There’s nothing like a great baseball story. But baseball has been around a long time, and in some cases, it can be hard to tell whether those stories are too good to be true. Which is why MLB Mythbusters is here to help -- we'll be diving into some of the game's greatest legends, trying to separate fact from fiction.

Next up: Taking a second look at one of the game's most infamous scapegoats.

The myth: Bill Buckner cost the Red Sox the 1986 World Series -- and prolonged the Curse of the Bambino

The context: After nearly seven decades -- seven long, excruciating, championship-less decades -- Boston has finally made it. The Red Sox have ridden a deep, well-balanced roster to 95 wins and an American League East crown, their first in 11 years. They've outlasted the Angels in a bruising, seven-game AL Championship Series, thanks in large part to not one but two dramatic rallies in Game 5 -- the sort of back-breaking, series-swinging improbability that usually happened to the Red Sox, not for them.

And now, in their first World Series since 1975 (and just their fourth since 1918), Boston has risen to the challenge against the powerhouse Mets. They knocked Doc Gooden around en route to taking the first two games at Shea. They got a complete game from Bruce Hurst to win Game 5, giving themselves a 3-2 Series lead and putting them just nine innings away from that long-elusive World Series crown. Then, in the seventh inning of Game 6, they got their big break: With the game tied at 2, an error by New York third baseman Ray Knight put runners on the corners, and a Dwight Evans groundout gave the Red Sox the lead.

Nine outs away. Roger Clemens dealing on the mound. Time to put the ghost of the Babe to bed.

The evidence: Or, uh, not.

Clemens didn't come back out to start the eighth ... at which point the Mets promptly pushed across a run to force extras. Boston -- thanks to another big Dave Henderson home run -- scored two in the top of the 10th, again putting themselves on the doorstep. But again, it wasn't enough: Needing just one out to secure the title, reliever Calvin Schiraldi surrendered three straight singles and a wild pitch, tying the game once more and putting Knight on second as the winning run. You probably remember what happened next:

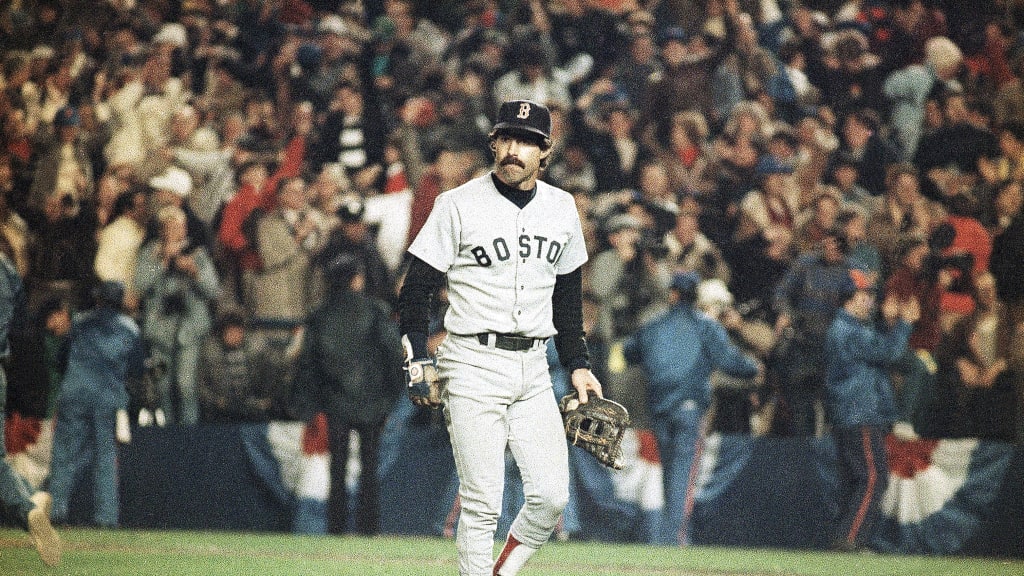

The ball got by Buckner, Knight came around to score and the Amazins had won Game 6. Two days later, they'd won the World Series -- while the Red Sox were doomed to spend another winter wondering how things had gone so horribly wrong. Keith Hernandez became a "Seinfeld" character; Mookie Wilson became a cult hero; Buckner became one of the most notorious goats in the history of American sports, his last name practically shorthand for "you blew it."

The argument for: At first glance, it's not hard to see why. I mean, go watch that play again; the ball seems to mosey along, almost slowing down as it passes first base. It's not just the sort of play that you expect a Major Leaguer to make 100 times out of 100 -- it's the sort of play that everybody watching at home, fairly or unfairly, could imagine themselves making.

In the immediate aftermath of another crushing loss, another year ending in heartbreak, another year of getting trolled by the entire city of New York, it's no wonder that New England decided to put all of its misery onto Buckner. All he had to do was keep his glove down! All-Star Dwight Evans was set to lead off the top of the 11th! As a fan, what's easier to fixate on: one ordinary ground ball, or every single moment, big and small, that's gone into nearly 70 years without a World Series title?

The argument against: Of course, just because it's easy doesn't mean it's true.

For starters, there's a decent chance that even if Buckner had fielded that ground ball cleanly, it wouldn't have mattered. Wilson was one of the fastest men in baseball, a 50-steal player in his prime, running with a head start from the left side like the entire season was riding on his legs. Buckner, on the other hand, was about to turn 37, suffering from such severe chronic soreness in both of his ankles that he'd needed nine cortisone shots over the course of that season -- and some special high-top cleats, the first Major Leaguer to ever wear them -- to try to manage the pain. (We'll come back to this, I promise.)

Even having made the play, he's still flat-footed, several steps behind first, with Wilson coming with a full head of steam and pitcher Bob Stanley nowhere in sight. Camera angles from the broadcast don't allow us to know exactly how far up the line Wilson was when the ball reached Buckner's glove, but several eye witnesses -- including Wilson himself after the game -- swore that they thought he was going to win that race to the bag.

Let's say he wouldn't have, though. Let's grant that, if he'd come up with the ball, Buckner would've made the play and ended the inning. Even under those circumstances, he's still pretty far down the list of things at fault for what happened to Boston in the '86 World Series.

• Buckner's aforementioned ailing ankles beg the question: Just why was he out there to misplay that grounder in the first place? The Red Sox won seven games that October, and in all seven, manager John McNamara had swapped out his veteran first baseman for a defensive replacement in the later innings -- typically Dave Stapleton, a utility man who couldn't hit much but had earned a place on the postseason roster because of his ability to field several different positions. And yet, with Boston trying to salt away arguably its biggest win ever, Buckner stayed in the game. Maybe McNamara wanted to keep him out there for the final out; maybe he just froze. Whatever the reason, it's clear that Buckner wasn't put in a position to succeed.

• Speaking of McNamara's decision-making: When Clemens left the game following the bottom of the seventh -- maybe or maybe not against his will, no one's quite sure -- the Red Sox held a 3-2 lead. And yet, when Wilson's ground ball rolled between Buckner's legs, the score was tied -- thanks to reliever Schiraldi, who blew the lead not once but twice over the course of 2 2/3 innings. Schiraldi had been big down the stretch for McNamara, but his outing in Game 6 was basically doomed from the get-go: He gave up a single to the first batter he faced, Lee Mazzilli, who'd eventually come around for the tying run ... while Schiraldi looked like he'd rather be anywhere else:

• Schiraldi stayed out there for the 10th, bringing the Red Sox just one out away from winning it all. Again, the wheels came off: Three straight hits put the tying run on third and knocked him out of the game with Wilson due up. • In came Stanley, Boston's closer for most of the season. Still, the Red Sox were an out away. The game was in their hands ... until Stanley uncorked a wild pitch past catcher Rich Gedman, allowing Kevin Mitchell to score and tie the game again. After the game, players claimed that there'd been a miscommunication between the two -- some said that Gedman was expecting a sinker rather than a four-seam fastball, while Stanley maintained that Gedman set up outside for a pitch that was supposed to be thrown on the inside corner. You be the judge:

• And even then: That was only Game 6! The Red Sox still had another chance to break the curse two nights later, only to blow yet another lead (thanks in large part to another rough relief appearance from Schiraldi, who allowed three runs in 1/3 of an inning and took the loss).

The verdict: Bad ankles that had hobbled him all year. A manager who inexplicably left him in a position he hadn't been in all postseason -- and made several other questionable moves. A bullpen that blew not one but two late-inning leads. A catcher who missed a sign.

Despite all that, Buckner has taken the fall for the Red Sox' historic collapse, a victim of being in the wrong place at the wrong time -- the man who happened to be on-screen when New England's long-awaited celebration turned into yet more heartbreak. Obviously Buckner should've made the play. He said as much in the decades since before his passing away in May of last year. But he's not the one who lost the game, or the series; he simply put the exclamation point on an unthinkably bad night.