Yankees Magazine: Closure

While touring the Hall of Fame, where his plaque will hang forever, Mariano Rivera reflected on his incredible baseball journey

As the traffic light at the corner of Main Street and Chestnut Street in Cooperstown, New York, turned from red to green and back again, the quiet intersection remained devoid of traffic for five, 10, 15 minutes. On this Thursday night in upstate New York where two couples were having dinner at the Cooperstown Diner, the only restaurant that had any semblance of a crowd was Mel’s at 22, a comfortable bistro located across the street, about a quarter-mile from the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The road separating the two establishments was flanked by snowbanks, icy sidewalks and a few restaurants, baseball card shops and souvenir stores. As the early evening turned to late night, the temperature dropped below zero. From the bar room of Mel’s at 22, the view of Main Street was not very illuminated. White Christmas lights adorning a few pine trees to the left of the street, and the lights that sat atop lampposts on either side of the street, broke up the otherwise dark backdrop.

On this same night, one of baseball’s brightest stars arrived in Cooperstown for the first time. Mariano Rivera, who had recently earned the sport’s first unanimous Hall of Fame selection, had pulled into the cozy village for a tour of the Hall’s vast museum the next day. In keeping with a long-standing tradition of each new inductee going on a guided tour at some point in the months between being elected and inducted, Rivera made the secretive midwinter voyage to Cooperstown just more than a week after being named on all 425 ballots.

For good reason -- only select Hall of Fame officials and an even smaller number of journalists knew of Rivera’s visit -- the quiet town remained almost as tranquil when the sun came up the next morning. As the sun came up on the first day of February, the busiest place in town was Schneider’s Bakery on Main Street. As local customers got their mornings started with homemade donuts, onion rolls and hot coffee, the smell of fresh-baked goods billowed into the 3-degree air outside.

***

At about 8:30 a.m., Rivera and his wife, Clara, arrived at the Hall of Fame. The couple was quickly escorted to the second floor of the museum, where they watched a short video about the history of the Hall of Fame. Following that, Erik Strohl, the Hall’s vice president of collections and exhibitions, began a tour that would last more than two hours. For Strohl, this marked the 32nd tour he would deliver to a new inductee, and right from the start, the curator and baseball aficionado’s storytelling expertise was evident.

The first room that Strohl brought Rivera into contained several artifacts from the 19th century, including some of the first protective gear ever worn by a catcher. As Strohl explained how an old-fashioned face mask was jokingly referred to as a “birdcage,” the previously reserved closer erupted in a laugh.

The tour then weaved its way to exhibits on some of the greatest players from the game’s earliest days, including one on Ty Cobb and another on Cy Young. When Strohl showed Rivera a glove worn by Young, the guide began to recite some of the stats that the starting pitcher racked up between 1890 and 1911, including Young’s 49 starts in 1892 -- which didn’t lead the league -- and his 511 career wins.

“He was the master,” Rivera said. “It’s as simple as that. He set the standard for every other pitcher who came after him.”

The tour got even more interesting for Rivera when the small group moved into a room dedicated to Babe Ruth. Among the most impressive items that Rivera was shown in that space were the bat that The Babe used to hit 28 of his record-setting 60 home runs in 1927, the baseball that he launched into the right-field bleachers at the old Yankee Stadium for home run No. 60 and a ticket stub from a game earlier that season.

“That’s not even the biggest bat The Babe used,” Rivera said as he got a closer look at the 36-inch, 38-ounce Louisville Slugger. “But you couldn’t use a bat like that in today’s game. You’d never get it around on the guys who are on the mound these days.”

A few minutes later, the group arrived at an exhibit titled “Pride and Passion, The African-American Baseball Experience.” When Rivera got to a glass display with a Brooklyn Dodgers No. 42 jersey worn by Jackie Robinson, he spoke about what it meant to be the last Major League player to wear the only number retired throughout the game.

“When you think about what Mr. Jackie Robinson went through when he first broke the color barrier, it moves you,” Rivera said. “I took the opportunity to wear his number seriously. I felt like I was representing the most important legacy in baseball every time I put that jersey on, and that was something that motivated me to be as good as I could be on and off the field. I was thankful to wear his number, and I’m honored to now join him in the Hall of Fame.”

After spending a few more minutes in that room, Strohl brought Rivera to a wooden bench situated in front of a life-size photo of the first Hall of Fame class from 1936. As Rivera sat down on the bench for a photo op, he was careful not to sit directly in front of one important player.

“I’m not blocking The Babe, right?” Rivera asked as he turned around. “He’s the most important person in this picture, and that includes me.”

After posing for a few photos, Rivera took a few seconds to admire the image on the wall of Ruth, Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson.

“These players are our patriarchs,” Rivera said. “They represent baseball for me. Knowing that they opened the doors, and that players like me were able to follow in their footsteps, is special. They’re the foundation of the game. I have so much gratitude for those players, and I’m proud to have played the same game as them. Looking at this photo, I’m just very thankful.”

The next stop on the tour was a red locker containing a pinstriped jersey that Lou Gehrig wore in his final season of 1939 and the trophy that was given to the Iron Horse by his Yankees teammates on the day he made his famous “Luckiest Man” speech at Yankee Stadium 80 years ago.

“That trophy was Gehrig’s favorite possession,” Strohl explained. “It meant so much to him, not only because it was given to him shortly after he was diagnosed with the terminal illness that would ultimately be named after him, but because his teammates gave it to him.”

In no rush to move along, Rivera bent down and read the poem inscribed on the trophy:

We’ve been to the wars together;

We took our foes as they came;

And always you were the leader;

And ever you played the game.

Idol of cheering millions,

Records are yours by sheaves;

Iron of frame they hailed you;

Decked you with laurel leaves.

But higher than that we hold you,

We who have known you best;

Knowing the way you came through

Every human test.

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting Friendship’s gleam

And all that we’ve left unspoken

Your Pals of the Yankee Team.

“That’s really beautiful,” Rivera said. “Knowing that the likes of Lou, Babe, Mickey [Mantle] and Yogi [Berra] wore the pinstripes made wearing that uniform special. I was lucky enough to have so many great moments on the field, but my greatest experience in baseball was just putting that pinstriped jersey on day in and day out. I thought about how special the players who wore that jersey before me were as I buttoned up my jersey before each game. I took my time and savored that experience every time I got dressed.”

Switching gears, the group walked to a large exhibit titled “¡Viva Baseball!” dedicated to Latin Americans who have shaped the game. There, Rivera began to reflect on the challenges that he faced during the first few seasons of his professional career.

“My first year was OK because I was in Tampa,” the Panama native said. “There were a lot of people there who spoke Spanish. But in my second year, I got promoted to Greensboro, (North Carolina), and it seemed like no one there spoke Spanish. That was really hard for me. It was frustrating to not be able to communicate with anyone, including my coaches. I would literally be crying when I was going to bed on so many nights.

“That experience pushed me to learn to speak English,” Rivera continued. “And, that’s when I felt that my career took off. Two of my teammates began teaching me English halfway through that summer, and by the end of the season, I could speak the language. I was the happiest guy in the world. People respected me on a totally different level, and I feel that it is so important for other Latin players to learn English.”

A little closer to home, Rivera gravitated to a display featuring artifacts from the career of Rod Carew, the first Panamanian player inducted into the Hall of Fame.

“He put us on the map,” Rivera said. “Rod was always our guy. He represented us in a great way, in a way that we can never forget. If it wasn’t for him, it would have been different.”

***

The group then made its way to the third floor, where a display on Major League ballparks was located.

“Besides Yankee Stadium, where did you like to pitch?” Strohl asked Rivera.

“Really, anywhere,” Rivera responded. “I really felt good in Seattle, Minnesota and Chicago, I guess.”

“Was there anywhere you didn’t feel good or lacked confidence?” Strohl responded.

“No,” Rivera said emphatically. “I felt like I could do well in any ballpark.”

The last stop on the third floor was a display of every World Series ring, situated in chronological order. Rivera admired many of the championship rings, especially those won by Yankees teams of the 1940s and ’50s.

“I’m proud to have five of those rings,” Rivera said. “But I don’t actually ever wear them. When I get my Hall of Fame ring, however, I’m going to wear it. That ring represents the pinnacle of baseball.”

As if the tour wasn’t impressive enough to that point, it would get even better.

“Let’s go downstairs to see a few special items,” Strohl said. “Items that are not on display.”

The group took an elevator to an underground level and walked into the temperature-controlled “collection storage” archive, which holds about 90 percent of the museum’s items.

Before the group arrived, Strohl had taken out about 20 items for Rivera to view and hold while wearing a pair of thin, white cotton gloves. As Rivera walked up to the table, situated in between floor-to-ceiling metal shelving units fully stocked with sealed boxes of priceless memorabilia, he smiled.

One of the first items that Strohl handed Rivera was the cap worn by Roberto Clemente under his batting helmet when he collected his 3,000th and final hit. The Latino pioneer and native of Puerto Rico passed away a few months later in a plane crash while delivering relief supplies to survivors of a 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua.

“This is really special,” Rivera said before requesting a photo with the historic artifact. “I was thinking about Roberto Clemente a lot today. He died while doing good for others, and that really characterizes what the Hall of Fame is all about.”

***

Among the other items that Rivera got to hold and pose with included a glove that Carew wore while playing for the Minnesota Twins, a baseball that Cardinals legend Bob Gibson threw during his 1968 MVP campaign and a Dodgers cap that fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax wore during his 1965 perfect game.

Strohl also took out a few items that were donated to the Hall by Rivera and other recent Yankees.

“This was the jacket Joe Torre wore during the 1999 World Series,” Strohl said as he pointed to the blue satin coat that the Hall of Fame manager made fans familiar with in the late ’90s and early 2000s. “When we got this jacket, we found a green stress ball in one of the pockets.”

“I guess that’s why Joe was so relaxed all the time,” Rivera joked.

When Strohl handed Rivera his own cap from the 2000 World Series, the closer’s tone became more serious.

“Those games were amazing,” Rivera said. “I remember (former Mets outfielder) Benny Agbayani going on the radio before that Series and saying that we were done and that the Mets were going to beat us. You never want to wake a sleeping giant, and that’s what he did.”

The last item that Rivera held was the bat that Ted Williams -- widely regarded as the game’s greatest pure hitter -- used to hit his 521st and final home run.

“I wish I could have faced Mr. Ted Williams,” Rivera said. “I would have liked to know what that would have been like. You want to face the best, and he was the absolute best.”

The tour ended in one of baseball’s most storied places, the Hall’s plaque gallery.

Upon entering the large open area -- featuring a marble floor and two rows of marble pillars flanked by the wood-paneled walls adorned with plaques of the men already inducted -- Rivera was escorted to Carew’s plaque and then to Robinson’s.

When he got to Robinson’s, the closer put his hand on it, and again praised the trailblazer.

“This man is a hero in every sense of the word, and he truly changed the game,” Rivera said. “I’m honored to be standing here.”

After stopping at a few more plaques, Strohl brought Rivera to the rotunda at the back of the gallery. They passed underneath a circular skylight partially covered in snow and then walked to the right. Strohl stopped Rivera.

“OK, Mariano,” the curator said. “Now, you’re going to see where your plaque will be placed.”

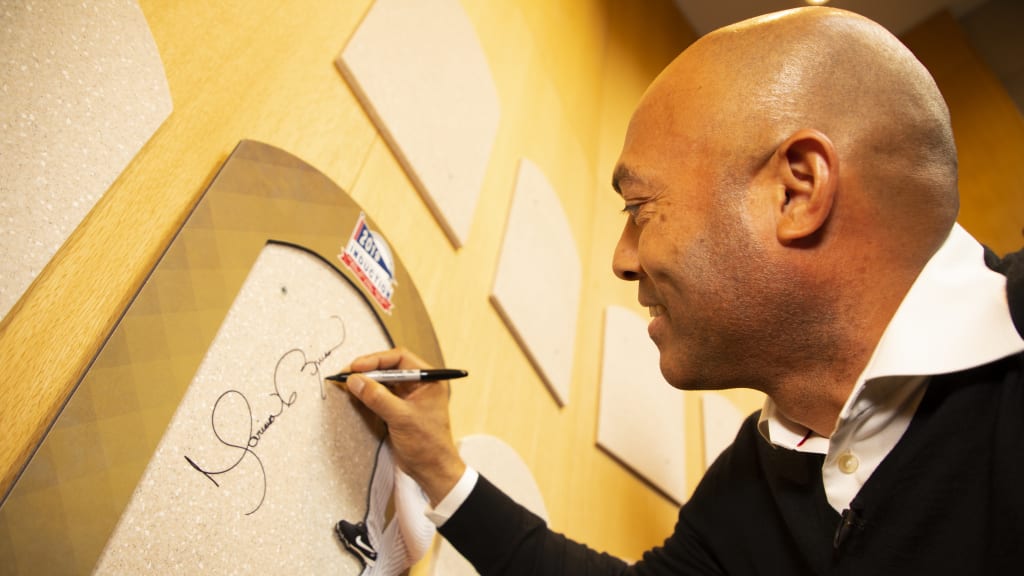

The group walked to a section of blank marble slates underneath a “2019” sign. For Rivera’s visit, his marble base had a decorative frame around it.

Rivera and his wife took a minute to admire the blank space, which represented so much more. The closer was then asked to sign the piece of stone upon which his plaque will be hung for millions of visitors to see.

“It’s starting to sink in now,” an emotional Rivera said. “This is a tremendous and special moment. Signing this plaque, which will be here forever, until the end of the days, is unfathomable. I really can’t comprehend the magnitude of this.”

After he signed his name, Rivera and the group posed for a few photos and then made their way to a conference room in the Hall of Fame offices, where lunch awaited them.

Finally able to decompress, Rivera was still in an emotional and reflective mood.

“I remember leaving Panama for the first time,” he said. “I remember saying goodbye to my father and my mother and my wife, who back then was my girlfriend. I didn’t know what was going to happen in the United States, but I accepted the challenge and I was thankful for the opportunity I had. When I look back now, 29 years later, sitting here in the Hall of Fame, I never could have imagined it would have worked out this way. I never could have dreamed it.”

As the conversation went along, Rivera pointed to his religious faith.

“When people come here and see my plaque, I want them to think about what the Lord did in my life,” Rivera said. “When I came to the United States, I was 20 years old, and I was throwing 87 miles an hour. If a pitcher went to a tryout these days, and he was only reaching 87, the scouts would tell him to go home and keep working on it. But God opened the door for me to grow and to get better, and I did everything I could to honor that.”

Rivera returned to his plaque once more that afternoon for one-on-one interviews with representatives of the two organizations he will forever be linked to, the New York Yankees and the National Baseball Hall of Fame. After a full-day tour, Rivera’s mind was on the larger journey.

“In the video we watched earlier, Juan Marichal said that it’s impossible to believe that he made it from the small town where he grew up in the Dominican Republic to Cooperstown,” Rivera said. “I can sympathize with that. To think that my journey began in Puerto Caimito, a small fishing village in Panama, and that I made it to Cooperstown, that’s unbelievable.”

Alfred Santasiere III is the editor-in-chief of Yankees Magazine. This article appears in the Official 2019 New York Yankees Yearbook. Get more articles like this delivered to your doorstep by purchasing a subscription to Yankees Magazine at yankees.com/publications.