Imagine being named after the home run, the great symbol of baseball, and having to live up to it.

Who would be worthy of such a moniker … the likes of Babe Ruth, maybe, or Willie Mays, or Hank Aaron. But they have their own nicknames: the Sultan of Swat, and the Say Hey Kid, and Hammerin' Hank.

Which brings us to Home Run Baker.

Go look at Baker's baseball encyclopedia page. The Hall of Famer, born on this day in 1886, was a .307 hitter over a 13-year career. But the question is obvious: How in the world did the player nicknamed Home Run only hit 96 of them?

There's a story behind it, of course. Here's how Home Run Baker became Home Run Baker.

Before he was Home Run

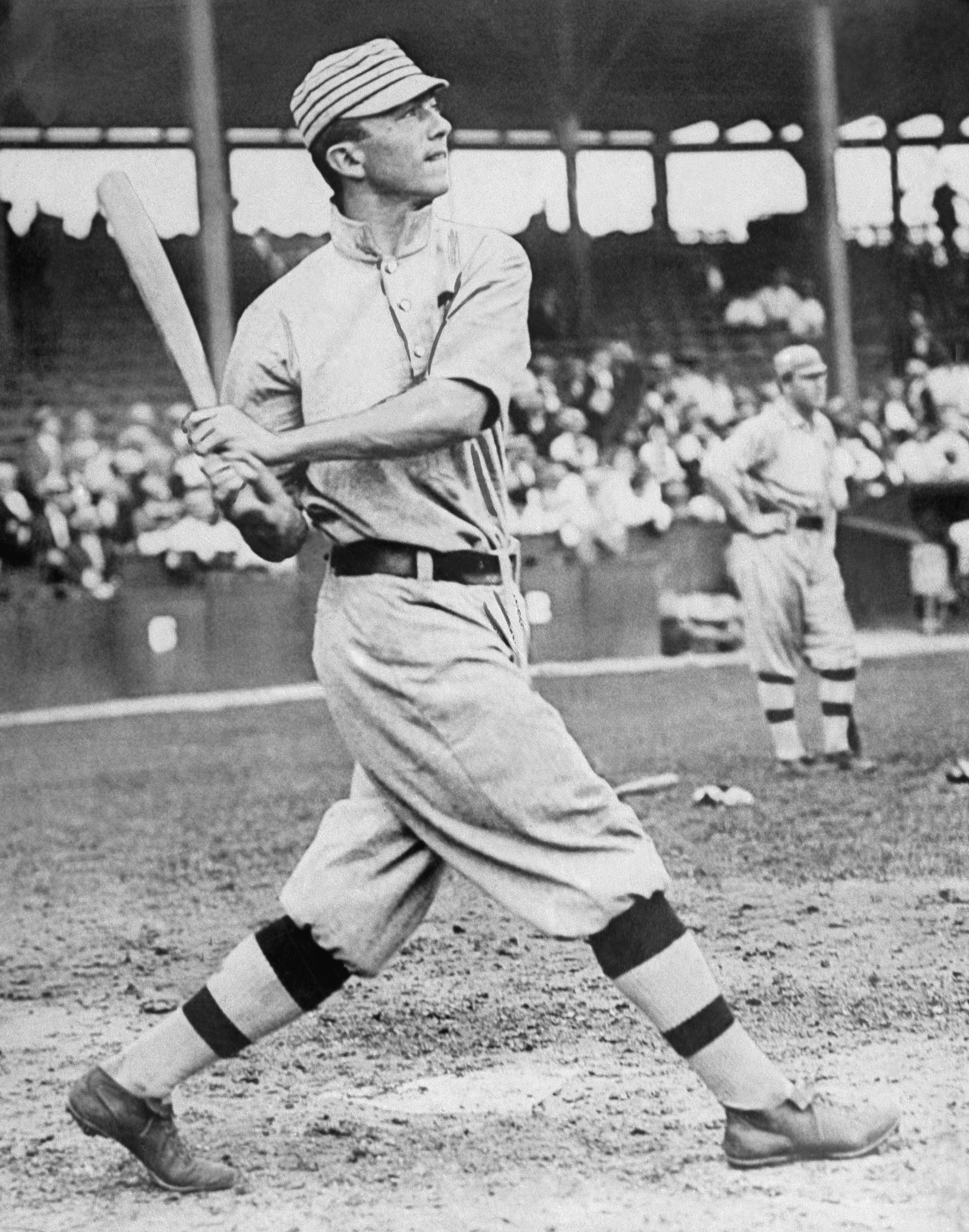

Frank Baker started his career in the heart of the Deadball Era. At first, he wasn't a home run hitter at all, even for a Deadball player. Baker hit only four homers for Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics in his first full season in 1909. The next year, he hit only two.

The 1911 season is when the Home Run legend was born. Baker turned into a slugger (by Deadball standards), knocking 11 home runs. Today, that's not even a power hitter. In 1911, it was enough to win the American League home run crown.

The lefty-hitting third baseman -- known for using an exceptionally heavy 46-ounce bat -- finished ahead of Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, who hit eight homers each.

But that's still not why he got the nickname Home Run.

1911 World Series, Game 2

Baker had actually been referred to by the Home Run nickname on a few scattered instances back in his barnstorming days, but it was the 1911 World Series that made "Home Run Baker" a national name.

The A's, reigning World Series champions, had won 101 games to run away with their second straight AL pennant. In a Fall Classic clash of baseball's early titans, they were facing John McGraw's New York Giants.

Baker, though he was the league home run leader, wasn't the superstar hitter on his own team -- that was Eddie Collins. And though Baker had starred in the previous year's World Series, batting .409 in Philadelphia's win over the Cubs, he'd also gone homerless. That was about to change.

Game 2 at Shibe Park was a pitchers' duel between Hall of Famers, Philadelphia's Eddie Plank and New York's Rube Marquard. The A's were trailing in the series, having dropped the opener at the Polo Grounds, as Chief Bender was outdueled by Christy Mathewson and Baker was spiked hard at third base by the Giants' Fred Snodgrass. In Game 2, the score was tied, 1-1, in the sixth inning when Baker, batting cleanup behind Collins, stepped to the plate against Marquard.

With two strikes, Marquard left a fastball up and over the inside part of the plate, and Baker turned on it and drove it into the right-field seats for a tiebreaking two-run homer. The A's won the game, 3-1, and evened the series.

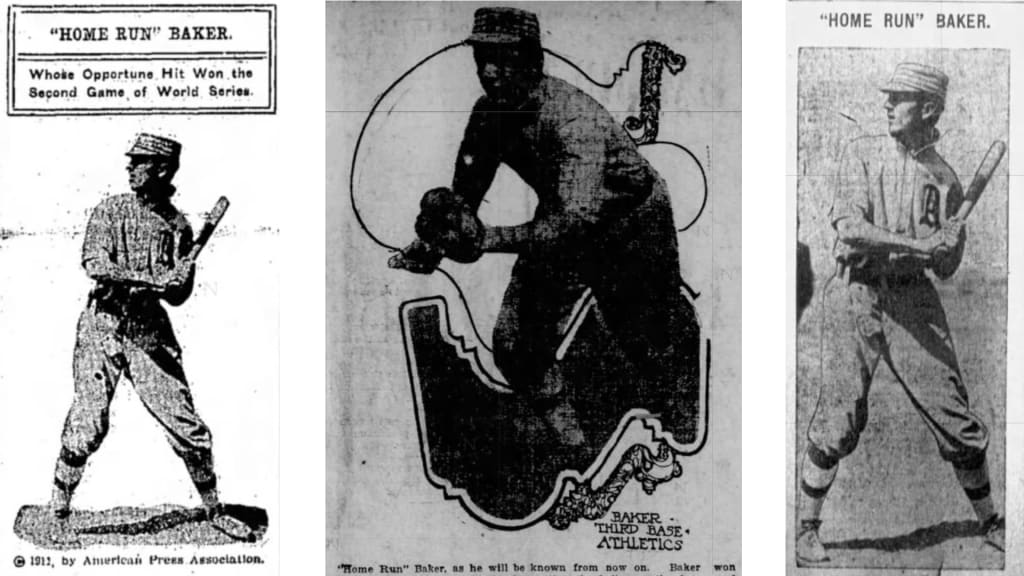

The next day, Frank Baker was Home Run Baker … in the words of none other than the opposing catcher. The Giants' Chief Meyers, in a firsthand account of Game 2 published in the San Francisco Examiner, described Baker's homer in great detail.

"Marquard tried a fast straight one, close inside. We know now to our sorrow that just such a ball is exactly what Frank Baker would call for if he were given his choice of a hundred different sorts. I watched him swing back, then lunge forward and with the crack of the bat I knew something was coming off. I looked over to right field and saw the ball going higher and higher against the background of those brown stone houses on Twentieth Street. It must have cleared the fence by ten feet …

"Marquard did well, too. I want all our followers to have just as much confidence in him in the future as I will. He's good to go back again tomorrow and stand Mr. 'Home Run' Baker on his head."

If only he knew what was going to happen the next day.

1911 World Series, Game 3

Game 3 cemented the legacy of Home Run Baker.

The series was back at the Polo Grounds, and Mathewson was back on the mound for the Giants. He took a shutout into the ninth inning, with New York leading, 1-0. That's when Baker came up.

Mathewson threw Baker a curveball, and to everyone's shock, Baker crushed the game-tying home run to the deep right-field grandstand. The A's went on to win the pivotal game in 11 innings, handing Mathewson the first World Series loss of his career.

Everyone wanted to know just how Baker had managed to homer off Marquard and Mathewson. He obliged.

"There seems to be much speculation regarding what sort of balls were pitched when I made my home runs off 'Rube' Marquard and Christy Mathewson," Baker said after Game 3. "Well, I hit them and I know what kind they were. Matty threw me an in-shoot, but that would have been an out-shoot to a right-handed batter, while the 'Rube' threw a fast one between my shoulder and waist. When I faced Mathewson, I set myself and looked them over. When Mathewson pitched me that curve and I saw her starting to break, I busted her, that's all."

He added: "Marquard's high one Monday looked too good to be true. Another in the same spot seemed impossible."

The back-to-back game-changing home runs -- off two Hall of Fame pitchers -- put Baker's name in all the papers. Now he was Home Run Baker everywhere.

"'Home Run' Baker tied the score with a circuit clout in the ninth," wrote the Brooklyn Standard Union.

"The 'invincible Matty' is no more invincible," wrote the Kansas Evening Herald, thanks to "the devilish bat of 'Home-Run Baker.'"

And the Philadelphia Inquirer described how fans "saw 'Home Run' Baker bang another sizzler for a free circuit of the runways and tie the score in the ninth orgy when it seemed as though 'Matty' was going to twirl the Giants to another triumph."

Headlines trumpeted the name HOME RUN BAKER in all caps. "McGraw instructs his twirlers what to dish up for Home Run Baker," read the New Castle Herald's, placed atop a game story written by the legendary Grantland Rice. "Home Run Baker is there with his wallop," said the Wilkes-Barre Record's. "Home Run Baker does it again," said the New York Sun's.

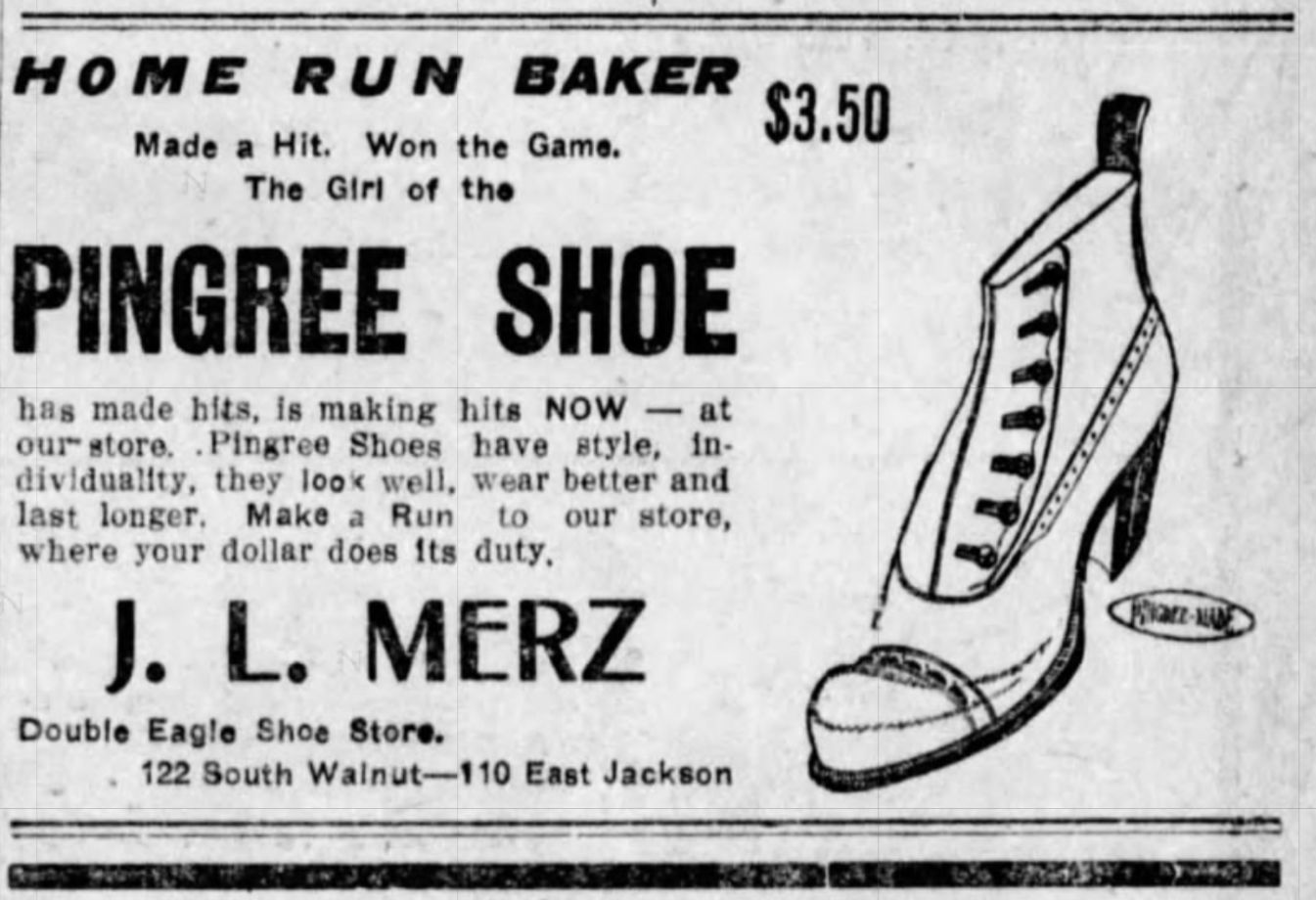

Photographs of Baker were printed with "Home Run Baker" captions underneath. An advertisement for women's shoes in Indiana's Muncie Evening Press even invoked Baker's name:

"Home Run Baker -- Made a Hit. Won the Game," proclaimed the ad for J.L. Merz's Double Eagle Shoe Store. "The Girl of the PINGREE SHOE has made hits, is making hits NOW -- at our store."

The name sticks

The A's won the World Series in six games, and Baker's heroics made him Home Run Baker forever.

In the days and weeks following the World Series homers, everyone sang Baker's praises.

His name was used for political humor.

- From the Springfield News-Leader: "Home-Run Baker is about the only man the Democrats could nominate for a place on the national ticket who would have a ghost of a chance of election, and if Baker has as much brains as he has ability to swat the ball, he is too wise to accept a gold brick like that."

- From the Galveston Daily News: "Perhaps the Philadelphians will now erect a monument to Home-Run Baker alongside the graven image of Hon. William Penn."

- From The Washington Post: "Looks as if Home Run Baker were the only man who could be elected mayor of Philadelphia without a bitter fight."

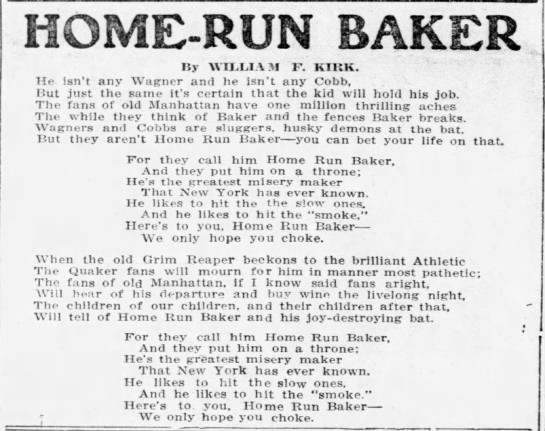

There were even poems written about him.

A fan submitted a limerick "dedicated to 'Home Run' Baker" and titled "Hurrah for Baker" to the Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin:

"There was a young man named Baker,

Who proved that he was no faker.

With a smile of his face

'Matty's' 'shoots' did he lace,

Three cheers for the home run Quaker."

And the great baseball writer William F. Kirk penned a poem titled "Home-Run Baker."

On the field, Baker would go on to lead the league in home runs for four straight years, hitting 11 in 1911, 10 in 1912, 12 in 1913 and nine in 1914. Over that span, Baker's 42 home runs dwarfed the next-closest American League total, Sam Crawford's 28.

So, once he had the nickname Home Run, Baker lived up to it, at least in comparison to the players of his own era. He was one of the earliest faces of the home run before it became ubiquitous in the decades that followed.

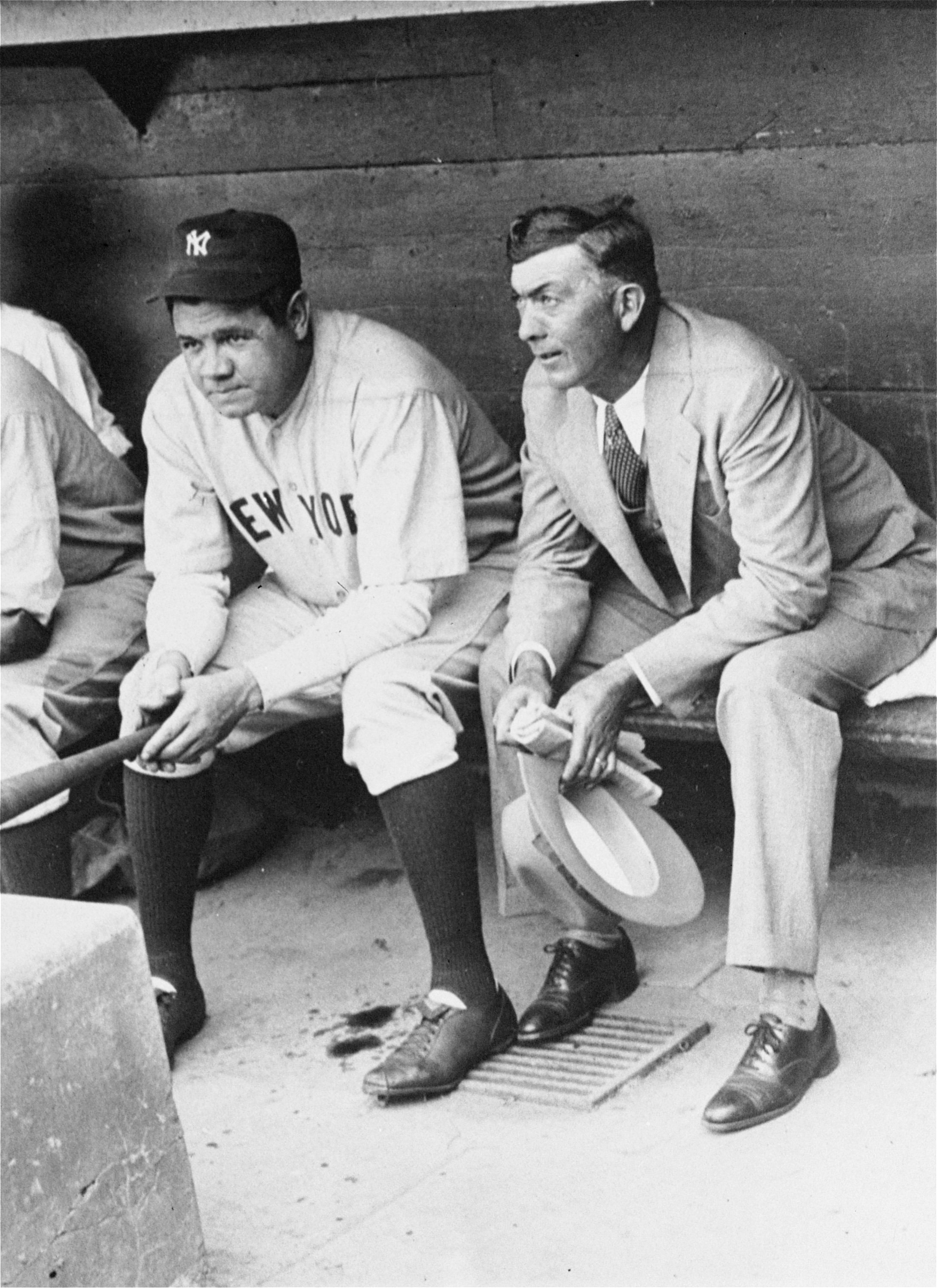

After helping the Athletics win a third World Series title in 1913 -- with one more home run in that Fall Classic -- Baker had his contract sold by Mack to the Yankees, where he spent the latter part of his career, hitting double-digit home runs twice more. He was a part of the original Murderers' Row -- though the term became famous through the Ruth and Gehrig-led teams of the late 1920s, it was first used for the Yankees lineup in 1918, before Ruth arrived.

Baker played his final two seasons alongside Ruth in 1921 and '22. Home Run Baker watched as the Great Bambino became the first great home run king as we know it today, and drove the sport into the Live Ball Era. But Baker is still the one who bears the Home Run name.