Simmons a Hall of Fame renaissance man

Ted Simmons' induction to the Baseball Hall of Fame has robust support from the record book. He has the most hits in Major League history among switch-hitting catchers. His career OPS+ is higher than that of fellow Hall of Famers Carlton Fisk, Gary Carter, and Iván Rodríguez.

But to fully measure Simmons’ legacy requires a different sort of story, one that unfolded subtly over the 15,000-plus innings he caught for the Cardinals, Brewers and Braves.

While plenty of statistics classify Simmons as an all-time great, his peers rarely allude to them. Instead, they speak about his passion, his intellect, and his unwavering focus. He never coasted through a ballgame. And by all accounts, he’s riding a lifelong streak of 72 years without a perfunctory conversation.

“He got the most out of his ability because of his mental approach,” said Bill Schroeder, a teammate in Milwaukee during the early 1980s. “He outthought everyone.”

Simmons is a scholar of baseball, art, history -- and life. He earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan in 1996, nearly three decades after attending his first college class. He completed his coursework in Ann Arbor on trips to Detroit while scouting for the Cleveland Indians, because, as he said, there are certain things in life that a person is supposed to finish.

And he is willing to share his wisdom, provided the interlocutor is prepared with the right questions.

“You’d better be thinking it out for yourself,” Simmons told me earlier this year. “If you’re not taking this game real seriously and examining everything you see -- incorporating it into some form, like an essay, a notebook, or a booklet -- then you’re never going to understand baseball the way a professional should.

“If someone who is really serious about the game asks you a thoughtful question, I’m inclined to say, ‘Come here and sit down, and I’ll tell about what you’re seeing.’ If they have thought about the game, you can help to illuminate it for them.

“What I tell people, in the simplest form, is this: Anytime you see something happen on the field that strikes you as unusual, go there. Tear that situation apart, inside-out, upside-down and backwards. There’s going to be insight in there.”

To think deeply while playing freely is baseball’s essential riddle. Over 21 Major League seasons, Simmons came closer to solving it than most mortals have, before or since. He found a way for painstaking contemplation to enhance, rather than compromise, his natural athleticism.

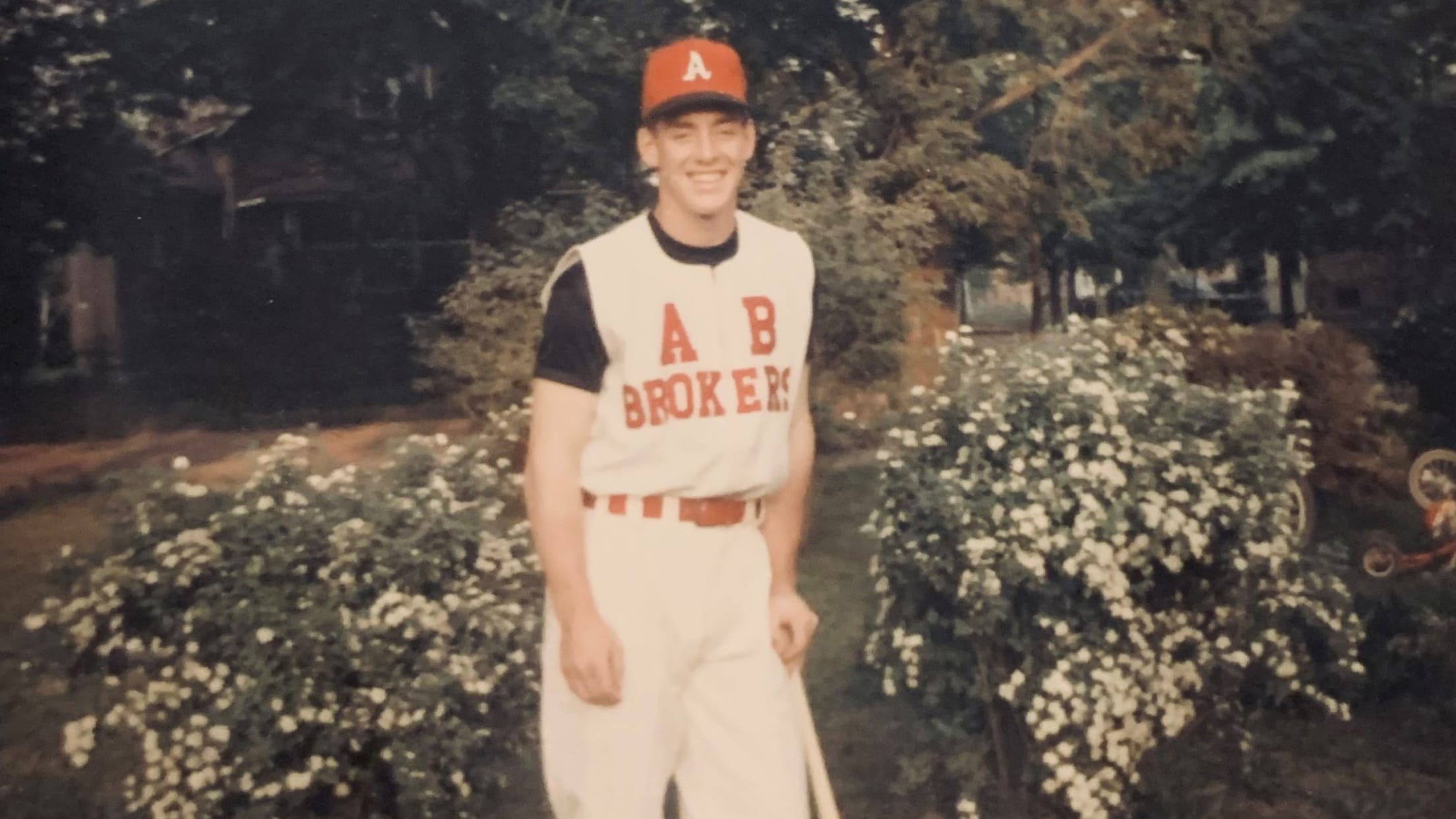

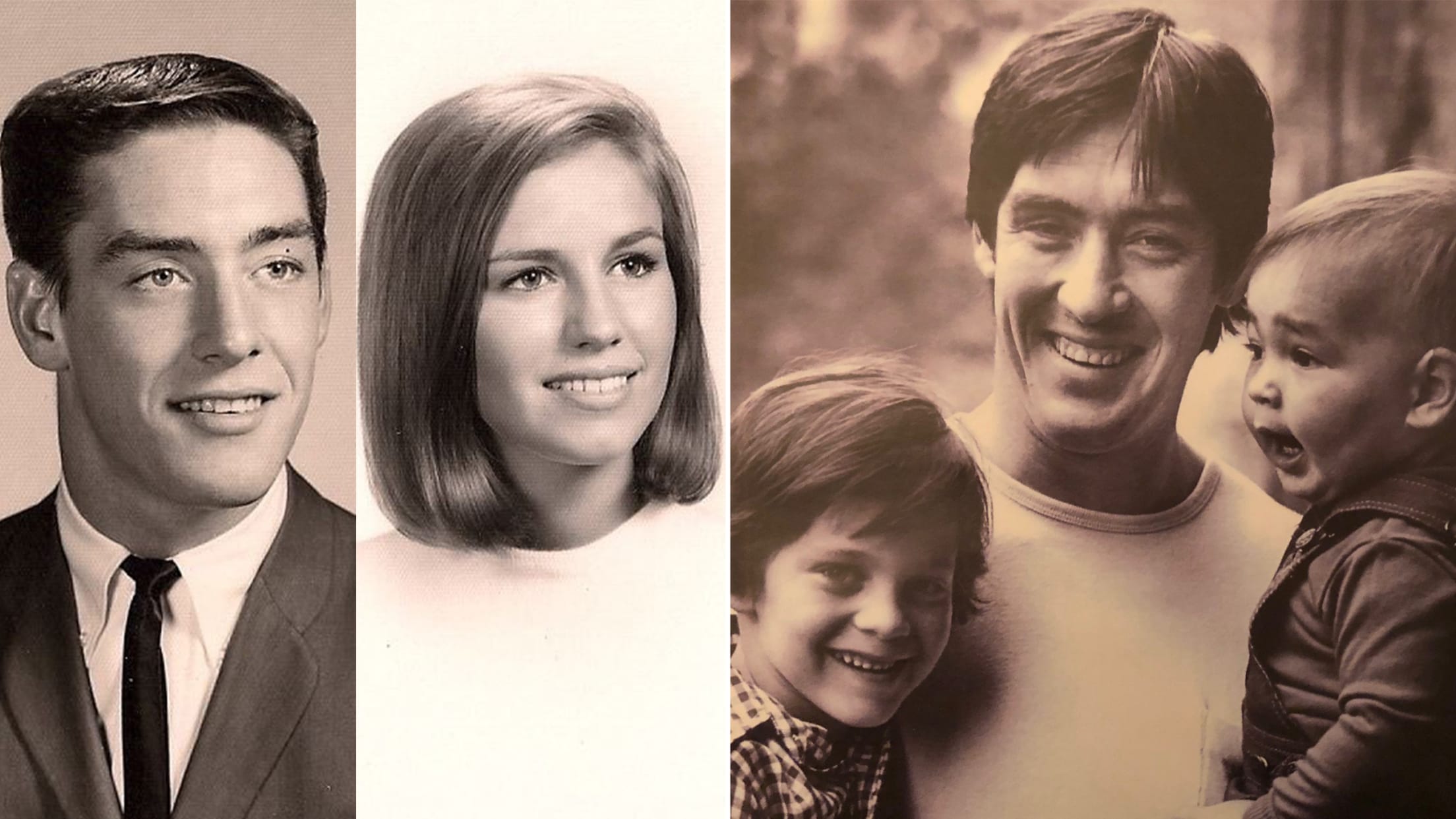

And he did it all with magnetism that was evident while growing up in the Detroit suburb of Southfield, Mich. His older brothers encouraged him to switch-hit. His mother, Bonnie Sue Webb-Simmons, modeled the determined work ethic that became the backbone of Ted’s career. He drew attention as a Big Ten football recruit while starring for the A&B Brokers amateur baseball team.

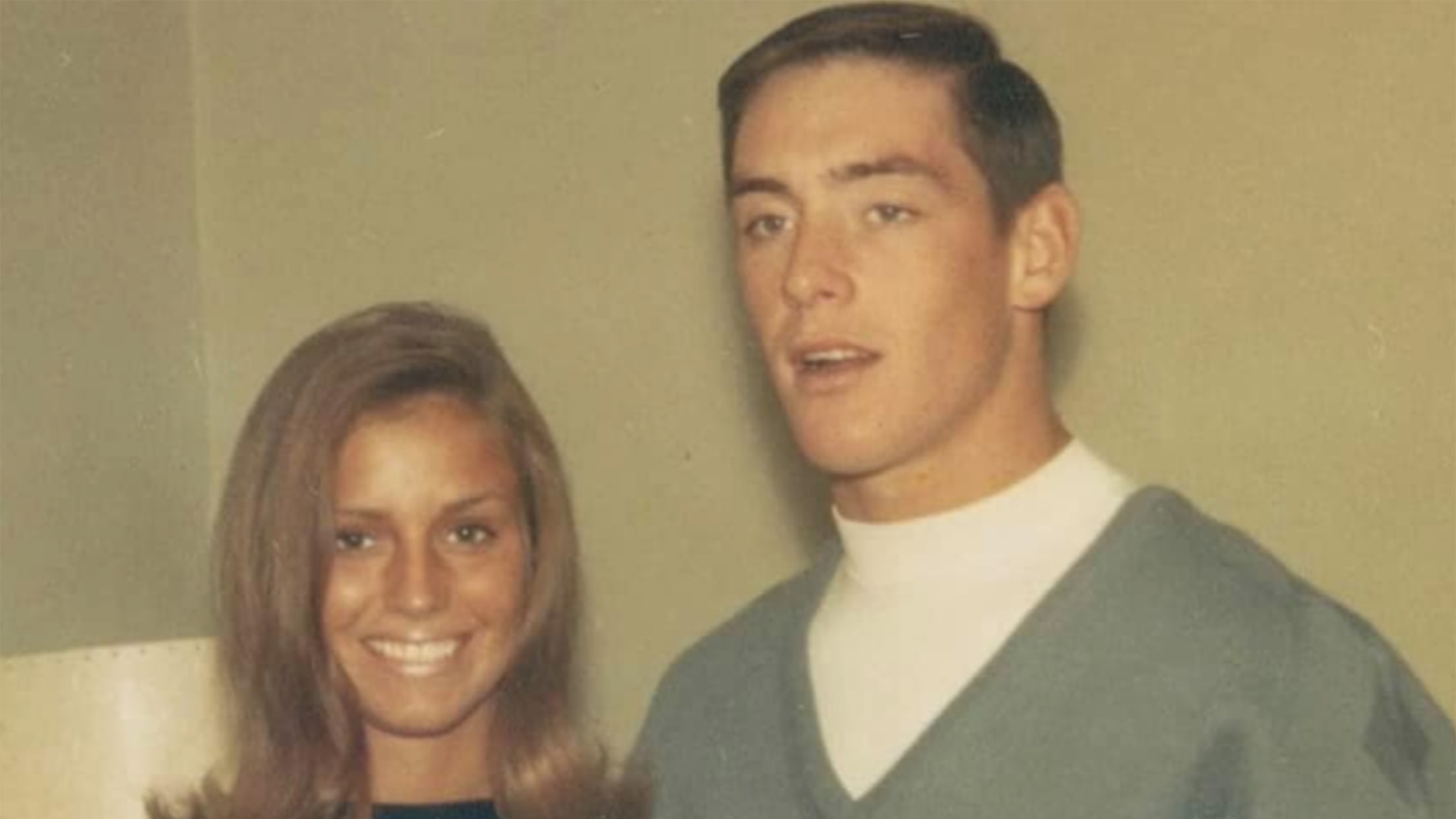

Oh, and have you heard the story about the time Ted and his wife, Maryanne Ellison Simmons, hitchhiked in Michigan with an aspiring rock star named Bob Seger?

Sources confirm: It’s true.

'BASEBALL WAS A CHESS GAME FOR HIM'

Simmons’ long, flowing hair earned him a memorable nickname: Simba. He planned to play baseball at the University of Michigan, until the St. Louis Cardinals selected him with the 10th overall pick in the 1967 Draft. He was 17 when he signed his first professional contract.

One year later, the Cardinals met his hometown Tigers in the World Series. The Cardinals arranged for Ted and Maryanne -- then his girlfriend, now his wife of 51 years -- to attend the games at Tiger Stadium. More than a half-century later, Simmons remembers the “horrible” internal conflict he felt. The Tigers were his boyhood team. Al Kaline was his favorite player. But now he was a professional. Baseball remained the game he loved -- but now it was his livelihood, too.

“I was sitting in the upper deck, watching the game with all of the Cardinals' front-office people,” Simmons recalled. “They knew I was from Detroit. I’d played that season in Modesto. At one point, Al Kaline got a big base hit to put the Tigers ahead. I did everything I could to prevent myself from cheering along with the rest of the crowd. I realized quickly enough where I was sitting and who was responsible for my tickets. I kept in my seat.”

Simmons spent 14 years in the Cardinals organization, absorbing the traditions and teachings of St. Louis baseball oracle George Kissell. Simmons made six All-Star appearances by the time he was dealt to Milwaukee after the 1980 season. He earned two more selections as a Brewer.

At first, Brewers players weren’t sure how to approach their new, serious-minded teammate. Simmons would read books in the clubhouse. He also enjoyed playing bridge, which evolved into a point of connection -- and instruction -- for his teammates.

He got the most out of his ability because of his mental approach. He out-thought everyone.

Former teammate Bill Schroeder

Simmons revealed the nuances of bridge to Schroeder, a fellow catcher nine years his junior. In cards, as in baseball, Simmons demanded accountability and honesty.

“He had such passion for everything he did,” Schroeder said. “When we were playing bridge, he’d jump on people if he thought they were trying to cheat. We’d be having a laidback card game in the clubhouse, but if someone wasn’t acting appropriately, Ted would be the first one to go over to you and say, ‘We can’t operate that way. That’s not how a big leaguer acts.’”

After games, the daily seminar met at Simmons’ locker. Attendance was required for younger catchers, including Schroeder and future MLB manager Ned Yost.

Questions were specific. Answers had to be, too.

In the fourth inning, you called a 2-1 changeup to Ripken. Why?

“Baseball was a chess game for him,” Schroeder said. “One pitch set up another, within the at-bat or later in the game. I got a sense for that through Ted.”

So substantive were those conversations, so enduring the lessons, that Yost hired Simmons as his bench coach in Milwaukee for the 2008 season. And when Yost won back-to-back pennants with the Royals in 2014 and ’15, he publicly cited Simmons’ influence on his managerial approach.

By the time Yost won the World Series, Simmons was well into his decades-long MLB front office and coaching career. He was general manager of the Pirates in 1992 and '93, before resigning from the position for health reasons after suffering a heart attack and undergoing an angioplasty. Simmons worked as an executive and scout for the Cardinals, Indians, Padres, Mariners and Braves.

'GET THE TYING RUN UP!'

Simmons also spent the 2009 and '10 seasons as the bench coach in San Diego, where he mentored catcher Nick Hundley during a crucial period early in his career. Hundley remembers how Simmons helped him to see the game holistically, in the context of a roadmap to 27 outs.

One example: It’s the eighth inning. The Padres are winning by two. The other team’s star -- Buster Posey, let’s say -- is the eighth hitter due up. With six outs to get, every pitch must be called with the goal of not allowing Posey to bat as the tying run.

“Even though that’s not something that would happen until the ninth inning, any 2-0 pitch in the eighth needs to be a strike,” Hundley explained in an interview earlier this year. “If you give up a base hit or a double, you can live with that. But he has to earn it. Otherwise, if you walk that guy, you’re one step closer to facing [Posey] as the tying run.”

Here’s another Simmons story -- about decorum, more so than strategy: Rick Renteria, then a Padres coach, was acting manager for a split-squad game in Mesa, Ariz., during Spring Training in 2010. Hundley had a 3-0 count against Cubs starter Carlos Silva. Renteria gave him the take sign. Hundley saw it, but the urgency to prepare for the season compelled him to swing away. He rocketed an RBI triple off the wall.

Simmons was furious.

It didn’t matter that the result was favorable. Hundley had disregarded a sign. Simmons asked Hundley if he would have swung away had the sign come from Padres manager Bud Black, instead of a coach. Hundley said he didn’t know. And that was the point.

Simmons didn’t speak with Hundley for two days.

“He held me accountable for it,” Hundley said. “I remember that to this day. That’s the kind of impact he has on people. He makes sure you do things the right way. You knew he was coming from a place of love, because he would do anything to help our team.

“One of the biggest things he did for us in 2010 was he would always build people up, no matter what the score was. We’d be down in a game, and he’d go up and down the bench, saying, ‘Just get the tying run up!’ And if it happened, when that batter was on deck, he would be so fired up. He’d yell, ‘That’s him! Right there!’ Even if we lost, he’d tell us afterward, ‘Hey, we got that guy up. We got the guy we wanted to the plate.’ It was such unbelievable perspective. He showed me how someone can really impact a game without playing in it.”

He makes sure you do things the right way. You knew he was coming from a place of love, because he would do anything to help our team. ... He showed me how someone can really impact a game without playing in it.

Nick Hundley

Simmons could be described as an adherent to baseball analytics -- before the field existed. He once noted that the average for pinch-hitters is substantially lower than that of Major League hitters overall. From a pitching standpoint, he said, the goal should be to turn every batter into a “pinch-hitter.”

How could a team accomplish that? Well, by ensuring no pitcher faces the same hitter twice. Once through the lineup, per pitcher, at the most. If that reminds you of the Rays’ or Brewers’ savvy approach to recent postseasons, it should. And Simmons contemplated the proposal during his playing career, which ended in 1988.

Fortunately, Simmons kept a record of his baseball experiences and reflections -- an unpublished journal that hasn’t been seen by the public and probably never will. According to legend, the magnum opus has philosophical paragraphs and diagrams of where every defensive player should be on a relay throw. Only a few copies exist. Simmons has the original, of course. Pete Vuckovich, his close friend and former teammate, has one edition.

“It might be 500 pages,” Vuckovich said earlier this year. “He put it into thick notebooks. Three-ring binders. There are probably two or three of them. He’s got everything in there: how to handle a bullpen, the things you need to do if you’re starting up an organization, what you look for in a starting pitcher.

“It might be boring to some people, but in terms of pure, old-school baseball, it’s very on the money.”

'A LIFE APART FROM BASEBALL'

Simmons did something else that is acknowledged as crucial now but wasn’t discussed as often when he played: He sought balance in life. And he found it.

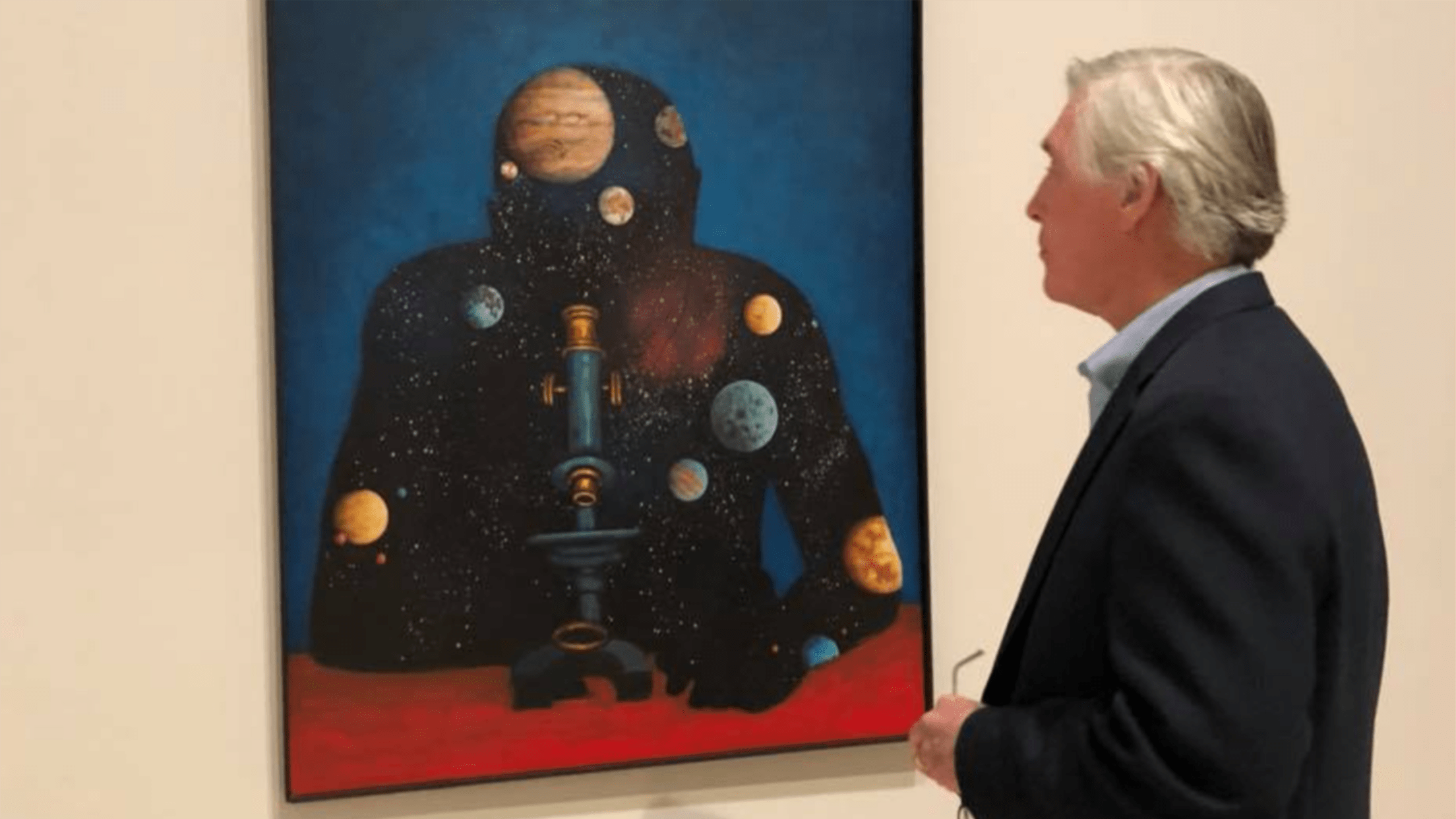

Maryanne is an accomplished artist with a bachelor’s of fine arts degree from the University of Michigan and master’s from Washington University in St. Louis. The couple has collected contemporary American art for decades. Earlier this year, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the St. Louis Art Museum acquired 833 works of art from the Simmons family -- a “partial gift, partial purchase,” for which “the museum paid just over $2.3 million, about half of the collection’s worth.”

Ted and Maryanne still make their home in the St. Louis area, where Maryanne owns Wildwood Press LLC, which specializes in custom papermaking and the printing and publishing of contemporary art. The couple’s sons have careers that have taken them around the world -- Jonathan to Australia and Matthew to San Francisco.

“You’ve got to be a human being first,” Simmons said. “That’s how I’ve lived my life, how I’ve kept everything compartmentalized and separated. By doing that, I was able to create a life apart from baseball. That’s very difficult for a Major League player to do -- not only for himself, but his [family] too.

“You have to carve out your own place and be the human being you want to be. Whether it’s going to the art museum, collecting furniture, contemporary art, works on paper -- all of these things are more of what there is in this thing called life, that everybody has a responsibility to do for themselves. ... I don’t believe anybody is entitled to anything. Everybody has an obligation to earn it.”

Ted Simmons earned it. He is a Hall of Famer.

The Modern Baseball Era Committee took a while to acknowledge that reality, but the length of their review has no bearing on the righteousness of the result.

Besides, they’ve elected a man who sees virtue, and perhaps a little art, in taking time to think it all through.