"You can only imagine," Mesa historian and author Jay Mark says. "There's this two-way highway in the 1930s and 40s, no lights out there, flat desert. And this big neon sign. You would've seen this thing for miles."

---------

If you're a baseball fan, you probably know that Spring Training takes place in either Florida or Arizona. It's been that way for nearly 100 years. Teams flocked to Florida first, around 1920, because the state wanted the business and tourism -- and promised to pay player expenses.

But what about Arizona? How did teams wind up traveling up to 2,000 miles west every year?

That story is a little more unusual.

Bill Veeck bought the Cleveland Indians in 1946 and decided the team should train there -- it was closer to his Tucson ranch and, upon signing the American League's first black player Larry Doby, he refused to subject the slugger to the harsher cruelties of the Jim Crow South.

But that was only one club. There was no league. Veeck's Indians had nobody to play.

That's where an old, roadside Mesa motel comes into the picture.

When local entrepreneurs Ted and Alice Sliger bought a plot on East Main Street in 1936, it wasn't supposed to be a motel. It was where they lived, it was a gas station, it was a gift shop and, most notably, it was a place for Ted to display his ginormous taxidermy collection. It served as a stopping-off point for weary travelers road-tripping along federal highways 60 and 70.

And then, in 1939, the Sligers decided to dig a well on the property so they didn't have to trudge barrels of fresh water from downtown Mesa every couple weeks. That's when everything changed.

"[Ted] got down about 300 feet and lo and behold, he discovered water," Mark says. "Unfortunately, it was about 113 degrees and full of minerals."

The Sligers had found a bubbling hot spring in their backyard. Although they couldn't drink it, this discovery, as you may have guessed, would end up being very good for business. A motel and spa were built and the Buckhorn Baths were born.

Tourism to the 15-acre site picked up during the war years in the early 1940s -- soldiers from nearby military bases were frequent visitors. And, eventually, word about this magical, healing mineral water got around to New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham. Stoneham already had reasons to move his team's preseason to Arizona: He had a winter home in the area, Veeck had been pleading with him to give the Indians someone to play against and savvy businessmen like Dwight Patterson (sometimes referred to as The Father of the Cactus League) had been working hard to recruit more clubs out west.

But what ultimately convinced Stoneham was the healing powers of the Buckhorn springs.

"Somewhere along the way, [Stoneham] had gone out to the Buckhorn and used the baths," Mark said. "He was very impressed by what he saw and experienced at the Buckhorn. He even got to know Ted and Alice very well. He decided to have his teams practice in Arizona in 1947 and bring his better players out a week or two ahead of time to the Buckhorn to get all that kind of treatment and get them into better shape."

And thus began the Buckhorn's decades-long relationship with baseball. The Giants stayed there for 25 years, starting in '47 and overlapping with their move from New York to San Francisco.

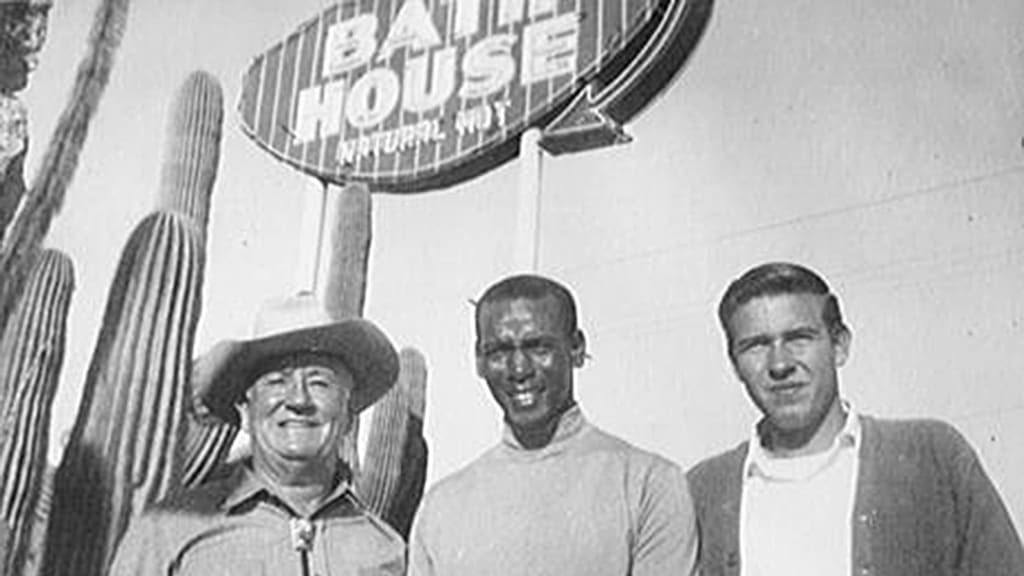

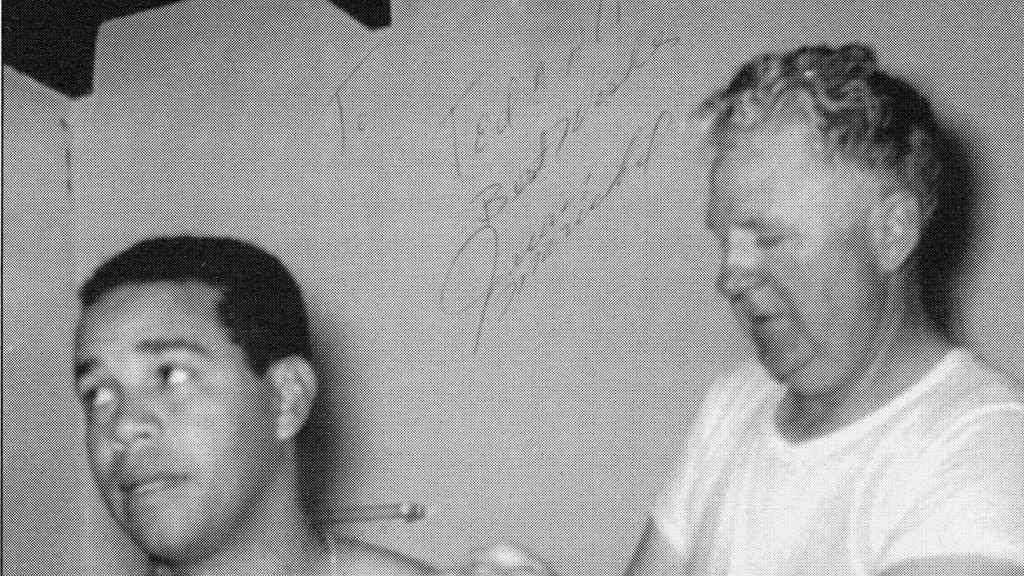

The Cubs, who had spent Spring Training on Catalina Island for 30 years, followed a few years later in 1951. They played their games in Mesa and also utilized the Buckhorn (team management had been looking for "healthful clean fun a small city can offer," and they had found it). Billy Williams was a frequent partaker of the spas. Here's Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks, with Ted Sliger and Ted Sliger Jr.

The Orioles would move out to Yuma in '54 and the Cactus League was officially born -- with the Buckhorn serving as its central hub.

"The Buckhorn itself became a celebrity," Mark said. "Not only athletes, but Hollywood people stayed there. President Truman's daughter had health issues and she stayed at the Buckhorn for three months. This became a very famous, popular, well-known place."

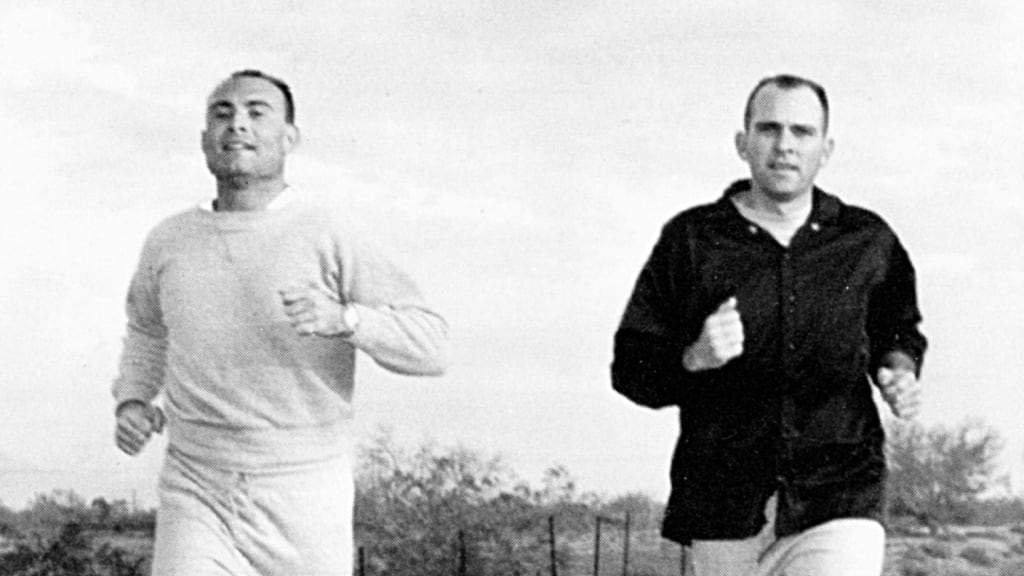

But mostly, it was a home for ballplayers -- predominantly the Giants. This bustling oasis of Hall of Famers in the middle of nowhere. Working out, eating and getting into game shape. Tourists would spot players having a catch on property or, you know, going for a casual morning jog through the desert.

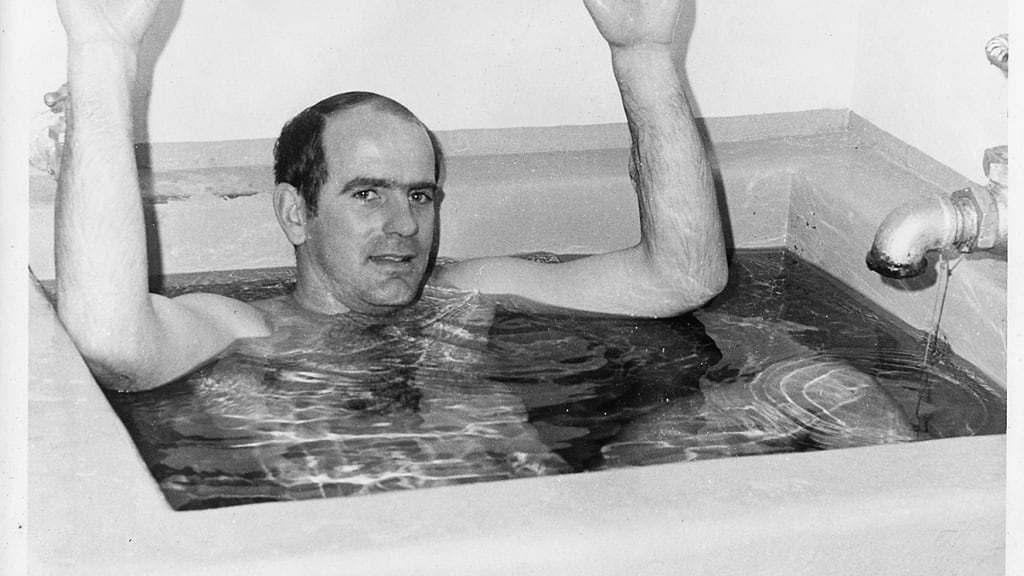

Ty Cobb, Ted Williams, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, Joe DiMaggio, Mel Ott and Willie Mays were just some of the names who came through Buckhorn over the years. Here's Giants ace Gaylord Perry -- a frequent visitor and dear friend of Alice Sliger -- soaking up some suds.

"[Alice] always had a welcome smile on her face and would always talk about the events of the day," Perry said. "She really loved the place."

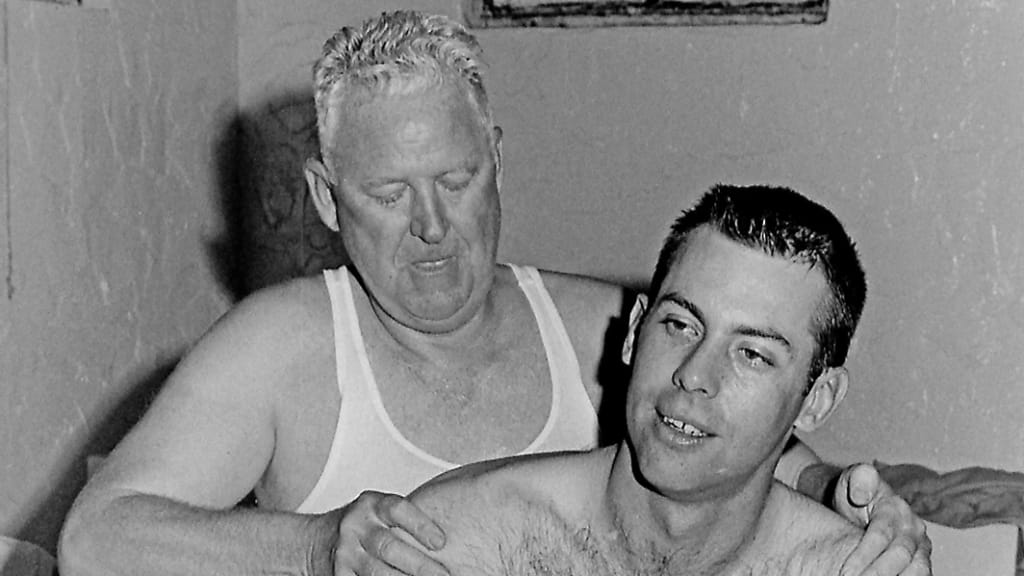

Here's former Giants All-Star and frequent hit-by-pitch artist Ron Hunt healing his body with a massage.

And 10-time All-Star Marichal -- warming up that golden arm.

Did the springs actually work in curing players' ills? According to the New York Daily Mirror, yes, yes they did.

"Effervescent players bounce around [Phoenix] Municipal Stadium as though they're fed on ginger, paprika, horse radish and various other forms of spicy vitamins."

It was a regular fountain of youth. There were claims that Giants outfielder Don Mueller healed his ankle sprain in the baths. Again, from the Daily Mirror.

"Many a layman who had grown flabby and had lost his bounce, checked in at the Buckhorn Baths and emerged a couple of weeks later, asking for a baseball bat."

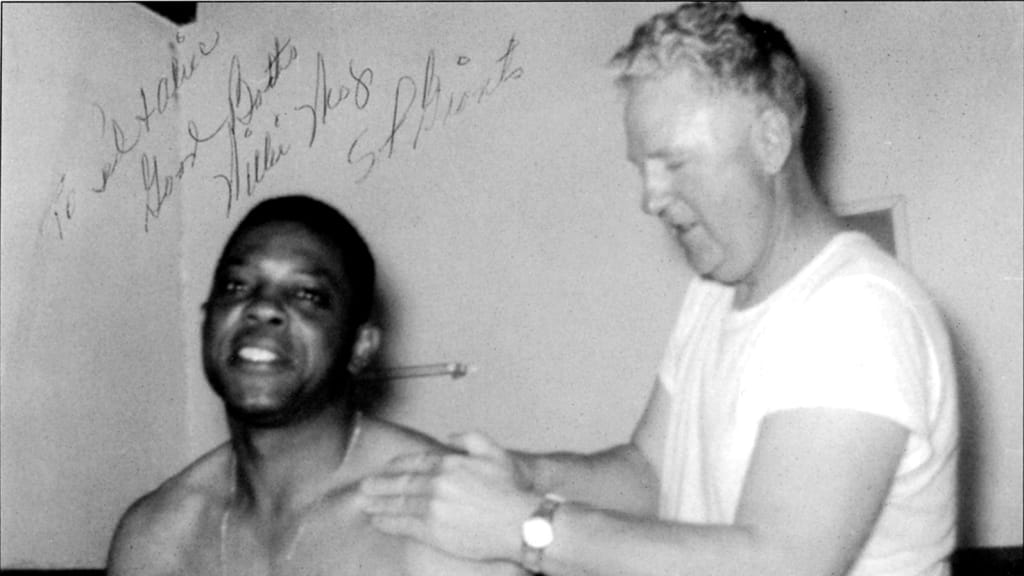

The Giants even credited their stays with helping the team win the 1954 World Series. Here's a signed photo from Mays, MVP in '54, thanking Ted and Alice for the "Good baths."

More than a place of healing, though, the Buckhorn was a place ballplayers could hang out, relax and be themselves. Even in a mostly-segregated Arizona, Mark says the motel provided an exception: "This is during an era of segregation, when the few black players who were playing at the time often had to stay in separate facilities. That was never the case at the Buckhorn. Willie Mays and other African-American players stayed there along with their fellow Anglo players."

The Sligers would also hold giant barbecues for players and their families (one was said to have more than 4,000 attendees; the town of Mesa had about 4,000 total people). Large welcome signs greeted them upon their arrival. It was a home away from home, with the Sligers and the rest of the staff serving as players' adopted parents.

"These were guys at their leisure," Mark says. "In sweatshirts and shorts, no uniforms, way out in the desert ... The teams and guests were treated really well."

Over time, with new team management and ever-changing Spring Training homes, the Buckhorn became less and less of a baseball hotspot. Ted Sliger died in 1984, the baths ceased operations in the late 1990s and the motel finally shuttered in the late 2000s. Alice, who died at the ripe old age of 103 in 2010 (how about those wellness springs, huh?), managed the property herself after her husband's passing. Players like Perry flocked to her funeral, speaking fondly of the memories and hospitality that little corner of Mesa, Ariz., showed for so many years.

Now listed on the National Registry of Historic Places, the buildings have deteriorated quite a bit since their heyday. But new owners are trying to restore the property -- there's talk of adding a micro-brewery, restaurants and giving the interiors and exteriors a fresh new look. The Mesa Preservation Society is keeping a close eye on the land and, who knows, with that magic water still pumping through the pipes, maybe the Buckhorn Baths can have a second life as a Spring Training mecca once again.