Like the pitch, the knuckleball factory is mysterious. Fleeting, hard to track down.

Even when you have its location – about 15 minutes southeast of L.A.’s Redondo coast in Torrance, Calif. – you’ll start questioning yourself during the drive: “Wait, this can’t be the way? Do I have the right address? Why did I ever leave the beach?”

You’ll make a turn into what looks like an entrance for a hospital. You’ll drive by rows of medical supply buildings, a fence store and an oriental rug shop.

You might just be getting more and more lost.

But then, when your GPS stops you where the facility is supposed to be, you see a man holding a baseball and holding court amongst a group of bystanders in a parking lot. He’s pressing the top of the ball with two fingers, talking fast and waving his other arm animatedly in front of his face. He’s a bit older but he still looks familiar, not unlike he did throwing his final buckling, knuckling Major League pitch 30 years ago.

“Let’s get to it,” Charlie Hough tells us once we get out of the car, taking a swig of his water bottle of apple cider vinegar. “I only have a few minutes.”

“A Pure Freak of Imagination”

The origins of the knuckleball are foggy.

Some say a pitcher named Toad Ramsey invented it after slicing his hand laying bricks -- only being able to “push” balls across the plate with two fingers. Others say it was conjured up by famed White Sox junkballer Eddie Cicotte, who called it “a pure freak of imagination.” Still others claim it was some pitcher in the short-lived Blue Ridge League during the early 1900s. He taught it to someone who taught it to someone else who taught it to someone else.

Either way, the intent is mostly the same: To produce a slow, hovering pitch with little to no spin.

“A knuckleball is generally held with two fingernails, and the job of the pitcher is to throw the ball out of his hand with very little rotation,” Chris Nowlin, owner of Knuckleball Nation, said. “If there’s any rotation, you want it spinning forward so it bites into the wind. The air flows over the seams and creates all sorts of turbulence, pushes the ball around maybe three or four times on the way to the plate.”

If that sounds confusing and looks hard to do, it is. The pitch’s trajectory mostly depends on the air rushing around it, so nobody – not the pitcher, the catcher, the batter, the umpire – really knows where it’s going to go. Nowlin says the difference between a good and bad one is about two millimeters.

There can be 10 strikeouts during one start and 10 walks during the next. There can be five passed balls in one inning. There are specific catchers signed to catch the fuzzball. Hall of Fame hitter Willie Stargell maybe put it best:

“Throwing a knuckleball for a strike is like throwing a butterfly with hiccups across the street into your neighbor's mailbox.”

Even Hough, who won 216 MLB games using the knuckleball, didn’t know where it would go most of the time.

“I had two seams hitting the wind and it could go either way,” the 76-year-old Hough, who discovered the pitch as a teenager after his arm blew out, told me. “I learned it and spent the next 25 years trying to get it over.”

All of that, of course, would also make it hard to teach. But that’s what most intrigued Chris Nowlin.

The Beginnings of Knuckleball Nation

Nowlin grew up outside of Boston and went to about a dozen Red Sox games per year as a kid. During one of those nights at Fenway Park, running around with his friends, he was witness to a performance by one of the game’s great knuckleballers: the late Tim Wakefield. The way he describes the moment feels like a scene from a movie.

"I ended up right behind the backstop and Wakefield was taking a no-hitter into the seventh," Nowlin said. "And it was like quintessential Fenway Park. It was hazy, Green Monster in the background, Citgo sign. And he was just throwing these balls that didn’t rotate at all. I was looking around like, ‘Is this real? Are we all watching the same thing?’ I was looking at the adults for reassurance: ‘Is this … can he do that?’ I’ve been obsessed with it ever since.”

Alas, Nowlin was an all-year basketball player and didn’t play baseball in high school or college. He did still practice the pitch during downtime at school – tossing tennis balls against sheds and floating baseballs into a sock net. Eventually, during his senior year at UMass, his friends caught him throwing the pitch, thought it had potential and suggested he go to a nearby open tryout for the Reds.

Using a borrowed glove and cleats and stacked up next to guys throwing 95-plus, Nowlin stepped up to the mound for his showcase in front of a Reds cross-checker. He struck out three straight guys on four pitches each. The next three didn’t get anything out of the infield.

The Reds scout was impressed. He pulled Nowlin into his office and said he’d recommend that the Reds select him with their last pick in the Draft that year, 2004, back when each team had 50 picks and often spent the latest rounds taking fliers. Unfortunately, the scout was ultimately let go and his recommendation was never followed. But he did get across some parting words for Nowlin after he graduated from UMass:

“You have this really strange gift -- chase it.”

Nowlin took that advice, moving out west with dreams of becoming a pro knuckleball pitcher in the independent leagues or, really, any league that would take him. Eventually, he ran into a “knuckleball scouting expert” during a tryout at Long Beach State. That “expert” was Hough.

“Here’s my phone number. Call me in two weeks. You’re horse---- with potential.”

Nowlin began training with Hough at Cypress Community College around 2006-07 alongside R.A. Dickey – a former big league fireballer who was attempting to come back as a knuckleballer (and would eventually win the NL Cy Young Award). Wakefield would pop in. Hall of Fame knuckler Phil Niekro was involved.

Nowlin honed his unique skill and used it to pitch for years in various indy leagues and even across the globe in Australia. Soon, though, he was a broke ballplayer living in Vegas. He needed some source of income.

That’s when he came up with Knuckleball Nation.

“I was selling this really rudimentary video for 50 bucks,” Nowlin said. “It started selling. Then I put out the word for a clinic to see if that would work. Fifteen people showed up from all over the country.”

Fifteen people in Vegas turned into clinics all over the U.S. and in places like Taiwan and Japan.

There have been guest appearances by Dickey at clinics in Tennessee. Former Boston knuckleballer Steven Wright has dropped in to help out. Hough, of course, has made many visits to the Knuckleball Nation factory in Torrance. And Niekro was a father figure before his passing in 2020.

"I'm pretty sure my last clinic with Phil was in late 2020 before the world went to hell," Nowlin recalled. "He put his hand on my shoulder, looked me square in the eye and said, 'I love you.'"

The Torrance facility is officially named the Beimel Athletic Facility -- owned by former big league pitcher Joe Beimel. But among college or pro pitchers trying to up their speeds and increase their spin rates (Lucas Giolito and Robert Gsellman have been guests), there’s a small contingent of high school, college, pro and even Little League players trying to lower their speeds and decrease their spin rates. They’re trying to make the ball float. They’re attempting to master the art of the knuckleball.

The Disciples

Jake Williams, from Madison, Wis., first learned the pitch at GRB Academy. He was an infielder but was spellbound by how the ball moved when another player threw the pitch during a game of catch.

“I actually looked up a video on YouTube on how to grip it and I ran into a video on how R.A. Dickey does it,” Williams told me. “And that’s actually how I grip it today.”

The 21-year-old met Nowlin at a clinic in Vegas a few years ago and has another year of college eligibility – hoping to sign on somewhere, with some coach who believes in the effectiveness of the pitch.

Ben Gaffney started throwing the butterfly ball at 8 years old. His older brother threw it, so why couldn’t he?

“I’ve improved drastically over the last two years most from Charlie Hough and these clinics,” Gaffney, a high school sophomore out of New Jersey, said. “I think a good knuckleball is pretty much unhittable. When you throw it for a strike, nobody can hit it. The problem is just throwing it for a strike.”

Gaffney hopes the pitch gets him recruited to a good college, and from there, he’ll see where the knuckler takes him.

“I’d say the best I pitched with the knuckleball was last summer,” Beau Huckemeyer, another sophomore from Colorado, said. “Complete game, 70 pitches. Just dropping. Fooling everybody.”

He credits Nowlin and his clinics for making his pitch better and sticking with it through good times and bad.

At 11 years old, Neeko Villarreal is the youngest of Nowlin’s students. He throws the pitch for both his local Little League and travel teams. It’s a tough pitch to handle at that age, when most kids are just figuring out how to hit any pitch at all.

“It’s fun,” Villarreal said. “Sometimes you see them out in front, reaching for it, swinging under it.”

In MLB The Show, Neeko and his friends love playing as Matt Waldron, the only semi-knuckleballer currently in the Majors. They love how the ball moves all around the screen.

The Position Player Making a Knuckleball Comeback

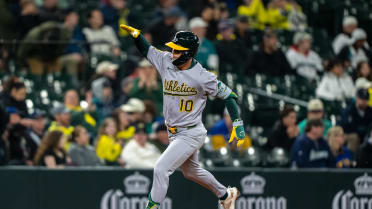

Alex Blandino thought his baseball career was over.

He had played three years as a part-time utility man for the Reds from 2018-21. He played in the World Baseball Classic for Team Nicaragua in February 2023. But nobody was calling him to play again anywhere in the Majors for that season.

“I bought my first house; your priorities change,” Blandino told me. “You have to provide for your family.”

But at just 30 years old, the itch to play the game he had played his whole life was still there. So, he began going to a pitching facility near his house in Southern California to toss with friend/former big league pitcher Erik Goeddel. Soon, he started throwing knuckleballs. He’d thrown them as a pitcher in high school, and when he had a chance to take the mound as a position player in the Majors, he never missed an opportunity to throw them again. They were pretty good, and, well, it was entertaining.

A man working at the facility noticed Blandino throwing the pitch from across the room. The facility Blandino had been throwing at? The Joe Beimel facility. The man? Chris Nowlin.

“He came over and his eyes were, like, lit up,” Blandino remembered. “He’s like, ‘This is very good.’ I think I shocked him.”

“I see people throwing knuckleballs all the time,” Nowlin said. “I walked over there and was like, ‘Ohh, ohh, OK.”

Blandino and Nowlin worked together for months, improving the positioning, rotation and consistency of the pitch. Eventually, Nowlin deemed Blandino ready to throw in front of Hough, the elder knuckleball statesman who could end a knuckleballer's dream with one shake of his head.

“I threw, like, an 80-pitch bullpen for him and Charlie was like, ‘This is legitimately good,’” Blandino said. “I can think it’s good, but Charlie – who’s been doing this for 20 years – knows what it takes.”

Blandino took that vote of confidence as a sign he should maybe, actually, pursue the wild idea that he should be a knuckleball pitcher. It was also September 2023 at this point, and his fiancée was wondering what he was doing with his life.

So, he called up Reds Assistant GM Jeff Graupe and asked, especially in this climate of high-velocity pitching, would they ever be interested in a knuckleballer?

“He said, ‘Well, is it good?’” Blandino said, laughing. “He’s like, ‘Why don’t you come out and throw for us?’”

Blandino traveled to the Reds' Spring Training complex in Arizona and tested out his new pitch in simulated and exhibition games. Management liked what it saw and offered the position-player-turned-pitcher a Minor League contract for the 2024 season.

“It was wild,” Blandino recalled. “It just kind of validated everything I’d been doing.”

The Reds are looking for the right level and opportunity to place their newly acquired weapon, but for now, they want him to throw as many knuckleballs as possible in games where balls and strikes don’t matter as much. That's advice Hough can agree with.

“I’ve seen [Blandino] throw a big league knuckleball … occasionally,” Hough said. “Which is the way it starts. That’s exactly the way I was only he’s got a much better arm than I had. We’ll see. It’s gonna take a lot of innings and a lot of patience.”

The Future of the Flutterball

That’s part of the problem with the knuckleball: It takes patience.

Patience from the pitcher trying to throw it. Patience from coaches sitting there in the dugout and waiting until it starts working. Patience from GMs upstairs. Patience from baseball, which, especially nowadays, has always been infatuated with athletes who can throw the fastest possible fastball. Waldron is the only knuckleballer in baseball this year and they’ve been as rare as ever over the last two decades.

"People are afraid of what they don't understand," Nowlin said. "But a well-thrown knuckleball is one of the best pitches in the game. It's completely unhittable. It's just scouts don't know what they're looking for, the metrics guys don't know how to measure it and front-office guys aren't willing to put their name on it."

But Hough, who stayed at the facility for about an hour helping knuckleball hopefuls (after saying he had only a few minutes), believes it can, once again, become part of the game.

“It would be nice -- I would love to see it,” Hough, currently the Dodgers' roving pitching coach, said. “I’ve shown it to a lot of kids. I’ve seen it work with Timmy Wakefield and R.A., and they were good. Right away. They were great.”

It’s an advantage in a starting rotation.

“How are you gonna prepare for a knuckleball?” Blandino said. “The unpredictability of it -- it breaks the game. In a game that’s so metrics-based: ‘He’s got 20 inches of ride on his fastball, his slider has 23 inches of horizontal, you need to tunnel this little one inch in the box.’ What’s your game plan for a knuckleball? It’s like, ‘Welp, go get ‘em.’”

And, most of all, it’s fun.

It creates characters like Hough and Wakefield and Hoyt Wilhelm who can pitch into their late 40s hurling this dipsy-divey bug. It makes some of the best hitters in the world say they'd "rather have their leg cut off” than take an at-bat against it. It radiates a sort of magic, during a warm summer night at Fenway Park, that can inspire kids like Nowlin to fall in love with the game, learn this crazy craft and spread their knowledge to anyone who thinks, "Hey, maybe I can make that ball dance, too?"

Main Illustration by Tom Forget

Matt Monagan is a writer for MLB.com.