Surveys were conducted. Plans were concocted. Experiments were administered. And decisions were made.

At the outset of the 2023 season, Major League Baseball ushered in a series of rules changes -- the pitch timer, bigger bases and defensive shift limits -- that were arguably the most ambitious in the modern era. Upon the urging of the fans, the goal was a quicker pace with more action.

Here at the season’s ceremonial midpoint, the result of these revisions could not be clearer.

“You got what you asked for,” Dodgers star Mookie Betts said during the All-Star Game festivities. “They did exactly what they were intended to do.”

Whether you love, hate or are indifferent to change in this sacred sport, Betts is absolutely right. The rules have, indeed, delivered more action in less time, and we have plenty of numbers to prove it.

When compared to other recent MLB seasons, more action in less time is a radical concept. In an evolution brought about by analytics, modern managing and player behavior, the game had ventured down an unmistakable, uninterrupted path toward more time for less action.

That didn’t distill the drama of the pennant races. It didn’t drown out the wonder of walk-off wins and crazy comebacks. It didn’t make the hot dogs or the freshly cut grass suddenly smell worse. But three-hour games with four minutes between balls in play was an increasingly tough sell to a populace with no shortage of extracurricular options, and there was really no reason to believe things would improve organically.

So the powers that be dreamed up some changes aimed not at creating some new, unrecognizable version of the game but, rather, stripping away some of the unnecessary -- and, frankly, unentertaining -- aspects of game play that had become too cumbersome and too commonplace.

The results have been striking.

“Athleticism is playing up,” Braves ace Spencer Strider said. “Guys with individual tools are able to showcase them more.”

That’s led to some impressive and potentially historically significant statistical paces. It also could be contributing to some of the standings surprises that have been a prime storyline of the season.

Here are some observations on what the new rules have wrought thus far this season:

1. The pitch timer works.

Unequivocally. It was adopted to cut out dead time, and the mission was accomplished.

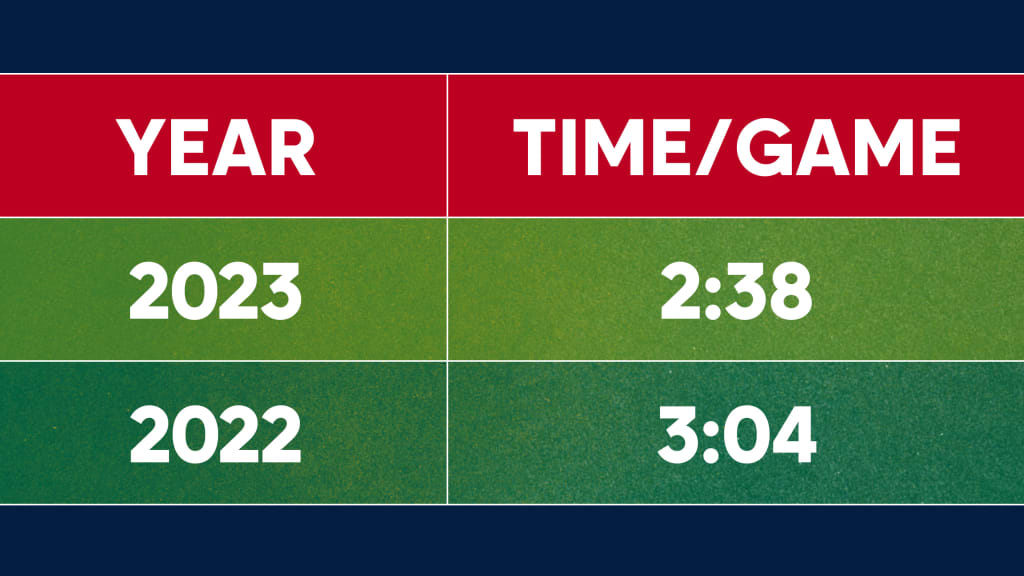

When comparing the average nine-inning game time from the first half of 2023 to the first half of 2022, we see a decrease of 26 minutes:

That still hasn’t gotten us to the average of 2:30 that was the most oft-cited “ideal game time” in surveys of fans. But we’re a heck of a lot closer than we once were. The average time of a nine-inning game is now lower than it’s been in nearly 40 years. It’s given players more opportunity to rest their bodies from the grind.

“Any extra time I can get with my two boys and my wife is great,” said Yankees ace Gerrit Cole. “And the New York traffic can be a grind. So getting home at 11 instead of 12 or 12:15 on a regular basis is really great. I don’t feel the quality of the game has dropped at all. In fact, I think it’s actually kind of picked up to a certain extent.”

To that point…

2. Less time hasn’t meant “less baseball.”

As a matter of fact, there were more runs scored per game in the first half of the inaugural season with the pitch timer (9.14) than there had been at the same stage in 2022 (8.66).

What was removed were all those empty hours of players adjusting their batting gloves, walking around the mound, etc.

“It’s moved pretty seamlessly,” Braves first baseman Matt Olson said. “You're able to wipe off half an hour every game. I think it's good for fans, and I think it's good for players and their bodies and recovery. You know, there might be a time or two where you feel a little rushed. But I think by the end of the year and going into next year, you won't even notice anything about it.”

On that note…

3. Players have adjusted.

On the very first day of the Grapefruit League season, there was much public discussion about a game ending on an automatic strike assessed to a batter who violated the pitch timer with the bases loaded, two out and the count full in the bottom of the ninth. Some were flabbergasted by the blasphemy of a ballgame ending in such a way (never mind that the game ended in a tie rather than going to extra innings because it was a meaningless exhibition).

But that moment was confirmation that the new rules would, indeed, be enforced strictly all spring. And the benefit of that strict enforcement is what we’ve seen in the regular season.

Though there have been -- and will continue to be -- moments when players or managers take issue with an enforcement, it did not take long for the timer to mostly fade into the background. In the first 100 games of the regular season, there were 0.87 violations per game and 57% of games played had at least one violation. In the last 100 games before the break, there were 0.50 violations per game, and, in total, 60% of games this season have been played without any violations. Only 11.9% of games have included multiple violations.

“It was definitely an adjustment period,” said D-backs ace Zac Gallen. “Spring Training was tough, for sure. But I think, just like everybody else, we just adapt.”

4. Pitchers have had plenty of time on the clock.

This is an important point amid news that the MLB Players Association would like to add time to the clock for the postseason. The pitch timer rules allow for 15 seconds between pitches when the bases are empty and 20 seconds when runners are on.

By and large, that’s proven to be plenty of time.

Pitchers have, on average, begun their throwing motions with 7.9 seconds left on the timer after between-innings breaks, 7.0 seconds remaining after a new batter came to the plate, 7.5 seconds remaining with runners on and 6.6 seconds with the bases empty.

5. The stolen base is back.

The running game had fallen by the wayside in the modern game, as teams became more risk-averse because of the analytical assessment of the value of outs. That didn’t just impact the way games were managed but also the way players were developed and rostered.

But the new rules -- pickoff limitations placed on pitchers in connection with the pitch timer and the increase of first base, second base and third base from 15 inches on each side to 18 inches on each side -- were widely expected to inspire more bravery on the part of baserunners.

They’ve done just that. Here are the numbers comparing the first half of 2023 to the first half of 2022:

That rate of attempts per game is on pace to be the highest since 2012. And the leaguewide success rate was on pace to be the highest in history. The disengagement limit had reduced pickoff attempts by 1.1 per game.

No one has taken advantage of this environment more than Braves star – and early NL MVP favorite – Ronald Acuña Jr. With 41 steals in 89 team games, he has already surpassed his career-high tally of 37 in 2019 and become the first player with 40-plus at the break (along with Oakland rookie Esteury Ruiz) since Billy Hamilton (44) with the 2015 Reds. Having also hit 21 homers, Acuña has a very real chance of becoming the first player in history with a 40-homer, 70-steal season.

Combine a .408 on-base percentage with an aggressive mindset and the intelligence to know when to go, and Acuña just might do it.

“No doubt,” his Atlanta teammate Ozzie Albies said. “Keep playing his game the way he does, and it’s gonna happen. Nothing is impossible with him.”

What will be interesting to see, in the long run, are the changes that come to player development as a result of these new rules. Speed was a popular target in this week’s MLB Draft. The stolen base’s comeback tour might just be beginning.

6. We’ve seen more hits on balls in play.

Ted Williams hit .406 in 1941. Five years later, in the middle of Williams’ first MVP season, Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau debuted the Ted Williams shift by stacking the right-hand side of the infield against him. Williams didn’t hit .400 that year or ever again.

And neither has anyone else.

The shift is, of course, not the only reason we’ve gone so long without a .400 hitter. You can also blame player approaches, a bevy of electric relief arms, etc. But the extreme shifts based on analytic input that became ubiquitous in the 21st century sure didn’t help.

Suddenly, here in 2023, we have a player in Marlins second baseman Luis Arraez who is chasing .400. Odds are, he won’t come close. Arraez took a .383 average into his All-Star appearance after batting .324 in his first nine games in July. But to even be batting .380 or better at the break is notable. Arraez was the first to do it since Boston’s Nomar Garciaparra (.389), the Angels’ Darin Erstad (.384) and the Rockies’ Todd Helton (.383) in the enormous offensive environment of 2000.

The defensive shift limits have certainly contributed to Arraez’s cause. Last year, the left-handed-hitting Arraez led the AL with a terrific but hardly historic .316 mark and had only a .120 average on pull-side groundballs. Those batted balls accounted for only 5% of his hits.

This year, with teams required to field two infielders on each side of second base and within infield territory, Arraez is batting .224 on groundballs to the pull side. Those hits have accounted for 8.7% of his hits, and they add up on this .400 chase.

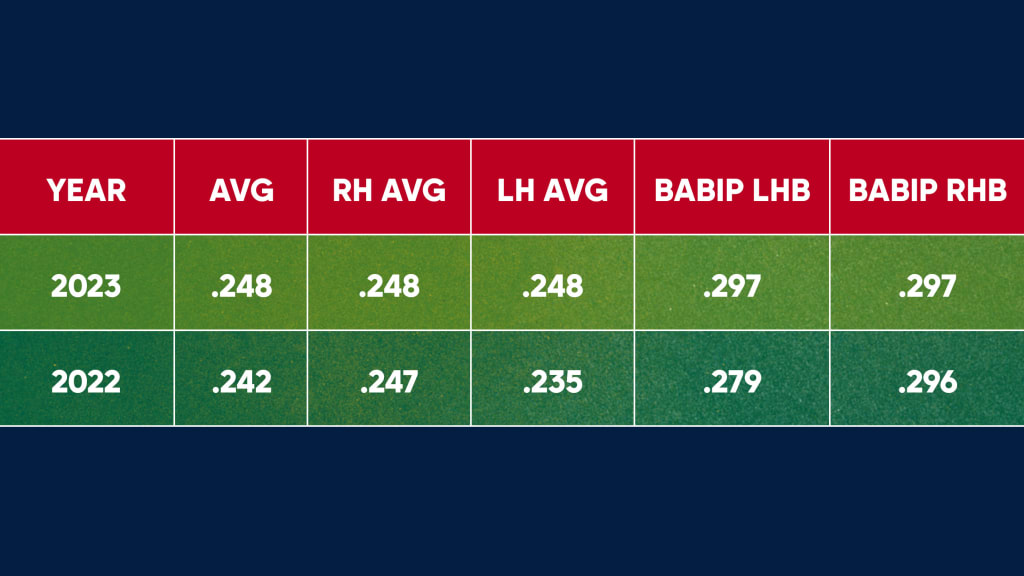

In limiting shifts, MLB tried to turn back the clock and generate more traditional results on balls in play. This is another rule change that will best be viewed in the long run, as it could greatly impact the way teams develop hitters. But for now, it has had some impact on the batting average on balls in play (BABIP), particularly for left-handed batters, as you can see from the numbers comparing last year’s first half to this one:

Notably, lefties have seen their BABIP on pulled groundballs increase by 40 points and pulled line drives increase by 32 points.

This has not rid the game of the perpetual increase in the so-called Three True Outcomes. The home run rate is up, from 2.2 to 2.3 per game. The strikeout rate is up, from 16.7% to 17.2%. The walk rate is up, from 6.2% to 6.5%.

But there are more players on the basepaths (overall, OBP has increased from .312 to .320), and more of those players are blazing the basepaths. It’s simply a more entertaining offensive environment.

“Totally, it’s fun,” Albies said. “You know, you have activity all the time, every inning, so that makes the game more fun because there’s always a play.”

That keeps fans – and fielders – more engaged.

“Honestly, it's better for defense,” Olson added. “You see guys showing off their range.”

7. We’ve seen surprising results.

At the All-Star break, three divisions had a different leader than they did at the end of 2023, and another – the NL West – had a tie between last year’s winner (the Dodgers) and last year’s fourth-place finisher (the D-backs). If the postseason began today, half of the 12-team field would be different this year than last.

It’s impossible to prove that the new rules – including the more balanced schedule – play a part in these surprises. But there is no denying that athletic teams like the Reds, D-backs, Rangers and Orioles – all of whom were on the outside looking in last year and are currently on the inside looking out – have taken advantage of this brisker environment. They all rank at or above the league average in stolen-base percentage, they all rank in the top five in extra-base-taken percentage (as calculated by Baseball-Reference), and all but the Reds rank above league average in defensive runs saved above average.

So there might be something to this hypothesis.

“I think so,” Brewers ace Corbin Burnes said. “And I think you kind of see it as teams are developing players, as well, they want those guys that are fast and can steal bases.”

Combine all of these elements – more surprises and more action in less time – and you have a compelling product. This is reflected in attendance, viewership and social media engagement increases.

The surveying, planning, experimenting and decision-making led to rules that have done as intended, ushering in a better version of baseball.