Banned from the World Series? It almost happened ... to Wrigley Field

It was just after midnight when the final out was caught. The Cubs -- a franchise so long synonymous with day baseball -- celebrated their 108-years-in-the-making World Series glory not beneath the sun at iconic Wrigley Field but beneath the glow of Progressive Field’s distinctive “toothbrush lights.”

History was made at night. Such was bound to be the case when the Cubs finally killed the “Curse of the Billy Goat,” because Fall Classic games have long been a made-for-primetime television special.

History was also made on the road. In 2016, this was a matter of happenstance. Chicago had the superior regular-season record that year, but Cleveland was hosting Game 7 because of the American League’s victory in the All-Star Game (the final season in which this awkward arrangement was employed).

[A version of this story originally ran in November 2020.]

What few know is that, had the Cubs managed to make that history in 1985, not 2016, the long-anticipated final out still would have been recorded on the road, no matter which game they clinched the title. The Cubs could have been the “home” team in this ’85 scenario and, regardless, been playing in a ballpark other than Wrigley.

We’ll spare you the trouble of rummaging through the record books and go straight to the spoiler: The 1985 Cubs did not reach the World Series. Or the postseason. They went 77-84 and finished fourth in the National League East.

But because of their juxtaposition to a legitimately good Cubs club in 1984, and because of their own first-place standing as late as the morning of Father’s Day, the '85 Cubs created an almost unthinkable dialogue between their own front office and Major League Baseball. And had they not fallen victim to rotation injuries and a mammoth second-half slide, they could have made history of a very different sort, long before a global pandemic forced MLB to place the World Series in the protective wrap of a neutral site in Arlington, Texas:

The Cubs could have been the first homeless home team in World Series history.

* * * * *

“I played all my home games under one light, God’s light.” -- Ernie Banks, 2008

Ivy and infamy. For decades, the Cubs were known for day baseball and losing baseball. In 38 seasons from 1946 to 1983, they had just three second-place finishes, five third-place finishes and a whole lot of black-cat-quite-literally-crossing-your-path bad luck.

The awful outcomes weren’t entirely attributable to curses, coaching and club construction. It’s reasonable to speculate that the schedule had a little something to do with it, too. Wrigley Field was a source of both affection and affliction.

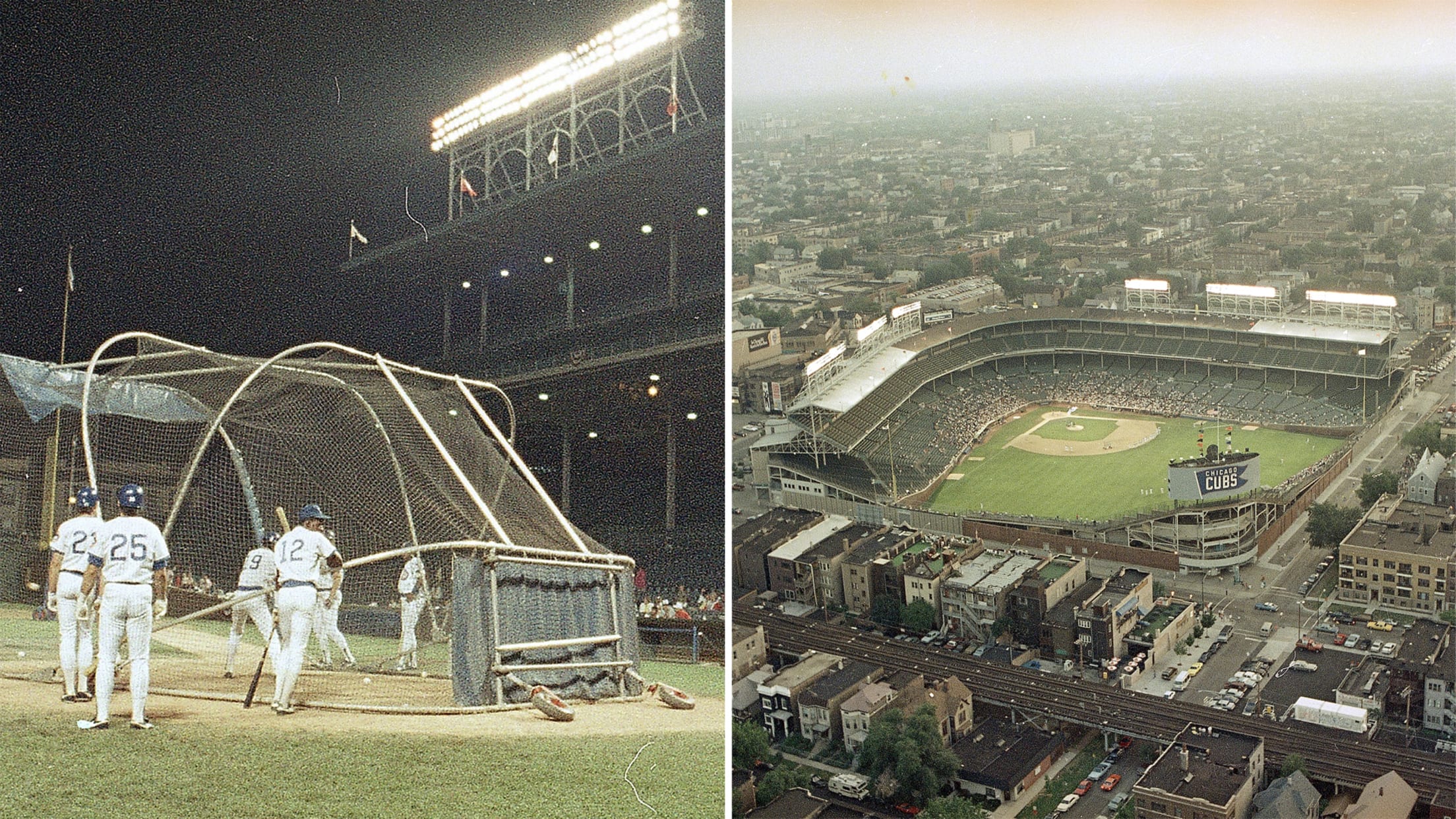

“The Friendly Confines” were lightless confines. Major League Baseball’s first night game was held in Cincinnati in 1935. The Cubs had plans to add lights for '42, but those plans were scuttled by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. By '45, when the Cubs reached the World Series, they were in a minority of unilluminated teams.

By 1948, they were the lone holdouts.

In clinging to a simpler past, the club refused to add lights that would allow them to play at night. While considered charming by purists, this was both delightfully out-of-step with the times and a step behind. Day baseball inspired possibly the greatest managerial rant of all-time (Lee Elia’s 1983 lament that “85 percent of the [expletive] world’s working, the other 15 come out here”).

But the clock and the heat took their toll on North Side teams, most notably the '69 club that collapsed in September.

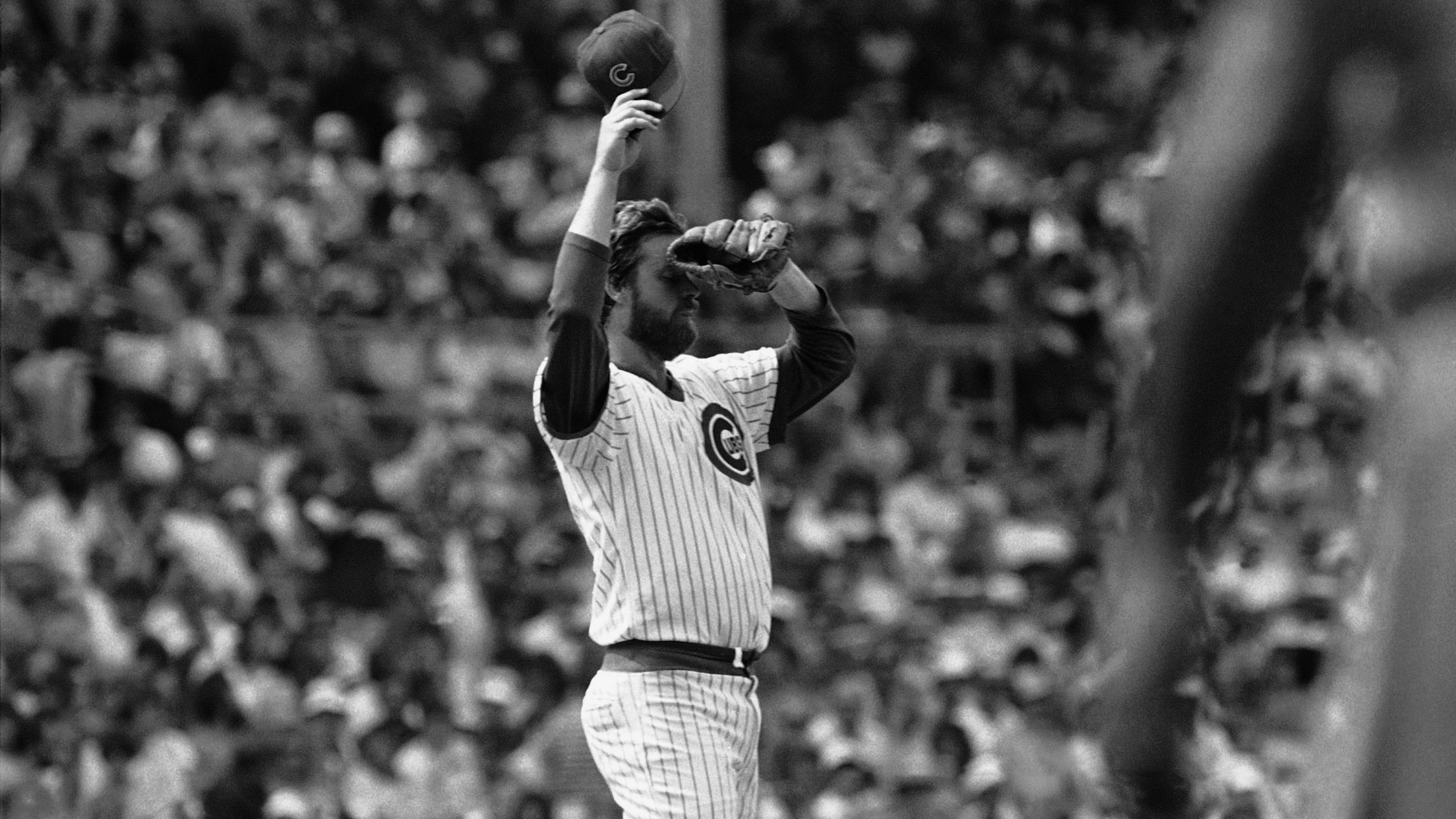

“For a family man, it was ideal,” former Cubs pitcher Rick Sutcliffe says of playing day games at Wrigley. “You get up in the morning, you take your kid to school, you play a game, you come home and have dinner with your family.

“But if I would throw a complete game at night at Dodger Stadium, I might lose anywhere from two to maybe four or five pounds. When I would pitch a typical complete game at Wrigley, I would lose anywhere from eight pounds to … I lost 14 pounds one time in a nine-inning game. I literally had to get IVs because of all the weight I lost.”

I lost 14 pounds one time in a nine-inning game [at Wrigley].

Rick Sutcliffe

It wasn’t until the 1981 sale of the Cubs from the Wrigley family to the Tribune Company that the attitude toward the team -- and the lights -- began to change. Merely selling the Wrigley Field experience was not enough. Tribune wanted to win games and build revenue.

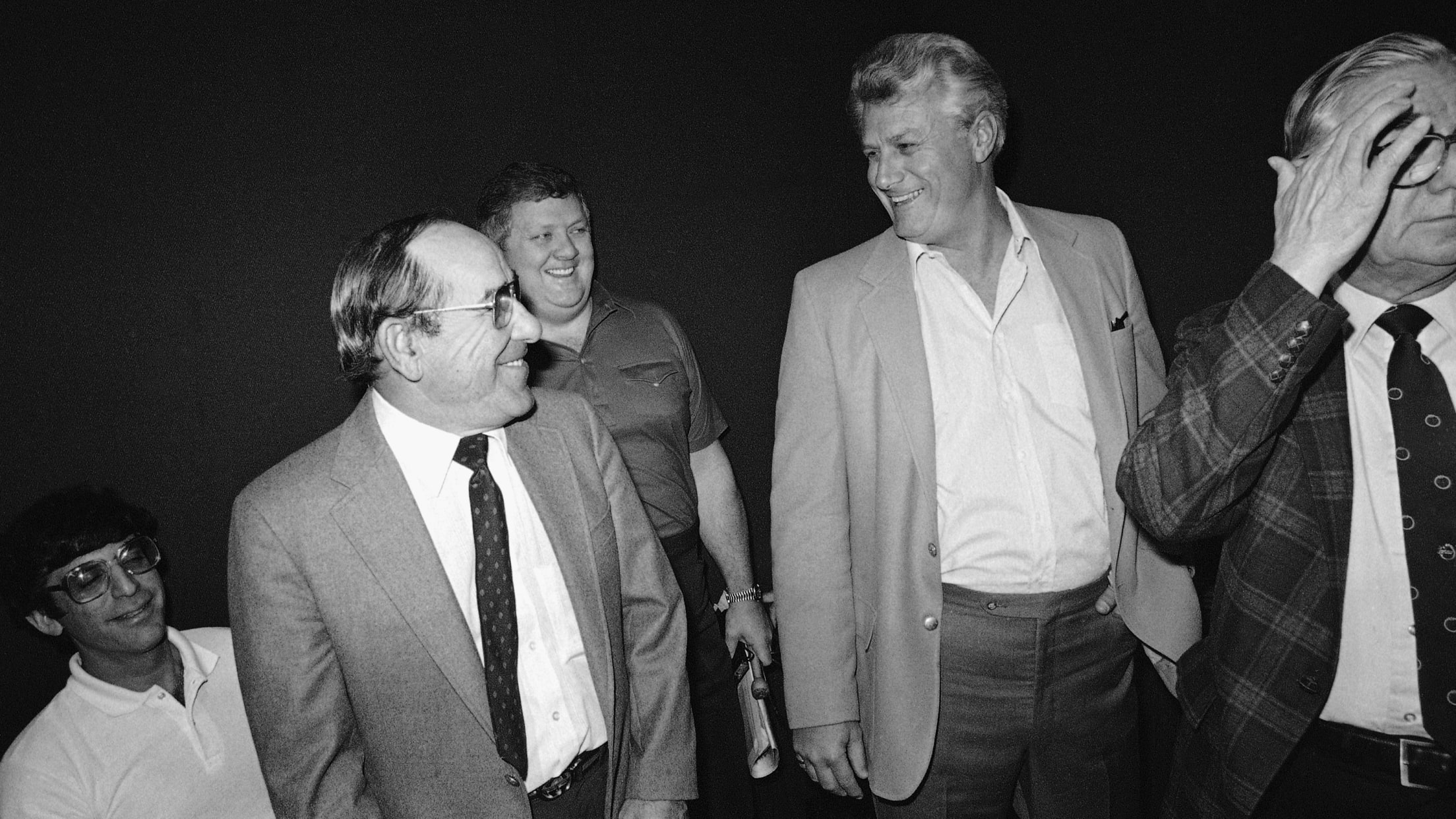

The first acquisition toward that end was the hiring of general manager Dallas Green away from the Phillies, where he had been the field manager in Philadelphia's 1980 run to the World Series title.

“[Green] had a presence,” says Bob Ibach, who was the Cubs’ director of public relations at the time. “He was like John Wayne. That guy walked in a room, and everybody turned their head. He had that shock of white hair, and he was a gunslinger.”

Under Green, the “lovable losers” schtick was no longer tolerated internally.

Neither was the lack of lights.

“As soon as Dallas got to town, he campaigned for lights,” says Ned Colletti, who, long before his tenure as Dodgers GM, worked in media relations for the Cubs. “Dallas was doing what he thought was right. And initially, his passion for building the franchise and making it competitive rankled a lot of people.”

Especially the residents of Wrigleyville.

* * * * *

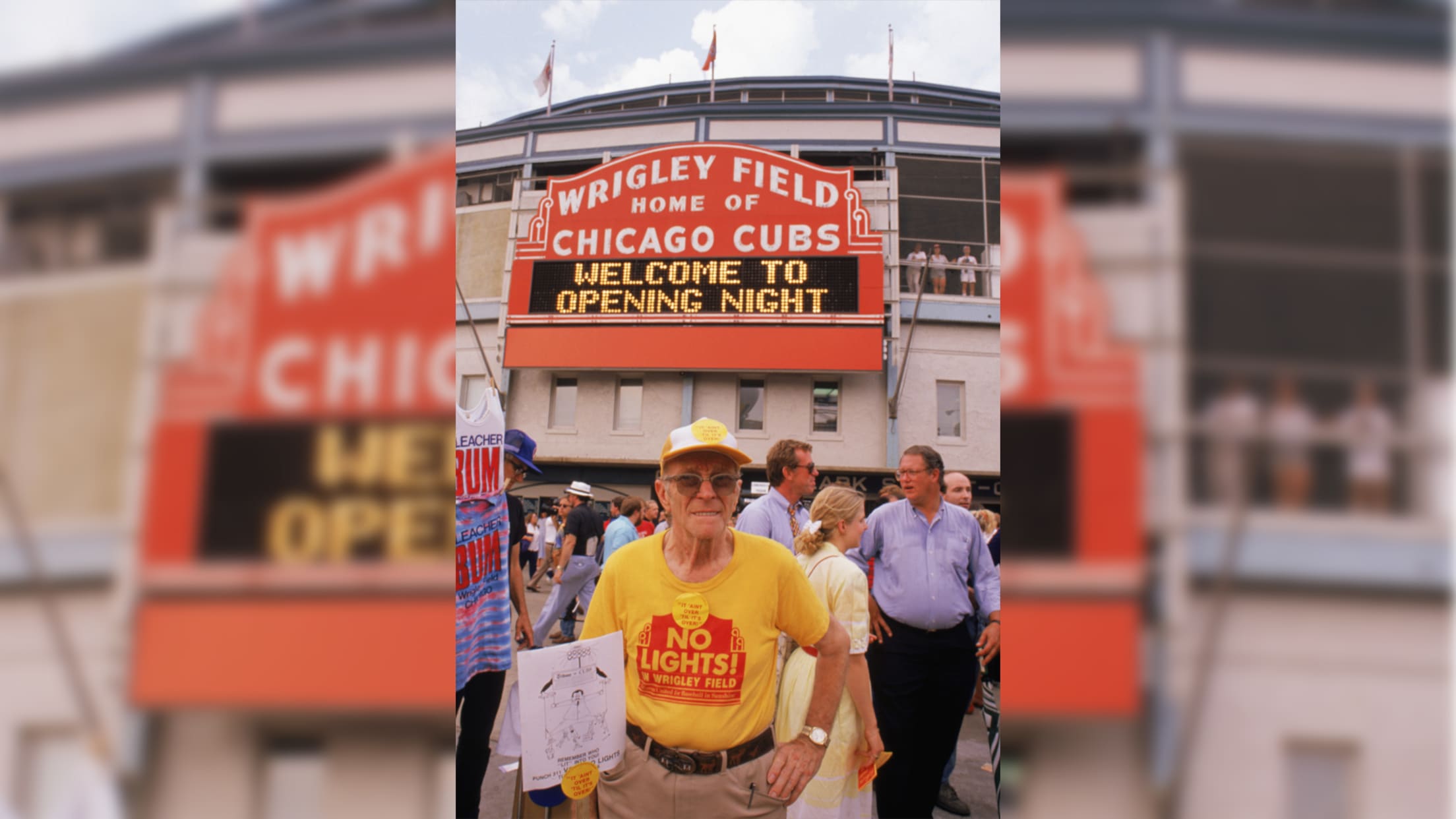

In the 1980s, it was the Cubs vs. the C.U.B.S. -- as in, Citizens United for Baseball in Sunshine. Representatives of the Wrigleyville neighborhood banded together to fight the Tribune Company at every turn in its plans to install lights at Wrigley. They were already irked about the parking problems, traffic and noise caused by 81 day games. They worried that rowdy, inebriated fans would cause even more havoc at night.

“They can play night ball,” C.U.B.S. member Charlotte Newfeld told an Illinois House committee in 1982, “but not in our neighborhood.”

Green’s cantankerous and coarse tone only emboldened the C.U.B.S., who would come to games wearing T-shirts that said, “No Lights in Wrigley Field” and stage rallies outside the ballpark. They were organized enough to get both the Illinois legislature and the Chicago City Council to effectively ban night games at Wrigley. And perhaps that’s how things would have remained for many more years if not for an interesting wrinkle.

The Cubs became … good!

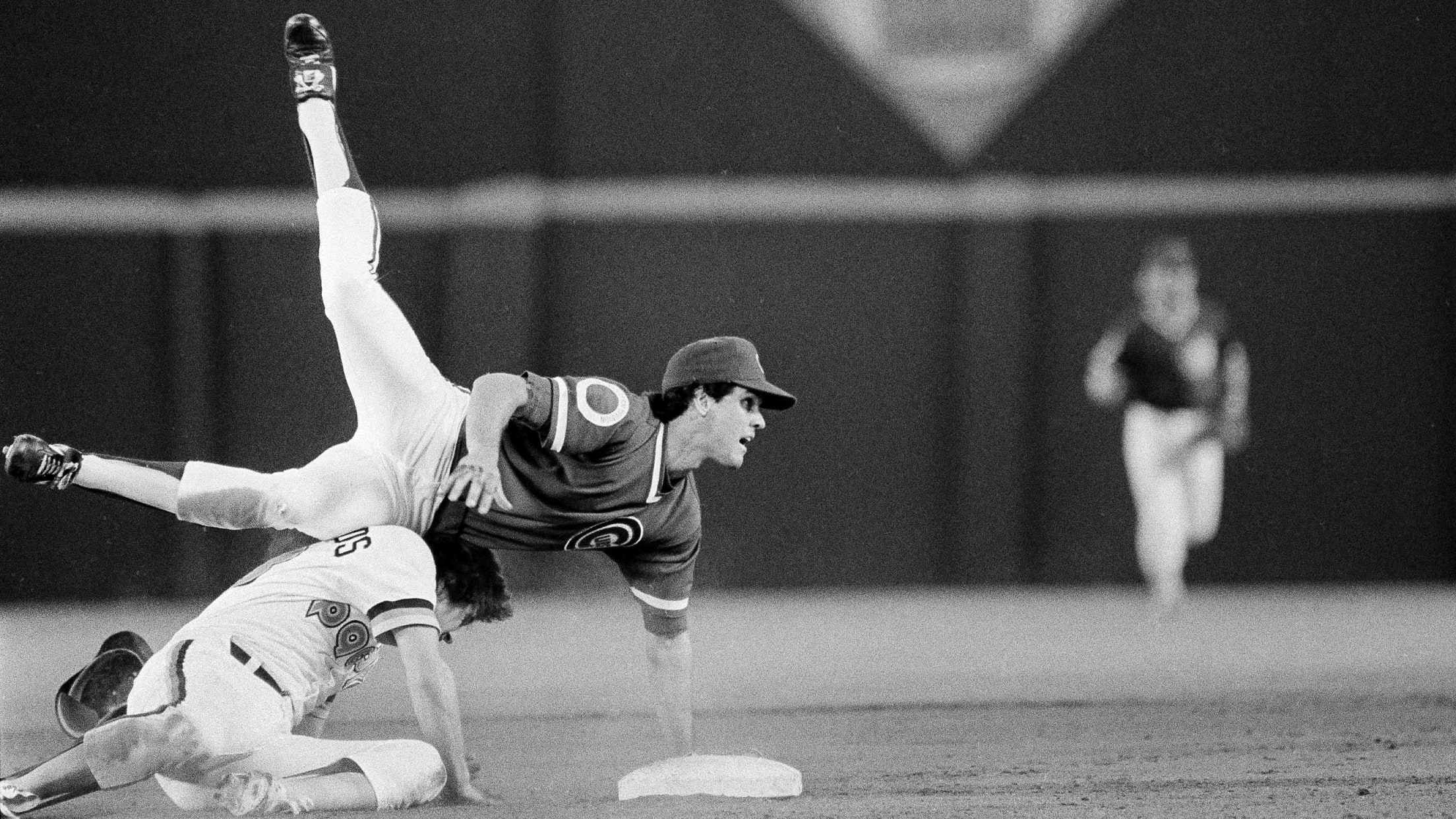

Green might not have known much about proper discourse in public meetings, but he knew how to build a baseball team. And with the emergence of Ryne Sandberg as an MVP and Green successfully rebuilding the pitching staff with trades for Dennis Eckersley, Scott Sanderson and Sutcliffe, the 1984 team, which won 96 games and the NL East, became a viable threat to reach the World Series.

That would have made for a great story in baseball, if not for one big problem: Just the previous year, the league had signed a $1.2 billion television pact with ABC and NBC that called for primetime World Series games. Day baseball at Wrigley threatened to tarnish the golden goose.

This was back in the days when home-field advantage in the World Series alternated each year between the AL and NL. In 1984, it was the NL’s turn, which meant if the Cubs could get past the San Diego Padres in the NL Championship Series, they were due a distinct competitive advantage in the Fall Classic.

Because of the lights issue, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn came up with a compromise: If the Cubs reached the World Series, they could have their home games. But those games would be Games 3, 4 and, if necessary, 5 -- wrapped around a weekend. This would allow MLB to preserve the primetime weeknight TV slots for the other games.

“It shows you the power that TV was starting to have inside the game,” Colletti says. “I’m old enough to remember all the World Series games in the daytime. Suddenly, now you’re going to change a venue because of the influence and the partnership of television.”

This all turned out to be moot. The Cubs lost the NLCS to the Padres in five games. (The home-field factor turned out to be moot, too. The Padres had the advantage in the World Series but lost in five games to the Tigers.)

Yet by actually fielding a competitive club, the Cubs had pushed the lights issue to the forefront. And that meant a more serious discussion was looming in 1985.

* * * * *

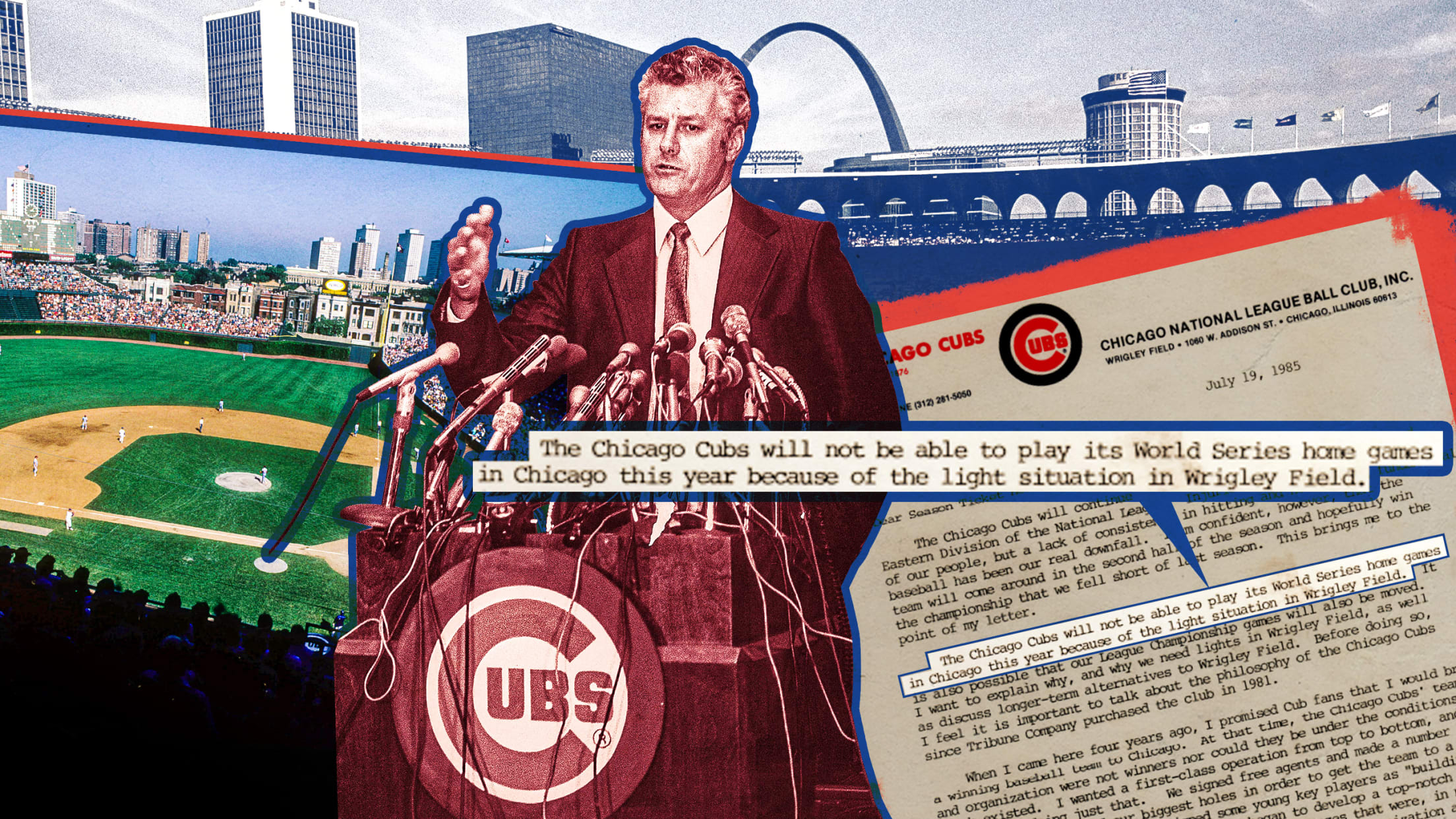

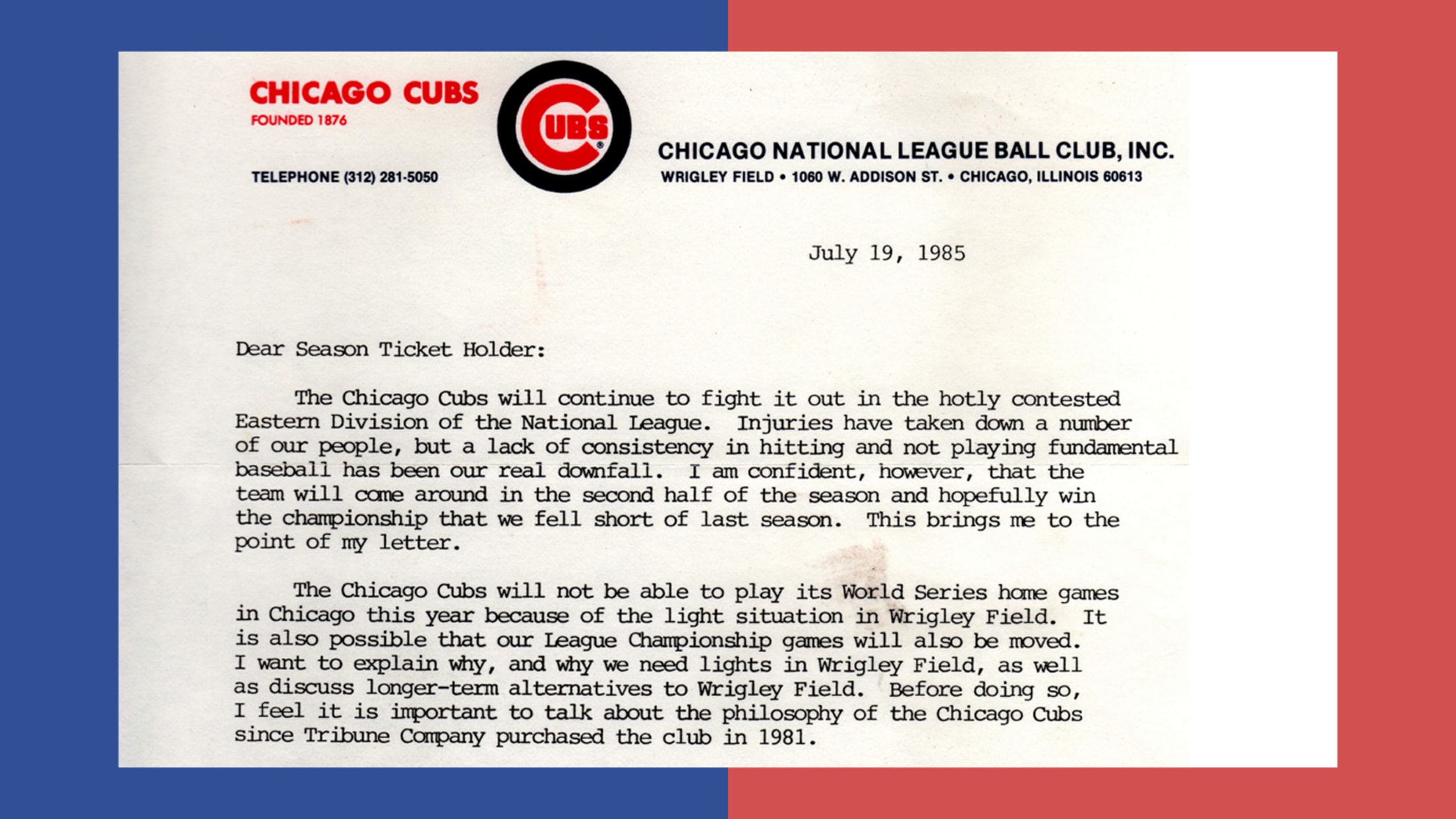

The letter begins with brief baseball banter, bemoaning the injuries and poor execution that contributed to a summer swoon in the standings.

Then Green gets down to business.

“The Chicago Cubs will not be able to play its [sic] World Series home games in Chicago this year because of the light situation in Wrigley Field,” he writes. “It is also possible that our League Championship games will also be moved.”

This letter to Cubs season-ticket holders -- dated July 19, 1985 -- goes on to explain the financial limitations of Wrigley, the national television contract that allowed the networks to insist on night World Series games and the warning the Cubs had received from the new Commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, that MLB was prepared to take the drastic action in '85 (moving the Cubs’ home games away from their home park) that it had avoided in '84.

How much of this letter was an exaggerated attempt to curry favor for lights from the fan base? Well, at the time it was written, the Cubs were in the midst of a 10-23 funk that had dropped them from first to fourth in the NL East. So it didn’t appear realistic that the Cubbies would be playing October games at Wrigley, either way.

Then again, 7 1/2-game midseason deficits had been erased before. And with the Cubs in the midst of a court battle over the ban on night games that had reached the Illinois Supreme Court, and with MLB and the networks pushing hard for the lights situation to get settled, a greater sense of urgency was in the air.

The Cubs had conversations with MLB about at least two possible postseason “home” sites -- Milwaukee County Stadium and St. Louis’ Busch Stadium. The former had appeal in that it was close enough to be a relatively easy commute for Cubs fans, but the Brewers were still an AL club at the time in the days before Interleague Play, so most of the Cubs players were unfamiliar with the ballpark’s clubhouses, dimensions and quirks. For that reason, St. Louis had appeal in that Cubs players were well acquainted with the home of their NL East rivals.

“The one place I know we were never going to go would be over to the White Sox ballpark [Comiskey Park],” Ibach says. “Because the Cubs fans would have killed us!”

Of course, Cubs fans wouldn’t have been happy with Milwaukee or St. Louis, either. It’s one thing to have the Toronto Blue Jays playing “home” games in Buffalo in 2020 because the Canadian government did not deem it safe for them to play in Toronto during the COVID-19 pandemic. Or for MLB to put the Division Series, League Championship Series and World Series at neutral sites to reduce the risk of an outbreak.

The one place I know we were never going to go would be over to [Comiskey Park].

Bob Ibach, former Cubs director of public relations

It’s quite another to envision Sandberg playing World Series home games on Ozzie Smith’s field merely because of a TV schedule.

So how serious did these conversations get? Former Cubs president Donald Grenesko told ESPN in 2017 that the club had signed a contract to play postseason games at Busch. This claim could not be corroborated, and Grenesko did not respond to messages seeking a follow-up interview.

“I think it was more threat-oriented than anything,” Colletti says. “Because the team had such a difficult time with the neighbors and aldermen.”

That difficulty continued for two more years. The Cubs lost their Illinois Supreme Court case in October 1985, which meant that they were still barred from staging night games at Wrigley. And when the threat of an all-road World Series ultimately didn’t move the needle, the Cubs went to the next level:

They threatened to move to the suburbs.

Night games at Wrigley posed challenges for local residents, but those challenges were nothing compared to the threat of not having any games -- and the accompanying economic boost -- at all. A WGN documentary, “The Ivy Walls May Fall,” aired in October 1985 (when the Cubs might otherwise have been donning their home whites at Busch) and helped sway public support away from the C.U.B.S. and to the Cubs.

When Green left the Cubs in 1987, the icy relationship between the residents and the team began to thaw. Ultimately, the Chicago City Council voted in February 1988 to allow eight night games at Wrigley that season and 18 in future seasons. (The unique 2020 season became the first in which the Cubs got the OK to have weekend night games at Wrigley.)

By the time the Cubs returned to the NLCS in 1989, they were no longer in danger of having to play World Series home games away from home. Unfortunately, it was still many years before they played in any World Series games at all.

The wait, though, proved worth it in 2016. Celebrating such a historic final out in Cleveland, not Chicago, wasn’t optimal. But it was a heck of a lot better than the thought of celebrating it in St. Louis.