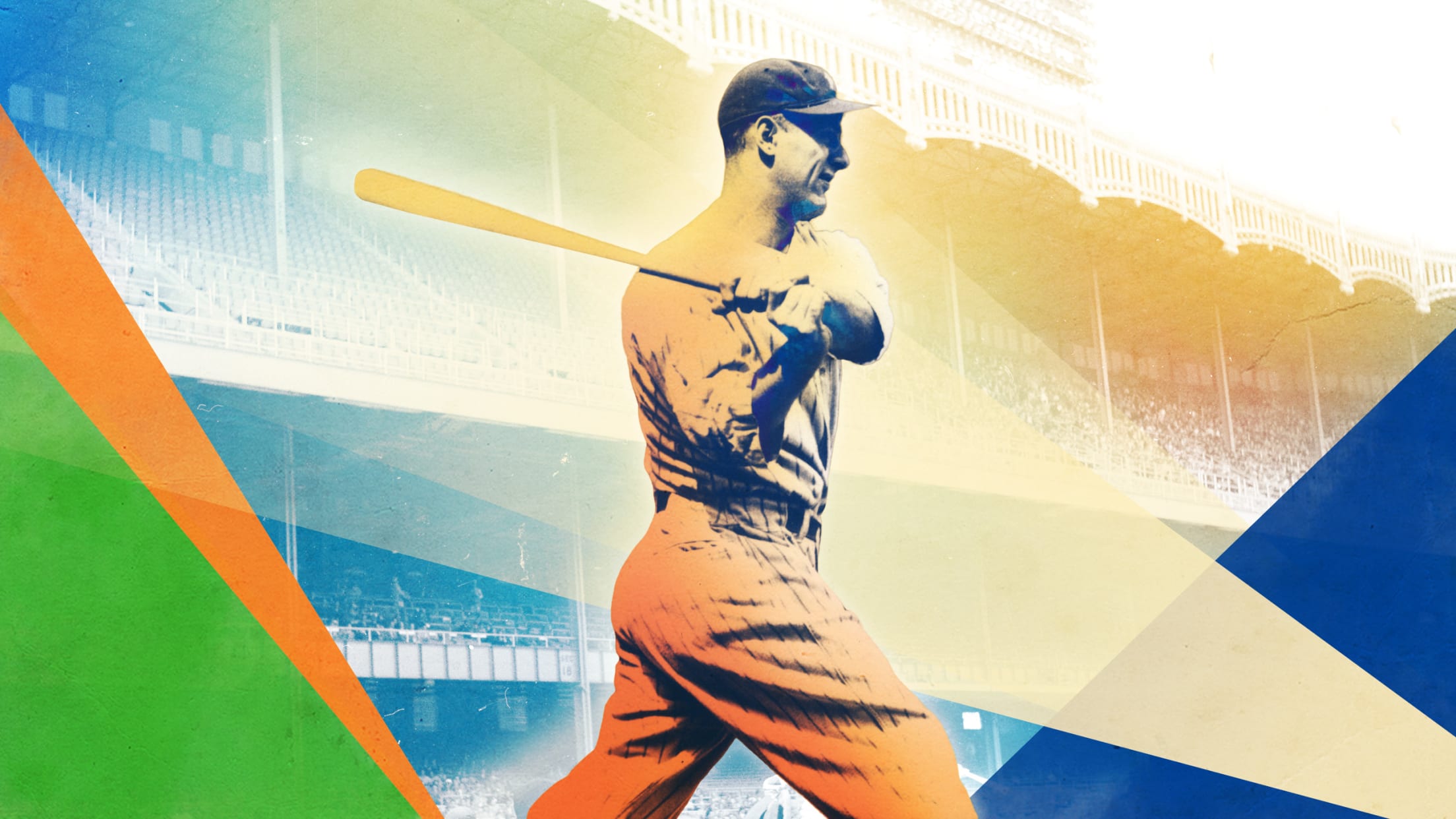

Gehrig's 'worst' season actually was his best

Lou Gehrig’s worst full season was his best.

Despite leading the league in games played (as always), he hit fewer than 30 homers for the first time in a decade, and his batting average dropped nearly 60 points and tied for his career low. His conditioning was questioned, his games-played streak was scrutinized, his All-Star selection was widely lamented. And even when the season ended with his Yankees once again victorious in the World Series, Gehrig’s four singles in 14 at-bats had barely been a factor.

Back in 1938, it would have been preposterous to propose that Gehrig was having his best season, because the prevailing thought at the time was that the “Iron Horse” was running out of steam. But knowing what we know now about both the science and the stats, his ’38 season takes on a much different dimension.

Yes, Gehrig “only” hit .295 with 29 home runs, both of which were disappointing drops from his career norms. But more modern metrics tell us he had a .932 OPS and a 132 OPS+ (32% better than league average) and was worth 4.7 Wins Above Replacement.

More importantly, he did it as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, was beginning to erode him from the inside.

“I almost think it was the greatest season anybody has had,” says Dan Joseph, author of “Last Ride of the Iron Horse: How Lou Gehrig Fought ALS to Play One Final Championship Season.” “He had to start from such a high level of strength and coordination and determination to do this. It’s just astounding to me.”

Or as Jonathan Eig, author of “Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig,” puts it: “It’s superhero stuff.”

As Major League Baseball holds the third annual Lou Gehrig Day on June 2, it’s only natural to gravitate toward the iconic images most often associated with him. We tend to think of Gehrig as Babe Ruth’s partner in power, as Cal Ripken Jr.’s “Iron Man” muse, as the ailing hero who stepped to the microphone and valiantly delivered the “Luckiest Man” speech to a grief-stricken stadium of supporters.

But to get the most complete picture of Gehrig -- to fully understand what he meant to baseball then and what he represents to ALS patients today -- that 1938 season is worth exploring.

Because, in retrospect, Gehrig at his most mediocre (at least, by his lofty standards) was Gehrig at his most inspirational.

The quiet Gehrig, the reluctant Gehrig, the Gehrig who was all too happy to bask in Ruth’s sizable shadow … that’s not the guy we see in “Rawhide.”

Filmed in January 1938 and released two months later by Twentieth Century Fox, “Rawhide” was Gehrig’s most outward embrace of his starpower. At the behest of the brash, pioneering sports agent Christy Walsh, Gehrig had agreed to co-star with singer-turned-actor Smith Ballew in the cowboy flick with an absolutely ridiculous plot.

In it, Lou Gehrig plays … Lou Gehrig, who announces to a group of reporters that he is leaving baseball to retire to a peaceful life raising cattle. Upon his arrival out West, however, Gehrig encounters a nefarious gang that tries to extort protection fees from him and other ranchers. So begins the drama.

“Rawhide” was, deservedly, no box-office smash, and Gehrig did not take home an Oscar to put up next to his 1936 and 1927 American League MVP trophies. (Prior to filming, he didn’t even know how to ride a horse.) Yet Gehrig seemed to relish his first taste of Hollywood, and he expressed a genuine interest in making offseason acting a companion career.

“I’m dead serious about the whole thing,” he told reporters at the time. “This is a new field, and I’m willing to take a whirl at it. In fact, anxious.”

This might not jibe with the prevailing picture of Gehrig as a soft-spoken slugger, but one can’t overstate his eminence in that era. Ruth was long gone from the Yankees' roster, and it was Gehrig who had pointed the way to consecutive World Series titles in 1936 and ’37. Gehrig was on magazine covers and radio programs and newsreels and the Wheaties box. He had one of the most recognizable faces in America. It only stands to reason that they’d want to put that face up on the silver screen.

“He’s really coming out of his shell,” Eig says of Gehrig at that stage. “He’s learning to embrace his celebrity.”

To that point of his life, Gehrig’s story arc had been an unimpeded upward arrow. And long before the words became ironic and iconic, he was the first to admit how lucky he had been.

“I am lucky,” he said at the “Rawhide” premier. “And if anybody wants to argue with me about it, I’ll stand and argue with him all day.”

But as he was suiting up in his cowboy gear and then suiting up for the ’38 season, Gehrig had no way of knowing his luck was running out.

Neurology researchers have offered differing opinions as to when Gehrig’s ALS became symptomatic.

A 1989 paper by Dr. Edward Kasarskis of the University of Kentucky claimed that Gehrig showed symptoms of leg weakness in two scenes of “Rawhide” and that atrophy was noticeable in Gehrig’s hands. A 2006 examination of the movie by researchers Melissa Lewis and Dr. Paul Gordon came to the opposite conclusion, noting that Gehrig, who performed his own stunts, showed “exceptional strength and coordination.”

What is clear, though, is that in Spring Training 1938, Gehrig showed some warning signs that the approaching season would not be up to his usual standard. ALS is quite likely a culprit.

During the exhibition season, there were reports of Gehrig stumbling around the bases, and his wife, Eleanor, later recalled that he admitted that spring to his legs not feeling as “strong or springy” as they once had. Though it didn’t impact his consecutive games streak, Gehrig uncharacteristically missed several tune-up games because of blisters and bruises on his palms, which some authors and researchers have theorized may have been a sign that he was gripping the bat harder than usual to account for the lost power ordinarily derived from his weakened legs and back.

“He had never had problems with blisters before,” Eig says.

Gehrig himself gave the greatest indication that something was amiss at the end of spring camp, in an interview with New York Post sports editor Hugh Bradley that Joseph relays in his book.

“I got to do something about my hitting,” Gehrig told the Post. “I see the ball all right and take a proper cut and seem to connect like I want to, but somehow the ball doesn’t seem to take the proper zoom.”

A decline in power and productivity can sometimes be explained away as a mere matter of time for a baseball player in his mid-30s. Gehrig, who would turn 35 in June 1938, could have conceivably been experiencing the first signs of a mild, inevitable decline that might have arisen even if he hadn’t been stricken with ALS.

[Gehrig] has been in slumps before, but this one is the worst ever. From the stands, it appears as though Lou is out of physical condition. His underpinning is weak. Three times during the Washington series, he was thrown out when he should have made the base easily.

The Daily Eagle newspaper

But Gehrig’s own sense of his body and how it was performing is an important consideration. Months after his ALS diagnosis in 1939, Gehrig would tell the famed sportswriter Grantland Rice that the spring of 1938 is when he first knew something was wrong inside him.

“I knew there was no reason for this,” he said, “as I was still young enough and should have been strong enough. I knew I had kept myself in the best possible condition but lacked the old snap.”

ALS is cruel and merciless. It shuts down the messages from the brain to the body, eventually robbing the patient of muscle control. What Gehrig was probably experiencing in 1938 were the first symptoms of that awful, unstoppable progression.

“We see this every day that our patients are typically like Lou Gehrig,” says Dr. Neil Shneider, director of the Eleanor and Lou Gehrig ALS Center at Columbia University. “They are at the height of their power and career. They’re midlife, often with young families, their career is taking off, and they are reaching a level of power and security that they worked so hard for. Then they’re hit with this.”

It would be another year before Gehrig would be hit with his ALS diagnosis, and even then there was still much to learn about the disease. But his 1938 season would be a true test of his ability to adapt, adjust and overcome as his body began to inexplicably betray him.

Gehrig could sense something was amiss with his swing during Spring Training. And by the end of April, everybody knew it. Through the season’s first 13 games, he was saddled with a .116 average and had yet to hit a home run.

A celebrity of his stature was not going to endure such a skid without it becoming headline news.

“[Gehrig] has been in slumps before, but this one is the worst ever,” wrote the Daily Eagle. “From the stands, it appears as though Lou is out of physical condition. His underpinning is weak. Three times during the Washington series, he was thrown out when he should have made the base easily.”

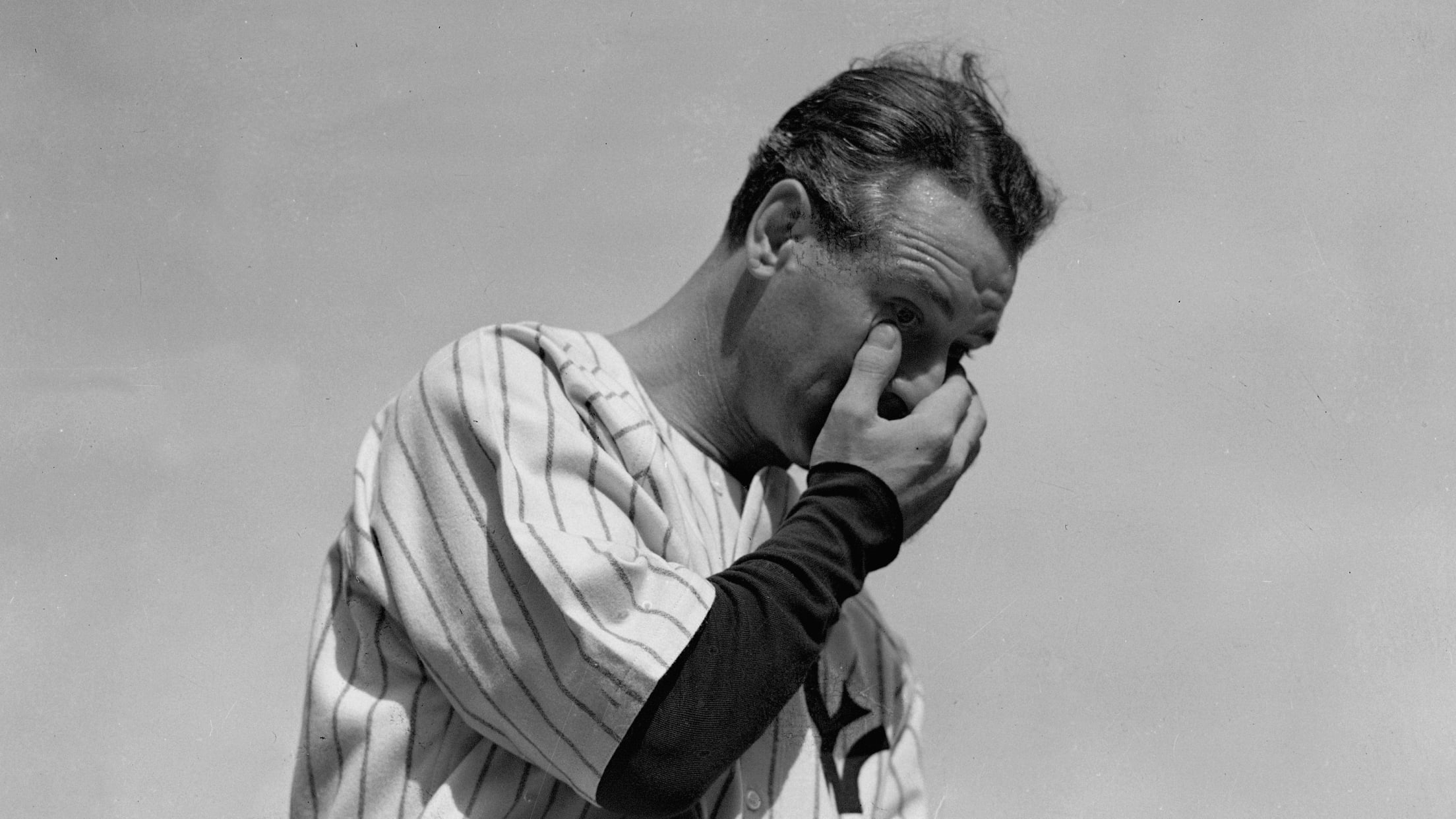

In terms of his batting average, Gehrig’s start to 1938 was even worse than what he would endure in the first eight games of 1939, when he hit .143 in the season’s first eight games, pulled himself out of the starting lineup to end his record games played streak at 2,130 and wound up visiting the Mayo Clinic to receive his grim diagnosis.

If you don’t play, they’ll write about you for days and everybody will say, ‘That’s some colorful ballplayer.’ And if you do play, you know what you’ll get out of it? A paragraph [in the newspapers] and a floral horseshoe.

Eleanor Gehrig, on the streak

The difference is that, in 1938, Gehrig kept going, kept playing, kept extending his streak even when it ceased to make sense. Gehrig had to be replaced by young Babe Dahlgren in the middle of a May game because of a lower back injury that was severe enough to require him to wear a plaster cast afterward. The following day’s game was, mercifully, rained out, but there is little doubt that Gehrig, just eight games shy of reaching 2,000 consecutive, would have suited up for it even if the rain hadn’t granted him a needed day of rest.

“The streak seems to have taken on a life of its own, as it did for Ripken,” says John Thorn, MLB’s official historian. “The idea that you have to be in every game to be of value to the club, as opposed to taking a rest, is nonsense.”

Eleanor Gehrig apparently agreed. In a 1941 interview, she said she implored her husband to stop the streak at 1,999 games.

“If you don’t play,” she recalled telling Gehrig, “they’ll write about you for days and everybody will say, ‘That’s some colorful ballplayer.’ And if you do play, you know what you’ll get out of it? A paragraph [in the newspapers] and a floral horseshoe.”

Gehrig, though, was not going to upend the Yankees’ plans to celebrate No. 2,000. Nor was he going to stop at 2,000. The streak marched on, even when Gehrig fractured his thumb in July and even amid the growing public cries to give his diminished bat a rest.

“The darn thing’s gotta end some time,” wrote Lester Rodney in The Daily Worker (which, yes, covered sports in addition to reflecting the views of the Communist Party). “How about now, when you plainly show that you could use a rest, Lulu?”

Again, this is where it is difficult to draw a distinction between the expected wear and tear associated with a mid-30s player in the midst of a to-that-point-unprecedented games-played streak and an ALS patient experiencing his first symptoms.

But fatigue, muscle cramps and weakness in the legs and arms are among the initial effects of ALS and can persist -- perhaps tolerably, but noticeably -- for about a year before the more serious deterioration in ability begins. So it is absolutely reasonable to assume that Gehrig’s difficult start to 1938 was not entirely age- and streak-related.

Whatever the case, Gehrig’s unusually uninspired season wore on. And he did everything he could think of to snap out of his skid, including altering his stance and his bats.

“I went and got the archival order history on his bats from Louisville Slugger and learned that he was ordering lighter bats,” Eig says. “He had used the same bats his entire career [up to that point]. He was a creature of habit and would not have changed his bat capriciously.”

Gehrig’s numbers did begin to improve as the season evolved. But his home runs were often solo shots, and, on a Yankees team that spent much of the first half trailing Cleveland in the AL standings, he struggled to come through with the clutch knocks he had been known for (Gehrig’s career grand slams record stood for 73 years). He was batting .267 on June 23, which is when the Sporting News ran the front-page headline: “Old Iron Horse Not What He Used to Be.”

The Iron Horse reputation, however, was still strong enough to land Gehrig a spot on the American League squad in the sixth annual All-Star Game. With the Indians’ Hal Trosky left off the roster despite having an objectively superior season, there was tremendous backlash against Gehrig’s selection, which was made via a vote of all eight of the AL managers.

“Whatever has the Iron Horse done this year to entitle him to selection?” wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer. “He is putting on the poorest batting front of his career, which is one of the principal reasons that the Yankees do not occupy the top place.”

Somehow, life went on. But the All-Star experience had only given the papers more ammo in the effort to point out how un-Gehrig-like 1938 had been.

For one amazing stretch later in the summer, however, no such ammo existed. In a 25-game stretch from Aug. 7-26, Gehrig went on an absolute tear, batting .352 with nine homers, eight doubles, three triples and 36 RBIs. Accordingly, it was a stretch in which the Yankees gained the double-digit lead in the AL standings that they would not relinquish.

“He went back to being the normal, superpowered Lou Gehrig that everybody knew,” Joseph says. “All season he was a .270 hitter with occasional power. Then suddenly, it was home run after home run.”

It could simply be that Gehrig got his groove back because of an adjustment in his swing. But Joseph’s book posits that Gehrig may have been experiencing a temporary reversal of his ALS symptoms. A 2015 study by Dr. Richard Bedlack of Duke University found that nearly 1 in 7 ALS patients examined showed brief improvements in their ability to speak, walk, breathe and perform motor functions -- perhaps as a result of surviving motor neurons reconnecting with the muscles.

“There’s a lot of day-to-day variability [in newly stricken ALS patients],” Shneider says. “There are issues like cold weather. ALS patients don’t like cold weather. And they get very stiff. So maybe it was the warm weather of August that made him feel a little less spastic and stiff, and he returned to some normal level of function.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t last.

By September, the great Gehrig was a singles hitter yet again. He remained that way the rest of the year, including the World Series, in which the Yankees swept the Cubs with little input from their first baseman. (He did, however, earn some MVP support and finish 19th in the voting that year.)

The most distinct demonstration of Gehrig’s sapped strength -- and the biggest tip-off to what awaited him in 1939 -- came in a home run-hitting contest staged against the St. Louis Browns prior to a Sunday doubleheader. Six players participated -- Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and George Selkirk of the Yankees, and Harlond Clift, Beau Bell and Mel Mazzera of the Browns. Gehrig was unquestionably the most accomplished power hitter of the group, and yet he finished dead last in the derby.

On Sept. 27, 1938, when Gehrig connected on a 3-0 pitch from the Washington right-hander Dutch Leonard in the fifth inning and drove it into the Senators’ bullpen, it was the 493rd and final home run of his career. One last huff from the Iron Horse.

The rest of Gehrig’s baseball story is familiar and tragic.

Come Spring Training in 1939, his lack of coordination was concerning, and his speed and strength had vanished. It took him all of eight regular-season games to know it was time to bench himself. And though he still held out hope of returning to the lineup for a time, it was after an early June batting practice in which he struggled to hit the ball out of the infield that he finally resolved to seek the opinion of medical professionals.

From the day he was diagnosed, Gehrig, who passed away on June 2, 1941, has stood as a symbol in the ongoing fight against ALS. After all, if the disease could cut down the Iron Horse, it could claim any of us.

“It’s hard for people in 2021 to understand what an unusual celebrity Lou Gehrig was in 1939,” Shneider says. “I don’t know that anybody else could have brought as much attention to the disease as he did. Nobody in 1939 knew what ALS was, including people who had it.”

Doctors have worked tirelessly but fruitlessly to develop a cure. But thanks in part to the generous donations of the Eleanor and Lou Gehrig estate, clinical trials like the ones conducted at the ALS Center that bears their name have created a greater understanding of the biology of the disease.

“Genetics have provided important insights into how this disease happens and how things go wrong in people’s motor neurons,” Shneider adds. “That has led to designs of therapies that are much more promising than the ones that have been in trial over the last decades. There are gene-based therapies that have a real potential to alter this disease and significantly improve and extend patients’ lives. Even though it hasn’t yet translated into a kind of treatment that makes our patients’ disease very different from Lou Gehrig’s, it’s coming.”

Until then, ALS patients can only do what Gehrig did in 1938 -- stage a valiant, if unwinnable, fight. Gehrig’s approach to his craft in his final full season -- his unyielding attempt to adjust his swing, adapt his style and wring whatever remaining hits he could out of his once-booming bat, all while maintaining an extraordinary games-played streak -- is a marvel.

“The fact that he was able to play that whole season was just amazing,” Joseph says. “Your body is beginning to shut down. Your muscles are getting disconnected from your brain. And yet he was able to play every single game, he still had 29 home runs, he still drove in 114 and he was still the first baseman on a team that won the World Series. How does he do that? How does anybody do that?”

Adds Eig: “You can make an argument that it’s the greatest individual performance in baseball history.”

It was Gehrig’s worst season. And it was his best season. Though his numbers began to plunge from his pristine peak, Gehrig emerged as a towering figure in a much more meaningful fight.

Dan Joseph’s “Last Ride of the Iron Horse” is published by Sunbury Press and Jonathan Eig’s “Luckiest Man” is published by Simon & Schuster.

A version of this story was originally published on June 2, 2021