From the moment it became clear that the 2020 Major League season would be played with no fans in the stands, we knew that the home-field experience would be very different. Visiting outfielders wouldn't have to contend with grabby hands on balls near the fence. Pitchers in a tight spot wouldn't have to deal with 35,000 screaming voices. We knew it was going to be different. We just didn't know how different.

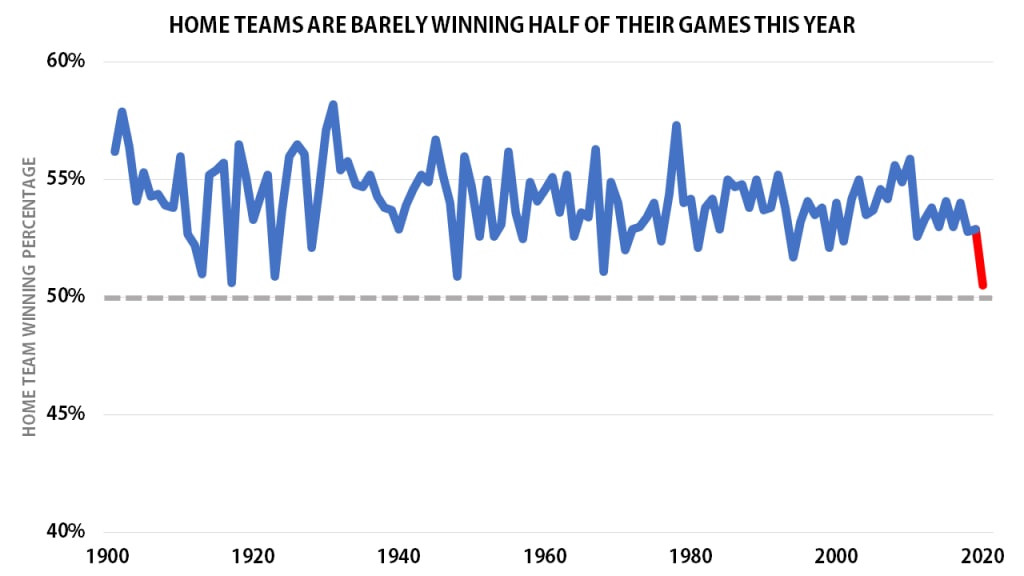

Well, how's this for different? More than a third of the way through this shortened season, home teams are winning just 50.5% of the games they've played.

That would be the lowest rate ... well ... ever.

Home teams, through Sunday's games, have gone 155-152 to start the year. (That they're above water at all is somewhat thanks to the efforts of the Yankees, who have gone 9-0 at Yankee Stadium so far -- the one loss was as the "home" team at Citizens Bank Park.) We're this close to seeing home teams being a losing group as a whole, and it's close enough that we might actually get there at the end of any upcoming day.

This is notable because home-field advantage, while less of a factor in baseball than it is in other sports, has been remarkably stable over the years. Pick any start year you like; it's always at or near a .540 winning percentage.

Home team winning percentage, MLB

Since 1901 (Birth of the AL): .541

Since 1920 (Live Ball Era): .541

Since 1947 (Integration): .538

Since 1969 (Divisional play): .538

Since 1998 (30-team era): .536

Since 2008 (Pitch-tracking era): .538

It gets high sometimes, sure; in 1930, it was .571. It gets low sometimes, sure; in 1948, it was .509. But in general, this hasn't changed all that much. It fluctuates in minor ways around that .540 mark.

So ... what is it? What's making home field less advantageous -- or, perhaps, making visiting teams better-equipped?

Maybe it's a fluke

It's 2020 and there is a global pandemic, so "maybe it's a weird fluke" is always, always an option.

Remember, several teams have played 23 games, but the Cardinals have played only eight heading into Monday. A week ago, everyone was panicking about the historic lack of offense after the Majors posted paltry OPS marks of .712 and .702 in the first two weeks, right before they put up a .797 over the last week. Charlie Blackmon is still hitting .446. The Blue Jays have played home games in Buffalo, N.Y., and batted last in Washington, D.C., but will not set foot in Toronto. The Cubs are batting first at their home park against the Cardinals for the first time since 1898. You get the point.

Literally any outcome is on the table in this unique season. (Seriously, imagine at any point thinking the Orioles would have more wins than the Astros.) So if this all sorts itself out by the end of August, don't be terribly surprised.

Then again, "the lowest home winning percentage ever" is still a headline that draws attention. So how often does this stretch happen? Does it ever? Entering Monday, there had been 307 games played. With the help of MLB.com's Senior Data Architect Tom Tango, we looked back at all 307-game stretches from 2019, and found that home teams were under .500 in those spans about 5% of the time. So while rare, it's not unprecedented.

Even so, it's happening so far. Why?

Maybe it's the strike zone

Though umpires are often the target of fan ire, they by and large do an outstanding job at a nearly impossible task. (Think about how difficult it's become for hitters to make contact in the face of increasing velocity and more breaking pitches than ever. Now consider that for strike-calling, especially with every catcher working on framing. It's a really hard job many fans don't respect enough.)

Still, they're human beings, and there's been a documented effect that a large part of home-field advantage lies in the strike zone. In 2017, FanGraphs wrote about a study from the 2011 book "Scorecasting" by Tobias Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim, who wrote:

"In baseball, it turns out that the most significant difference between home and away teams is that the home teams strike out less and walk more -- a lot more -- per plate appearance than road teams."

That's still true. Just look at 2020 to date.

Home batters: 9.4% walk rate, 22.7% strikeout rate

Road batters: 8.8% walk rate, 23.9% strikeout rate

The FanGraphs study later argued that the effects of the zone at home "accounts for roughly 70 percent of home-field advantage."

We'll get back to that in a second, but remember, too, that baseball is not the only sport that has attempted to come back without fans.

In June, ESPN reported that in early in the return of the German Bundeliga soccer league, which also came back without fans, home teams had won fewer games and scored fewer goals compared to pre-pandemic play. On July 1, The New York Times followed up and noted that "the number of home victories slipped by 10 percentage points." Even more specifically, the referees acted differently. "Away teams are shown 2.28 yellow cards per game with fans and only 1.90 without," wrote the Guardian in June.

Baseball doesn't have yellow cards, but they do have called strikes.

“On average, home field made a called strike 1.7% more likely last year, all other things being equal,” Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus told the Ringer just before the season began. While Judge's detailed method correctly attempts to adjust for the identity of the catcher, umpire and other factors, we can attempt to simplify and see if anything's noticeably different.

To that end, we looked back to 2008, focusing on non-swings at the edges of the strike zone, in an attempt to see how often those pitches were called strikes.

Every year, as the previous studies indicated, home teams got slightly more of those calls. In 2010, for example, visiting batters had a 45.1% called strike rate against them on the edges, while home batters had a 44.3% mark, a difference of 0.8%. (Or a little more than 300 strikes.) In 2015, visiting hitters saw a 47.1% called strike rate, a tick more than the 46% from home batters. Each year from 2008-19, this effect held true, with an average of 0.8%.

Except this year, that is. Visiting hitters are getting called strikes on the edges against them 48.9% of the time. Home hitters are seeing more: 49.2% of the time. It's not a huge gap at all, but it's the first time on record that home hitters aren't getting a slight advantage.

It's a similar story on two strikes, too, where for the first time, home hitters (33.5% called strike rate on the edges) are getting rung up more than road hitters (32.5%).

The effect is unconscious, surely, and not even that large, but it does match what we saw reported from the European soccer league. Small samples? Sure. But that would be some sort of coincidence to see this in European soccer and American baseball at the same time, wouldn't it? Fans, it seem, matter.

Maybe it's just the National League

No, hold up here: It's definitely the National League.

The AL has seen a .522 home winning percentage, which is up a little from last year (.511), and down only slightly from the .534 they'd seen from 2010-19. The Yankees are 9-0 at home, while the A's are 9-3 and the Twins 9-2. On the other end, the Red Sox are 3-9 and the White Sox are 3-8. This is mostly normal.

But the NL? National League teams are winning just 48.6% of their games at home, which is the lowest for any league in a season ever -- and down enormously from their .548 last year.

Now, this is where 2020 insanity factors in, because the Marlins and Cardinals, the two teams affected most by COVID-19, have played a total of six home games. But that won't explain this big difference in offense, either.

NL teams, home: .766 OPS

NL teams, road: .701 OPS

Meanwhile, AL teams have shown almost no home/road split, posting a .737 OPS at home and .730 on the road. This isn't because of the DH, which can be used in all games. It's not because of Coors Field, because road teams get to hit there, too. It is, to be honest, not totally clear what's causing this.

Maybe it's the lack of travel

Remember, the regionalized schedule, where teams stick to East / Central / West without much regard for AL and NL, is a big change this year. You can see what the travel looks like on this map. (While it still shows Toronto instead of Buffalo for the Blue Jays, the two cities are close enough that it won't make much difference.)

That's easily sectioned out, isn't it? While Seattle still has to make that trip to Dallas and Houston, the Central teams barely have to go anywhere at all. The Brewers, for example, travel only 3,962 miles, and not all of that is by plane -- trips to play the White Sox and Cubs in Chicago are easily done by bus. The Yankees may have to fly to Georgia and Florida, but they're very close to the Mets, Phillies, Red Sox, Nationals and Orioles.

Now, compare that to the North American portion of the 2019 schedule. So, so many cross-country flights.

Obviously, the season isn't as long this year, but it's still stunning to see the difference between the Brewers barely traveling 4,000 miles this year, and the Mariners traveling more than 46,000 miles last year.

Let's go back to that 2017 FanGraphs article for a moment. Travis Sawchik spoke to Will Ahmed, the founder of a wearable technology company called Whoop, who explained some of his findings about rest.

“We found that athletes, when traveling, on average got an hour less sleep than athletes that did not travel,” Ahmed said. “An hour less in bed, 45 minutes less sleep. That’s about 10% lower recovery. Conventional wisdom says the home team wins because they have their fans supporting them or they are playing in a familiar park. The study suggests the home team may win because they are better recovered and better well rested.”

We would certainly not describe the 2020 season as restful in any way, especially for a team like St. Louis that will be forced to endure doubleheader after doubleheader in an attempt to make up for missed time. Yet one thing that's clear is that players are spending less time in the air and less time traveling around the country. Might that be a factor? It's difficult to prove, but can't be ruled out.

So what, of all these reasons, is it? As usual, it's probably a little of everything, with a strong nod towards "2020 is ridiculous and the pendulum could switch back at any moment."

Mike Petriello is a stats analyst for MLB.com, focusing on Statcast and Baseball Savant, and is also a contributor to MLB Network.