The player who nearly integrated baseball in 1905

It sounded like a done deal. Per a “person on the inside,” a newspaper report revealed that a National League team would be adding a new player “very soon.”

This was no ordinary player. He was a player of, as the paper put it, “remarkable ability,” sure to “prove a great attraction and a big drawing card.” He was a skilled middle infielder who engendered respect for the way he comported himself on and off the field.

He was also Black. And his arrival would make him the first player to cross the color barrier in the modern Major Leagues.

What sounds like the setup to Jackie Robinson joining the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 actually precedes that essential event by more than 40 years. It is, instead, the story of a would-be pioneer who possessed many of the same traits as Robinson at a time when society, at large, was unwilling to recognize them.

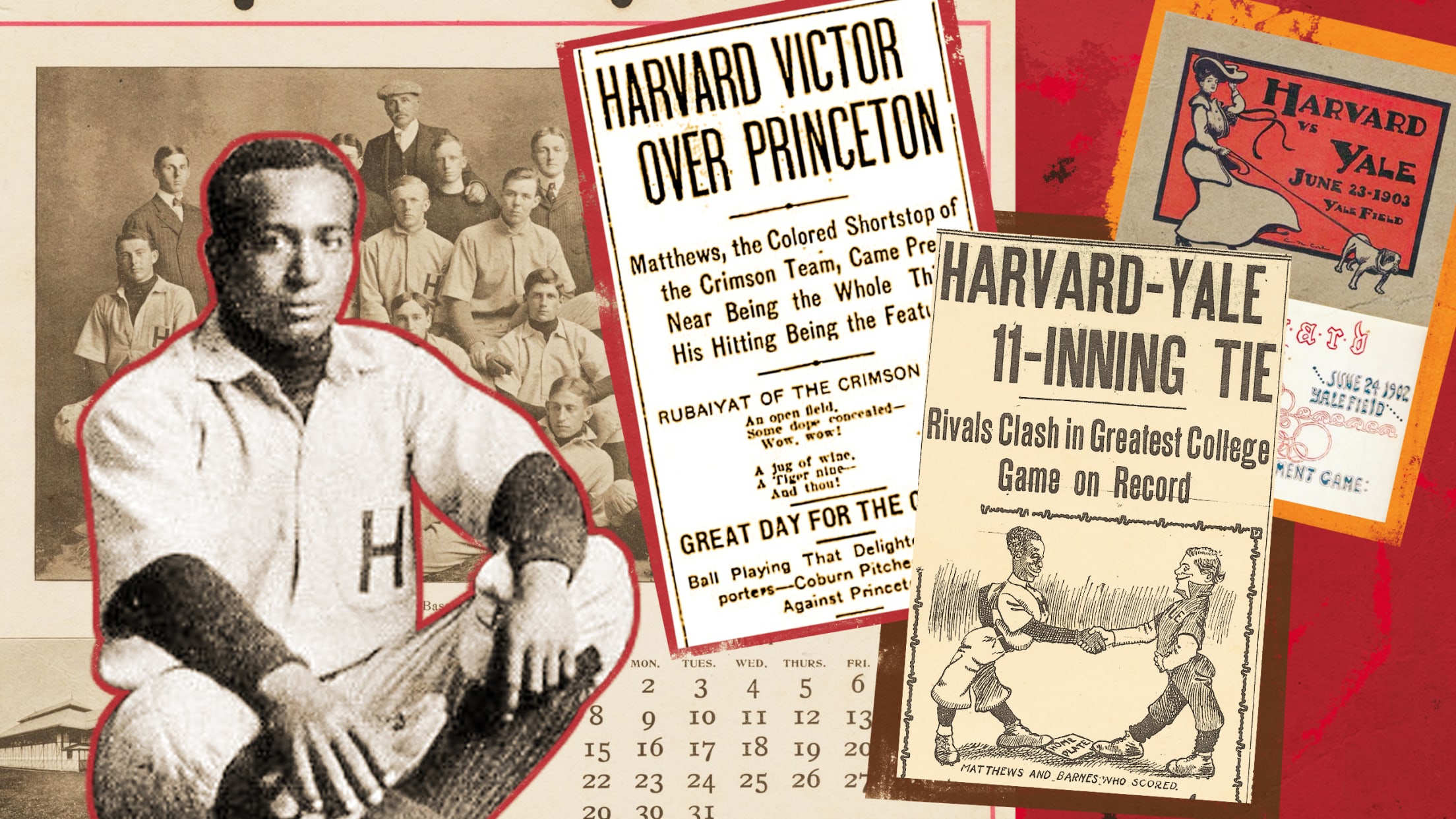

Most people alive today have never heard the name William Clarence Matthews. They don’t know what a star he was in his time and place. They don’t know that his baseball story intersected with those of Hall of Famers Denton True “Cy” Young and “Wee Willie” Keeler. Or that his life story converged with those of such important historical figures as Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey and President Calvin Coolidge.

Matthews’ tale is largely lost.

But a stray report by a Boston newspaper in the summer of 1905 offers a fascinating alternate history for Matthews and for his sport. Through this obscure relic, we learn more about the complicated nature of race and culture in early 20th century America. We also see how societal progress could have been ushered in sooner. How the National Pastime’s unwritten-but-impassable color line could have been broken earlier. And how Matthews himself could have been the icon that Robinson became.

What it would have taken was some rare fortitude from one of the worst teams in baseball.

The 1905 Boston Nationals -- the team sometimes known in the press as the “Beaneaters” and the franchise that would eventually become the “Braves” -- were languishing just a half-game out of last place in the NL entering play on July 15. While their roster was awash in weakness, their performance in the middle infield was especially appalling. By that point in the season, starting shortstop Ed Abbaticchio had already made 50 errors. Second baseman Fred Raymer wasn’t much better in the field, and his midseason .251 average at the plate made the second sack a sad sack.

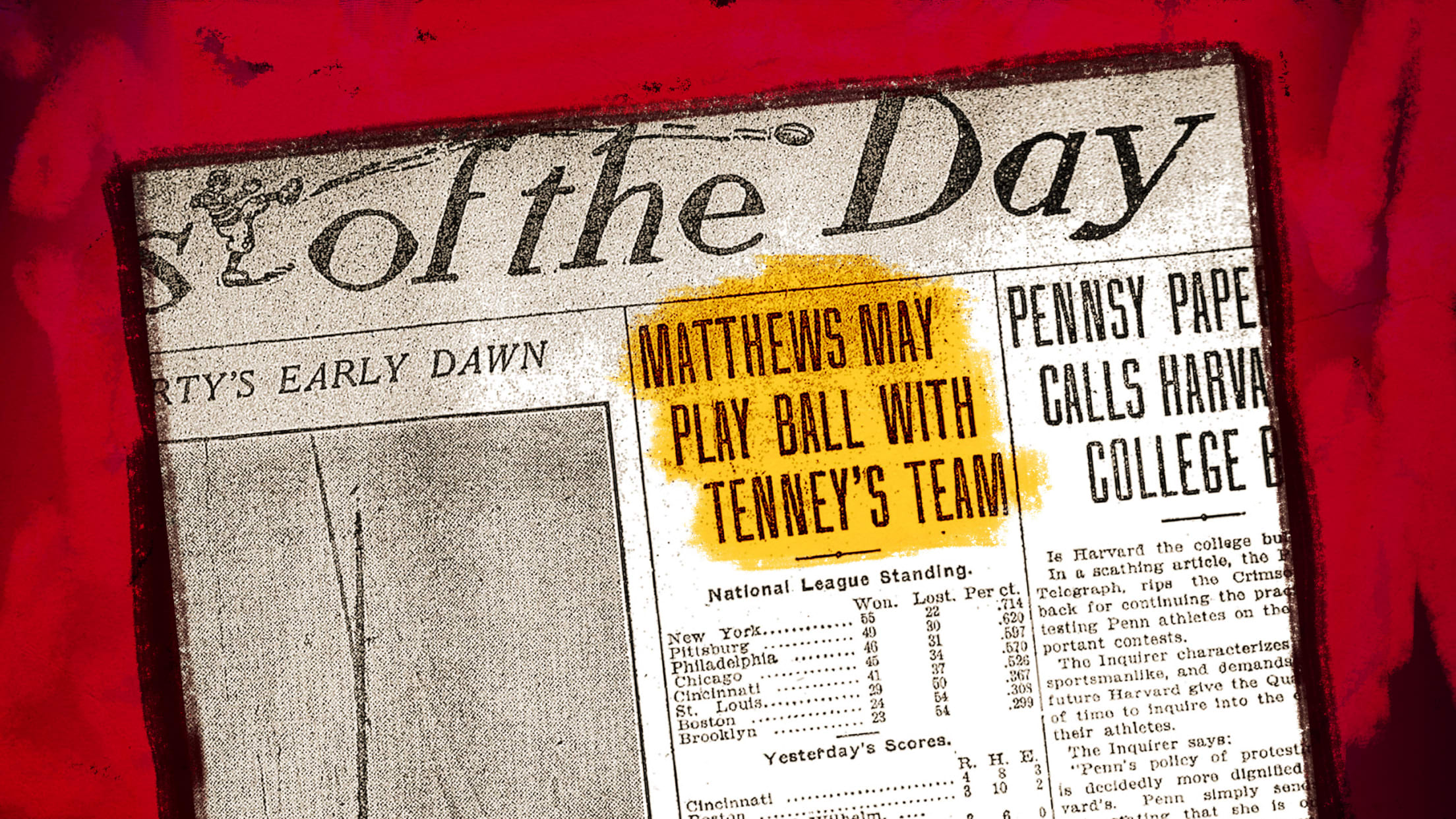

So one could understand why player-manager Fred Tenney, in his first season as skipper, might have been open to a change. And the change proposed in a headline on the sports page of that evening’s Boston Traveler was radical.

“Matthews May Play Ball with Tenney’s Team,” it read.

That Matthews was on even so much as a last-name basis in a newspaper headline speaks to his status in the New England sports scene at the time. He had recently completed a successful career at Harvard, where his contributions to both the baseball and football teams were well-documented by the local press. The Traveler was one of nine daily newspapers in Boston at the time, and the four with the largest circulation -- the Globe, the Post, the Herald and the Evening Record -- covered the Crimson regularly.

Matthews, therefore, had skills and, regardless of his race, a certain degree of status in the local sports scene.

“We have to look at this in the context of history,” says Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester. “America during that period was under the separate but equal doctrine, upheld by the 1896 Supreme Court decision [in Plessy v. Ferguson, which allowed state-sponsored segregation]. The most visible Black athletes at that time were jockeys. The Black athlete was not acceptable in mainstream society and especially not in the most popular sport in America. That tells me that William Clarence Matthews must have been one hell of a shortstop.”

It is impossible, well more than a century later, to climb into Tenney’s mind and determine whether he would have been open to a Black player joining his baseball team. But we do know his father fought for the Union Army in the Civil War. We also know that, like Matthews, Tenney was an Ivy Leaguer, a product of Brown.

Between his connection to his alma mater, his offseason coaching at Tufts and what was written in the press, Tenney would have been keenly aware of a local player capable of augmenting his infield.

“One can understand,” says Karl Lindholm, an emeritus dean of advising and assistant professor of American studies at Middlebury College, “if Tenney might have cast a longing eye across the Charles River to Matthews.”

"The Black athlete was not acceptable in mainstream society and especially not in the most popular sport in America. That tells me that William Clarence Matthews must have been one hell of a shortstop.”

Lindholm has become the modern-day authority on Matthews, and his research was essential in preparing and presenting this story. Lindholm first became intrigued by Matthews when reading brief mention of an unnamed National League manager’s interest in the Harvard shortstop in Robert Peterson’s seminal “Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams.” Like many researchers and historians, Lindholm surmised that the manager in question was legendary New York Giants skipper John McGraw, a known combatant of the color barrier.

Only when he took a sabbatical from Middlebury in the mid-1990s and spent countless hours scouring the Boston Public Library’s microfilm collection and, in his words, “getting a sore arm” did Lindholm learn otherwise. He found the original report in the July 15, 1905 edition of the Traveler -- the link between Matthews and “Tenney’s Team” that creates the ultimately unanswerable question as to whether this rumor was rooted in reality.

“When you say, ‘William Clarence Matthews was rumored to be breaking the color barrier in 1905,’ that’s true, because it was a rumor,” Lindholm says. “The question is whether or not it’s plausible.”

Any plausibility to the report derives from Matthews’ excellence as an athlete and his character as a person.

Born in Selma, Ala., in 1877 -- the tail end of the Reconstruction Era -- and raised in Montgomery, Matthews led a too-brief life of great accomplishment despite the bounds of bigotry. From 1893-97, he attended Tuskegee Institute, where he trained to become a tailor like his late father, William, and wound up organizing a football team, captaining the baseball team and graduating as the salutatorian of his class.

“Captain Matthews behind the bat gave an exhibition of sand that would have inspired any team to win.”

Booker T. Washington, director of the Tuskegee Institute, was the one who helped Matthews get an opportunity to continue his college preparation at the prestigious Phillips Andover Academy, where Matthews was the only Black student in a class of nearly 100 young men. Through his baseball, football and track feats, Matthews earned the acceptance of his fellow students, who particularly admired his willingness to move from shortstop to catcher to fill a need late in the season while playing through a particularly gruesome thumb injury. When Andover beat arch-rival Exeter in a best-of-three series, Matthews was hailed as the hero.

“Captain Matthews behind the bat,” wrote the school newspaper, “gave an exhibition of sand [translation: grittiness] that would have inspired any team to win.”

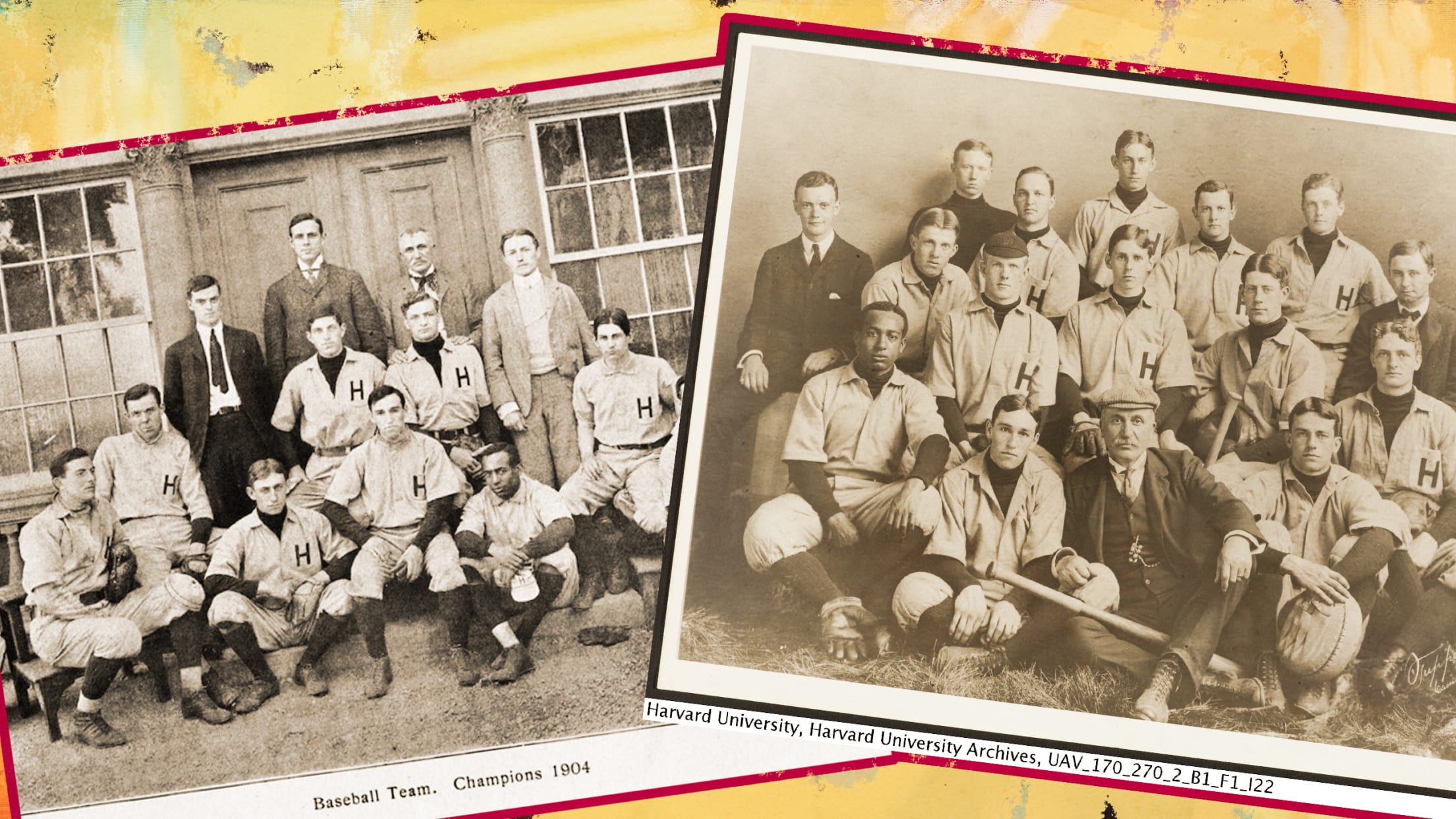

With a recommendation from Phillips Andover principal Cecil Bancroft, Matthews was admitted to Harvard, where his academic and athletic exploits continued. For Matthews to not only start for but star for a Harvard team that would go 75-18 in his four years there is testament to his talent.

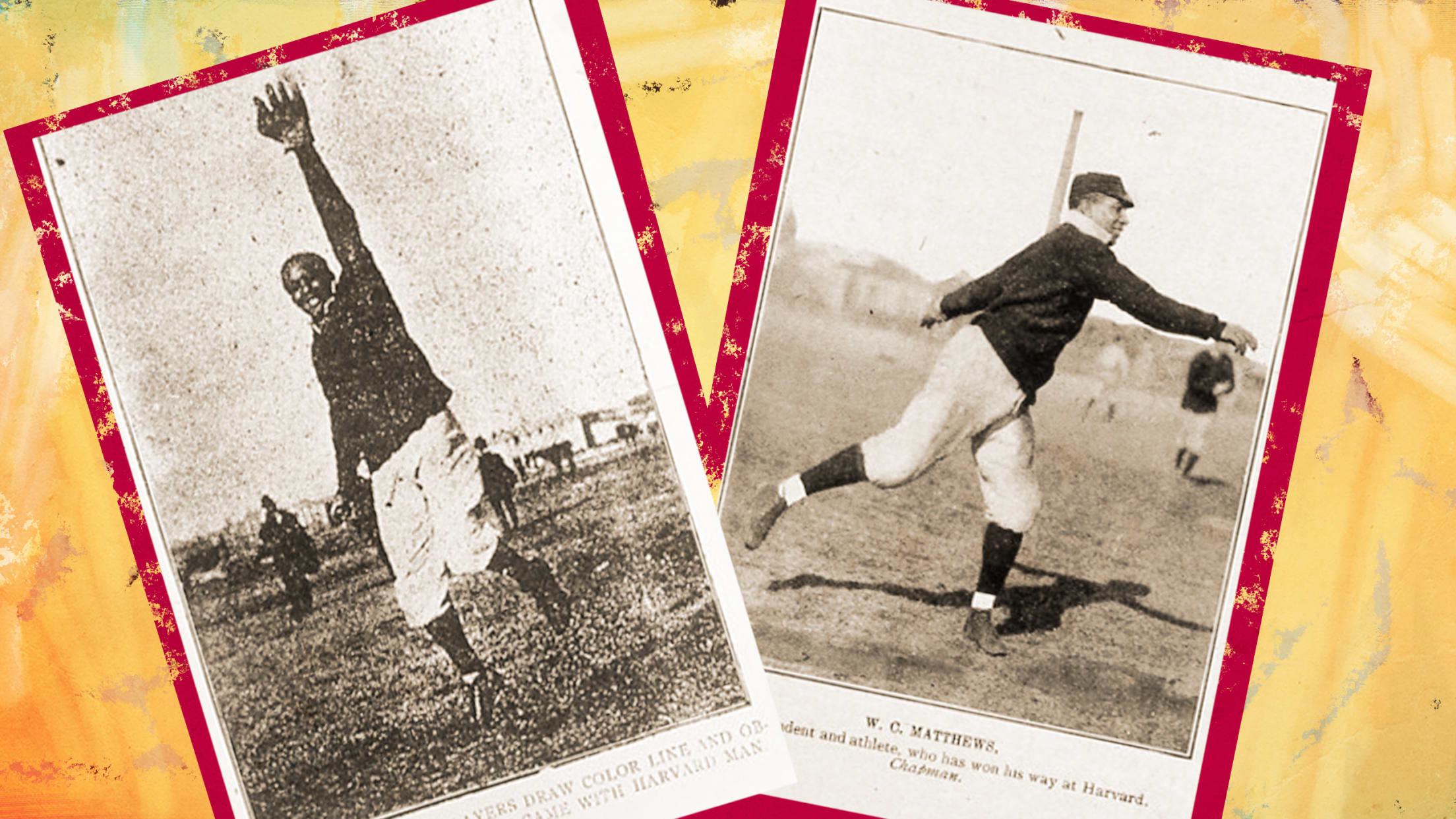

In those days prior to the establishment of the Minor Leagues, the collegiate ranks were a vital big-league breeding ground. And in Matthews’ freshman season at Harvard, in 1902, the Majors had an acute influence. The Crimson pitchers that spring were coached by no less an authority than Cy Young himself, in advance of his second season with the Boston Americans. The position players, meanwhile, were presumably instructed to “hit it where they ain’t” by their batting coach, Willie Keeler.

Harvard produced three big league players of its own during Matthews’ time there. Catcher Jack Robinson (obviously, not to be confused with Jackie Robinson) finished up at Harvard in Matthews’ freshman season of 1902, then played nine games with the Giants later that year. The Crimson’s 1903 captain, Walter Clarkson, pitched five seasons for the New York Highlanders and Cleveland Naps from 1904-08. And Matthews’ double-play partner, second baseman Eddie Grant, played in 10 seasons for four teams from 1905-15.

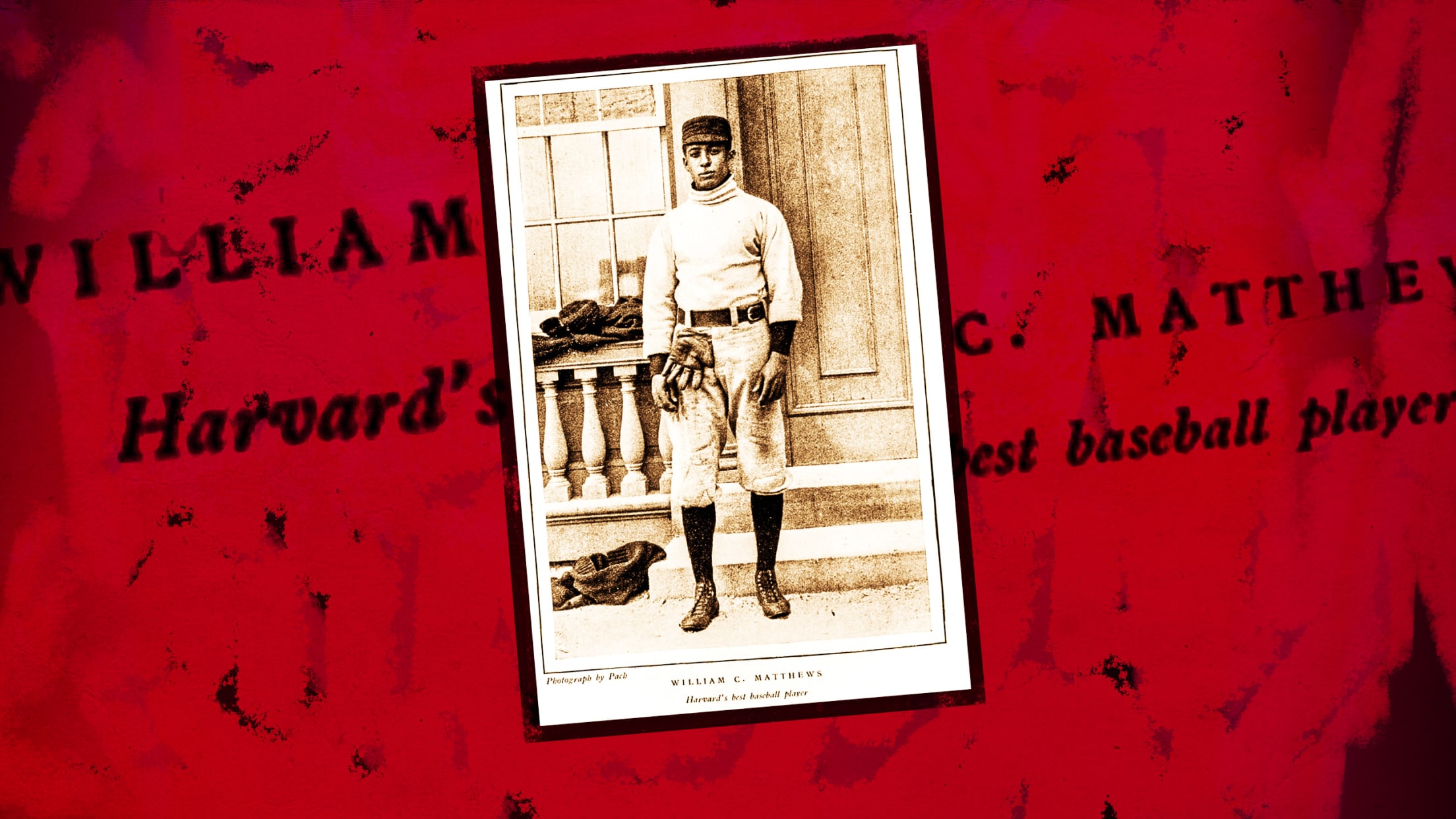

Matthews, however, was never granted access to the Major League stage, even though he was Harvard’s best player. After missing half of his freshman year with a knee injury, he led the team in hitting his sophomore, junior and senior seasons while also impressing with his glove at short and his legs on the basepaths. Measured at 5-foot-8, 145 pounds, Matthews was no giant in literal stature. But he commanded attention with his play, especially given his propensity to come through in the clutch against rival Yale. The Boston Post went so far as to label him “the best infielder Harvard ever had,” the school’s “greatest big league prospect,” and, in an especially breathless claim, “no doubt the greatest colored athlete of all time.”

Beyond his gifts as a ballplayer, Matthews was celebrated for his honorable approach to a sport that, in that era, often devolved into a lawless affair. In 1905, the Boston Globe waxed poetic about Matthews’ ethics:

“For seven years Matthews could have earned much money by playing for semi-professional teams but this he has refused to do … Here is a man who to maintain his amateur standing has repeatedly refused offers of $40 a week and board to play semi-pro baseball in the summer. He had the example of many contemporaneous college ballplayers who were accepting ‘indirect’ compensation in an underhanded way but he has kept his record clean, and his, it is sad to say, is an exceptional case.”

Of course, because this was America in 1905, attitudes toward Matthews weren’t always so approving.

In his freshman year, he stayed back in Cambridge when Harvard ventured into the South to play at Virginia and Navy. In his sophomore year, Georgetown threatened to boycott a game against Harvard if the Crimson didn’t pull Matthews from the lineup. Though the Georgetown team ultimately relented, its captain and catcher, Sam Apperious, who also hailed from Alabama, refused to play against a Black opponent.

The crowd wasn’t welcoming, either.

“Matthews displayed the abilities of a first-class ballplayer and conducted himself in a gentlemanly manner,” the Washington Star reported. “Notwithstanding, there were hisses every time he stepped up to bat and derisive cheers when he failed to connect with the ball. The little shortstop took no notice of these demonstrations occasioned by the prejudice of a number of spectators.”

The support Matthews received from his white teammates at that point in the nation’s history is noteworthy. During his senior year, the Harvard team, unwilling to bow to Southern sentiment, canceled trips to Annapolis and Trinity (now known as Duke) on the eve of its scheduled departure.

These experiences helped prepare Matthews for what awaited him after he completed his Harvard career and ventured off to the only place where a Black man could find a place to stand in a white man’s professional league in 1905 -- the remote baseball bulwark of Burlington, Vt.

On July 4, 1905, Athletic Park buzzed in anticipation of the home debut of the local nine’s new shortstop. For weeks, his identity had been kept secret as he fulfilled his college obligation. But on June 28, the Boston Globe had revealed that William Clarence Matthews, star of the Harvard squad, was indeed Burlington-bound to play for the city’s unit in the Northern League, an independent league unaffiliated with the Major Leagues.

In his debut on the road, Matthews was, as the Burlington Free Press put it, “liberally applauded” by the Burlington fans who had traveled by train. And those same fans had more to cheer when Matthews cranked out three hits in an Independence Day doubleheader against Rutland.

With Matthews’ arrival, the Northern League was integrated, becoming quite likely the only predominantly white professional league at that particular point in time that could make the claim.

But Matthews’ arrival was not warmly greeted by all. When he first joined Burlington, a pitcher referred to only as “Smith” was reported by the Montpelier Argus to have left the team in disgust. Matthews also faced the wrath of some opponents. There were reports of him getting intentionally spiked, much the same as Robinson would decades later.

“I think it is an outrage that colored men are discriminated against in the big leagues. What a shame it is that black men are barred forever from participating in the national game. I should think that Americans should rise up in revolt against such a condition."

Once again, Matthews’ path crossed with that of Apperious, who was now on the Montpelier-Barre squad. And once again, Apperious made it known that he would not play on the same field as a Black player.

To their credit, most of the newspapers in Vermont -- a state with Abolitionist roots -- condemned Apperious.

“Mr. Apperious had better retire to those places where peonage is still in practice,” wrote the Newport Express and Standard, “where he can still vent his spite on the Negro as his little, narrow-minded, measly soul desires.”

The national perspective -- and the story did, indeed, go national -- was not as favorable to Matthews. The Sporting Life reported that the arrival of “the Negro shortstop from Harvard into the Vermont League [sic] threatens to disrupt that organization.” The Atlanta Journal, an influential baseball publication, sneered, “The debut of the human chocolate drop is about to break up this league.”

It’s possible the attention that so often singled him out got the best of Matthews over the course of what would be his only season in professional ball. After joining the team in early July, he hit .314 in his first 13 games, but his performance fizzled by the end of the summer. He was spiked so often that he was moved from shortstop to the outfield to lessen his odds of injury.

But Matthews’ bat was still ablaze at the time of the Boston Traveler rumor. And within that July 15, 1905, piece, we hear from the man himself, with quotes relayed from “a Vermont newspaper man.”

Matthews’ words are powerful:

“I think it is an outrage that colored men are discriminated against in the big leagues. What a shame it is that black men are barred forever from participating in the national game. I should think that Americans should rise up in revolt against such a condition.

“Many Negroes are brilliant players and should not be shut out because their skin is black. As a Harvard man, I shall devote my life to bettering the condition of the black man, and especially to secure his admittance into organized base ball.

“If the magnates forget their prejudices and let me into the big leagues, I will show them that a colored boy can play better than lots of white men, and he will be orderly on the field.”

Alas, while the Northern League was willing to open the door to Matthews, affiliated baseball -- much like American society, in general -- proved averse to such a breakthrough.

Fred Tenney’s Boston Nationals would complete the 1905 season with a 51-103 record, part of a stretch of 14 consecutive seasons at the start of the 20th century in which the franchise finished no better than 17 games out of first place in the NL. Between the record and the muddled middle infield, we can say with relative certainty that Matthews would have improved the club. The July 15 report in the Traveler assumed as much, claiming that “William C. is just the laddybuck [Tenney] needs.”

But the Traveler made another assumption that was far more suspect.

“Of course,” the article reads, “Captain Tenney will have to consult with the magnates but there is little fear of objection on their part.”

This confidence was clearly misguided. The article generated significant conversation within the sport and commentary in several newspapers around the country, and the quoted remarks of Cubs president Jim Hart in the Chicago Daily News best demonstrate the intractability a Matthews move would have been up against.

“Personally, I have no objections to a Negro playing baseball,” said Hart, “but I do not think it is right to inflict him on others who have objections or forcing white players to sleep in the same car with him and associate as intimately as they would have to under such conditions. That is the real objection to a Negro in baseball.”

Hart added that National League president Harry Pulliam’s “good Southern blood would never stand for it.”

This brings us back to the question of the rumor’s plausibility. The Traveler, which had a decently sized circulation of around 80,000, was the only one of the nine Boston newspapers to report the rumor. The others either dismissed the rumor in print or ignored it completely. Given what we know about Tenney, it is plausible that he really did give serious consideration to adding Matthews. And it is equally plausible that the Traveler -- a paper with a reputation for sensationalizing some stories -- greatly inflated an impractical idea.

“The Traveler was in a heated newspaper war,” says Lindholm, “and this was really good copy.”

Maybe, given the aforementioned attitudes of the time, Tenney’s role in all of this is immaterial. He might have been unable to buck the segregated system, even if he did indeed try.

All we know for sure is that from the day of the Traveler’s report of Matthews’ supposedly imminent arrival, it would be almost 42 full years before Jackie Robinson would debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. And the cruel irony in all of this is that Boston -- the city where Matthews’ baseball feats were so widely reported and celebrated and where he could have augmented Tenney’s hapless bunch -- wound up as the last Major League city to integrate. The Red Sox finally fielded a Black player in 1959, a dozen years after Robinson’s Dodgers debut.

Affiliated baseball wasn’t ready for William Clarence Matthews. But the beauty of his story is that he didn’t need the game’s platform to make his mark on American society. If he had never played an inning of baseball in his life, his story would be worth telling all these years later.

At the end of the Northern League season in 1905, Matthews was a 28-year-old Harvard graduate, which is to say he had other options in life. He enrolled in Boston University Law School, and he passed the bar in 1908.

“This man was athletically and intellectually talented,” Lester says. “He had the total package. This man had to have an incredible mental capacity to put up with so much racism -- legal racism.”

Matthews’ mentor was William H. Lewis, a pioneer in both sports (he was the first Black college football player to be named an All-American) and in law (he was the first Black person appointed as an assistant U.S. attorney and a U.S. assistant attorney general). The two established a legal practice together in Boston, and Matthews stayed involved in sports by coaching high school teams on the side.

Unlike in professional baseball, where his path to prominence was impeded, Matthews quickly gained larger responsibilities in the legal world. In 1912, he was appointed by President William Howard Taft as special assistant to the U.S. district attorney in Boston, succeeding Lewis.

Matthews’ most curious appointment was as legal counsel to Marcus Garvey – the Jamaican-born leader of the Pan-Africanism movement and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, which came under the scrutiny of the U.S. Department of Justice. Aligning with Garvey would appear to be at odds with Matthews’ public persona and political interests. In fact, while in exile in London in 1928, Garvey publicly accused Matthews of serving as an FBI informant while working for him.

“I did enough research,” Lindholm says, “to not find anything to support that.”

Whatever the case, Matthews became leader of the Republican Party’s so-called colored section that generated support in Black communities for Calvin Coolidge in the 1924 presidential election. Coolidge cruised to victory with the help of more than one million Black voters, and Matthews, like Lewis before him, was appointed as an assistant U.S. attorney general.

That was the role Matthews was serving when, on April 9, 1928, he died suddenly from a perforated gastric ulcer, at the age of 51. In the Black newspapers, in particular, his death was front-page news. The New York Age, a prominent Black weekly, gives a window into how endearingly Matthews was viewed with its succinct summary above his photo: “‘Matty’ is Dead.” In various accounts, Matthews was described as “one of the most prominent Negro members of the bar” and a “leader of the colored race.”

And of course, Matthews’ athletic career was mentioned prominently in his obituaries.

“Whenever he played baseball or football against Yale or Princeton, something dramatic was sure to happen, a spectacular home run, a lightning double play, a hair-raising tackle,” read the New York Amsterdam News. “The sporting pages of the newspapers were full of his name.”

And so that name was known to many in the early 1900s. But time passed. Aside from having the Ivy League baseball championship trophy named in his honor in 2006 and getting inducted into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014, Matthews became a somewhat forgotten forebearer, his story scoured and shared by only the most curious students of history.

Lindholm, who hopes to one day tell Matthews’ tale in greater detail in a full biography, has taken to calling him “The Black Matty,” juxtaposing Matthews with 1905 World Series hero Christy Mathewson of the New York Giants. Both the white Matty and the Black Matty were skilled and admired at that particular point in baseball history. But only one was permitted to play in the Major Leagues.

A more natural comparison, of course, is to Jackie Robinson, whose iconic entry we celebrate each spring on April 15.

“Matthews was emblematic of the college-educated African-American -- the very sort that Major League Baseball would later recruit,” says official MLB historian John Thorn. “If Branch Rickey had been looking for someone with the credentials of a Jackie Robinson, someone who would not rise to the bait of racist players and fans, Matthews would have been that guy.”

Like Robinson, who passed away at age 53, Matthews managed to pack a lot of life into his years and to live a life of great achievement in a segregated country. And like Robinson, he used his baseball talent to make a broader point about injustice. Though denied the debut that talent deserved, Matthews ought to be appreciated now as one of the many broad shoulders upon which Robinson stood. For when Jackie arrived in 1947, he wasn’t just opening the door for the many great Black athletes who followed; he was upholding the assertion Matthews had long ago made.

“A Negro is just as good as a white man,” Matthews said in what could have and should have been the fateful summer of 1905, “and has just as much right to play ball.”

[A version of this story originally ran in April 2021].