This team moved home plate ... to hit HRs and win more games

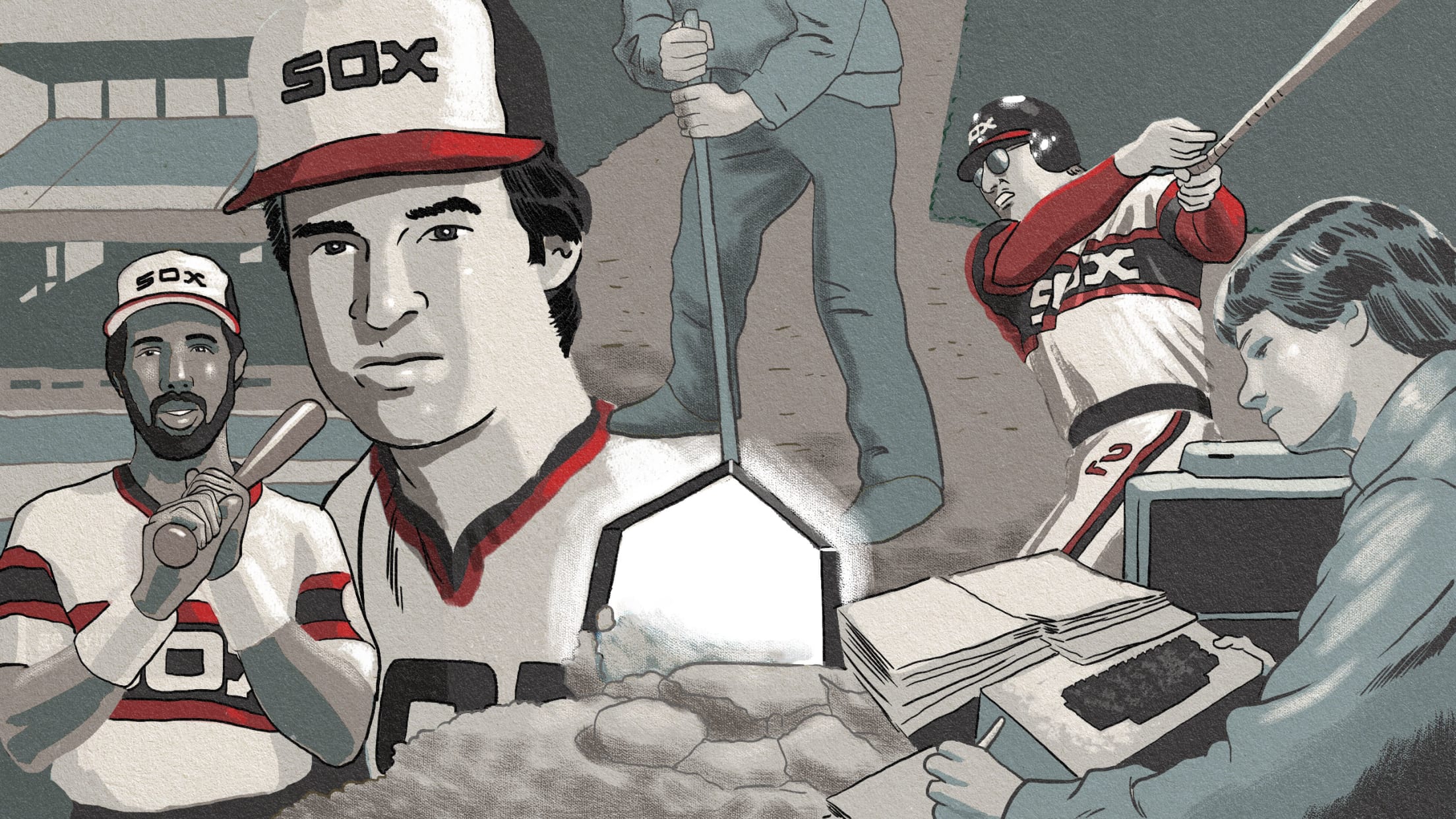

The future Hall of Famer and the number-cruncher were standing in the outfield grass one day during batting practice at old Comiskey Park, shagging fly balls and shooting the breeze. It was nearing the end of the 1982 season, and the White Sox were on their way to a solid-but-unspectacular third-place finish, the 23rd consecutive season in which they would miss the playoffs.

“We’re losing more balls to the warning track than our opponents,” Sox right fielder Harold Baines casually mentioned to Dan Evans, the 23-year-old, fresh-out-of-college kid entrusted with running the South Siders’ nascent computer system.

So Evans went around the field, discussing Baines’ observation with some of the hitters and pitchers. And then, late that night, after the game, he conferred with the baseball statistics database installed on his Apple IIe.

Baines was right. The cavernous confines of Comiskey, Evans confirmed, were working against the home club.

“To that point in the season, our opponents had benefited something like 30 times more than us, because our fly balls were going to the warning track,” Evans says now. “If the dimensions were different, we could have had about 30 more home runs.”

The story of the White Sox in 2021 is that an elderly skipper named Tony La Russa made an unexpected, at-times-awkward and ultimately successful return to Chicago, guiding the club to its first American League Central title in more than a decade.

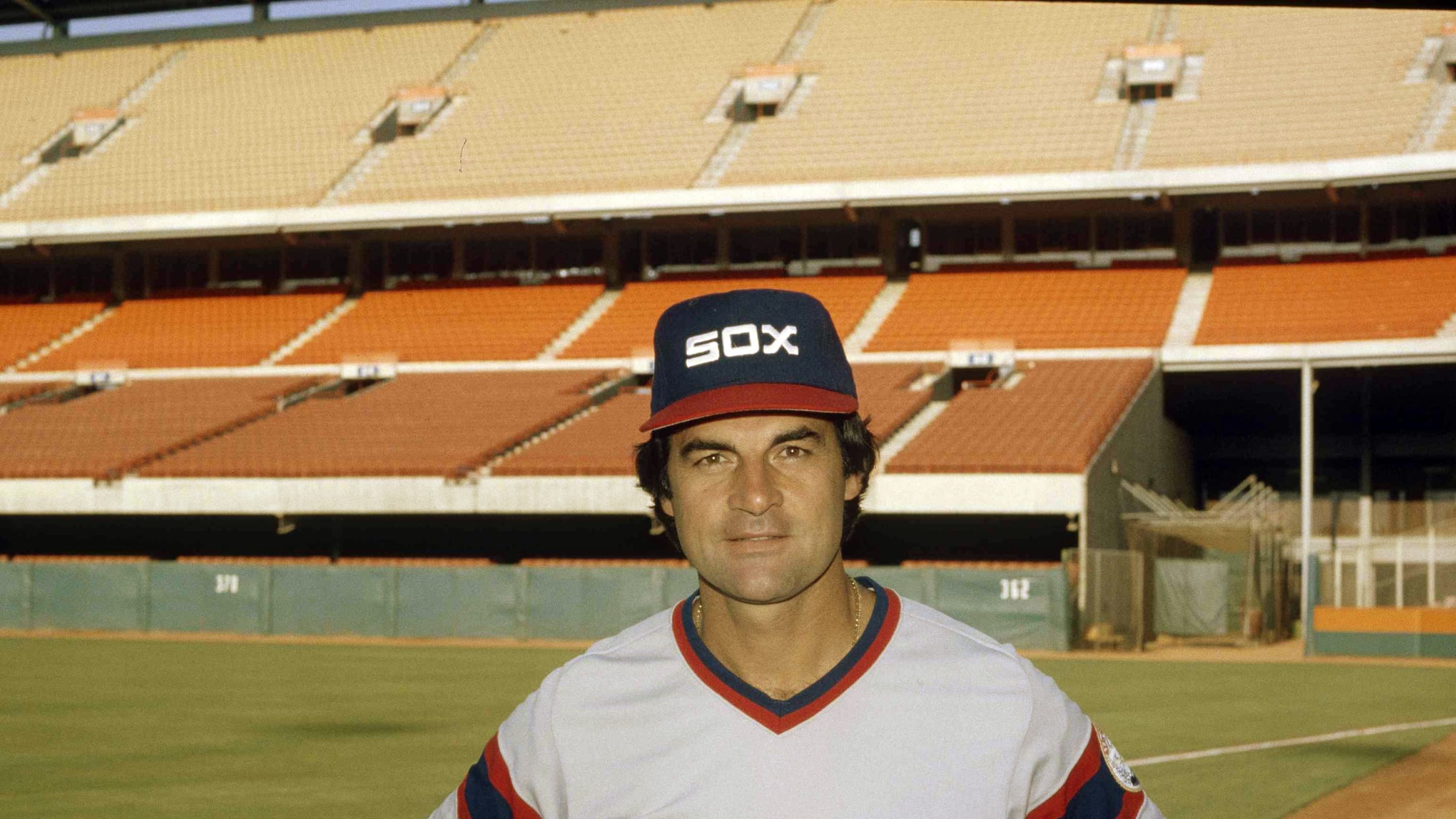

But back in the early 1980s, when La Russa was one of the youngest managers in the Majors, his openness to unorthodox ideas and his team’s trust in what Evans and the computers were documenting helped the Sox overcome an even deeper drought.

Sure, it was unusual when the present-day Sox hired a 76-year-old to manage an up-and-coming club. Yet that’s nothing when compared to uprooting and repositioning a 72-year-old diamond in order to hit more dingers.

This is the story of how the 1983 White Sox changed their fortunes by changing their field.

* * * * * * * *

The internship was supposed to be a lark, a diversion. Evans studied pre-law and communications at DePaul and was under the misguided impression that he was going to be a criminal prosecutor. But the opportunity to intern for his hometown White Sox during the spring semester of his junior year of college in 1981 was too good -- or at least, too fun -- an opportunity to pass up.

Once Evans stepped into Comiskey Park in a work capacity, he began to view his job prospects quite differently.

“I was their first intern in who knows how long,” Evans says now. “Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn had just bought the team in January of ’81, and they only had about 20 full-time staff members [in the front office]. So my job was a hybrid between the baseball department and the media relations department.”

That job served as a special springboard for Evans. He would wind up spending nearly 20 years with the White Sox, playing an influential role in drafting Frank Thomas and Robin Ventura and acquiring Paul Konerko. From 2001 to 2004, he was general manager of the Dodgers. He’s also worked for the Cubs, Mariners and Blue Jays and now, at age 61, runs Evans Baseball Consulting, which had an influential role in making this year’s MLB at Field of Dreams game happen. His has been a long and fruitful baseball life.

And it all started with what was no ordinary internship.

Quite quickly, Evans found himself immersed in the club’s decision-making processes. In La Russa, who was then already in his third season of managing at just 36 years old, he found a mentor and a friend. The two were close enough in age and aligned enough in interest (La Russa had received a law degree in 1978) to speak the same language. And the front office, led by general manager Roland Hemond, embraced the young man’s ideas.

“It was apparent to me that these were two of the best people I could possibly work with,” Evans says of La Russa and Hemond. “They included me in everything. And I wasn’t even out of school.”

With the promise of a permanent position awaiting him the moment he finished up at DePaul, Evans’ career path was forever altered. By the summer of 1982, the former intern was now a full-timer entrusted with, among other things, the club’s computer system.

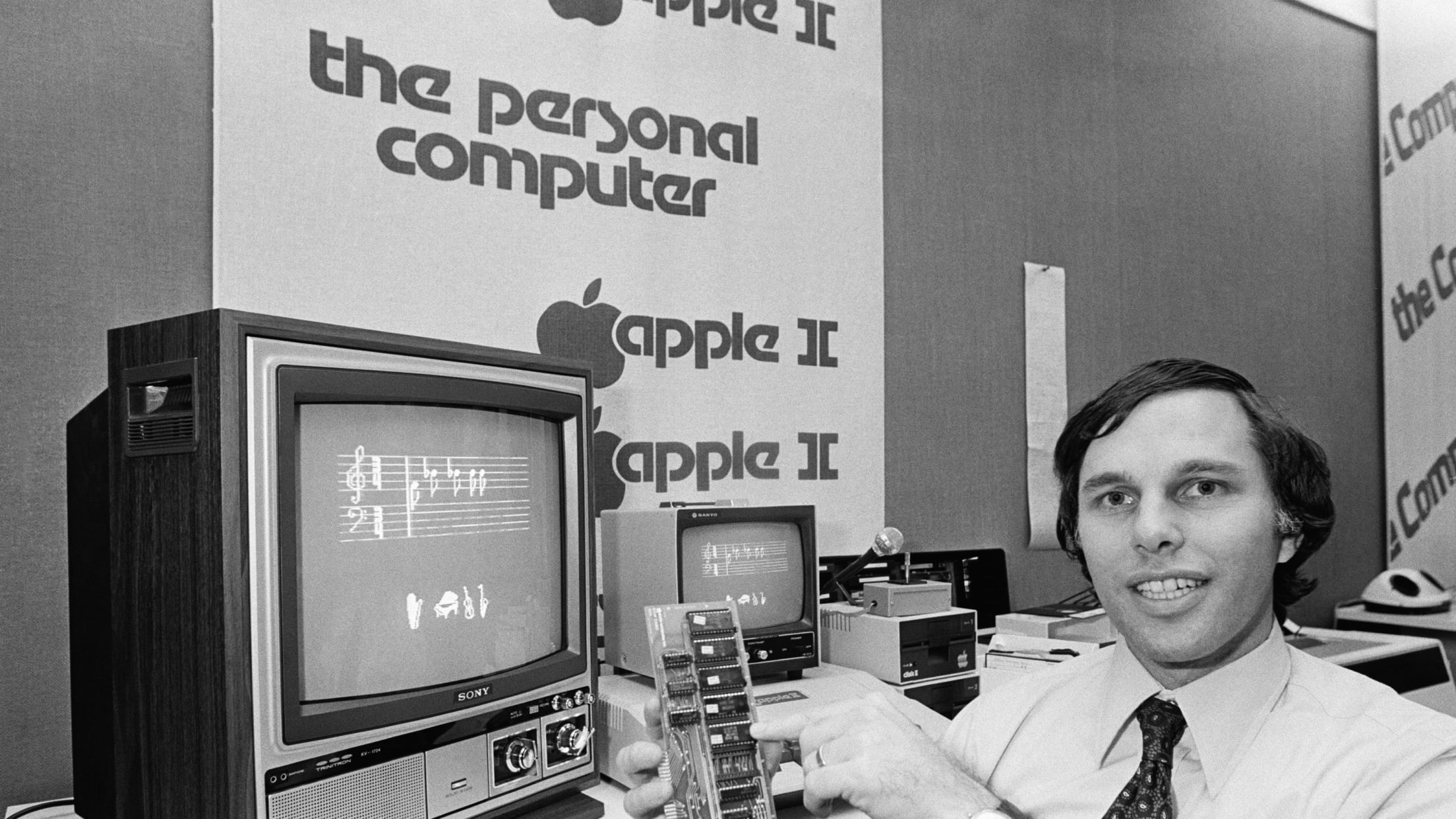

At that time, the Sox were one of two teams that had purchased a program called Edge 1.000. It was designed by Dick Cramer, a Philadelphia chemist who co-founded STATS Inc., a leading sports information provider. The Edge system provided the kind of data easily accessible on the Internet today -- stuff like pitch locations, pitcher/batter matchups, batting splits, etc. -- that can be readily referenced to determine trends and tendencies.

Like any computer program, Edge was only as reliable as its inputs. Today, we have cameras and optical tracking sensors providing the data backbone for the influential Statcast system, and we have a wealth of statistics databases automated to provide real-time updates to even the most casual fan. But back then, it was up to each purchaser of the Edge platform -- a system that cost teams $80,000 -- to have somebody tabulate the location and outcome of every pitch of every game.

Somebody like Evans.

Growing up on Chicago’s North Side in a house of divided baseball loyalties (his father was a rabid White Sox fan, while his mother loved the Cubbies), Evans became entranced by the game’s numbers. His dad taught him math by having him tabulate batting averages and ERAs at a young age. So the job with the Sox was perfect for him, even though he had never previously used a computer in his life.

Immediately after graduation, Evans began traveling with the team, lugging his Apple IIe, three floppy disk drives and a green-screen computer monitor in and out of each ballpark’s press box. It was a particularly challenging responsibility at Fenway Park, where, at the time, there was no elevator to reach the upper press level, forcing Evans to tow his load up the old concrete ramps.

People looked at the baby-faced Evans like he was nuts. Even the Oakland A’s -- the only other team to have purchased Edge to that point -- used the program primarily to generate interesting statistics for their broadcasts. The Sox had a higher aim. They were looking for numbers that would give them, as the program’s name implied, an edge.

“Long before ‘Moneyball’ became popular,” says Evans, “the White Sox were the most progressive team in baseball, no doubt.”

La Russa used the data generated by Edge to inform some unorthodox-but-statistically-sound lineup decisions. Evans showed him printouts suggesting that left-handed-hitting center fielder Rudy Law actually performed as well against fellow southpaws as righties, so La Russa stopped pinch-hitting for Law in those spots. The ground-ball data showed that using the left-handed Mike Squires at third base would not be defensively damaging, so La Russa defied convention by having Squires make a few starts there. La Russa and pitching coach Dave Duncan, whose own advance-scouting notes and charts changed the way pitchers prepared and defenses aligned in that era, would listen as Evans described the effects of inward winds at Comiskey on the Sox’s fly-ball-oriented pitchers, and it would influence their pitching decisions.

“We were information fanatics,” La Russa says. “I had to do it because I was such a lousy player and had so little experience.”

Not all of this data was presented to the players. Baseball clubhouses were not yet ready for the intellectual invasion that would one day consume the sport. But La Russa and his coaching staff, the front office and ownership were forward-thinking and open-minded enough to welcome what the computer and the whiz kid running it had to offer.

And never were they more open-minded than the day Evans suggested that the best way to tap the White Sox’s potential was to dramatically alter the oldest ballpark in Major League Baseball.

* * * * * * * *

Longtime White Sox groundskeeper Roger Bossard remembers his reaction:

“Really?”

Comiskey’s field was -- and is -- in Bossard’s blood. His dad, Gene, had been the ballpark’s head groundskeeper since 1940, and Roger worked with him as an assistant in 1967 before replacing him when he retired in 1985. Known as “The Sodfather,” Roger is still the head groundskeeper at the Sox’s home at Guaranteed Rate Field to this day.

So for father and son, that Comiskey sod was sacred. They had spent countless hours treating it, trimming it, tending to its nuances and needs. They would also work with the Sox infielders to perfect the area at their particular positions, tailoring their rake strokes to each player’s personal dirt desires.

Groundskeepers are relentless perfectionists by nature. The ballfield is their baby, and they will do whatever they can to protect it. When thousands of unruly fans at “Disco Demolition Night” famously trampled Comiskey’s turf and built a bonfire of vinyl records in the outfield grass in 1979, Roger and Gene had locked themselves in the clubhouse as a matter of self-preservation and then, around 2 o’clock in the morning, come out to begin the arduous task of repairing what the rioters had ruined.

Even that, though, was a simpler process than what was being proposed late in the 1982 season. The White Sox brass had looked at the numbers spit out by the computer system and decided to make the notoriously cavernous Comiskey more homer-friendly.

And the way they wanted to do that was to physically move the field, not the fences.

“It’s not a groundskeeper’s dream,” Bossard says with a laugh.

But to the Sox, it made sense.

The first thing is the foul poles -- those old, yellow, steel foul poles that run up 200 feet. You’ve got to bring the cranes out, take them off and get your sight lines right. Then it’s irrigation lines, drainage lines, the whole bit. You have to strip the sod, dig out the [pitcher’s mound] clay and move it to the back part of the infield, put in new drain tail, move irrigation lines … It was a job. A huge job.

White Sox groundskeeper Roger Bossard

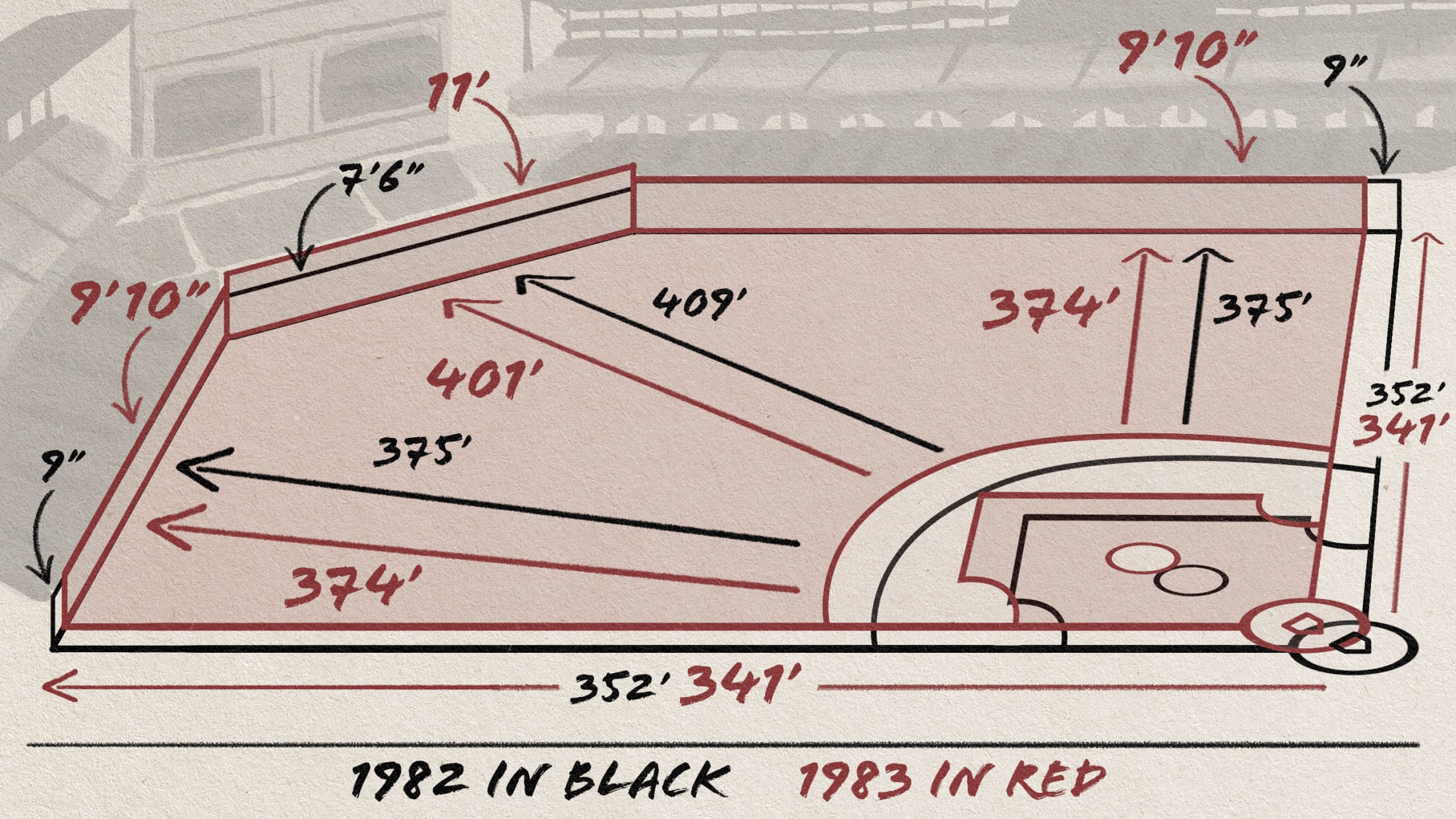

Evans’ data on the fly-ball tendencies of the club’s hitters and pitchers (which he checked and double-checked and checked again to be sure) suggested that, if the Sox could position their hitters just eight feet closer to the fences, the offense would benefit dramatically, while the impact to the pitching staff would be minimal.

“Our ballclub in ’83 was going to be essentially the same club as ’82,” Evans explains. “So we kind of knew the personnel. We had the ground-ball/fly-ball data. We knew our pitchers and hitters and how they fared. Today, we take that for granted. You just go to FanGraphs and get all that information. But back then, it wasn’t easily retrievable. We were one of the few teams, if not the only team, that had that data.”

Evans ran the data by the higher-ups. Everybody bought in. But as sure as they were about decreasing the home run distance, the Sox were equally sure that simply moving the fences in -- as the Marlins and Giants did recently and as many teams have done in the past -- was a non-starter.

For one, Comiskey’s outfield fence was made of concrete. It wasn’t going anywhere. And while temporary fencing at a shorter distance had been erected as recently as 1969 (and taken down in 1970) ownership did not want to disrupt the ballpark’s aesthetics.

“When we had this little 6- or 8-foot chain-link fence, it was brutal-looking,” Bossard recalls. “Eddie [Einhorn] and Jerry [Reinsdorf] had just bought the team. They didn’t want that.”

So the best option was to move the field itself. Per an infographic from the Chicago Tribune at that time, the newly drawn-up dimensions shortened the distance to the center-field wall from 409 feet to 401 feet. The distance to the outfield corners was shortened from 352 feet to 341 feet, and the distance to the power alleys was shortened from 375 feet to 374 feet.

To prevent a truly dramatic shift in the style of play at Comiskey, the fences would be raised. The straightaway center-field fence was extended from 7 feet, 6 inches to 11 feet, and the wall in the corners was raised from 9 feet to 9 feet, 10 inches.

Of course, anybody can put all that on paper.

It was up to Bossard’s 10-person crew to bring it to life.

“It’s not just moving the plate and the mound,” Bossard says. “It’s a huge undertaking. The first thing is the foul poles -- those old, yellow, steel foul poles that run up 200 feet. You’ve got to bring the cranes out, take them off and get your sight lines right. Then it’s irrigation lines, drainage lines, the whole bit. You have to strip the sod, dig out the [pitcher’s mound] clay and move it to the back part of the infield, put in new drain tail, move irrigation lines… It was a job. A huge job.”

The job began when the 1982 season ended. First, the Sox had wind studies conducted to confirm the effects moving the plate and mound forward eight feet would have on fly balls. Once the results matched what Evans’ data suggested, it was time to start digging.

One day that fall, Evans got off the CTA train at the rapid transit station on West 35th Street. As he made the short walk to work, he saw a big mobile crane going through Comiskey’s elephant doors.

“Oh my God,” Evans thought to himself, “they’re actually doing this!”

* * * * * * * *

When Reinsdorf and Einhorn bought the White Sox in 1981, one of their first orders of business was a renovation project for Comiskey Park that included sky box luxury suites, premium seating near the infield and a state-of-the-art video scoreboard capable of displaying animation, instant replays and a smorgasbord of statistics.

But while the Sox’s new owners were well-off enough to give the old building a boost, they were also wise enough to know what made it special.

So, yes, the scoreboard would still “explode.”

The so-called “exploding scoreboard” had been a signature staple of the Sox experience under previous owner Bill Veeck. When a Sox player would hit a home run, the electrical monster would awaken. Multi-colored pinwheels would spin, strobe lights would flash, sirens would sound, and fireworks would light up the night sky.

When the scoreboard received a $5 million upgrade prior to 1982, those entertaining elements were enhanced, not replaced.

“The home run is the most exciting thing in baseball,” Reinsdorf told the Chicago Tribune at the time. “What better way to salute it than by fireworks?”

Alas, in 1982, the scoreboard was explosive but the offense was not. The Sox hit 51 dingers at home that season, the third-lowest total in the American League.

The first real sign that things would be different in 1983 came on May 24. That night, against the visiting Red Sox, Chicago hit a season-high five home runs, including a blast by rookie left fielder Ron Kittle that hit off the facing of the Comiskey roof and a solo shot from designated hitter Greg Luzinski that -- notably -- barely cleared the outfield wall for his fifth homer in as many games.

As the explosive evening unfolded and the Sox pounded their way to a 12-4 win, team executive Steve Schanwald remarked to Einhorn, within earshot of the legendary Chicago Tribune writer Jerome Holtzman, that the operational cost of the scoreboard features was $250 per home run.

“Oh my God, it’s costing us a fortune!” Einhorn replied in mock agony, per Holtzman’s game story. “We’re still in the third inning, and it’s cost us a thousand dollars!”

The truth is that, for as expensive as the explosions may have been, moving the field was a revenue-generator for the Sox. It allowed them to add four extra rows of box seats behind home plate -- primo seating that came at a premium price. And as the Sox became more prone to lighting up the home scoreboard, they became a bigger draw, as well as a bigger threat to win the AL West.

Chicago was a mere 16-22 after that win over Boston, mired in sixth place. But by the All-Star break, the Sox were three games over .500 and within 3 1/2 games of the first-place Rangers.

That year’s All-Star Game was held at Comiskey -- a 50th anniversary celebration of the first Midsummer Classic, which had also taken place there. Fred Lynn’s third-inning grand slam in the AL’s 13-3 victory remains the only grand slam hit in an All-Star Game. It traveled several rows into the right-field seats, so it was no wall-scraper. But because the change to the field affected the wind patterns and the flight of fly balls at Comiskey, we can at least entertain the idea that the field’s reconstruction may have had a role in that bit of baseball trivia.

And even if not, it certainly had an impact on the ’83 Sox.

“Eight feet made a big difference,” Bossard says. “It was just huge.”

The Sox stormed up the standings in the second half, seizing first place for the first time on July 18 and never letting go. They finished 99-63, 20 games ahead of the second-place Royals.

“That was the first time there had been winning baseball in Chicago in a long time,” La Russa recalls. “So every time we’d lose a game, people would say, ‘Oh, here it comes …’ But our guys killed it in August and September.”

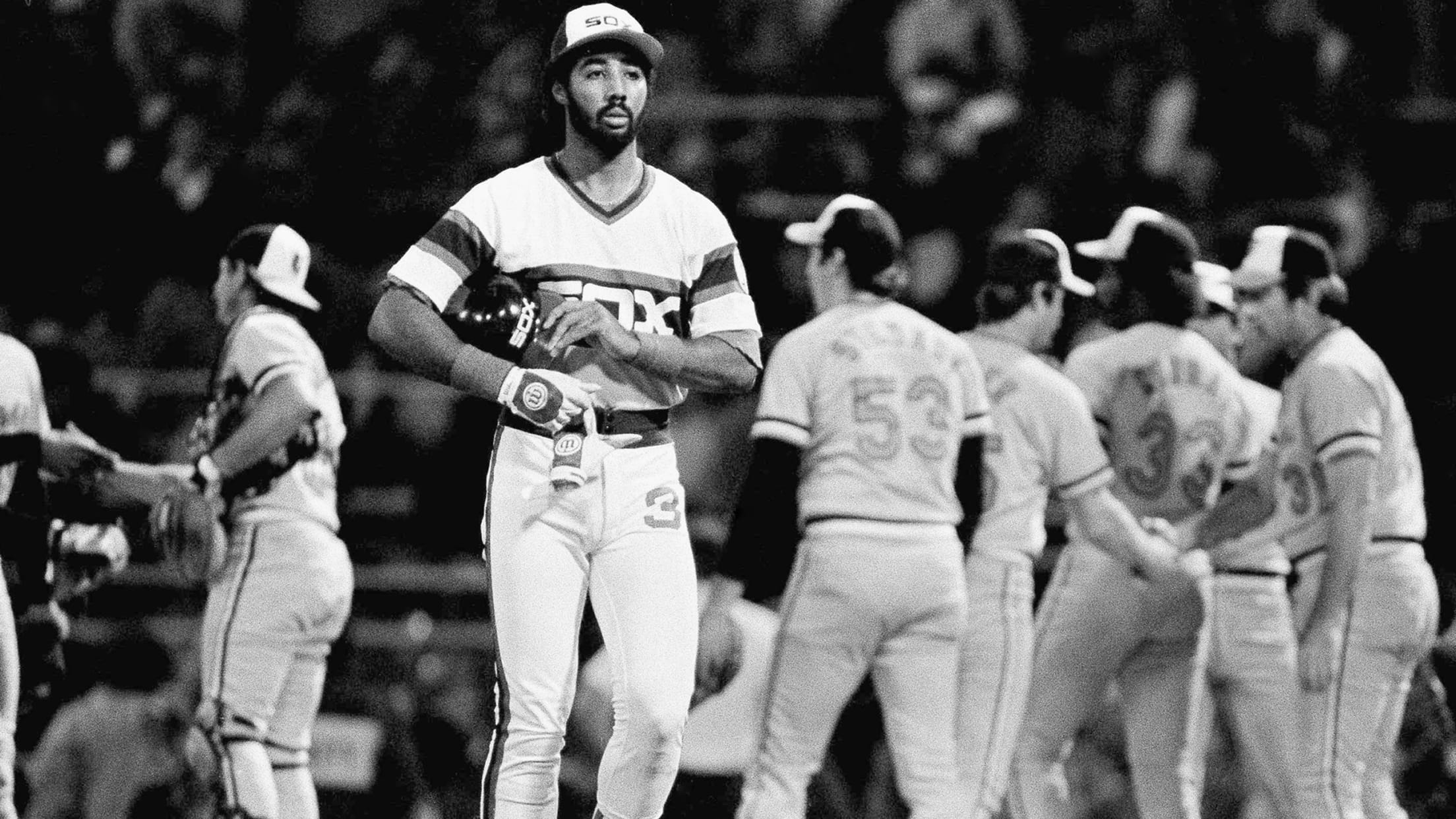

A 99-win team does not succeed on the long-ball alone. The ’83 Sox were known for “winning ugly,” as Rangers manager Doug Rader put it. They wore those tri-colored hats, pants with uniform numbers and license-plate-looking pullover jerseys with big blocks of color and chunky typeface. They had the AL Cy Young winner in LaMarr Hoyt, the Rookie of the Year in Ron Kittle and the Manager of the Year in La Russa. They had two future Hall of Famers in Baines and catcher Carlton Fisk. They had a fantastic coaching staff featuring Duncan, bench coach Ed Brinkman, hitting coach Charley Lau, first-base coach Dave Nelson and third-base coach Jim Leyland. They had the second-best rotation ERA in the league. They were a damn good team.

But it’s impossible to ignore the impact the homer help played.

In 1982, a similar Sox lineup (albeit mostly sans Kittle, who was a September callup) went 52.5 at-bats between home runs at Comiskey -- the third-worst rate in the AL.

In ’83, the Sox went just 31.7 at-bats between home runs in their home park -- the second-best rate in all of MLB. Their 84 home runs at Comiskey were the second most in the building’s long history.

This improvement didn’t come completely without a cost. Sox pitchers that had surrendered 0.53 homers per nine innings in ’82 served up 0.78 per nine in ’83. But that was a small price to pay for the power improvement of the home offense.

To my grandmother, it was her hallowed grounds being messed with. I remember telling her about the plans, and she wasn’t very happy. But she called me one day that summer, very late at night, and said, ‘I didn’t like the idea. But it sure seems like your hitters like it.’

Dan Evans

And while the changes to the field were aimed at giving the Sox help on those fly balls that had once died at the warning track, they also had an awe-inspiring effect on some of the no-doubt blasts that once went to the upper deck and now landed on the roof. The previous decade had seen just three homers reach the roof, with none since 1977. But in ’83 alone, there were five roof shots, all by the Sox’s two bespectacled sluggers -- three by Luzinski and two by Kittle.

“We could do some damage,” Kittle says now.

Kittle’s 35-homer season that earned him Rookie of the Year featured 18 homers at home and 17 on the road, so he was no Comiskey creation. But generally speaking, the power surge the Sox experienced between 1982 and ’83 did not translate on the road. While their 73 road dingers were tied for the fifth most in MLB in ‘83, their number of at-bats between road home runs actually increased, from 34.1 in ’82 to 38.7 in ’83. It was the Comiskey effect that had altered their offensive existence.

Perhaps, as La Russa contends, the weather played a role, too. That was a hot summer in Chicago, with 42 days registering 90 degrees or higher.

“It was warmer and the wind was blowing out to left,” he says. “Balls were carrying, you know, balls were on the roof. Every day we played, virtually, it was warm and windy.”

But there’s no denying that Evans’ data had translated.

“From the keyboard,” Evans says, “to the scoreboard.”

And to the turnstiles. The Sox drew more than 2.1 million fans that season, a 36-percent increase from the previous year and a new Comiskey record. The change to the field even won over perhaps the most skeptical Sox fan of all -- Evans’ grandmother, Dorothy.

“To my grandmother, it was her hallowed grounds being messed with,” Evans says. “I remember telling her about the plans, and she wasn’t very happy. But she called me one day that summer, very late at night, and said, ‘I didn’t like the idea. But it sure seems like your hitters like it.’”

Alas, the magic ran out for the ’83 Sox in the AL Championship Series, when they were convincingly beaten in four games in the best-of-five by an Orioles team that went on to win the World Series.

The most notable homer at Comiskey in that ALCS was hit not by a Sox player but by O’s slugger Eddie Murray, who launched a three-run blast into the second deck in an 11-1 thumping in Game 3.

“Well, you didn’t have anything to do with that one,” Dorothy Evans told her grandson after the game. “That ball would have been out of Yellowstone!”

* * * * * * * *

If Bossard wasn’t thrilled with the prospect of digging up his beloved ballfield in 1982, you can only imagine how he felt about the order that arrived just three years later:

The White Sox were moving home plate back.

In October 1985, Ken Harrelson was named the club’s executive vice president of baseball operations. By the end of his first season at the helm in ‘86, Hemond, who had been reduced to a special assistant role, had left the team, and La Russa and Hemond’s assistant GM, Dave Dombrowski, had been fired.

“The Hawk,” therefore, obviously proved open to change. And the first change he had demanded was that Comiskey return to its old dimensions.

''It won’t affect our guys,'' Harrelson told reporters at the time. ''When Harold Baines, Carlton Fisk, Ron Kittle and Greg Walker hit 'em, they go out. What I'm trying to prevent are guys like Marty Barrett of Boston and Mike Gallego of Oakland and Rich Dauer of Baltimore from leaving our yard. They've hurt us before with homers. I don't want to see them hurt us again.''

Harrelson had a point. The rise in opponent home run rate that was manageable for the Sox in ’83 had become more pronounced by ’85. Opponents hit a home run every 34.1 at-bats at Comiskey in ‘85, bettering the Sox hitters’ rate of one every 35.7 at-bats.

The Sox had made the field change in ’83 because of data tailored to their team at the time. By the fall of ‘85, however, the team complexion had changed enough that the old data no longer applied.

So Bossard and his crew dug up home plate and went back to work.

“Oh boy,” he thought, “here we go again.”

Comiskey’s data-altered dimensions might not have lasted, but Evans’ idea aided one of the most special seasons in franchise history. In ’83, the White Sox made the playoffs for the first time in Evans’ lifetime, and La Russa reached October for the first time in what would turn out to be a Hall of Fame career.

“You can ask any manager,” he says. “The first one is special. You never know if you can help pull it off, so the first one is special.”

Here in 2021, La Russa is headed to the postseason for the 15th time, one shy of Bobby Cox’s all-time record. That he’s again doing it with the White Sox makes Evans smile.

“The way he embraced a junior in college when he was a big league manager told me there was no way he’d fail in that role,” Evans says. “The best thing about Tony is you could throw any idea out there and not be humiliated. There were no bad ideas. You just had to base them with facts.”

As Evans can attest, sometimes the wildest ideas become reality.