The L.A. Browns? How one day in '41 changed MLB

In the second week of the final month of 1941, the owners of the Major League ballclubs convened at the Palmer House in Chicago for the Winter Meetings. Among other business, they were expected to take a vote that would completely remake the continental footprint of Major League Baseball and change the course of sports history.

The St. Louis Browns were seeking approval to head west to Los Angeles.

The long-struggling Browns -- the team you know today as the Baltimore Orioles -- had given up on Missouri. Unable to compete in the American League on the field or with the rival Cardinals off of it, Browns ownership had decided to move the team to Los Angeles for the 1942 season, becoming the first major American professional sports franchise on the West Coast.

The Browns had preliminary approval from the other owners. They had funding promises from A.P. Giannini, the California-based co-founder of Bank of America. They had a Minor League ballpark ready to use at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field, and an agreement to enlarge it. They'd handled territorial issues by agreeing to purchase the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League -- who would move south to Long Beach, Calif., as the top Browns farm club -- and acquire several of their best players as well, like pitcher Jesse Flores, who would throw 231 1/3 innings with a 3.11 ERA for the Philadelphia A's in '43, and "Jittery Joe" Berry, who would put up a 1.94 ERA in 111 1/3 innings for the A's in '44.

They had worked with the head of TWA Airlines and the operators of the Chicago-to-Los Angeles Santa Fe Railroad to hammer out a schedule with the AL office that satisfied the considerable travel concerns. Even the Cardinals were on board -- owner Sam Breadon had offered the Browns $250,000, or more than $4 million in today's money, to simply get out of town.

Browns owner Donald Barnes was quoted in the St. Louis Star-Times that month, sounding confident about the viability of Los Angeles:

"There has been considerable talk about taking one club out of St. Louis. I consider Los Angeles the most desirable city for a Major League team. Transportation problems could be solved through air travel."

The Browns were so certain they were moving that they had even set up a news conference in Los Angeles at Lyman's Cafe. All they needed was for the official vote, which was expected to pass. The Browns would head west, more than 15 years before the Dodgers and Giants ended up doing so.

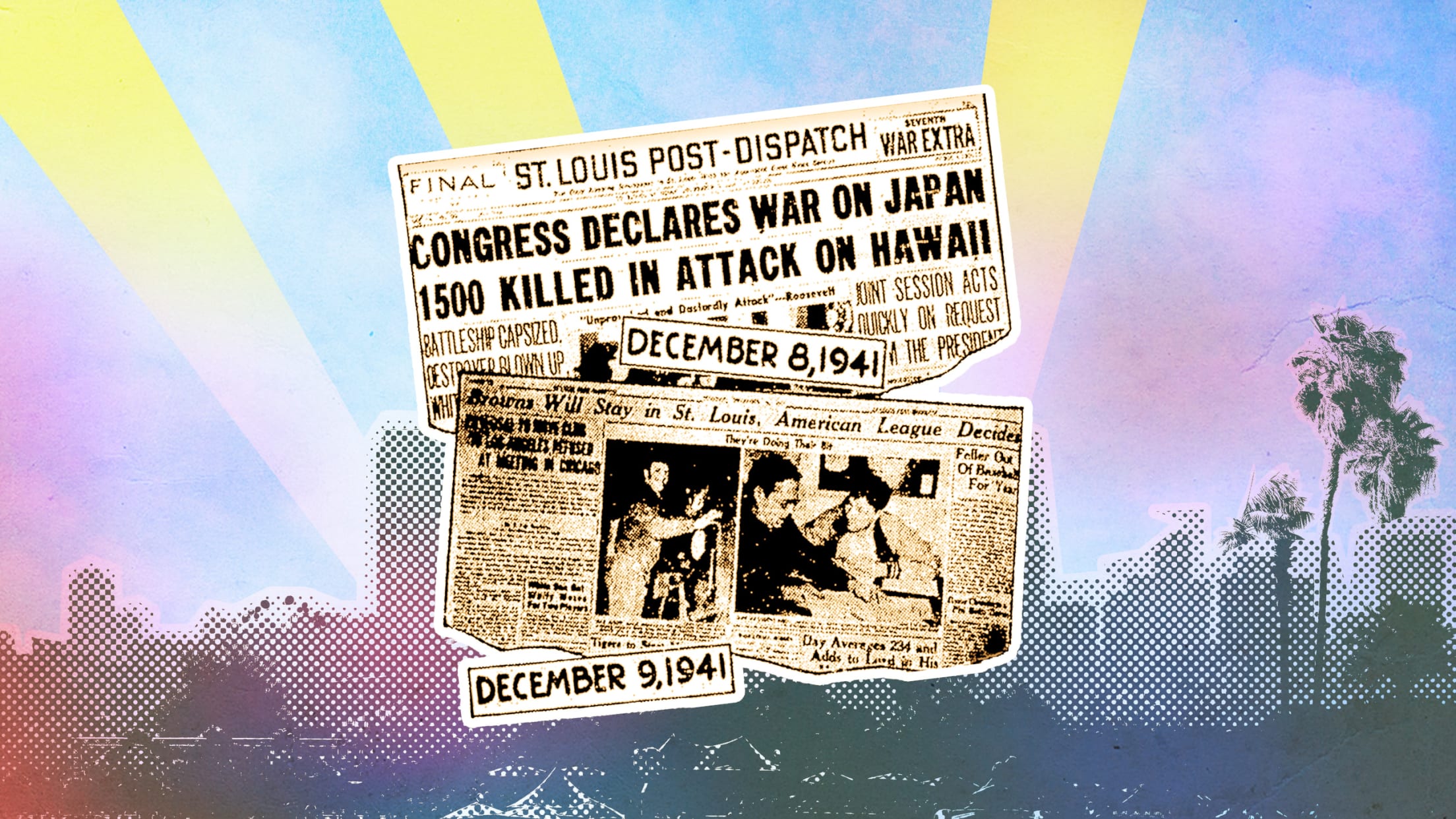

And so, the vote was scheduled. It was to take place in Chicago on the morning of Monday, Dec. 8, 1941. The news conference in Los Angeles was scheduled for 1 p.m. PT the same day. The Browns would triumphantly introduce themselves to Southern California. Major League Baseball would span coast to coast.

The vote did indeed take place. Each team voted against the move -- including the Browns. If you know anything about American history, you know what had happened. The Browns would remain in St. Louis. Baseball wouldn't arrive in California until 1958.

The night before, while Browns owners were at Comiskey Park in Chicago watching the NFL's Bears beat the Cardinals, 34-24, and eagerly anticipating the next day's presumed success, word reached the continental United States about the attack on Pearl Harbor, and America's subsequent entry into World War II. Quickly realizing the timing clearly wasn't right to move a team 1,800 miles west, Browns ownership reversed course on the plan. The Browns stayed in St. Louis for another dozen years, eventually moving to Baltimore following the 1953 season to become the Orioles.

But ... what if they didn't? What if the vote had happened before Pearl Harbor, and it wasn't rescinded? Or a mere one season sooner? Or if Japan had attacked later, or never, or if America had never entered the war at all? What if -- much like the fact that the National League doesn't have the designated hitter is entirely because of one ill-timed 1980 fishing trip -- this one single thing had gone differently? The Browns wouldn't be the Orioles, and they wouldn't be in Baltimore. They'd be nearing their 80th anniversary in Los Angeles, and the butterfly effect of that one single change would render baseball history almost unrecognizable compared to what we know today. Nearly half the teams in baseball might call different cities home.

Let's lean into the chaos theory and play this out. If the vote had been scheduled for Dec. 1 rather than Dec. 8, and the wartime circumstance didn't render it void ... what does that timeline look like?

1942

Fantasy: The Browns rule Los Angeles.

Reality: A country at war stalls St. Louis' move west.

Yes, it's possible they would have been called the "Stars" or "Angels" or another name with an established baseball history in Los Angeles, but we'll stick with "Browns" here, much as the Dodgers and Giants kept their names. They'd have beaten the NFL's Rams to Southern California by four years, and the NBA's Lakers by 18. They'd have been the first to some incredibly fertile new ground. You've seen how successful the Dodgers have been over the years, right? This could have been a massively prosperous franchise.

It's true that the Browns wouldn't have arrived with Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale on their roster as the Dodgers did -- though the '41 Browns did have 20-year-old shortstop Vern Stephens, a Long Beach native who would become an eight-time All-Star and hit 39 homers in '49 -- and they wouldn't have come with the social currency of having been the team of Jackie Robinson. Vin Scully wouldn't have been the voice of generations of California kids. It wouldn't be exactly the same. It wouldn't be the same at all.

But with the massive Los Angeles market all to themselves, the reborn Browns become a baseball powerhouse:

• When Don Larsen throws baseball's first and only postseason perfect game in the 1956 World Series, he does so at Browns Stadium in Los Angeles, having remained with the team that signed him as an amateur in 1947.

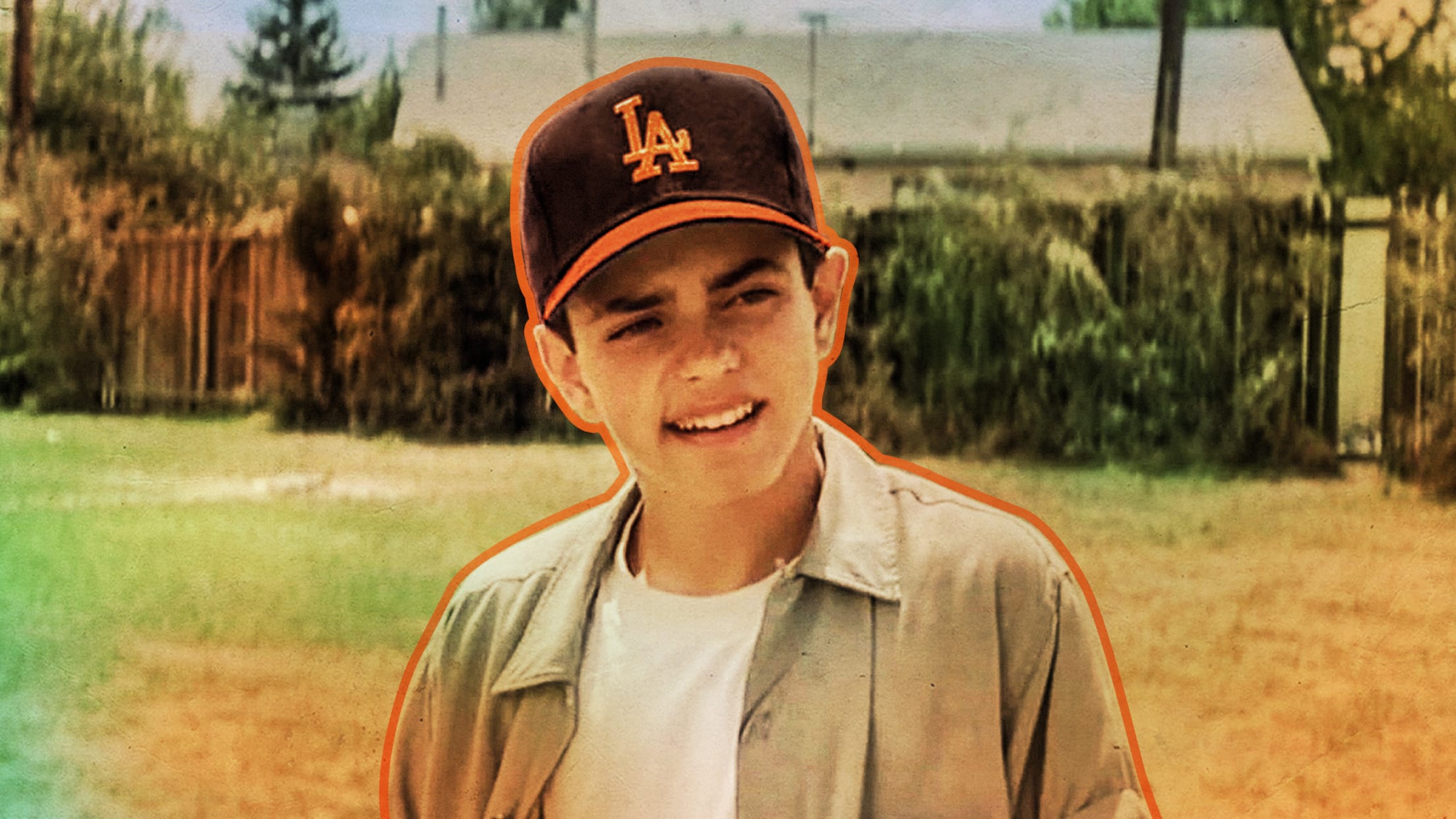

• Children all over the Southern California area grow up wearing brown and orange. Decades later, when the beloved movie The Sandlot is made in 1993, Benny "the Jet" Rodriguez is seen wearing a Browns hat, as he dreams of growing up to represent his hometown Brownies.

• The Brown Derby is thrilled with the sponsorship opportunities, though occasional attempts to model the team's caps after the ubiquitous restaurant chain have offered mixed results at best.

The Browns, for going on more than three-quarters of a century now, have been regarded as one of baseball's crown jewels, spoken of in the same breath as the Yankees, Cubs, Cardinals and Red Sox.

1948

Fantasy: The Philadelphia A's move to the Bay Area.

Reality: Family ownership squabbles lead to a 1955 move to Kansas City.

In real life, the Brooklyn Dodgers convinced the New York Giants to move west to California with them, largely in order to have a rival on the coast to cut down on travel costs. Our Browns have had to suffer with travel for their first few years -- partially by train, occasionally by air, but lots of three-week road trips -- and it quickly becomes clear they need a partner. Given their wild California success, it's not difficult to find one. (In the days before Interleague Play, it has to be an American League team.)

Enter the Philadelphia Athletics, who, like the Browns, were the second team in a two-team town that only needed one. The real A's moved to Kansas City in 1955 and then Oakland in 1968, but we're skipping a step, and adding a few miles. The Macks, longtime owners of the team, sell to San Francisco businessman Paul Fagan, who'd purchased the Pacific Coast League's San Francisco Seals in 1945 and spent millions upgrading their stadium with the express purpose of placing a Major League team there. In our fantasy world, that gamble pays off.

Like the Browns, the A's prosper as the main draw in their bustling new home:

• With no need to serve as an unofficial "farm team" to the Yankees, as the Kansas City A's did for much of the '50s, the San Francisco A's hang on to young players like Roger Maris, who will make a few All-Star teams, but doesn't break any homer records, and otherwise has a solid-yet-forgettable career in the blue and red. (The real A's didn't don green and gold until halfway into their Kansas City tenure, the brainchild of Charlie O. Finley.)

• After some time at the old Seals Stadium, the A's spend decades at Candlestick Park, before moving into a beautiful jewel of a ballpark on San Francisco Bay, the envy of all those who see it.

There's appeal to this timeline, apparently.

We'll let the Boston Braves move to Milwaukee in 1954 as they actually did, and then ...

1954

Fantasy: Willie Mays returns to Minnesota a hero.

Reality: Mays makes arguably the most memorable play in history.

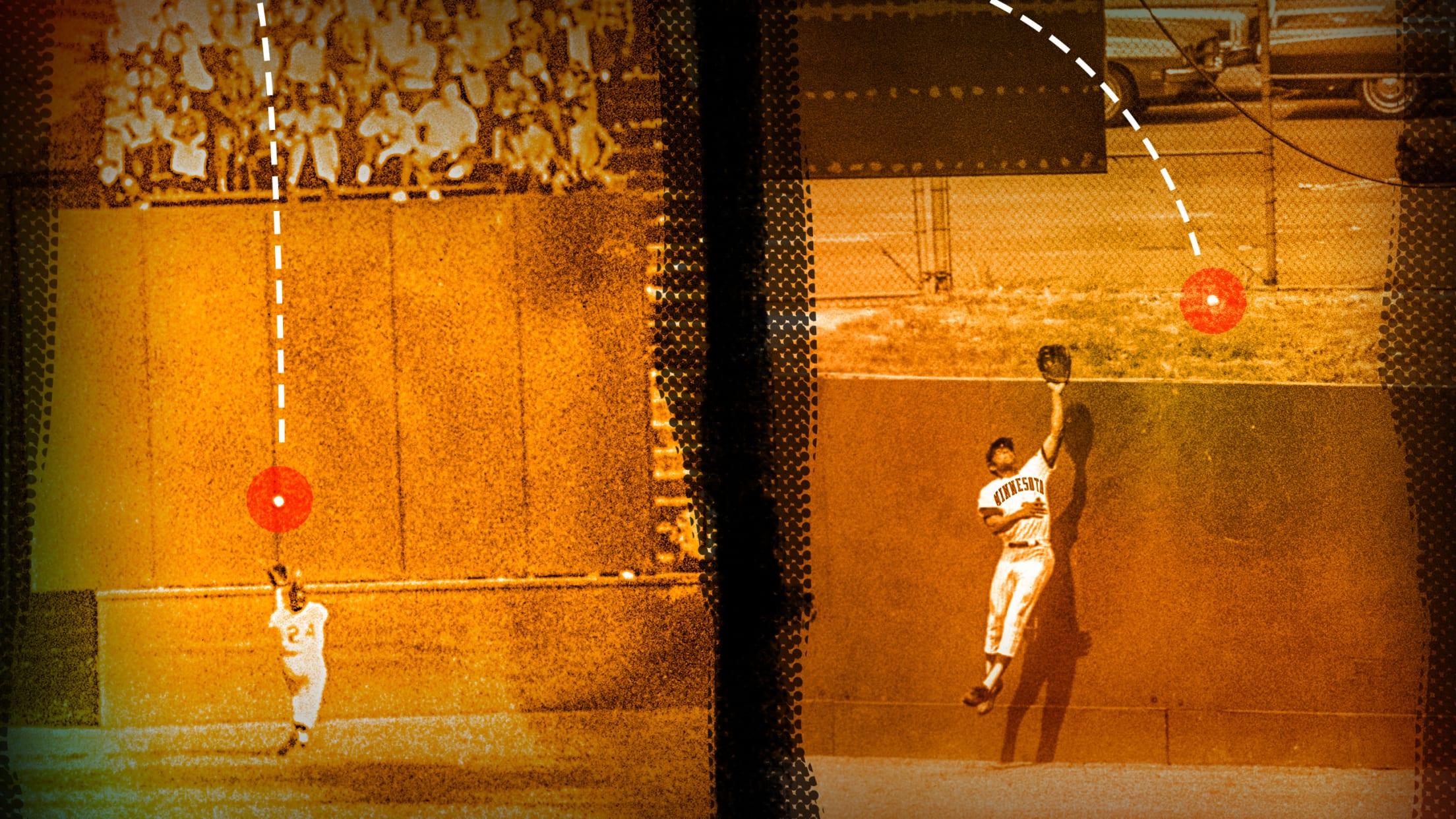

As we just noted, the real Giants moved to San Francisco at the behest of the Dodgers, but they had to be talked out of their original plan: Moving to Minneapolis. Giants ownership also owned the Triple-A Minneapolis Millers, which under the rules of the time gave them the rights to Major League Baseball there, and team owner Horace Stoneham owned land in the area. Mays had actually played for the Millers in 1951, hitting so well -- a ridiculous .477/.524/.799 in 35 games -- that the Giants formally apologized to Minnesota fans for taking him away from them.

With the Dodgers obviously not dragging them out west, the Giants go forward with the move to Minnesota in our alternate timeline, and in the process, they bring Mays back to the fans he'd been forced to leave several years earlier. The first time around, he'd lived at 3616 Fourth Avenue South. After 17 more years in the Twin Cities, he lives forever in the hearts of Minneapoleans.

That said, when the Giants make it to the World Series in '54, they do so in Metropolitan Stadium, which in reality was completed in '56 but gets bumped up slightly for our purposes. When Cleveland's Vic Wertz came up in the eighth inning of a 2-2 tie in Game 1 of the World Series, his deep blast to center field goes for a three-run homer, giving the Indians the win and the momentum to take the Series, marking the 111-win World Series champion 1954 Tribe as one of the greatest teams of all time.

It's fun to think of what might have happened if, say, Wertz had hit that ball in a park with absurdly deep dimensions -- like, say, the Polo Grounds in New York, which was 483 feet to dead center -- the speedy Mays might have been able to make a play that would have been one of the most enduring in baseball history, one so notable that today it would be known as merely "The Catch." That, however, is speculation and hyperbole. It's another timeline entirely. This flag flies forever in Cleveland.

1958

Fantasy: Sandy Koufax and Vin Scully head to Texas.

Reality: Sandy Koufax and Vin Scully head to California.

Just because the Giants left New York earlier doesn't mean that the Dodgers, as New York's sole remaining National League team, have all their problems disappear. Ebbets Field was still outdated and unworkable, and polarizing New York City public official Robert Moses was still only offering land in Queens, where today's real-world Mets now play. Queens not being Brooklyn, Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley fled to the West Coast in the reality we know.

That stadium issue held constant here, as well, but with the Browns well-established in Los Angeles, O'Malley doesn't want to be a second fiddle in another town. Instead, in our hypothetical timeline, he takes his Dodgers to another fresh new ground for baseball: Texas, specifically Dallas, where O'Malley and the Dodgers had owned the Minor League Fort Worth Cats since after the war. (In real life, he swapped them as part of a deal for the rights to Los Angeles.)

The Dallas Dodgers -- no, that name makes no sense, but neither does Los Angeles Dodgers if you really think about it -- enjoy immediate success, thanks to Koufax, Drysdale and eventually the larger-than-life Tommy Lasorda, who fits in perfectly in Texas. To this day, Scully is the voice of Texas sports, and as a bonus, their first-round pick in 2006 grew up cheering for his hometown team: the pride of Highland Park High School in north Dallas, Clayton Kershaw.

1961

Fantasy: The Angels are born into the National League.

Reality: The Angels are born into the American League.

Baseball went through heavy expansion in the 1960s, and that still happens here. In the real '61, the Angels arrive, as the AL wants to get a foothold in Southern California and to fight off the proposed Continental League. Since the AL has been there for two decades already, when Gene Autry's new team arrives, it does so in the NL. The good news is that decades later, they still draft Mike Trout. The bad news is that without the designated hitter, Shohei Ohtani chooses the Browns instead. The we'll-leave-it-up-to-you news is that without the DH, Albert Pujols signs elsewhere after leaving the Cardinals.

Every year, then, the Dodgers make three trips to Los Angeles as the visiting team, plus a fourth whenever they visit the Browns in Interleague Play.

1966

Fantasy: Atlanta gets a team from Washington, D.C.

Reality: Atlanta gets a team from Milwaukee.

Meanwhile, there's still a Senators problem to deal with. In reality, the team best known for being "first in war, first in peace and last in the American League" moved to become the Twins in 1961. But in this alternate timeline, the Giants beat them to it, and so the struggling Senators had to look elsewhere. They looked south to Atlanta, which had been booming in the post-war era.

Earl Mann, long the owner of the Southern League's Atlanta Crackers, was known as "Mr. Atlanta Baseball," and had been looking to bring big league ball to the South for years. (He'd actually been rumored to be trying to buy the Browns way back in 1941; while he denied it, he did say "I am in the market for a big league ballclub, but not the Browns." Whether that was a denial of the rumor or a mild dig at a team that had finished sixth or lower for 10 straight seasons is up to you.)

In reality, Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. had ordered what would be called Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium to be constructed in 1963, before a team had even been procured. Working together, Allen and Mann extract the Senators south. The "Atlanta Senators" has a certain ring to it.

1960s

Fantasy: Lots of expansion, but in a different form.

Reality: Lots of expansion.

To balance things out, the Mets are born to bring NL baseball back to New York, just as they are now. But when they make their miracle run to the World Series in '69, they don't beat the Orioles. They lose to the Browns.

Rather than put a second Senators franchise in Washington through expansion, as happened in 1961, the American League expands to Baltimore, giving birth to the Orioles. The Houston Colt .45s still appear in 1962, soon becoming the Astros. They just do so in the AL, getting a 40-plus-year head start on the league they eventually call home in our world. Later in the decade, the quartet of expansion teams that we remember -- the AL's Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots, and the NL's Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres -- are still constructed in the same way.

The Padres, however, choose not to wear the brown that is so notable today, so as to not look too closely like their Southern California market rivals, the ... Browns. Instead, they choose the classy blue and red of the longtime Pacific Coast League Padres. There are still too many blue-and-red teams.

Meanwhile, the Milwaukee Braves remain in Wisconsin, where they continue to exist to this day. Without a desperate need to return baseball to his beloved hometown, Braves minority owner Bud Selig never takes full possession of the team as he eventually did with the Brewers, and thus never becomes Commissioner.

A brief reset.

OK, so, a lot has happened. It's 1970. Major League Baseball has expanded to two divisions in each league. The 24 teams look like this.

In the AL East, we have the Atlanta Senators, Baltimore Orioles, Boston Red Sox, Cleveland Indians, Detroit Tigers and New York Yankees.

In the AL West, it's the Chicago White Sox, Houston Astros, Kansas City Royals, Los Angeles Browns, San Francisco A's and Seattle Pilots.

In the NL East, it's the Chicago Cubs, New York Mets, Montreal Expos, Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburgh Pirates and St. Louis Cardinals.

In the NL West, it's the Cincinnati Reds, Dallas Dodgers, Los Angeles Angels, Milwaukee Braves, Minnesota Giants and San Diego Padres.

Similar? Sort of! Of the 24 teams there, only 14 exist in the same way they do in our reality. But we're not done yet.

1974

Fantasy: Washington gets its team back.

Reality: Washington almost gets its team back.

Sound crazy? This one almost actually happened. As the May 28, 1973, edition of the San Diego Union shouted, "The Padres have been sold to a group of Washington businessmen ... with the franchise being delivered to the capital at the conclusion of the current National League season." (With his team at 16-31 and 13 games out in the division, manager Don Zimmer's sense of humor remained intact: "If we're going, I hope I go.")

They modeled uniforms, appeared on baseball cards and even were listed on a tentative official 1974 NL schedule opening at home in Washington against the Phillies. They would have been called the Washington Stars. This didn't happen in reality for a variety of reasons -- mainly lease issues in San Diego and financial backing issues with the presumed new ownership -- but in our alternate world, it does, in part because our Washington has lost only one team, not two. Gwynn plays in Washington. So does Dave Winfield. Later on, Trevor Hoffman does as well. Today, that's where you can find Fernando Tatís Jr.

Yes, that means that decades later, the Expos stay in Montreal. Congrats on your 2019 World Series win.

1977 - present: Everything else unfolds as it did. Almost.

Baseball still expands to Toronto in '77, but in our world, the Pilots stay in Seattle rather than fleeing to Milwaukee. (Their original owners sold to well-heeled local interests after one season. Their uniforms are still excellent.) San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson -- the future governor of California -- had been threatening to sue since the moment the Padres broke their lease, so he's satisfied with an expansion team. An American League expansion team. (This is exactly how the Mariners and Royals really came into existence.) They'll still be called the Padres, just as the real-world Senators took the name of their departed predecessors.

In '93, Denver and Miami receive teams. In '98, Phoenix and Tampa Bay would as well. Ironically, the Tampa Bay team later considers relocating to the Oakland Coliseum, though the move never happens.

All of which makes the present-day version of Major League Baseball in 2020 look like this:

It is ... different. In some ways, it's probably inconceivable. Then again, some of what actually happened seems pretty inconceivable, too. If the Browns had moved to Los Angeles in 1942, Major League Baseball probably wouldn't look exactly as we just spelled out. But it wouldn't look exactly like it does now, either.

As Barnes, the then-former Browns owner, said to the Sporting News looking back upon the whole affair in 1957, just after learning the Dodgers and Giants would move west:

"What's so wonderful about that? The National League is running 16 years behind schedule. If you'll recall, we missed by just one day of putting American League ball -- the St. Louis Browns -- in Los Angeles for the opening of the 1942 season."

One day. One single day. All of baseball history could have looked absolutely, unbelievably, incredibly different.