ashwill was -- is -- a rabid baseball fan who devoured the annual Bill James Handbook and collected various baseball encyclopedias. The scarcity of information about the Negro Leagues in those texts -- as well as the slow drip of stats from the 1921 and '30 Negro National League seasons that researchers Dick Clark and John Holway published in the Baseball Research Journal -- tantalized him. Ashwill was curious about the heroes of Black baseball and what their numbers must have looked like.

The Defender discovery intrigued him. The dissertation work, which to this day remains incomplete, went off to the side so that Ashwill could dive deeper into the Defender’s sports coverage.

“I had this idea that there wasn’t any way to compile statistics for the Negro Leagues,” Ashwill says. “I was under the impression that I was not going to be able to do very much.”

What he found, instead, was fairly detailed coverage of the Negro Leagues -- not just in the Defender, but in other Black press such as the Baltimore Afro-American and the Pittsburgh Courier. Or at least, as detailed as could be crammed into two or three pages in a 20- to 24-page edition of a weekly paper.

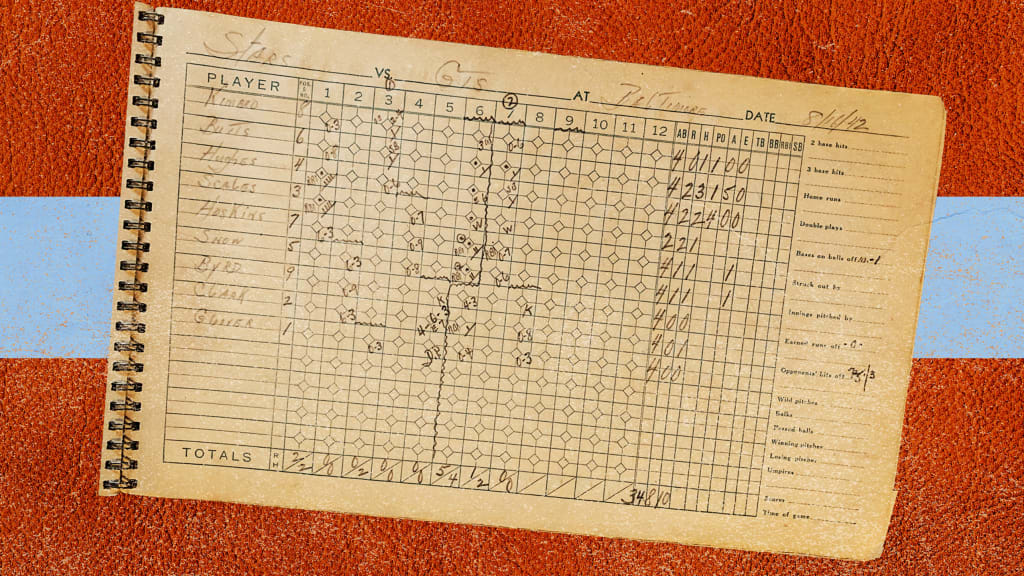

Ashwill found scores of box scores and game recaps, and he began paying the 10 cents per page to print them out. He had no plans for the material; he just instinctively collected it, then learned how to input it into computer spreadsheets.

In the ensuing years, Ashwill, a freelance editor, began to post some of his findings to a Society for American Baseball Research e-mail forum, then the Baseball Think Factory’s Hall of Merit site. He was invited to assist the Negro Leagues Researchers and Authors Group, which at the time was gathering stats for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. And in 2006, he launched a blog called Agate Type, where he wrote posts on Negro Leagues players and presented his statistical findings.

Ashwill found volunteers to help him with research work, which is made difficult by gaps in what was reported and man-made errors by those reporting it.

Ultimately, though, it has been rewarding work.

“Increasingly, I discovered there was more stuff out there than I thought,” Ashwill says. “That’s a constant in my time working on this.”

Kevin Johnson, Ashwill’s friend and fellow researcher, suggested that the spreadsheets be organized online, and that’s how the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database was created in 2011. While the nature of the Negro Leagues ensures that the data will never be comprehensive (and we’ll delve into some of the specifics of that shortly), Seamheads became the go-to source for by far the most complete and readily accessible statistical record of the Negro Leagues.

When MLB made its announcement about formally recognizing the Negro Leagues as Major Leagues, Ashwill, Johnson, Scott Simkus and Mike Lynch of Seamheads were specifically commended for the research work that would form the backbone of the effort to incorporate the Negro Leagues numbers.

“That was crazy, it really was,” Ashwill says. “I was up pretty late that night talking to people, doing lots of interviews. It was a weird thing, because this is something I had been doing for years in a smallish community, and you’re not thinking about the public at large.”

Immediately, though, the public at large began to pore over the data available at Seamheads. And soon thereafter, Baseball Reference -- the high-traffic, highly cited website used by major media organizations, baseball broadcasts and fans as a source of statistics -- went from housing a small portion of the Seamheads data on its site to folding the Negro Leagues numbers into the Major League historical record.

So for the past few years, if you went to B-Ref’s career batting average page, for instance, there was all-time leader Ty Cobb (.3662), followed immediately by Negro Leagues legend Oscar Charleston (.3648).

“It’s a little surreal to see that,” Ashwill says. “It’s weird to think that, if I had found an extra game, that number [listed] there would be different.”

But as influential as Baseball Reference might be, it is not the actual MLB register. The league’s official statistician -- and, ergo, the keeper of the official database -- is the Elias Sports Bureau, as official MLB historian John Thorn explains.

“MLB’s position has been that, while there are Negro League stats at the Seamheads database or Baseball-Reference.com, we cannot be in the position of importing bulk statistics from a third party without auditing,” says Thorn. “That’s where Elias comes in, and that’s where I come in.”

And that’s where the path to the Negro Leagues joining the Major League register truly began.

* * *

When Sean Gibson’s phone suddenly became flooded with the texts and calls on Dec. 16, 2020, he was floored. The great-grandson of the legendary Josh Gibson had no idea the MLB announcement about the incorporation of the Negro Leagues was coming.

“Nobody in the Negro Leagues family knew,” says Gibson, who serves as the executive director of the Pittsburgh-based Josh Gibson Foundation. “For us, we always felt like our relatives were Major Leaguers, anyway. As I’ve always stated, Josh would have loved to play in the Major Leagues, but [then-Commissioner] Kenesaw Mountain Landis prevented the opportunity. When people discredit Negro Leaguers’ level of talent and their leagues, well, they had to play where they had to play. It wasn’t their choice.”

In 1968 and ‘69, MLB’s Special Committee on Baseball Records was convened by then-Commissioner William Eckert to determine which past professional leagues should be classified alongside the American and National Leagues as Major Leagues in the first publication of “The Baseball Encyclopedia.” The committee ultimately concluded that the American Association (1882-91), Union Association (1884), Players’ League (1890) and Federal League (1914-15) qualified.

It's not that the Negro Leagues were discussed and ruled unworthy of inclusion. Worse: The Negro Leagues didn’t even come up in the meetings. They were ignored completely.

“Like the title of the book by Ralph Ellison,” says Thorn. “Invisible Man.”

The announcement in 2020 ensured the Negro Leaguers, all these decades later, would finally be visible. But drawn-out discussions between MLB and Seamheads over how the data would be utilized further complicated an already challenging process. It was not until earlier this year that a deal was reached, allowing MLB to proceed with building upon the Seamheads database with the help of Retrosheet -- an organization that computerizes Major League games from prior to 1984 -- and then verify everything with Elias.

Once the Seamheads deal was in place, MLB was able to assemble a committee of researchers and statisticians to determine the statistical parameters for what -- and what would not -- be admitted into the official record.

The 15-person Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee, overseen by Thorn and members of MLB’s communications department, held its first meeting over Zoom in early September 2023. It includes Sean Gibson; Ashwill; author Phil Dixon; MLB Players Association representative Jeff Fannell; Kent State professor and author Leslie Heaphy; Seamheads Negro Leagues database researcher Kevin Johnson; Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick; Elias Sports Bureau director of research John Labombarda; author and researcher Larry Lester; Jackie Robinson Foundation director Sonya Pankey; MLBBro.com founder Rob Parker; MLB chief baseball development officer Tony Reagins; former big league pitcher CC Sabathia; National Baseball Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber; journalist Claire Smith; and Retrosheet president Tom Thress.

“I’m glad they put this committee together,” Gibson says. “It’s top-notch. This is a start to get some recognition for these players, and the statistics for Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell and so many great players will be in the record books.”

Gibson’s great-grandfather is the perfect example of how important specificity is in this process.

Josh Gibson’s Hall of Fame plaque states that he “hit almost 800 home runs in league and independent baseball during his 17-year career.” Were that number verified and all of those games counted in the official record, Gibson would likely surpass Barry Bonds’ record total of 762 career home runs.

“When this announcement first came out, my phone was ringing off the hook with people saying, ‘Josh is going to be the home run king now!’” Gibson says with a laugh. “I thought so, too, because I didn’t know how this whole thing worked.”

Only the statistics associated with verified games that are determined to be Major League caliber will be counted in the official record. The committee was faced with two major tasks -- verifying the Seamheads data, and then determining what to leave in and what to take out.

* * *

MLB made its Negro Leagues announcement on the heels of a 2020 season that was shortened to 60 regular-season games due to COVID-19 restrictions.

As it turns out, the 2020 season provided a guide for the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee to follow in determining what minimums must be met for a Negro Leagues player to qualify for Major League single-season records.

“We have to create baselines,” says Thorn, “that do not leave us with absurd results, with the single-season ERA leader having 30 innings pitched or guys who played in 18 games and had fewer than 100 at-bats being listed among the .400 hitters. I think an interesting place we landed was when Major League Baseball had a 60-game season in 2020, nobody really questioned whether there needed to be asterisks included with the records.”

As Thorn points out, the National League had 60-game seasons in both 1877 and '78. So there is further historical precedent to justify using that many games as an acceptable minimum. The current standard for qualifying for the batting title is 3.1 plate appearances times the number of team games scheduled. For the ERA title, it’s one inning pitched per game scheduled. Using a 60-game minimum as a guide for single-season leaders, that’s a minimum of 186 plate appearances and 60 innings.

“This will knock out some of the more preposterous season leaders,” Thorn says. “It doesn’t mean their records are going to be changed. But in terms of creating a list of seasonal leaders for all of Major League Baseball history, including the Negro Leagues, we would have to put in some minimum standard.”

Then, of course, there’s the question of which games ought to count as Major League games in the first place.

That’s not a straightforward discussion. As a product of those segregated times, Negro Leagues seasons were a scattered collection of games that included barnstorming contests (including against players from National and American League teams), All-Star games, exhibition doubleheaders played in big league ballparks -- basically, anything to keep the business afloat.

Furthermore, the schedules within the leagues weren’t always honored. Many teams far out of the running were inclined to shut down rather than pay their players to merely play out the string.

Another issue is not knowing what we don’t know. Researchers are at the mercy not just of what was reported from those Negro Leagues seasons but what reports can even be unearthed all these decades later.

“There are instances where a game will be advertised in the newspaper: ‘The Homestead Grays play the Kansas City Monarchs next Friday!’” says Thress. “Friday’s paper will say, ‘They’re gonna play tonight!’ Then you find Saturday’s paper, and they don’t mention the game at all.”

All this added to the difficulty of the committee’s work.

“It’s complicated because of the unfortunate state of the historical record, which, sadly, is never going to be complete,” Thress adds. “And also because of the fact that, in a sense, you’re interpreting something according to a standard we set now. But it’s not really the way the folks who played these games and organized them would see it. Everybody knows Josh Gibson was the greatest Black hitter and possibly the greatest hitter of his time, period. But whether he compiled an average that could be compared to Ty Cobb or Rogers Hornsby, I don’t think people thought about it that way. It didn’t occur to them to compare numbers between leagues.”

In compiling the Seamheads database, Ashwill was inclined to include stats from any games he considered to be Major League quality, including interleague games in the 1940s that did not count in the various Negro Leagues’ season standings.

“There are folks who say those games shouldn’t count,” Ashwill says. “But those are some of the most important games in the history of the Negro Leagues. They played these massive four-team doubleheaders in New York City, with the biggest crowds. It’s tough for me to think that those should be thrown out and not counted.”

Because some games were stripped from the record, the official database includes numbers that differ from what was previously publicly available on Baseball Reference and elsewhere.

The season and career stats for the Negro League players are inevitably incomplete, with researchers estimating that about 80% to 85% of the data has been uncovered. But that’s better than leaving these players out of the register altogether.

“It’s never too late,” Sean Gibson says. “We’re excited that things are moving forward.”

The process of going from the 2020 announcement of the Negro Leagues’ pending inclusion in the record book to the 2024 announcement of their actual inclusion was a long one. Thankfully, it was completed while Teasley, who went on to have a long and distinguished career as a coach and educator in the Detroit area, is still with us.

Ultimately, though, this process only made official what MLB had already acknowledged, what the researchers who have dedicated so much time to this project believed and what Teasley knows in his heart: Though his time with the New York Cubans was brief, Teasley was, in fact, a big leaguer who lived out his dream.

“I always felt,” he says, “that the Negro Leagues were my Major League.”