They had 1 career AB, 1 career hit. Nothing else.

A version of this story originally ran in 2019.

A player's first Major League hit is a special moment, often marked with a souvenir ball rolled into the dugout and cheers from the crowd.

For the stars, that hit is only the first of hundreds -- thousands, maybe -- in the big leagues. For players like that, the game is a series of tomorrows, each one a chance to repeat past fortunes or repair past flaws.

But for a select few, tomorrow never comes. Their path to the bigs is barbarous, and their leash is not long. Not even success can certify their survival.

In modern AL/NL history, 154 position players finished their professional careers with just one plate appearance in the Major Leagues, their careers distilled down to a single stint or, in the famous case of Eddie Gaedel, a single stunt.

Of those 154, just 16 ripped a hit.

Of those 16, only five are living.

They are baseball’s one-hit wonders. One walk from the on-deck circle to the batter’s box. One trip down the first-base line. One story to tell.

These are their stories.

* * * * *

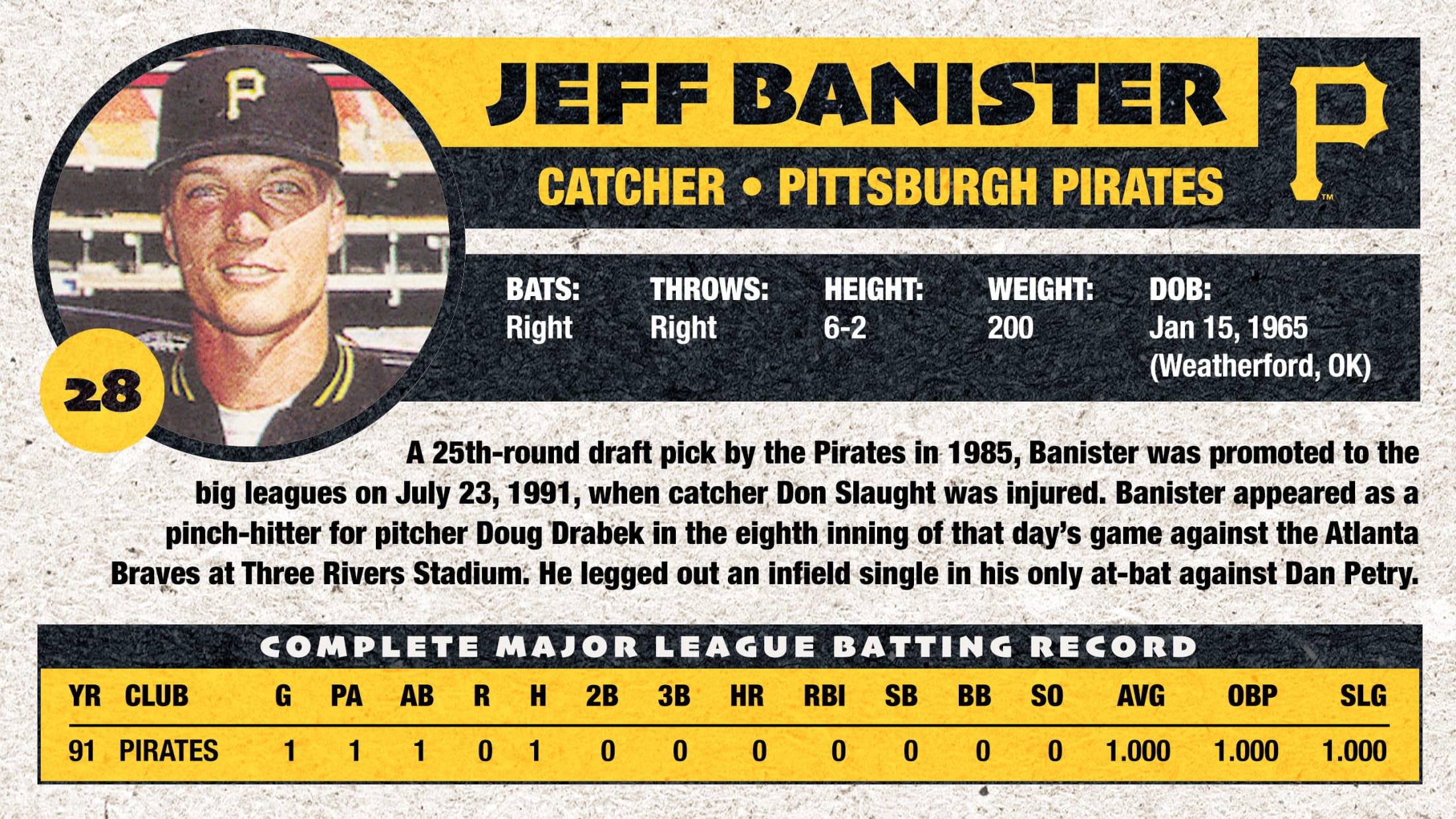

Back in Spring Training of 1991, with his wife, Karen, marooned in La Porte, Texas, at the house they had just bought and could barely afford,

With Jeff making Minor League money, Karen on a teacher’s salary and mortgage payments eating up any potential travel spending, this marriage would be a long-distance relationship for the duration of the 1991 season.

Unless …

“If I make it to the big leagues by July 23,” Banister had told his bride, circling the date on that bantam Bucco docket, “you know where the Pirates are coming right after that? Houston.”

They both laughed at the fantasy. Banister, a catcher, was blocked by Mike LaValliere and Don Slaught. Still, he tucked that schedule into his wallet, never thinking much of it until July 22, around 11:30 p.m., when his Triple-A Buffalo manager, Terry Collins (yes, that Terry Collins), called him with the news that he was getting promoted to fill the roster spot of the injured Slaught.

Banister’s idea hadn’t been so crazy, after all.

Then again, for Banister to be playing baseball at all was pretty crazy, too.

When he was 16 and a sophomore at La Marque (Texas) High School in 1981, doctors discovered that his slow-to-heal ankle injury was actually bone cancer. An infection had spread to his knee, and Dr. Lee Roy Lockhart recommended amputation of the lower half of his left leg.

“You’re not taking my leg,” Banister told the doc. “I’ve got big league baseball to play.”

Lockhart wasn’t so sure. But the seven surgeries he performed on Banister between January and July of 1981 saved the leg.

Probably my favorite part of the day is when I get up in the morning and put my feet on the floor. Because there were a couple of different times when I was told that would never happen. My legs were the two things that I was either not going to have or were not going to work anymore, and those two things carried me down the line to first base to etch a moment in time.

Jeff Banister

That was the first time Banister’s baseball career came back from the dead. The second was after what happened at Lee College in 1983. Banister moved up the third-base line to catch a throw toward the plate. When the runner tried to leap over Banister, the runner’s knee hit him square in the head. Banister’s body went numb. The trauma to his spinal cord and column paralyzed him for a week and a half, and his hospital stay stretched on for the better part of six months.

When he was finally released, 75 pounds lighter than when he arrived, his doctor told him he would never play ball again. But by the following spring, he was not only back in uniform but back behind the plate, warnings, risks and sanity be damned.

The Pirates took Banister, who had transferred to the University of Houston, in the 25th round in '86, but, beyond some raw power, he didn’t have the tools to be a legit Major League prospect. By then, his broken body hurt like hell, and he was being groomed to coach.

Still, in ’91, with a roster spot in Triple-A and that Pirates schedule in his billfold, the dream of playing in Pittsburgh -- and Houston -- was still alive.

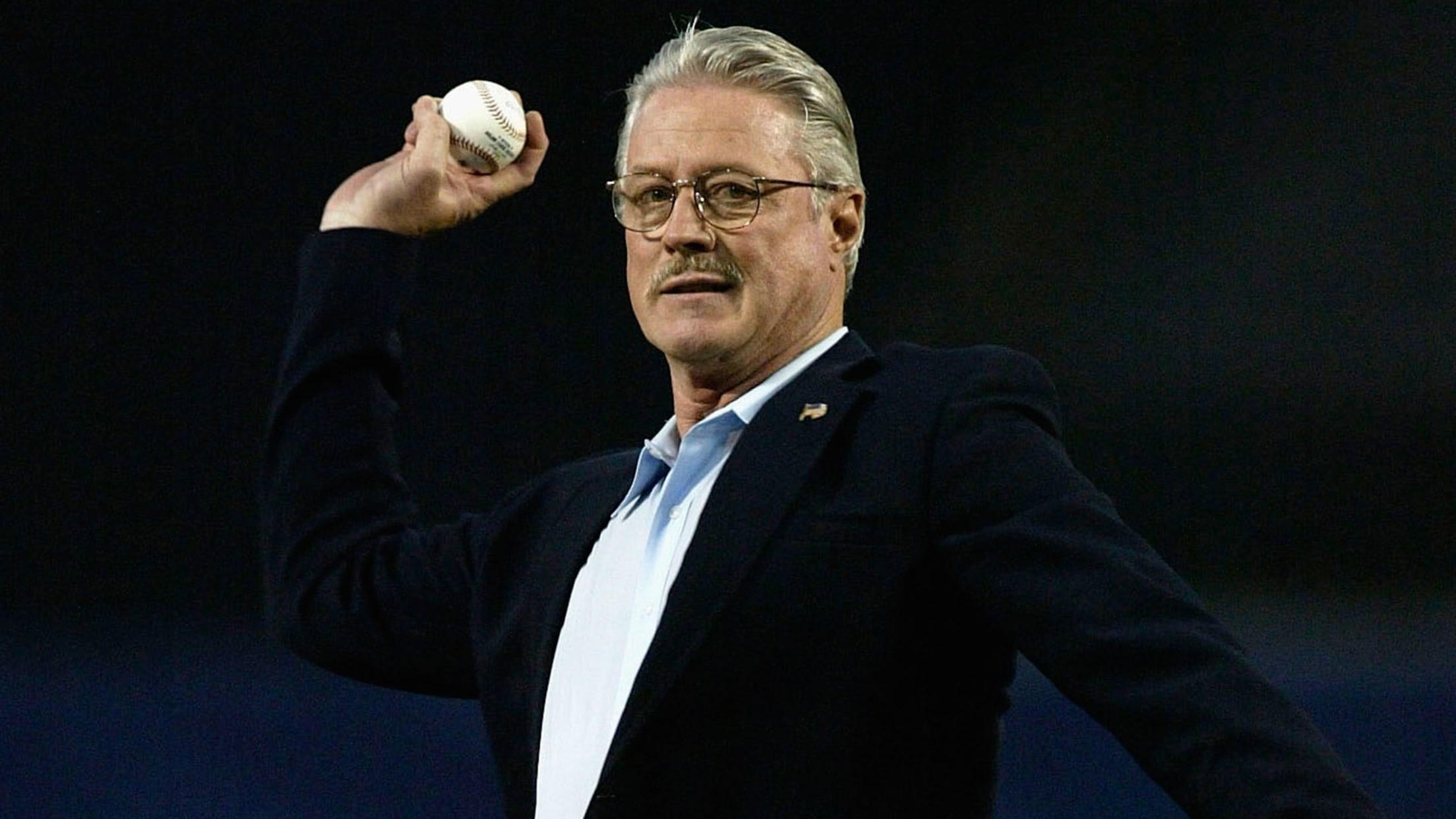

When the July 23 of preseason pipe dreams actually did arrive, Banister was sent up to pinch-hit for pitcher Doug Drabek in the seventh inning of a game against the Braves. He swung on the 1-1 pitch from Dan Petry and sent a hard grounder to the left-hand side. Shortstop Jeff Blauser fielded it on the run deep in the hole and made a leaping throw to first. But a hustling Banister beat the throw, using those legs saved by surgery and science.

“Think about that,” he later told MLB.com. “Probably my favorite part of the day is when I get up in the morning and put my feet on the floor. Because there were a couple of different times when I was told that would never happen. My legs were the two things that I was either not going to have or were not going to work anymore, and those two things carried me down the line to first base to etch a moment in time.”

Banister made it to Houston, as intended, and got to be with his wife on Thursday, July 25, an off-day for the Pirates. Meanwhile, his story of beating cancer and paralysis to get an at-bat in the big leagues received national attention. NBC’s “The Today Show” even scheduled an interview with Banister to take place from Houston the following Monday.

But Banister wouldn’t even be with the big league club by the time Monday rolled around. The Pirates made a series of transactions that weekend, including replacing Banister with Tom Prince, who was considered a more legitimate catching prospect.

That’s how you get stuck at 1-for-1. You’re king for a day, only to cede your throne to a Prince.

In the ensuing offseason, Banister blew out his elbow playing winter ball. He missed the '92 season, attempted a comeback in vain in ’93, and became a Minor League manager in ’94. When Banister became manager of the Texas Rangers in 2015, his story of passion and perseverance inspired others.

Now that he’s on the managerial back-burner, fired by the Rangers at the tail end of the 2018 season, he’s drawing on those traits again.

“We love the game, and the game doesn’t love you back,” said Banister, who would become the D-backs' bench coach in November of 2021. “We love the innocence of it all and the struggle, the challenge, the excitement, the celebration, the relationships. And that internal battle with yourself in the batter’s box, in the field, on the mound, drives us the most. For me, even at a young age of 15, I loved every second of that. I loved the long days, the summer, the heat, the thought of playing the game of baseball. And I used that love for mental strength. I knew if I could hang onto it, what I wished and willed would come true.”

For one at-bat, it did.

* * * * *

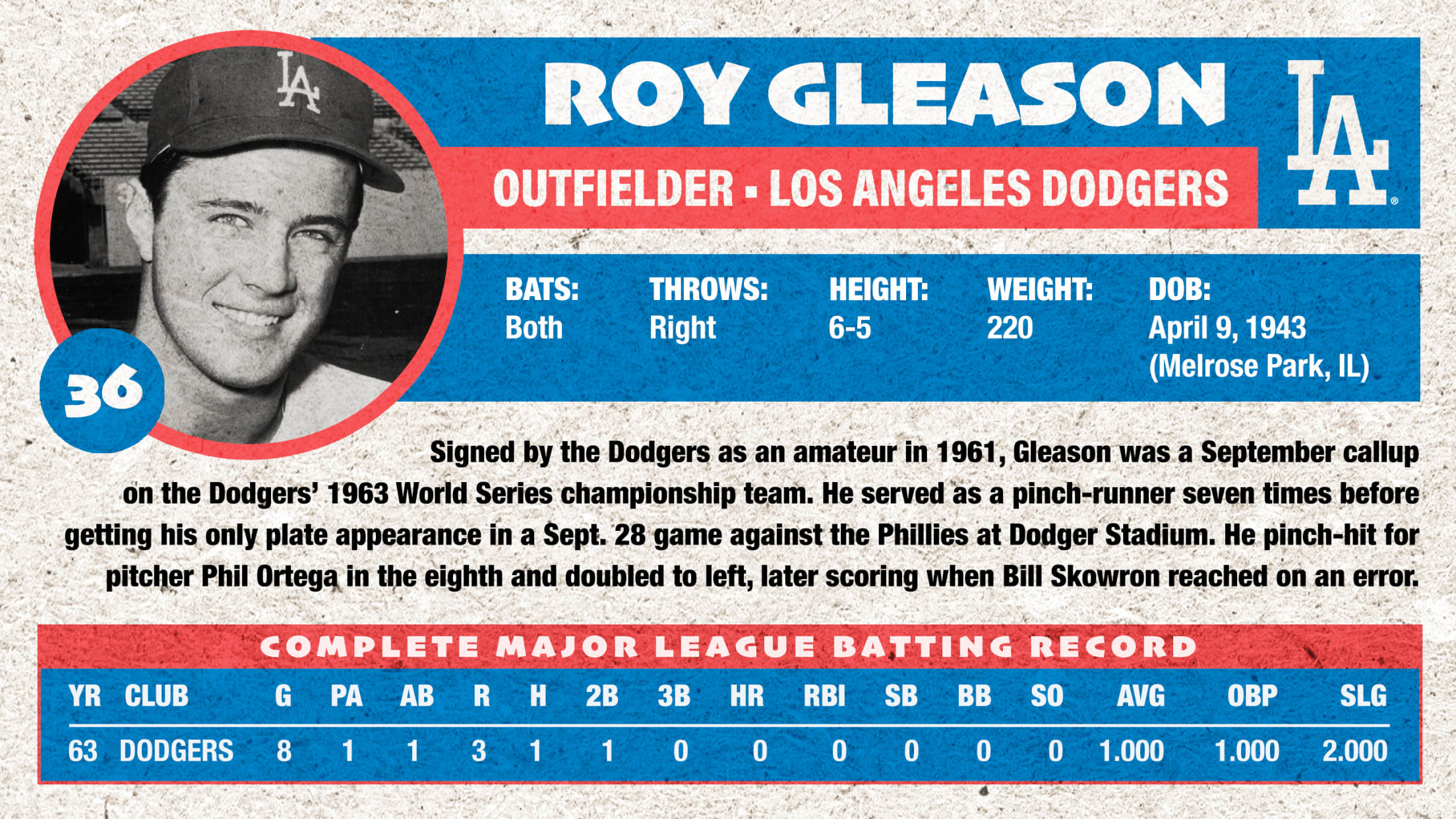

"Grab your gear, you’re going.”

But this time, one month into his stay at the Oakland Army Terminal in 1967, the words had a different weight.

At first, optimistically, Gleason, who was the sole supporter of his mother and sisters because his dad had abandoned the family years earlier, thought the paperwork he had filed to try to have his selective service classification changed from 1-A (available) to 3-A (deferred because of hardship to dependents) had been successful.

“I’m going home?” the 24-year-old Gleason asked the military police officer.

“No,” the MP replied. “You’re going to Vietnam.”

That’s how you get stuck at 1-for-1. You go to war.

I’m thankful for everything. Even Vietnam.

Roy Gleason

Gleason boarded the Flying Tiger Line out of Travis Air Force Base. He had been trained as an infantryman, but not even the swamp and heat of Fort Polk Army base in Louisiana could prepare him for what he’d encounter in the Mekong Delta.

“I was wondering -- and I’m sure every guy on that plane was wondering -- how many of us were going to fly home,” he recalled.

He arrived in Saigon on Dec. 20, 1967, with his 1963 World Series ring among the items he tucked into his foot locker. Gleason spent the entirety of what would be eight months in Vietnam in the field, in combat, and sheer survival earned him a rapid ascension in the ranks.

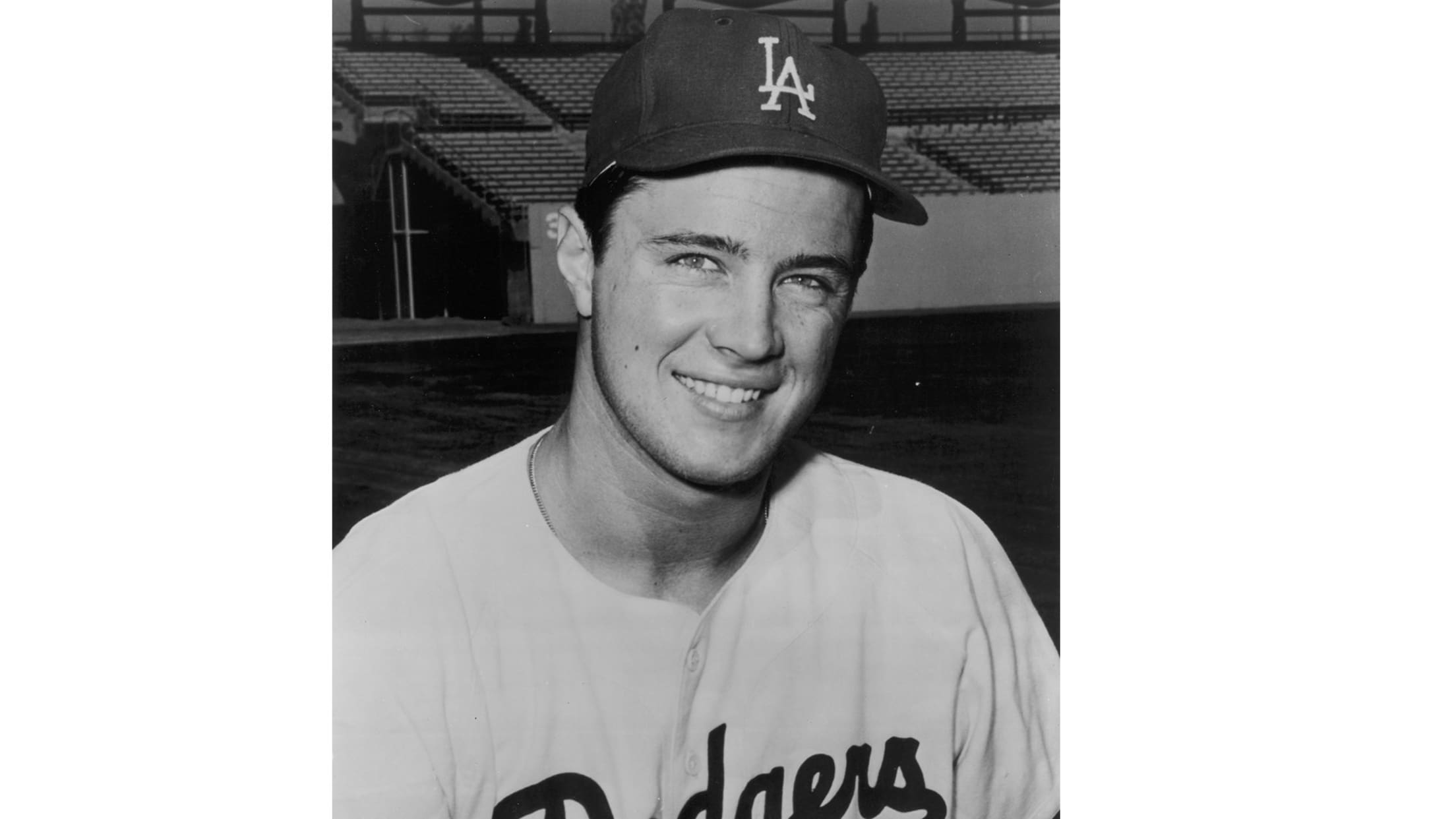

In baseball, Gleason had been accustomed to performance-based promotion. The 15 homers and 16 doubles he hit in 106 games at Class A Salem yielded a ticket to the bigs in September of '63, when he made seven appearances as a pinch-runner before getting a pinch-hit opportunity on the penultimate day of the regular season. The pennant was clinched and the game against the Phillies was out of hand by the time Gleason stepped in against Dennis Bennett in the eighth. He hit a liner to left, then hustled and slid in safely at second.

The first hit. The first of many, he thought, because Gleason was convinced he would be a superstar.

Alas, he didn’t get another promotion the next three seasons. In ’64, his manager at Double-A Albuquerque caught him dancing with a woman in a nightclub.

“I didn’t know it was his girlfriend,” Gleason said with a laugh, “until some of the other players told me.”

Conveniently, Gleason was sent back down to Salem the next day. He put up low numbers in the low Minors the rest of that year and in '65. But he made an adjustment late in ’66 that he thought would earn him another shot with the Dodgers in Spring Training of ‘67.

He didn’t get his shot that spring; he got his draft notice.

So instead of being a superstar, Gleason was a sergeant, promoted to that position within four months of his arrival in Vietnam. Because of this rank, he didn’t need to be the one walking point on July 24, 1968, during a sweep of a suspicious area near a small canal. But he opted to take the first -- and most exposed -- position in advancing through hostile territory.

The path looked worn, and Gleason had an uneasy feeling. He wanted to cross the canal and take a different route, but the commanding officer, in the rear of the group, ordered him to push forward to stay on schedule. Minutes later, Gleason walked under a tree, where one of the U.S. military’s own 155-millimeter rounds, repurposed into an IED, exploded. Instantly, the unit’s machine gunner, Anthony J. Sivo, was killed, and Gleason was struck by shrapnel in his left wrist and left calf. Blood soaked his pant leg and shot out of his wrist.

Later, laid up in a MASH unit, Gleason began asking himself the same question that hounds him to this day.

“Why didn’t I see that?” he said. “It’s something that stays with you all your life.”

He was in Saigon, awaiting transport back to the states, when a colonel pinned a Purple Heart to his pajamas -- an honor that felt more like failure. To add to the disappointment, Gleason received the contents of his foot locker, only to discover that his World Series ring was missing.

Still, home was home. When Gleason landed in California, he deboarded the medevac on a stretcher and asked to be lowered so that he could roll over and literally kiss the ground.

His baseball career never got back on track after that. After an early discharge from the Army, he began the ’69 season with Double-A Albuquerque. But he was so happy to be home that, he admits, he treated every night “like New Year’s Eve.” The Angels bought his contract for '70, and he was optioned to Triple-A Jalisco, where his tape-measure blasts earned him the nickname “Atomico” but didn’t earn him a callup.

The following offseason, he was doing roof construction to make ends meet. One day the driver of the work truck lost control of the vehicle over the side of a cliff. Gleason suffered a shoulder injury in the accident and never played another game.

The 78-year-old Gleason has done a lot of living since then. He tended bar at Don Drysdale’s restaurant, fell in and out of love, re-enlisted, found Jesus. He believes his faith is what saved him on May 8, 2017, when he was hit head-on by a speeding car on a two-lane highway by a driver who had swerved into the soft shoulder and overcorrected. The other driver was killed instantly, and the collision was so horrific that the California Highway Patrol officers who reached the scene couldn’t believe Gleason was still conscious. Though his car was totaled and his back wrenched, Gleason didn’t have a single broken bone.

So while he didn’t stick in the Majors, Gleason’s story is one of survival. In 2003, the Dodgers asked him to throw out a ceremonial first pitch and then surprised him with the presentation of a replacement for the ’63 World Series ring that had been lost -- or robbed -- overseas. He is the only person in the world with a Purple Heart, a World Series ring and a perfect Major League batting average.

“I’m thankful for everything,” he said. “Even Vietnam.”

* * * * *

The capital of New Hampshire is a town of about 43,000 people. Though Bob Tewksbury and Brian Sabean are products of Concord, it’s not as if the place is crawling with folks who had some kind of affiliation with big league baseball.

So people there know the story of how

But that doesn’t make him locally famous.

“More like infamous,” Tupman said.

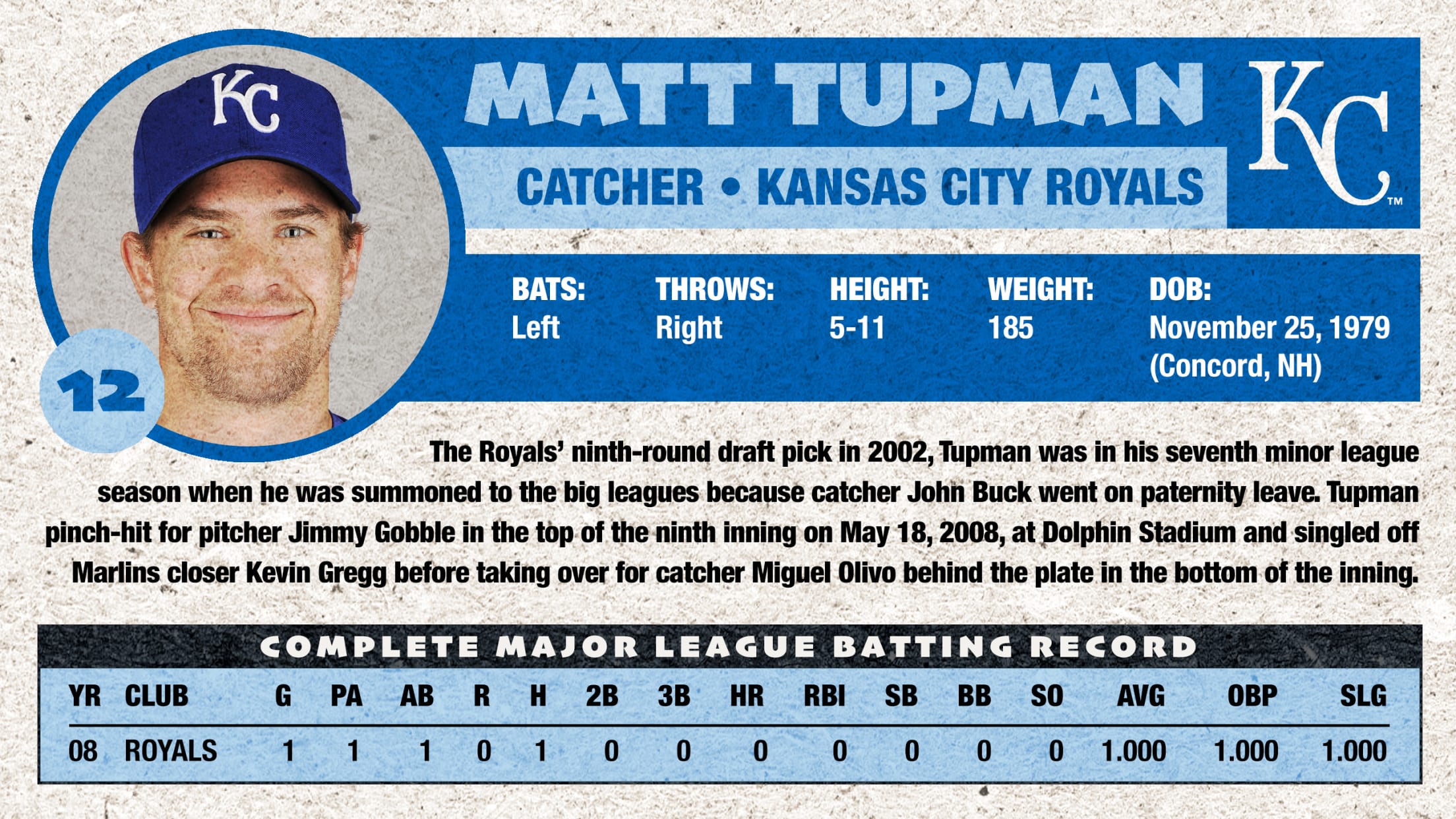

Four years of high school ball at Concord High. Three years of college ball at Plymouth State and UMass Lowell. Nine years of professional ball in the Royals’ and D-backs’ organizations.

One at-bat.

Tupman can’t say he’s satisfied with that equation. Sure, that at-bat was a blessing. And yes, there was sweet sentiment attached to standing at first base at Dolphin Stadium that May night in 2008 and thinking of his late father, Bill, a blue-collar baseball fan and Vietnam vet who had supported his son so passionately. To come from humble roots and ascend to that stage is special, and that’s not lost on Tupman.

But Tupman didn’t work his entire baseball life for one shot of special.

“It was like crack,” he said. “I wanted more. I wasn’t satisfied.”

It’s hard to be satisfied when you have to explain to the uninitiated why you didn’t make millions of dollars playing pro ball. And when you know -- and other people know -- that your own slip-ups contributed to your curtailed career.

So Tupman does not dwell on the experience. He became a personal trainer. All that’s left of his baseball career are a couple of Rubbermaid containers of memorabilia to pass on to his daughters, Gwen and Pippa. His only connection to the game is the 14-and-under travel team he coaches, and, even there, he’s more interested in teaching fundamentals than uncovering the next big leaguer from New Hampshire.

But if you want to hear the story? Sure, he’ll tell you the story.

The Royals drafted Tupman in the ninth round in 2002. Though he had no visions of All-Stardom, he was certain he could make it as a big league backup. He didn’t hit for power, but he got on base at a good clip (including a .425 OBP at the Double-A level in 2006) at a time when that skill was increasingly valued. He was ranked by Baseball America as the organization’s best defensive catcher multiple years.

But Tupman couldn’t get so much as a September callup to Kansas City from Triple-A in ’06 or ’07. And even when he took the vacant roster spot of a suspended Miguel Olivo at the outset of ’08, manager Trey Hillman didn’t give him an opportunity in the four days he was on the active roster.

I had that New England attitude. I ran my mouth probably when I shouldn’t have a few times.

Matt Tupman

“It came down to a popularity game,” Tupman said. “I had that New England attitude. I ran my mouth probably when I shouldn’t have a few times. … I was a fiery little player. And I think it was my inability to keep my mouth shut that worked against me. I think they just straight-up didn’t like me.”

A month into the ’08 season, John Buck’s wife prematurely gave birth to twins. Tupman was summoned again. And again, he rode the bench. But on May 18 -- a getaway day in Miami, with the Royals up 9-3 in the ninth -- Olivo and outfielder Jose Guillen, who had played with Tupman in winter ball, put a plan into action.

“Olivo faked that he was dehydrated,” Tupman said. “And Josey, being a leader on the team, went up to Hillman and said, ‘You’ve got to give the kid an at-bat.’ My relationship with Josey got me one chance.”

Facing Marlins closer Kevin Gregg, Tupman got a hanging splitter on a 1-0 pitch and lined it to right field.

“And they’ll save that baseball, as Hanley Ramirez and third baseman [Jorge] Cantu give it over to [third-base coach] Luis Silverio,” Steve Stewart said on the Royals’ broadcast. “They’ll toss it over to the Royals’ dugout, and there’s a keepsake for Matt Tupman. A very special day for him.”

He has the ball. He has the DVD. He has his story to tell.

But that’s all Tupman has. And his disappointment over how it all went down -- and how it ended -- is evident.

After his hit, the Royals let him make the trip to his native New England, where he watched Jon Lester no-hit his teammates at Fenway Park on May 19. Then they sent him down for good.

The following season, Tupman asked for and received his release midseason after a clubhouse blowup in which he had angered manager Mike Jirschele by begging out of the lineup with a bad sinus infection. The D-backs picked him up for the remainder of the year. But when Tupman, a free agent, tested positive for marijuana use while playing winter ball in the Dominican Republic, the ensuing 50-game suspension effectively ended his time in organized ball.

That’s how you get stuck at 1-for-1. Politics, pugnaciousness and pot.

“It’s a tough pill to swallow,” Tupman said, “when you know you were good enough to play and it ended with choices you made.”

The frustration followed Tupman. Nine years of pro ball. One at-bat.

Not enough.

* * * * *

His day typically begins at 3:30 a.m., ends at 10 p.m., and in between are the treks up, down and around the Southern California streets and freeways. The territory he supervises extends from Ventura, northwest of Los Angeles, down to the Mexico border. The work of installing and maintaining highway lighting and city traffic signals and fiber-optic systems is physical, demanding and cutthroat.

When

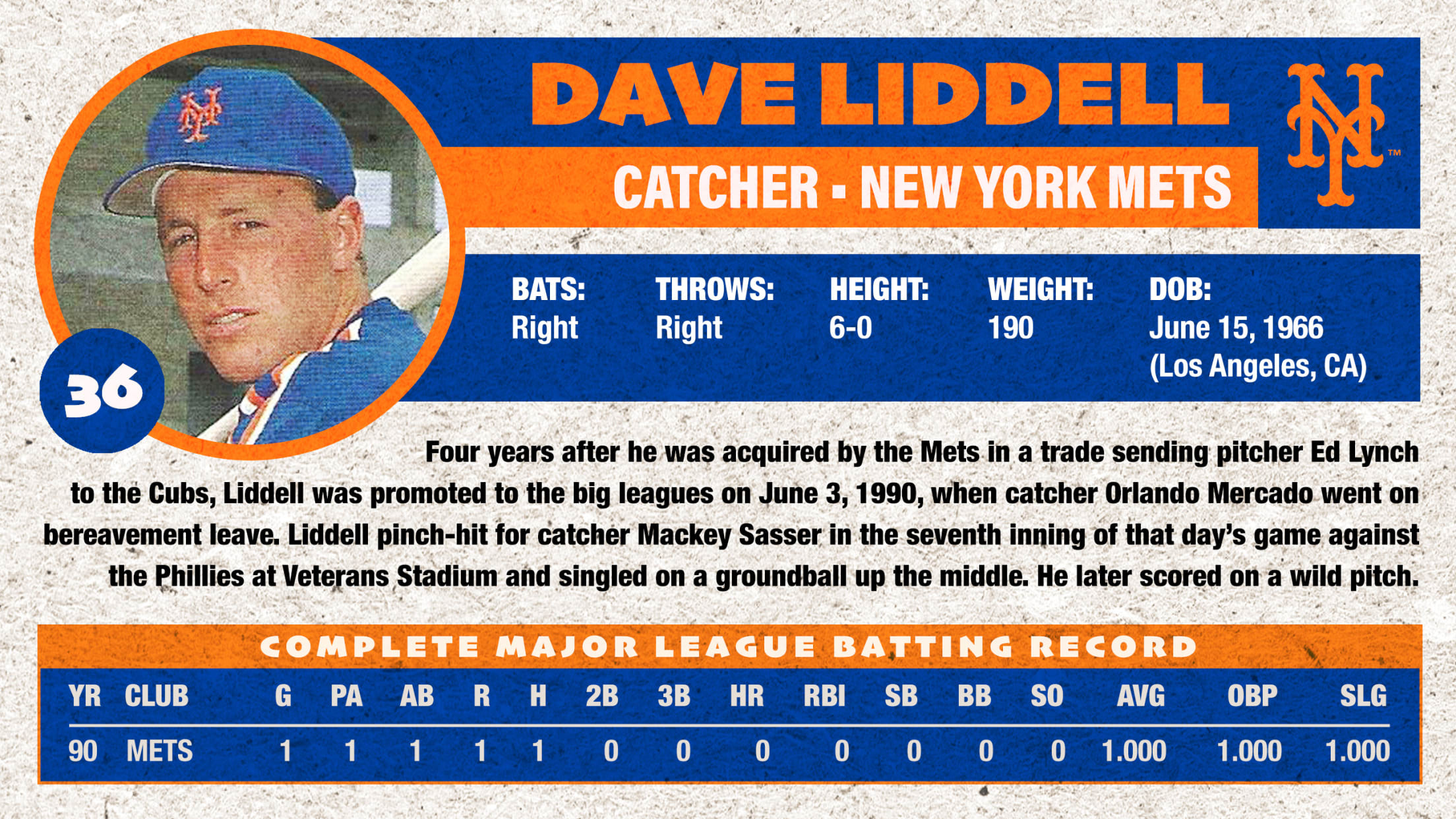

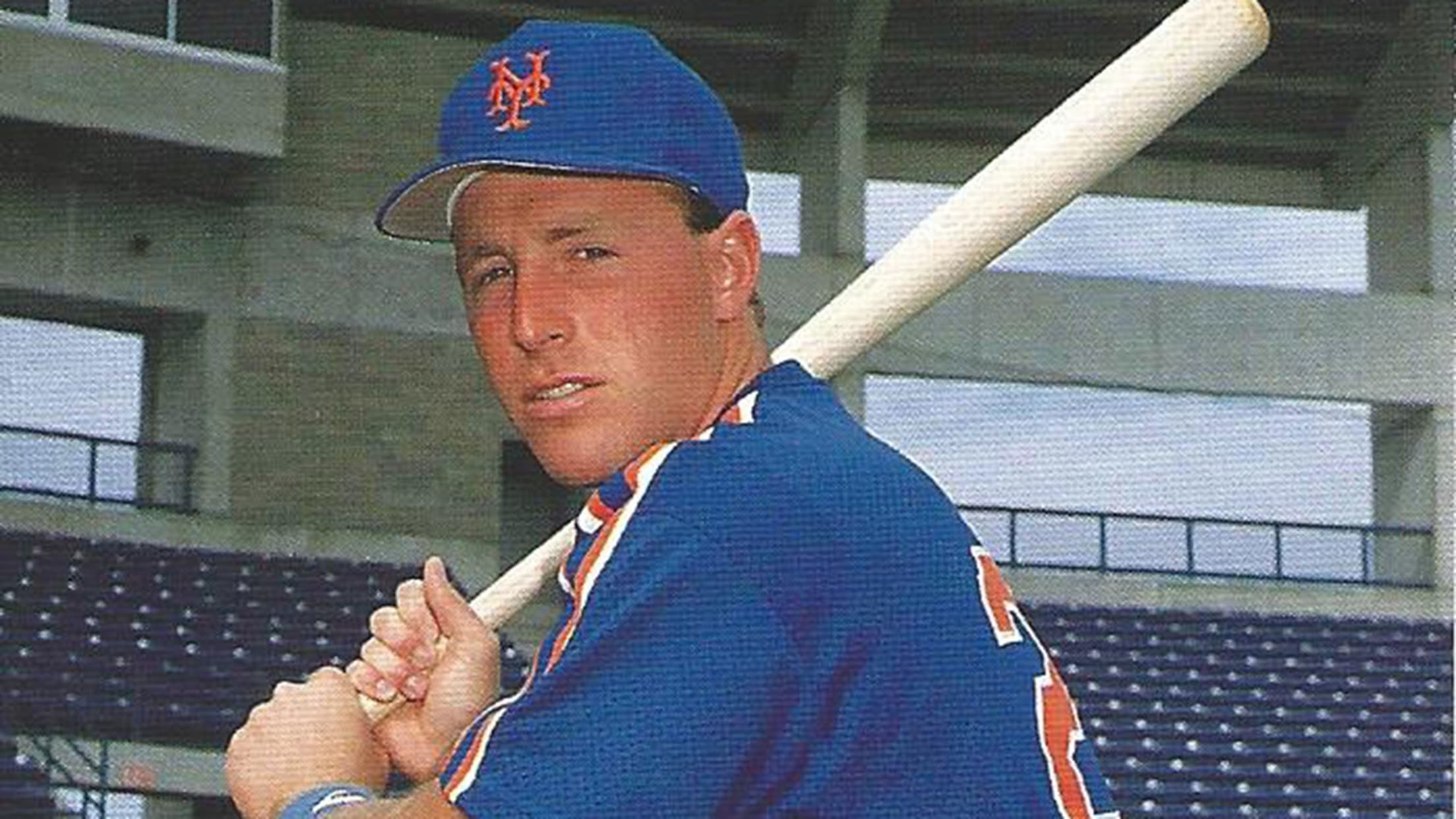

But such reflections are now infrequent for the 52-year-old Liddell. Many of the people he works with don’t know about his baseball past. He doesn’t announce it. He doesn’t elaborate on it. When baseball cards randomly arrive in the mail that fans want signed, he tosses them aside.

“I’m not a ballplayer,” he says. “I’ve put that part of my life in the closet.”

Because he spent nine seasons in professional baseball as a catcher in the farm systems of the Cubs, Mets, Brewers and Orioles, Liddell entered his current career later than most. When he left the brotherhood of baseball and joined the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, his bosses were his age. He had no education, no experience, no savings. But he had been indoctrinated to the idea that every time you go 0-for-4, every time you don’t hustle down the first-base line, every time you fail to throw out the opposing runner, you run the risk of somebody taking your job and yanking money out of your back pocket.

It's the one element of the baseball world that Liddell brought with him to the real world. And people in the real world don’t always understand the unusual intensity he brings to his role as an electrical division superintendent.

“They don’t know what competition is,” he says.

Liddell learned it the hard way, with a humbling baseball career in which he suited up for 12 different Minor League teams in four organizations and hit just .215.

Crack the laser-focused façade of present-day Liddell, and you’ll get great stories about the baseball-playing Liddell -- the Riverside, Calif., kid from a family of high school dropouts who got drafted by the Cubs in the fourth round in ’84 and signed for $31,000. You’ll hear how he roomed with Greg Maddux in rookie ball. How he got traded to the Mets after the Cubs drafted a better catching prospect in Joe Girardi. How he was nearly released in ’88, only to play himself back into the good graces of the Mets’ front office and earn an invite to big league Spring Training camp in ’89. He ended up splitting that season between Double-A Jackson and Triple-A Tidewater.

What we’re here to talk about, though, is the hit. It came in '90, in the midst of an otherwise miserable year at Tidewater, at a time when Liddell’s belief in his abilities had been all but destroyed by the quality of the competition. He was sitting sullenly at his locker in the visitor’s clubhouse in Louisville one day, wondering, seven years into his pro career, if he would ever learn how to hit, when his manager, Steve Swisher (yes, that Steve Swisher, Nick’s father), tapped him on the shoulder.

“I’m getting sent down to Double-A, right?” Liddell recalls saying.

“No,” Swisher replied, “things are happening. You’re getting called up.”

He could have thrown that first pitch at my head, and I would have swung at it.

Dave Liddell

Mets catcher Orlando Mercado’s father had passed away, and the team needed a backup while he was away. Just like that, Liddell was on a flight to Philly, where the Mets were playing. Upon arrival, he hopped in a cab, told the driver, “Veterans Stadium, boss!” and was on his way.

It was a Sunday afternoon, June 3. Mackey Sasser started behind the plate, and Pat Combs was twirling a one-hitter for the Phillies through seven, with the Mets trailing 8-1. Davey Johnson let Liddell pinch-hit for Sasser to open the eighth.

“He could have thrown that first pitch at my head,” says Liddell, “and I would have swung at it.”

That first pitch was a fastball running away from the plate. Liddell hit a hard ground ball up the middle and through the hole.

“How about that?” Tim McCarver said on the Mets’ broadcast. “The Mets enter the eighth inning with one hit, and it took a young man who was batting .178 in Jackson to get his first Major League hit.”

Liddell had never seen that clip until the reporting of this story.

“That’s bull----!” he said, watching it. “I was batting .178 in Tidewater!"

Liddell nearly got another opportunity the next night against Montreal. He was on deck to pinch-hit when the game ended.

“That would have really screwed up my career average,” he jokes.

When Mercado came back, Liddell’s time ended. He spent the rest of that season at Tidewater. He played in the Double-A and Triple-A levels with the Brewers the next two years, then promised himself that if nobody called him by June 1 of ’93, he was done.

Nobody called.

That’s how you get stuck at 1-for-1. You run out of talent, and the phone stops ringing.

“To say the adjustment is hard would be an understatement,” he says. “There’s that shock of going from ‘I am somebody’ to … not so much.”

He’s proud of what he’s put together since then. He carved out an exhausting but lucrative career, met and married his wife, Jennifer, and created a life outside of baseball, with no regrets about his playing career.

“Realistically, I was barely over .200 as a Minor League hitter,” he says. “I got called up because of the death of another player’s father. It’s not like I earned it. The game owed me nothing. I never dwelled on it, because a man has got to make a living.”

And every morning, when the alarm goes off at 3:30 a.m., that’s what he does.

* * * * *

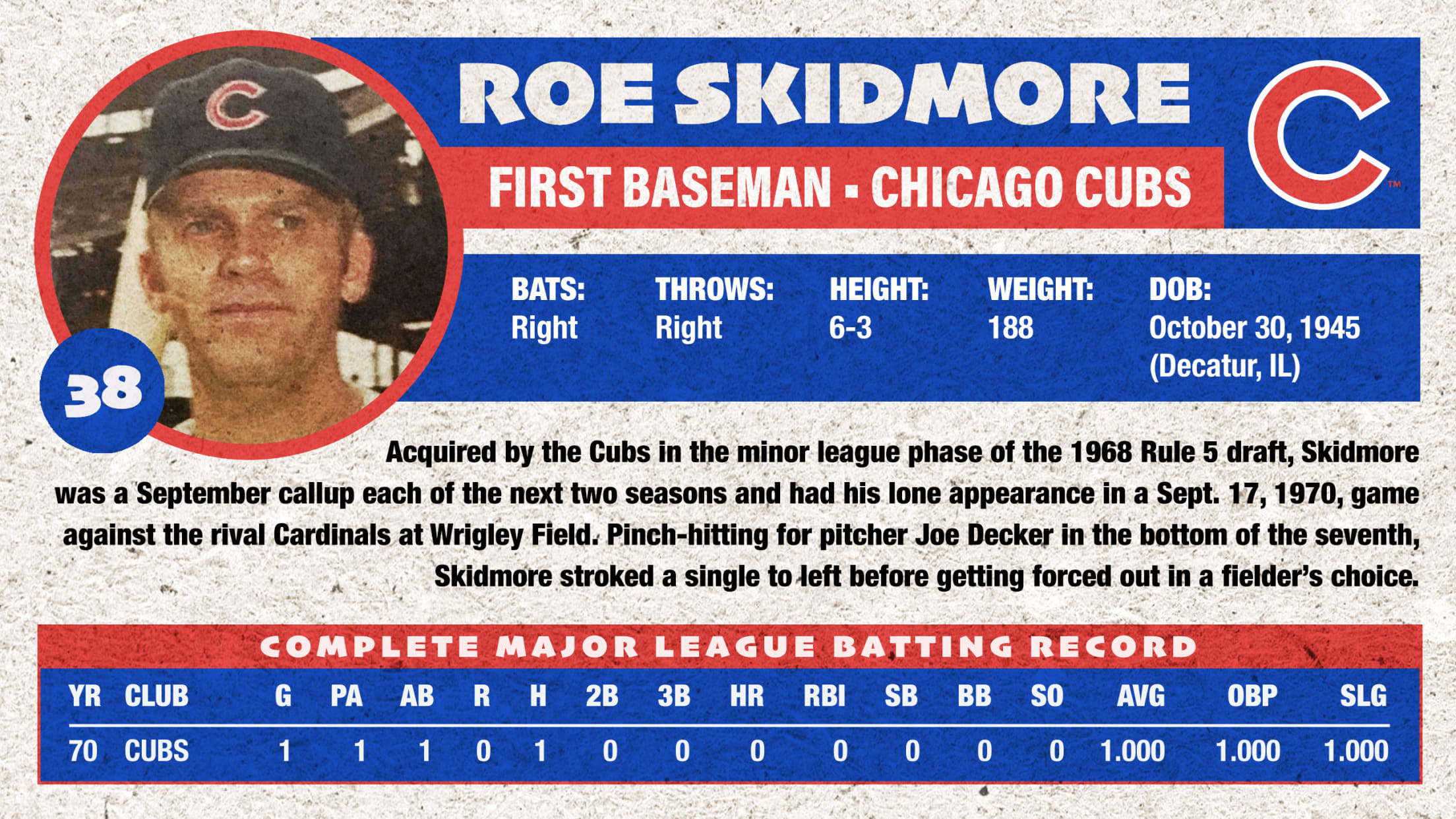

In the back room of Raupp’s Shoes in Decatur, Ill., the radio was tuned to the Cubs game. When

This day was different. Because just as Skidmore crossed the threshold of the door, he heard a name -- his own name, the one he had passed down to his son -- announced as the next batter.

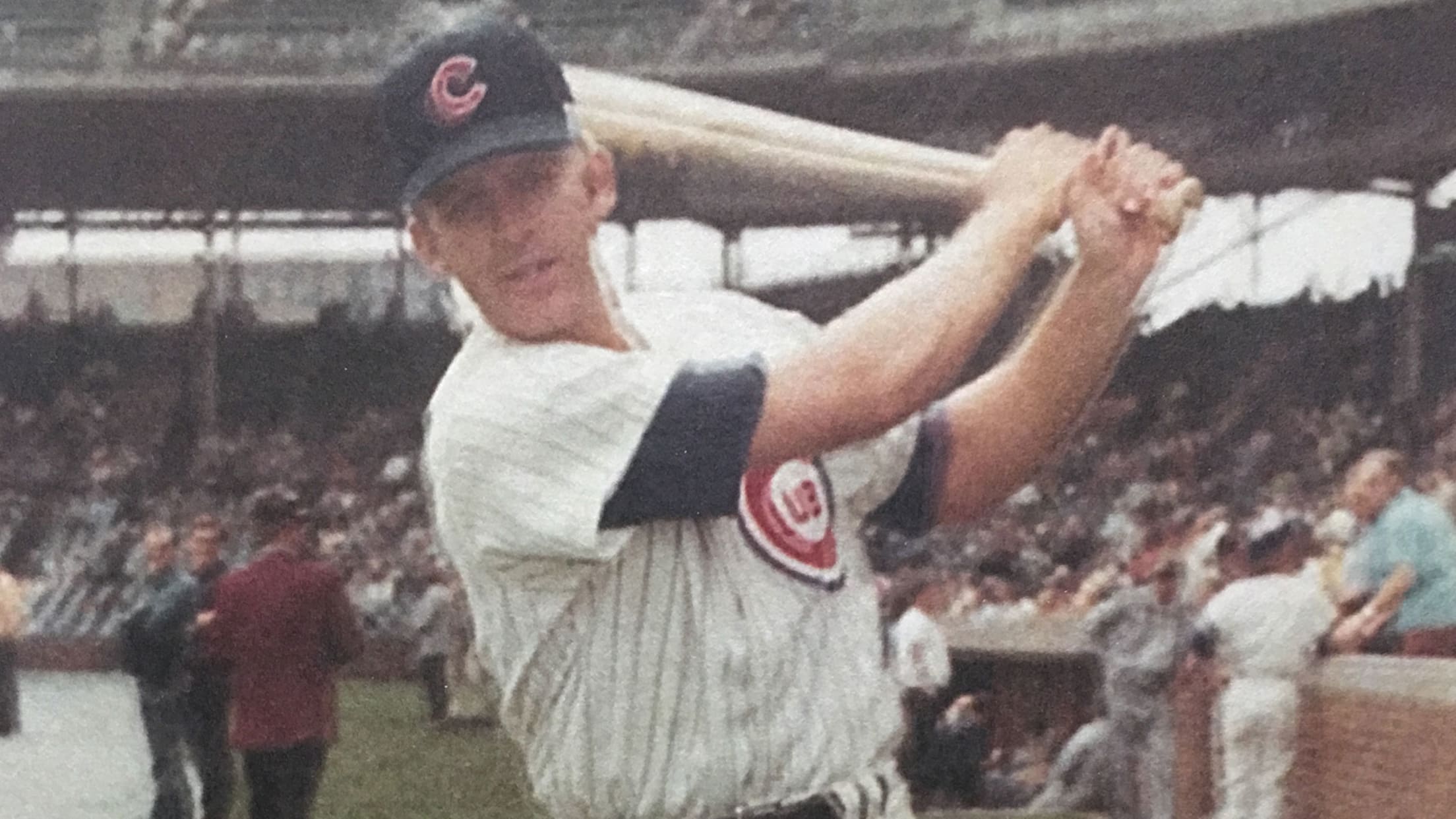

One hundred eighty miles away, at a rainy Wrigley Field, the younger Roe Skidmore stepped into the box in dazed disbelief, clutching the bat of a teammate because, in that frantic rush to the on-deck circle after he was surprisingly summoned as a pinch-hitter by manager Leo Durocher, he couldn’t find his own.

Though Skidmore had grown up in Decatur, almost equidistant between the Cubs and Cardinals, his dad had always made clear who the “home” team was. The Skidmore house had two radios -- one tuned to the Cubs’ broadcast to root for them, and one tuned to the Cardinals’ broadcast to root against them.

So to be in that batter’s box, wearing a Cubbie uniform in a game against the rival Cards, was a dream come true for the 24-year-old first baseman, even if the Cubs were getting crushed, 8-1. Skidmore had no way of knowing that happenstance had his dad listening in, nor did he have any way of knowing this amazing alignment of moment and opponent was the last gift big league baseball would grant him.

All he knew is that the Cardinals’ pitcher, Jerry Reuss, was familiar to him from the Minor Leagues, and that was better than having to stand in against Bob Gibson.

“He threw me a breaking ball,” the now-73-year-old Skidmore recalls, “and I hit a line drive right on the nose to left field. It went over Joe Torre’s head, Lou Brock fielded the ball, and he threw to Dal Maxvill at second base.

“When you only do it once, you remember all the faces involved.”

His journey to that sole single began at Decatur’s Millikin University. Because a handful of scouts lived in Decatur to keep tabs on the town’s Minor League club, it wasn’t difficult to get noticed. The Braves selected Skidmore in the 47th round of the 1966 amateur Draft, and Al Unser, a former big league catcher who inhabited the area, offered him $2,500 to sign.

“I don’t have the money now,” a confused Skidmore responded, “but I’ll get it to you as soon as I can.”

Skidmore wound up getting released by the Braves, scooped up by the Giants and then claimed by the Cubs in the Minor League phase of the Rule 5 Draft preceding the 1969 season. Come September of ’69, on the heels of a strong summer in which he hit .270 with 27 homers in Triple-A, Skidmore was brought up to the big leagues.

And sent directly to the bench.

When you only do it once, you remember all the faces involved.

Roe Skidmore

“I had a really good view watching the Cubs go down the drain,” he says of that infamous ’69 slide, remembered most for a black cat that crossed the Cubs’ path during a pivotal doubleheader sweep at the hands of the Mets on Friday the 13th. “If you pull up the black cat incident, look right in the middle of the guys sitting in the dugout, I was right there. That’s my claim to fame … other than the hit.”

The hit wouldn’t come for another year, when the Cubs made him a September callup again and Durocher finally threw the kid a bone on that lost afternoon of Sept. 17, 1970.

“I was scared to death,” Skidmore says, “and I don’t mind saying it.”

Skidmore swatted his single, was replaced in the lineup the next half inning by reliever Jim Dunegan, and didn’t get in another game. The Cubs, evidently not viewing him as an Ernie Banks replacement, shipped Skidmore to the White Sox in the ensuing offseason, and any hope he had of perhaps taking over first base for the South Siders after a strong 1971 season at Triple-A Tucson was thwarted when the Sox traded for Dick Allen.

That’s how it would be the rest of Skidmore’s career. He was behind Tony Perez on the organizational depth chart in Cincinnati, behind Torre and McCarver in St. Louis, behind Lee May and Bob Watson in Houston and behind Carl Yastrzemski in Boston.

That’s how you get stuck at 1-for-1. You get blocked by better ballplayers.

Skidmore finally packed it in after the ’75 season, at the age of 29 and with 1,171 professional games in the rearview. He went into the insurance business, where he worked for the next 32 years.

A jolly fellow with a sweet laugh, he doesn’t reflect on any of the above with disappointment.

“I’ve been accused of not taking a lot of things seriously enough,” he says with a chuckle, “but I never felt sour grapes. I kept thinking, ‘Well, daggonit, if I just have a good year, somebody’s going to get me, and I’ll get my shot.’ It just never came.”

As for the elder Roe Skidmore, he celebrated his 102nd birthday last July. That’s a lot of years and a lot of Cubs games.

And one hit that stood out above the rest.

* * * * *

What does it mean to go 1-for-1? Which element of the equation is worth fixating on -- the achievement of the dividend or the agony of the divisor?

The answer, it appears, is all relative to the expectations that preceded that lone plate appearance and the perspective life has provided in the years since.

Banister, for one, said he would love for the five one-hit wonders to somehow arrange to sign a bat for each other -- to laud, not lament, their place in an obscure baseball fraternity.

“That 1-for-1 will never be taken away,” he says. “However you judge it, I don’t care. Those who criticize never had that opportunity. We got to feel the joy of taking on the battle and succeeding.”