Baseball, more than any other sport, is defined by its numbers. After some 150 years, they've become sacred institutions, and they form their own shorthand language: 90 feet to first, batting .300, 100 RBIs, 500 home runs, 56 games with a hit.

The same holds true for uniforms. When you see the number two, you don't think "ah, the thing that comes after one" -- you think Derek Jeter. These are icons in and of themselves, inextricably intertwined with the legends they represented ... which is why it's so jarring to be confronted with the realization that a lot of those legends started out wearing a different number entirely. (Although you'd be forgiven for thinking that Willie Mays was just born with a No. 24 jersey on his back.)

We've presented baseball's strangest jersey sights below.

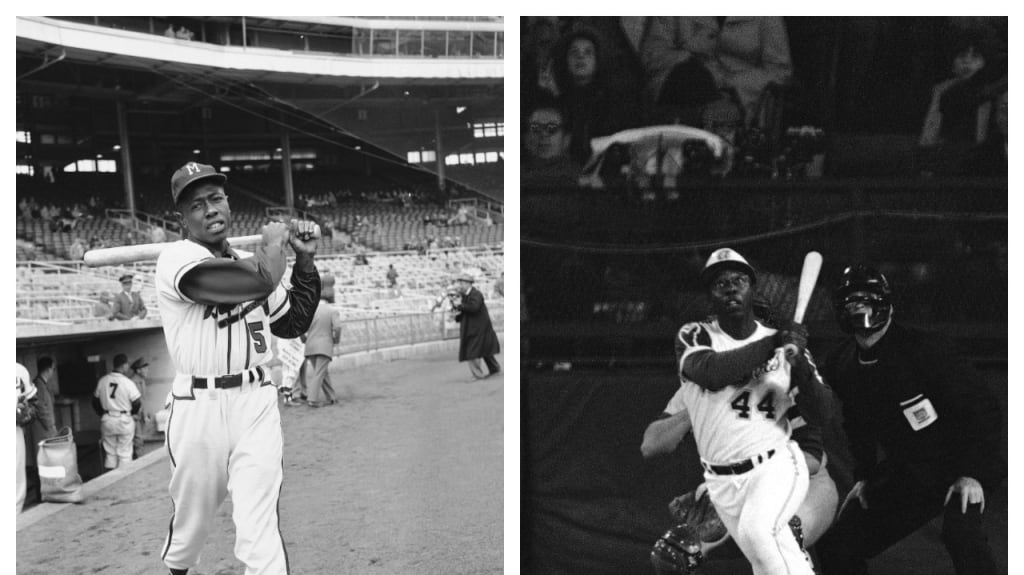

Hank Aaron, No. 5

Aaron has always been linked to the number 44. He hit 44 homers in a season four different times. He broke Babe Ruth's all-time home run record in the fourth inning of the fourth month of a year against a pitcher, Al Downing, who was wearing No. 44 for the Dodgers.

And, of course, it was what Hammerin' Hank himself donned for nearly the entirety of his iconic career ... save for 1954 -- his rookie year, when, after earning a spot on the Milwaukee Braves' Opening Day roster, the team's equipment manager told Aaron to stick with the number he'd been wearing all spring: No. 5. He finished fourth in NL Rookie of the Year voting with it, but switched to 44 in 1955 and never looked back.

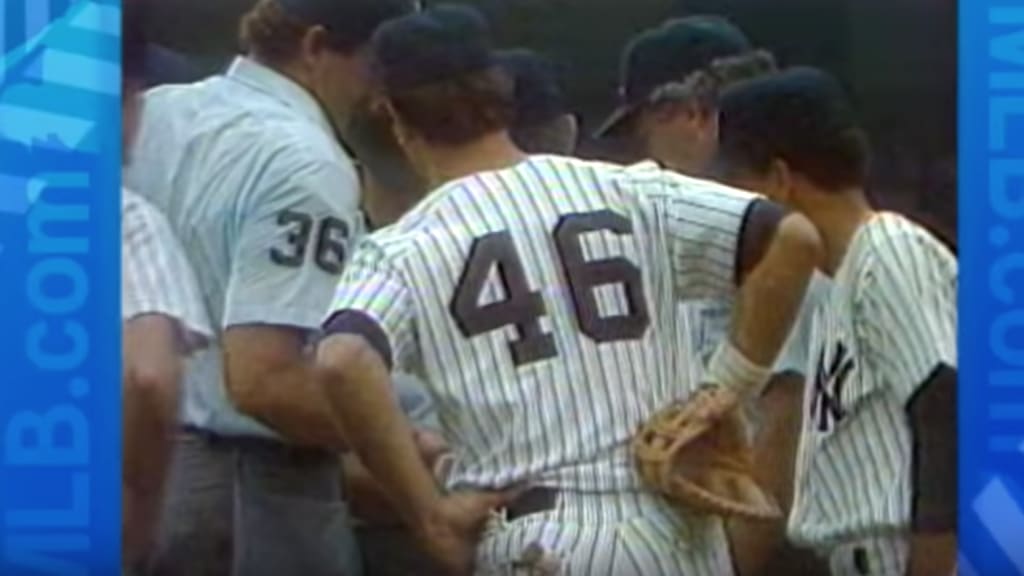

Don Mattingly, No. 46

No. 23 now hangs in Monument Park, one of 21 numbers retired by the Yankees. Before Donnie Baseball made it famous, though, he went by its double. Mattingly wore No. 46 during a cup of coffee in the Bronx in 1982 and his first full season in the Majors in 1983 -- including, famously, the Pine Tar Game. While Billy Martin was busy trolling George Brett, there was his first baseman:

He even wore it at the beginning of his breakout 1984 campaign, until he started hitting the cover off the ball and the team decided it should probably let its future captain have his pick of uniform numbers.

Clayton Kershaw, No. 54

Kershaw didn't even wear 54 for a full year -- he wore it for one start, the first of his career, at Dodger Stadium against the Cardinals back on May 25, 2008.

He only gave up two runs over six innings that day, but despite the solid debut, he had his heart set on No. 22 -- the number he'd worn growing up in Texas as a tribute to his hero, Giants and Rangers slugger Will Clark. There was just one problem: At the time, 22 was occupied by veteran Mark Sweeney.

Cue the game of numerical musical chairs. Sweeney had worn 21 for L.A., but lost it to pitcher Esteban Loaiza because he was late to re-sign heading into the '08 season. But Loaiza was designated for assignment just after Kershaw's debut, allowing Sweeney to slide down to 21 and give Kershaw 22 -- with a message for the lefty: “[Kershaw's] going to be in this uniform for a long, long time." Turned out pretty well.

Willie Mays, No. 14

It's become arguably the most iconic jersey number in baseball, if not all of sports, and it all started with Mays -- Rickey Henderson (and plenty of others) wore it because Mays had made it famous, Ken Griffey Jr. wore it because he loved Rickey Henderson, and today it's all over the place.

Before Mays was No. 24, he was No. 14 for his debut with the Giants on May 25, 1951, though photographic evidence remains hard to find. Jack Maguire wore 24 for New York at the time, but when the Pirates selected Maguire off wavers on May 28, the number became available.

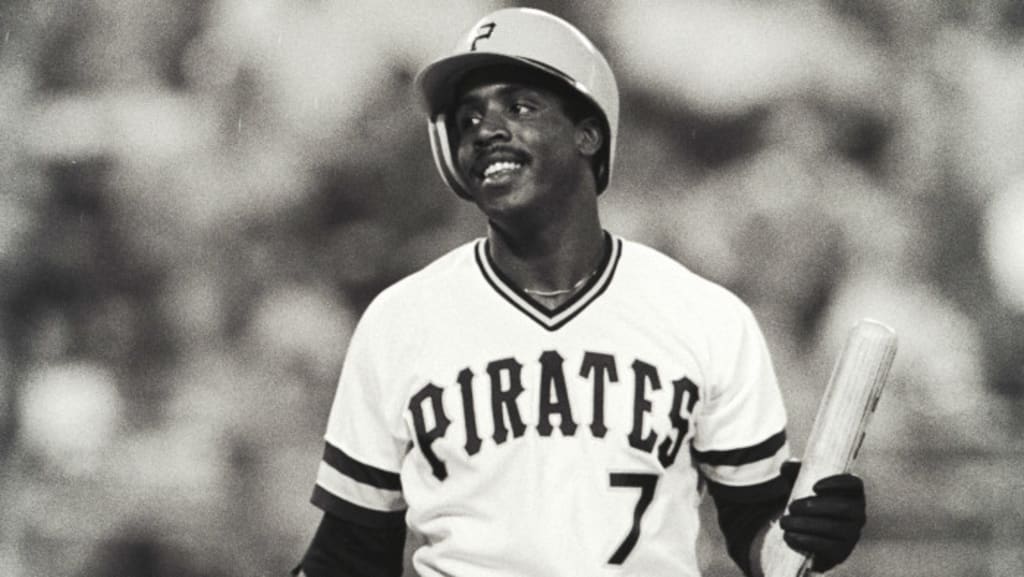

Barry Bonds, No. 7

Why not go from Mays to Mays' god-son? Bonds became a superstar in Pittsburgh as No. 24, a nod to his legendary godfather. He broke the all-time home run record in San Francisco as No. 25 (when he signed his record-breaking deal with the Giants in the winter of 1992, both Mays and the team were prepared to unretire 24 for him, but Bonds opted to go one higher in honor of his father Bobby, who'd worn 25 during his time by the Bay).

But for the first few games of his rookie season in 1986, he was No. 7, before making the switch later that summer.

Roberto Clemente, No. 13

Think about the mark that Clemente's No. 21 has made -- the right-field fence at PNC Park, standing 21 feet high; the stars who wore it in his honor, from Delgado to Sosa to Paul O'Neill -- and then give thanks to Earl Smith.

Smith's career lasted all of five games, but those five games just so happened to overlap with Clemente's debut with the Pirates in 1955. The 27-year-old had already claimed 21 (Clemente's preferred number because it matched the total letters in his full name, Roberto Clemente Walker), leaving Clemente to settle for No. 13. He only wore that number for a few days (briefly enough that photos of it hardly exist), when Smith was sent back to the Minor Leagues after recording just one hit in, you guessed it, 21 at-bats. Once No. 21 was freed up, Clemente made sure no one else ever donned it in Pittsburgh again.

Justin Verlander, No. 59

Verlander's worn No. 35 ever since his days as an ace at Old Dominion University -- a tribute to one of his heroes, Frank Thomas. (The Big Hurt went 1-for-10 against the righty, which seems awfully disrespectful.)

The lone exception? The first two starts of his Major League career, in the summer of 2005, when he had to more or less take what the team gave him on short notice ... and he wound up recording his first big-league strikeout wearing No. 59.

(Similarly, Félix Hernández also broke in with No. 59, before eventually settling in with 34 -- a nod to fellow Venezuelan and former Mariner Freddy Garcia.)

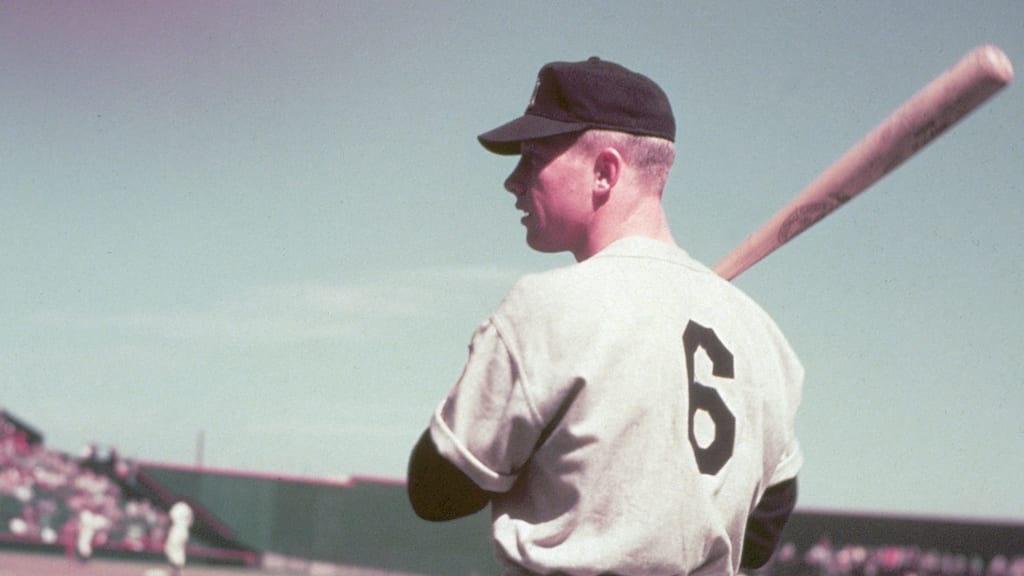

Mickey Mantle, No. 6

The Yankees brought Mantle to the big leagues in 1951, at just 19 years old, and he arrived with as much hype as anyone in baseball history -- "the greatest prospect I've seen in my time, and I go back quite a ways," as Bill Dickey said.

New York even assigned him the No. 6 jersey, placing him as the next in a line of icons from Ruth (No. 3) to Gehrig (No. 4) to DiMaggio (who spent his rookie year as No. 9 before immortalizing No. 5). So why do we remember him in a different number? Well, things didn't quite go as planned: He hit just .260/.341/.423 over his first 76 games, got sent down to Triple-A Kansas City in mid-July and continued to struggle. He was even on the verge of quitting, before a now-famous pep talk from his dad convinced him to stick with it.

Sure enough, the slump ended not long after -- but when Mantle returned to the big club in late August, third baseman Bobby Brown was wearing No. 6, so Mantle took No. 7.

Stan Musial, No. 19

On the contrary, Stan the Man is a player you only expect to see in a No. 6 uniform. And, for every competitive at-bat of his Cardinals career, he did -- from his debut in September of 1941 to his retirement in 1963. So how did this photograph come to be?

As it turns out, Musial wasn't the only player to don the 6 for the Cardinals in 1941 -- another promising young outfielder, Harry Walker, had as well, before being sent back to the Minors. When Walker returned to St. Louis camp the following spring, the team assigned him No. 6, leaving the younger Musial with No. 19. Walker and Musial both made the Opening Day roster, but the former was shifted to No. 10 following Hall of Famer Johnny Mize's departure, while Stan the Man grabbed No. 6 and never looked back.

Mike Piazza, No. 25

“Anything 3 is kind of my lucky number,” Piazza said on the day the Mets retired his No. 31 at Citi Field. When he first debuted with the Dodgers in 1992, however, the team gave him No. 25. Luckily, he wouldn't have to wait long: That winter, Bobby Ojeda left L.A. in free agency, freeing up his No. 17, which was snatched up by Roger McDowell -- he wanted it as a tribute to Ojeda, with whom he'd played on the Mets.

McDowell had previously worn No. 31, so when Piazza learned of the vacancy, he pounced.

Dustin Pedroia, No. 64

Surely Red Sox Nation will be thrilled to learn that, back during his days as an All-American shortstop at Arizona State, Dustin Pedroia wore No. 2 -- just like one of his heroes, Derek Jeter. Fortunately for all of us (but especially Xander Bogaerts), Boston gave him No. 64 when he first made it to the big leagues back in 2006.

By the time 2007 rolled around, he opted to go with 15, just in time for him to bag AL Rookie of the Year honors.

George Brett, No. 25

Royals fans probably know the story like the back of their hand: George Brett, face of the franchise, wore No. 5 as an homage to his very favorite third baseman, Brooks Robinson. He always wore No. 5. Heck, he is No. 5.

Except for his first two years in K.C., that is. When Brett first came up, he wore 25, and he would continue to through his first full season in 1974. He made the switch for good at the start of the 1975 campaign and never looked back -- save for a 1978 episode of "Fantasy Island," in which Brett for some reason appeared not in the number he'd made famous but in the number he hadn't worn for a good four years.

Yogi Berra, No. 38

By the time Berra was set to make his Yankees debut in 1946, the team already had him pegged as their catcher of the future. There was just one snag: Its catcher of the past and present was still around. At 39 years old, future Hall of Famer (and Berra's beloved mentor) Bill Dickey was wrapping up his final Major League season, and he had No. 8 locked down.

So Berra appeared as No. 38 at first, and then, in 1947, as No. 35 -- Aaron Robinson had won the catching job out of Spring Training, relegating Berra to the outfield.

By 1948, though, the job was Yogi's, as was the number. And when New York finally retired No. 8 in July of 1972, they honored Berra and Dickey together.

Chipper Jones, No. 16

This may be the rarest bird on the whole list, but we promise it's true: During his first stint with the Braves, an eight-game cup of coffee at the end of the 1993 season, Jones wore No. 16.

The reason? Journeyman catcher Greg Olson. “Chipper was just coming up at the end of the 1993 season and had worn the number all his life so I think he wanted it,’’ Olson told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. No rookie, not even a top overall Draft pick, can command his own number on day one, so 16 it was.

Olson was released in the winter of '93, though, and by the time Chipper came back from injury for his rookie season in 1995, the No. 10 was his.