The remarkable story of Robin Yount’s brother Larry

My name is Larry Yount

And my story doesn’t rise

Like a ripple on the tide

Late at night I think what might have been

What might have been

The first time Larry Yount heard the song supposedly based on his life, his wife said, he shed some tears. It didn’t matter that the artist took some creative liberties and jumped to the kind of conclusions that probably anyone would have. The song tells the story of a young pitcher getting his first shot at the Major Leagues, getting injured while he warmed up on a big league mound and then never reaching the Majors again.

[This story was originally published in September 2021.]

The song tells the story of the regret and heartache that followed Yount throughout his life. He couldn’t go a minute without thinking about what could have been. Maybe he could have been an All-Star. Maybe he would have been a washout. Who knows? Maybe he could have been a Hall of Famer like his brother, Robin.

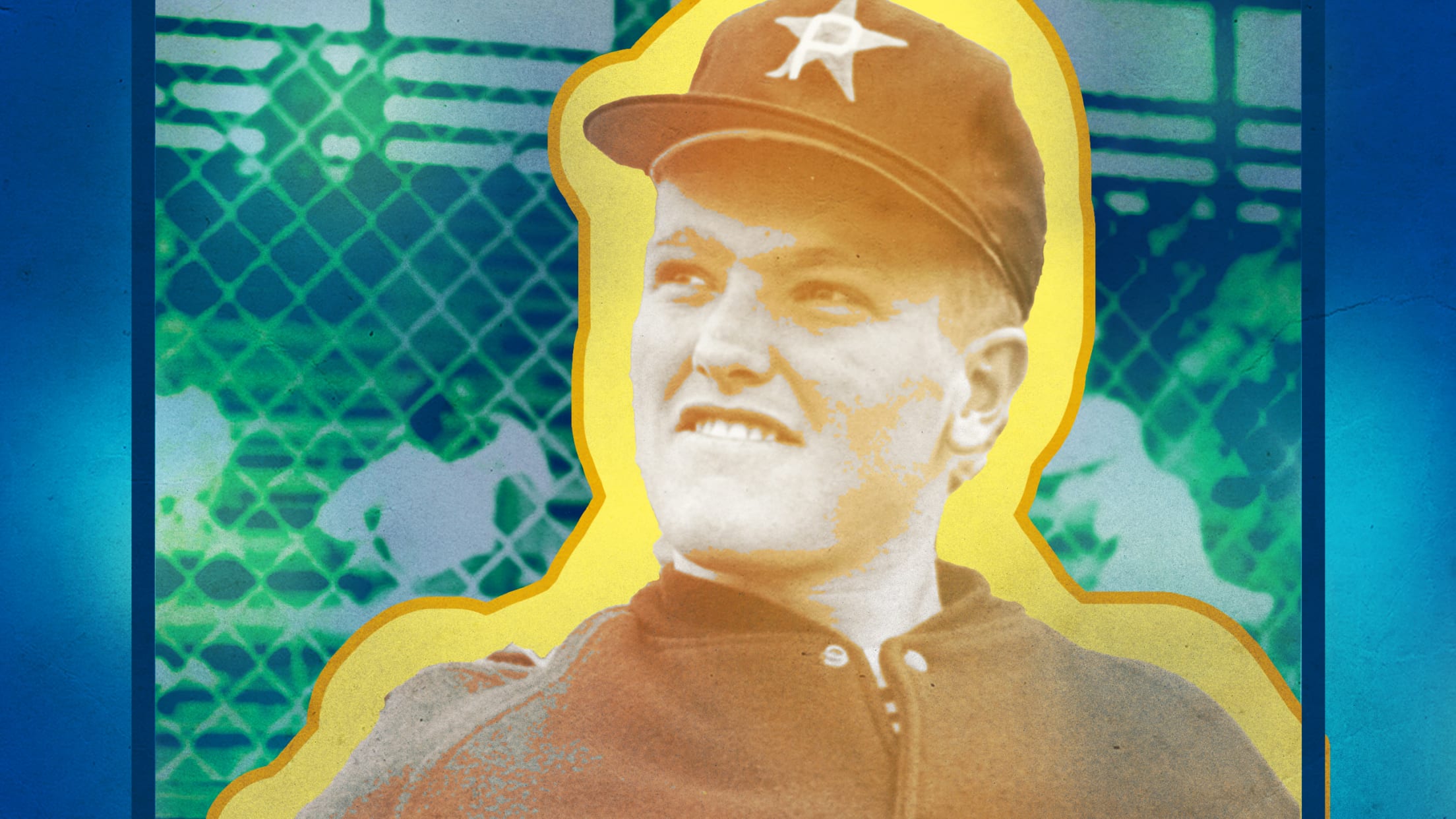

Sure, some of the what-ifs crossed his mind, but they didn’t stay long. If you know anything about Larry Yount, you know he lives life without regrets.

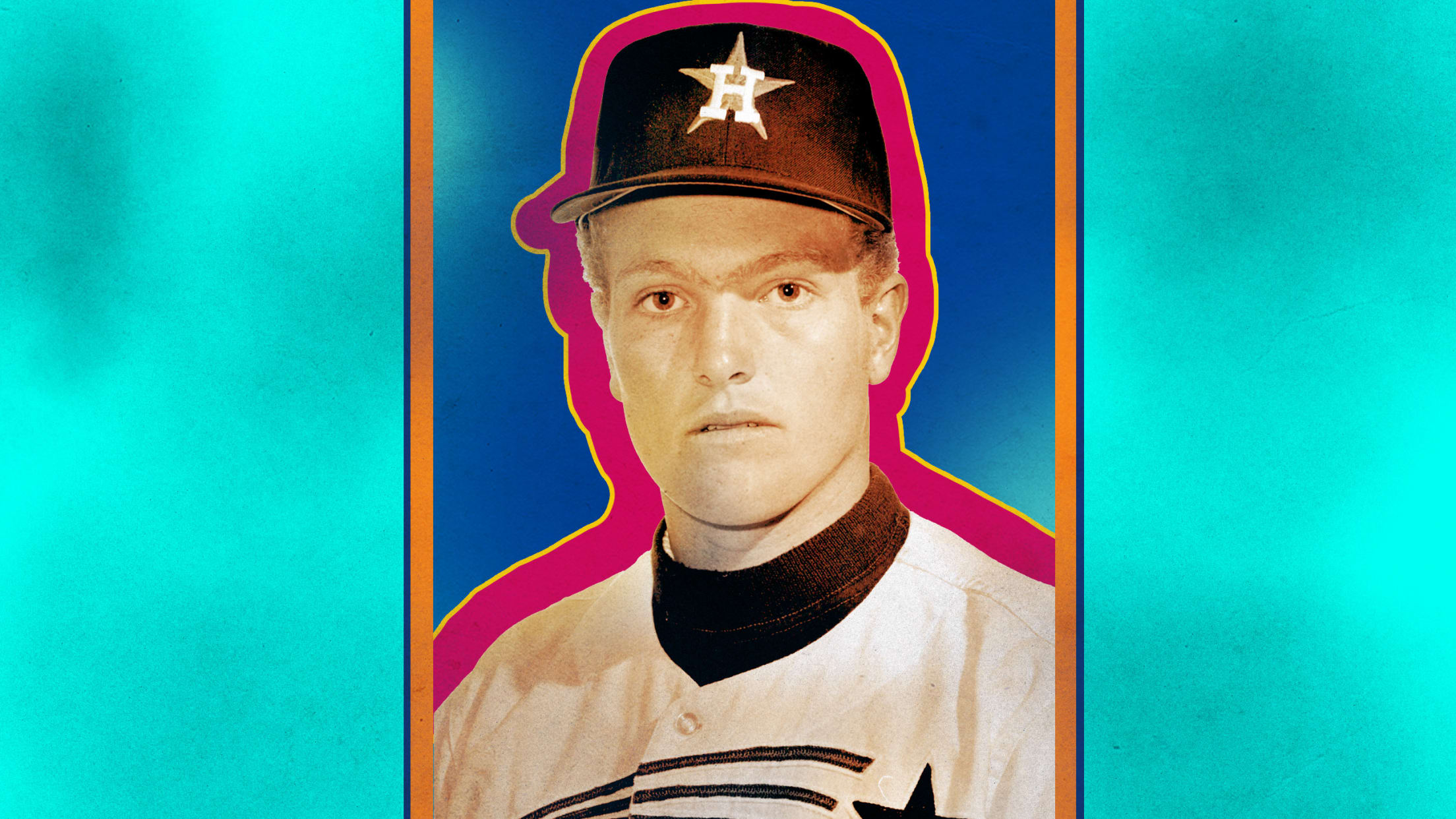

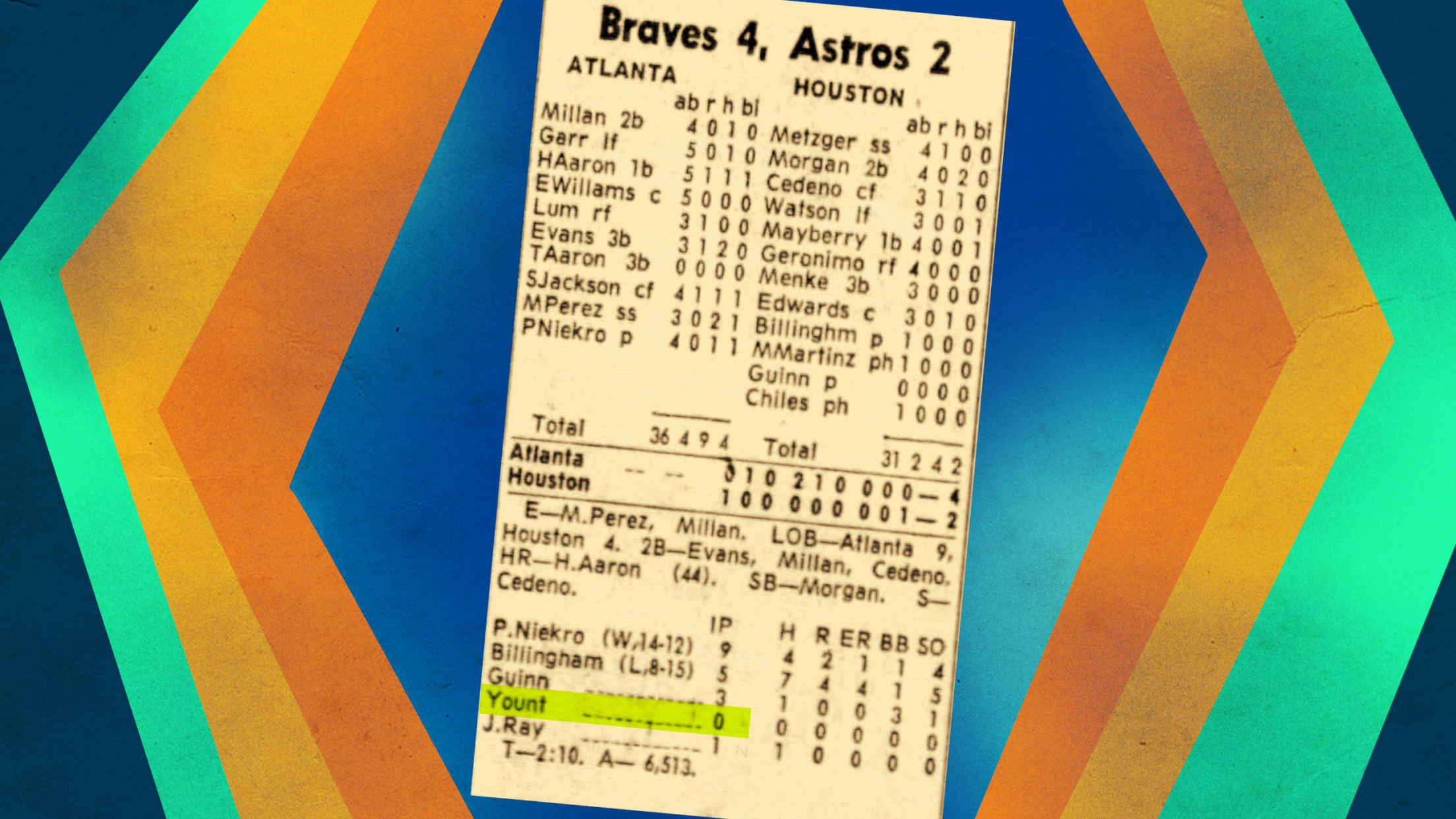

Larry Yount was 21 when he heard Astrodome public-address announcer J. Fred Duckett boom his name over the stadium loudspeakers. His name was written on the lineup card. It was official. He was a big leaguer. It was Sept. 15, 1971, and only 6,513 fans were on hand to watch the Astros meet the Atlanta Braves, a pair of scuffling clubs lingering around .500. It was such a nondescript day that nearly five decades later, Yount doesn’t remember where the game took place.

“I think it was in Atlanta,” he said.

Yount’s inability to recall specifics of the night, about his one official game in the Major Leagues, speaks to what the moment means to him now and how it certainly doesn’t define him. He knows he was warming up when he felt some pain in his arm. He summoned a trainer to the mound, then walked off the field. His teammates didn’t think much of it.

Neither did he. He figured his real MLB debut would come soon. It never did.

Larry Yount would never set foot on a Major League mound again.

********************

Prior to his big league moment, Larry had opened the 1971 season in Oklahoma City’s rotation and had a solid, though unspectacular season. He went 5-8 with a 5.45 ERA in 22 starts and was called up to the Majors when rosters expanded in September. Before he could join the big league team, however, he had to fulfill a two-week military obligation. He didn’t throw a ball during that stretch. It may have cost him a long big league career.

I decided to pull myself out of the game, and that was that. Never in my wildest dreams did I think that would be the end of my career.

Larry Yount

Yount, wearing No. 31, was in the bullpen when he was told to start warming up. He was going to pitch the ninth inning with the Astros trailing, 4-1.

“I remember going down and warming up, and as I was warming up, my elbow was pretty sore because I missed some days because of the military,” Yount says. “I [hoped] the adrenaline would kick in and it wouldn’t feel like my elbow was falling off. They called me in, and I decided to go out there and see what happens. After I threw a couple of pitches, I realized, ‘This isn’t going well.’

Though only 21, Yount was wise beyond his years. His arm didn’t feel right, and he decided not to push it.

“I decided to pull myself out of the game, and that was that,” he said. “Never in my wildest dreams did I think that would be the end of my career.”

The older of two brothers

And the first to break from home

Lawrence “Larry” King Yount was actually the middle of three brothers. He was born on Feb. 15, 1950, in Hermann Hospital in Houston, only a few miles from the Astrodome, to Phil and Marion Yount. Phil had a degree in chemical engineering and was a rocket scientist -- the head of quality control for the Apollo and Gemini space missions in the 1960s. They moved to Indiana, where Robin was born in 1955, then to Woodland Hills in the San Fernando Valley in 1956, when Phil took a job with Rocketdyne as an aerospace engineer.

Sports were everywhere in the Yount household. So was competition. The boys spent much of their free time outside in a huge backyard, playing football and baseball. They played baseball in the street with broken bats and plastic golf balls. Jim, the oldest brother and the light-hearted one, played football and baseball and later became a geologist and earned a PhD in oceanography.

Before anyone knew about Robin Yount, they knew about Larry. When Larry was 13, he was on a Pony League All-Star team that reached the 1963 World Series, a team that included future big league catcher Rick Dempsey.

As a junior at Taft High School, Larry was only about 5-foot-6, but he already had a good breaking ball. He grew about six inches and gained about 50 pounds the summer before his senior year and started to throw harder. Scouts started to take notice of the hard-throwing right-hander with the mean hook and strawberry blonde hair.

“He started as a small pitcher who relied on a curveball, and he had a really, really good overhand curveball,” said Bill Greif, a friend, teammate and one-time roommate. “But the funny thing is, as he got into high school and pro ball, he got to be big and strong and threw hard, too. It was a very good combination of a guy that grew up thinking he had to hit the corners and be smart and a guy that needed growing into a body that let him have good stuff.”

The Astros drafted Yount out of high school in the fifth round in 1968. Robin was only 12 at the time, and still five years away from being a first-round Draft pick -- No. 3 overall, one spot ahead of fellow Hall of Famer Dave Winfield -- by the Milwaukee Brewers. Larry, 18, wanted his little brother to succeed and bought him a pitching machine to put in the backyard.

“The old Iron Mike -- the one-armed bandit,” Robin says. “It was before they had real machines. And we built a batting cage out of chicken wire. Nets and all that were too expensive. My dad and I could put up six poles and string wire around it, but Larry bought me the pitching machine so I could go out there and hit baseballs in a chicken-wire fence. It developed a lot of holes over the amount of time I hit. A lot of balls would go right through and land two houses over sometimes.”

The Astros sent Larry to the Carolina League after drafting him. He was there only eight games before he was promoted to Triple-A Oklahoma City. In 1969, in his first full season of pro ball, Yount went 6-4 with a 2.25 ERA and was invited to big league camp in 1970, but the club sent him back to the Carolina League when the season started. He went 12-8 with a 2.84 ERA and was seen as part of an up-and-coming wave of pitching prospects.

“He was reading books about pitching, he was reading books about self-hypnosis, going out late in the day and running extra laps,” says former Astros pitcher Larry Dierker, who was an All-Star in 1971 and who also attended Taft, though a few years ahead of Yount. “He was just more consumed with making it than any other player I’ve been around.”

After years down in the Minors

Called up to the Astrodome

Houston, I was warming in the 'pen

Skipper said it’s time to come in

The day after the Astros beat the Braves on Sept. 15, 1971, the local papers barely made a mention of Larry Yount. His parents weren’t interviewed in the stands like they would have been today. In fact, they weren’t even there. The biggest news coming out of the game was Hank Aaron’s 636th career homer, which he hit in the fifth inning off Jack Billingham. Hall of Fame knuckleballer Phil Niekro threw a complete game for Atlanta, holding Houston to two hits.

Fast-forward to the following season. The 1972 Astros had a terrific starting pitching staff. Don Wilson posted a 2.68 ERA and had 13 complete games, and Dierker won 15 games, 12 of them complete. Dave Roberts went 12-7 with a 4.50 ERA. Yount, along with Greif and James Rodney Richard -- the hard-throwing Louisiana kid better known as J.R. -- found himself battling with Scipio Spinks and Tom Griffin for a spot on the big league club.

“I saw some articles that said I had a really good spring,” Larry said. “I thought I had a shot at making the club, and I probably did. I ended up being the last guy cut.”

Larry remembers giving up a homer late in the spring to Willie Davis of the Dodgers, a homer he thinks may have sealed his fate. The reality is that Spinks and Griffin were out of options -- meaning the Astros risked losing them for nothing if they tried to send them down -- so Yount was headed back to the Minor Leagues.

“Larry was just a real good guy, a great pitcher,” Spinks said. “He had just enough stuff to get there. With all the arms we had in the system, it was tough to stay in the big leagues. You have Larry Dierker at 18 years old pitching in the big leagues. It was tough.”

I took my warmup tosses

And I felt something snap

They pulled me out and they sat me down and

That was that

I never made it to the bigs again

That’s where the story ought to end

Yount won his first three decisions for Oklahoma City before things went awry.

“I don’t know what happened, but all of a sudden, I couldn’t throw strikes anymore,” he says. “I always had pretty good control, and then I ended up having a pretty bad year. I never could quite get it back again.”

Yount went 5-14 with a 5.15 ERA at Oklahoma City that year and searched for answers. He had a big upper body and shoulders, so tinkering with mechanics meant some wholesale changes. Every once in a while, he would overthrow, and the ball would sail toward the first-base dugout. Perhaps he listened to too many people. Perhaps he had lost his confidence.

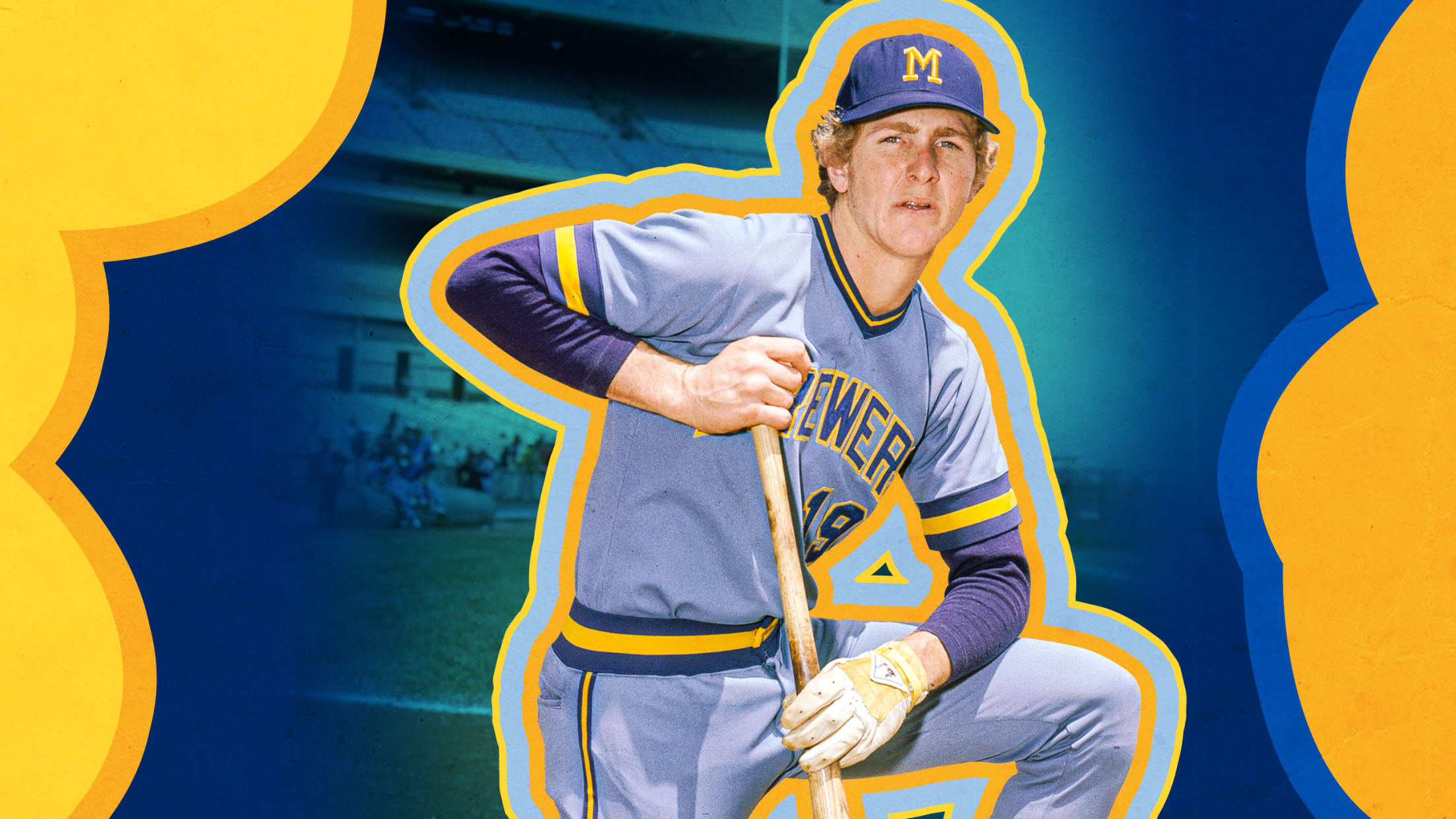

In 1974, Houston dealt Larry to Milwaukee, where he was reunited with Robin, who made the Brewers’ Opening Day roster at 18 years old and never looked back.

Says Robin: “My brother was basically a huge influence in getting me to where I was now, and all of a sudden, I’m in the big leagues and he’s in the Minor Leagues. It felt odd.”

After posting a 4.82 ERA in 26 combined starts at Class A and Double-A in 1975, Larry decided to retire at the age of 25. In 171 career games in the Minor Leagues, he went 45-71 with a 4.45 ERA. But in his one shot in the Majors, he didn’t even face a batter.

“It’s hard to feel as a big leaguer when you don’t really get in and play,” he says.

The reason you might know my name

Is because of my brother’s fame

Three years past my one day in the show

Robin got called up and he never let it go

Robin Yount made his Major League debut on April 5, 1974, against the Red Sox at County Stadium in Milwaukee, just 10 months after being drafted. His career couldn’t have been more different from his brother’s. Robin spent 20 years in the big leagues -- all with the Brewers -- and amassed 3,142 hits. He was the American League Most Valuable Player in 1982 and ’89, a three-time All-Star and a three-time Silver Slugger winner.

It was a stellar career that wound up getting him inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999. No one would have blamed Larry for feeling overwhelming envy or jealousy; Larry felt none of that.

“I could not be anything but proud,” Larry says. “Part of life is learning how to move on. And it all comes to an end at some point, no matter how good you are.”

Before he got to the big leagues, Robin spent the summer of 1972 in Oklahoma City with Larry and got the kind of experience other high school kids could only dream about. Robin served as the bat boy and learned as much as he could from the pros.

“I was getting a pretty fast education on what it was like to play at that level and I would go visit him and the guys he lived with when they were playing Triple-A during the summertime,” Robin said. “I usually got to spend a homestand.”

It wasn’t until around that time that Robin thought he could play professionally. He was more interested in riding motorcycles or playing golf. But Larry could see the baseball talent oozing from his brother, wanted to make sure he knew he had something special inside of him.

I’ll tell people to this day, ‘Don’t ever leave anything on the table. Go out there and give everything you’ve got.’ ... Well, that was something my brother told me in high school.

Robin Yount

“Larry told me, ‘You can do all this other stuff you want and whatever you choose to do is fine, but just promise yourself that every time you go on the baseball field …You’re only out there for three hours, but for those three hours, make sure you don’t leave anything behind,'” Robin remembers. "There’s something about the way he said it and told me that really made an impact on me. It was a pretty simple thing to say. I heard it, I guess. I basically played my whole professional career that way.

“I’ll tell people to this day, ‘Don’t ever leave anything on the table. Go out there and give everything you’ve got.’ People have made comments to me about the way I played. Those are the kind of things that mean as much to me as anything. People will say, ‘Yeah, we love the way you played because you gave it all you got all the time.’ Well, that was something my brother told me in high school. I held to that my whole career.”

In the 1980s, while Larry was building his post baseball life in Arizona, Robin was turning into a star player. It was Larry who negotiated directly with then-Brewers owner and future Commissioner Bud Selig for Robin’s first contract.

In his Hall of Fame speech, Robin told the crowd what Larry meant to him:

“My brother, Larry, he taught me how hard work and dedication to the game was the only way to make it. He’s taken care of all my business activities for me and my family for many years, and I thank him for that.”

After 20 years had passed

3,000 hits had been amassed

Robin hit the Hall of Fame and immortality

Some band wrote a song about me

In 2007, the night before R.E.M. was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, a musician named Steve Wynn attended a party in New York. Wynn knew R.E.M.’s lead guitarist, Peter Buck, pretty well, and was also acquainted with other members of the band, including Mike Mills and auxiliary member Scott McCaughey. Wynn and McCaughey sat at the bar of the Waldorf-Astoria talking -- no, debating -- baseball until 2 a.m., and as they were shooed out, they vowed to make a record that was about nothing but baseball.

The Baseball Project was born.

One year later, The Baseball Project was touring the Hall of Fame, and the members were asked by one of the curators if they knew the story of Larry Yount. The curator said, “Do you know what? This would make a great song.”

“We hear that all the time,” said Wynn.

The song broke my heart as I was writing it. I was fighting back tears as I was putting the chords together.

Steve Wynn

Since forming, the band has written dozens of songs about baseball and its characters and stories. One, “Buckner's Bolero,” is about the events leading up to Bill Buckner’s error in the 1986 World Series: I guess everything happens for some sort of reason/And there must be a tragic end to every long season/If even one man doesn't do one thing he does/We'd all know Bill Buckner for just what he was/A pretty tough out for the Dodgers, Red Sox and Cubs.

There are songs about Ted Williams, Fernando Valenzuela, Pete Rose, Ichiro and Curt Flood. These aren’t your average baseball fans -- Wynn even wrote a song about Harvey Haddix’s near perfect game.

But … Larry Yount?

“When I heard about Larry, I said, ‘That’s going to be an amazing song,’” Wynn said. “That’s everything we try to do, trying to find some universal human element, something that even if you’re not a baseball fan, you could relate to it in some way. The freakishness of the event, the brother rivalry that I invented -- which, as I found out, wasn’t entirely true. All those things made a great song.”

“Larry Yount” is the 15th track on The Baseball Project’s third album, “3rd,” which follows “Volume 1: Frozen Ropes and Dying Quails” and “Volume 2: High and Inside.” The song is three minutes and 42 seconds long -- probably about three times as long as Larry spent on a big league mound.

(Click here if video doesn't load.)

Wynn had never talked to Larry, but he was hellbent on writing a song about Yount’s brief and unique career.

“It’s almost like a jigsaw puzzle, sometimes, to get everything you want into the song, and that was the case with ‘Larry Yount,’” Wynn said. “How can I get across how unusual this was, how unprecedented an event this was for a guy to be in the Major League record book without even having thrown a single pitch? Adding Robin Yount to the equation, there was a lot to say in the song.”

Wynn mapped out what he wanted the song to say and admittedly jumped to some conclusions about his subject, as songwriters are wont to do. For Wynn, a gauge of a really good song is the feeling of emotional involvement. He could only imagine the heartbreak Larry felt at having his career cut short while watching Robin shine.

“The song broke my heart as I was writing it,” Wynn said. “I was fighting back tears as I was putting the chords together. I thought, ‘Hmm, this is working.’”

One man who wasn’t heartbroken was Larry Yount, who had long since put his career in a box at the back of his mind. Not only did he raise a successful family, he made a fortune in real estate in Arizona.

It was Yount’s youngest son, Cody, who heard the song first. He told his parents, who loved it, despite its creative inaccuracies. The song became a popular talking point among family members.

“There’s not many guys, I don’t think, that have not even an inning in the Major Leagues and have a song written about them,” Robin said. “So he must have done something right in baseball.”

The Younts learned to embrace both the song and the songwriter. Larry, wife Gail and Cody had dinner a couple of years ago with Wynn, who is on the Younts’ Christmas card list.

“I had no idea when I wrote the song of how successful Larry had become in real estate, that he had a pretty incredible career, that he had helped Robin’s career and given him guidance along the way,” Wynn said. “I think I did it almost like a heartbreaking, sad sack story. Turns out Larry did fine.”

Sometimes at the holidays

We’ll sit there with our kids

They walk past all the trophies

And ask ’bout the things he did

Gail and Larry Yount have been married 46 years, but they’ve known each other pretty much their entire lives, having grown up next door to each other. After the couple had been dating for four or five years, Larry was still trudging through the Minor Leagues, but Gail was 24 and ready to settle down.

Gail decided to drop a huge hint by buying her own engagement ring. It worked. During the 1976 Spring Training lockout, the couple eloped to Las Vegas.

The party that followed was the bigger story.

Gail’s uncle was in charge of entertainment at the Tropicana Las Vegas Hotel, and he arranged for a party that included showgirls from “Les Folies Bergere,” the revue that ran 50 years and was a Las Vegas institution.

“We got married and we called our parents, and my dad called my uncle and said, ‘Throw them a big party,’” Gail said. “So we had a big party with all the entertainment. Showgirls, the whole thing.”

Sometimes it tears me up inside

Though I can’t help but feel pride

I find I’m back in Houston once again

Thinking ’bout the things that might have been

Though Yount has been interviewed a million times about his baseball career, he doesn’t like talking about it too much. He still enjoys baseball, though, and his two sons played professionally. In fact, all four of Gail and Larry’s children were into athletics. The family was so busy and spread out from kids’ activities every night that family dinners were held in restaurants.

“To get all the kids different places at pretty much the same time and try get homework done and cook dinner, it became impossible,” Robyn, the oldest of the four, said. “It became this thing at our house. My parents would be like, ‘Hey, if we want to sit down to a family dinner, we’re going to go out to dinner,’ so every night we would go out to dinner when everybody was done with all their sports. … My mom would say, ‘Dinner’s ready, hop in the car.’”

He does not drive a fancy car. He does not dress in fancy clothes. The office where we work out of still looks the same as it did when it was built in 1981. He’s a man of few words, but when he does talk, you definitely respect what he says.

daughter Robyn Yount

Both parents were extremely encouraging and pushed education. Larry didn’t go to college, maybe regretfully so, but was determined to see his kids get solid educations.

“Something my parents were both very good at was encouraging us to pursue whatever our interests were,” son Austin said.

Uncle Robin, what’s it like?

Uncle Robin, tell us more

About the World Series games

And statistics and the scores

While Robin Yount was blossoming into one of the greatest players in Milwaukee Brewers history, Gail and Larry moved to Scottsdale, Ariz., where Larry -- who had gotten his real estate license while playing in the instructional league in Arizona -- started his own real estate business. He developed his first shopping center when he was just 28, and although he has had a lucrative career both buying and selling land, he remains humble.

“He’s very humble,” said Robyn. “He does not drive a fancy car. He does not dress in fancy clothes. The office where we work out of still looks the same as it did when it was built in 1981. He’s a man of few words, but when he does talk, you definitely respect what he says.”

Larry drives a small Lexus SUV, and according to brother Robin, “He probably bought it used, too. … Just the way he rolls. I think he likes to see how much money he can make and pass it on, because he’s definitely not going to spend it, I know that.”

Robyn has worked with her father for 16 years, and Cody joined the business a couple of years ago. That’s the extent of the company’s employees. It’s a barebones operation, but a lucrative one.

“Nothing fancy, for sure,” Robyn said. “If you sit in one of our chairs, it might break.”

When the real estate business took a tumble and property values plummeted in Phoenix during the savings-and-loans scandal in the 1980s, Yount took a supplementary job as the president of the Phoenix Firebirds -- the Triple-A team of the Giants in the days before the Arizona Diamondbacks. He did real estate during the day and ran the team at night.

“So all four of us, when we were really little, grew up going to the ballpark every night,” Robyn said. “He did that so we all would have an appreciation for baseball. We grew up at the ballpark.”

The real estate market eventually rallied, however, and Larry was back in business. Success is how you look at it, Larry said, but he admits he did overachieve in his post-baseball life.

“I told people I probably got 120 percent out of my business ability and about 80 percent out of my athletic ability,” he said.

My name is Larry Yount

And my story doesn’t rise

Like a ripple on the tide

Late at night I think what might have been

On the grounds of Gail and Larry’s home are a par-three golf course and a baseball infield, both meticulously manicured. There’s also a guest house, which is where Jeremy Bleich’s chapter of the Larry Yount story begins.

Bleich played baseball at Stanford with Austin and was a first-round pick of the Yankees in the 2008 MLB Draft. The two are close friends.

Jeremy’s career never quite panned out like he had hoped. Injuries and underperformance took its toll, and he bounced from the Yankees to the Pirates to the Phillies to the Dodgers. He signed with the D-backs in 2017, clinging to the hope of making it to the big leagues.

Scottsdale rent in the spring is outrageous, so Austin had an idea; Jeremy could stay in his parents’ guest house. And once Gail found out Jeremy needed a place to stay, she demanded he stay with them.

“They would call me every night and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to go to dinner. Come outside,’” Bleich said. “I got to know Larry more on a personal level at that point. We’d go out, and it was just me, Larry and Gail. For me, a lot of stuff I would talk to my dad about kind of started coming out during these dinners.”

That year, Bleich played for Team Israel in the World Baseball Classic in Korea. In three games, he struck out two batters in 2 1/3 innings. The reports on him were so good that he got in some big league games later in the spring for the D-backs. He learned a new slider. He thought he was in a good place.

“With a couple of days left in Spring Training, I got released, and it kind of caught me off guard a little bit,” he said. “It was the second time in my career I’ve been released, but with all the positive feedback I have been getting from the big league staff itself, it surprised me to get released from the Minor League side. It threw me off.”

On his way back to the Younts’ guest house, Bleich called Gail and let her know the news, saying he wasn’t going to need a place to stay anymore and that he was packing his bags. He thanked her for everything and told her to thank Larry, as well.

A dejected Bleich sat on the front porch of the main house.

“Larry pulls up and says, ‘Hey, come over here and sit down.’ Very matter of fact,” Bleich said. “He sits across from me. He says, ‘You’re going to be fine. You’ve got a great education, you’ve been through a lot with baseball, you’ve traveled internationally. ... I remember having this talk with Austin, but you can do whatever you want and you need to feel that way, and you should be confident about that.’”

Bleich kicked around the idea of retiring before signing with an independent league team in New Jersey while he lined up job interviews in New York City. Like Larry, he was fascinated by real estate. He would interview in the morning, hop on a train and then play baseball at night.

“Big deal, right?” Bleich said. “I go there for 10 days, and I get a call from the Dodgers. They want to bring me to Triple-A. I wasn’t sure what I was doing, but I was, ‘All right, I’ll be there.’”

Things came together for Bleich, who was throwing hard and throwing strikes. He signed with Oakland in ’18 and had another solid year in the Pacific Coast League. Then, after about 10 years in the Minor Leagues, Bleich was called up on July 13, 2018. Meet the A’s in San Francisco, he was told. That was ideal for Austin and his wife, Bess, who lived in the area, who went to AT&T Park to see Bleich’s debut. Austin asked Bleich to leave him an extra ticket, but didn’t say who it was for.

“I’m getting everyone tickets and basically spending my first game check on tickets,” Bleich said.

Bleich made his debut that night in relief, entering the game with the bases loaded in the seventh inning and the Giants ahead, 2-1. It was a mess. He gave up a two-run double to Steven Duggar and hit Brandon Belt with a pitch. And that was it. His debut was over seemingly before it started. He threw four pitches, and he didn’t record an out. The A’s lost, 7-1.

After the game, Bleich walked out of the clubhouse to meet his family and was stunned when he saw Larry standing off to the side. He had no idea Larry had made the trip from Arizona to see him.

“That was his way of not making a big deal out of it,” Bleich said. “This is my guess. I don’t know for sure. I would never ask him. He told Austin, ‘Hey, get me a ticket, don’t tell him I’m coming.’ He’s never in the spotlight, didn’t want attention for doing these things, didn’t want to make a deal, but, like, he showed up.”

Bleich retired from baseball following the 2019 season and pitched for Team Israel in the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo. He’s a Major League staff assistant with the Pirates and remains close with the Younts.

He appeared in only two big league games.

That’s one more than Larry Yount, whose moment in the bigs is now only a footnote to a life well lived.

“He’s happy with his life, and he should be,” Gail said. “He should be very proud of what he’s accomplished with everything -- as a father, a husband and businessman.”

My name is Larry Yount

My name is Larry Yount

My name is Larry Yount