Rickwood Field road trip -- Part III

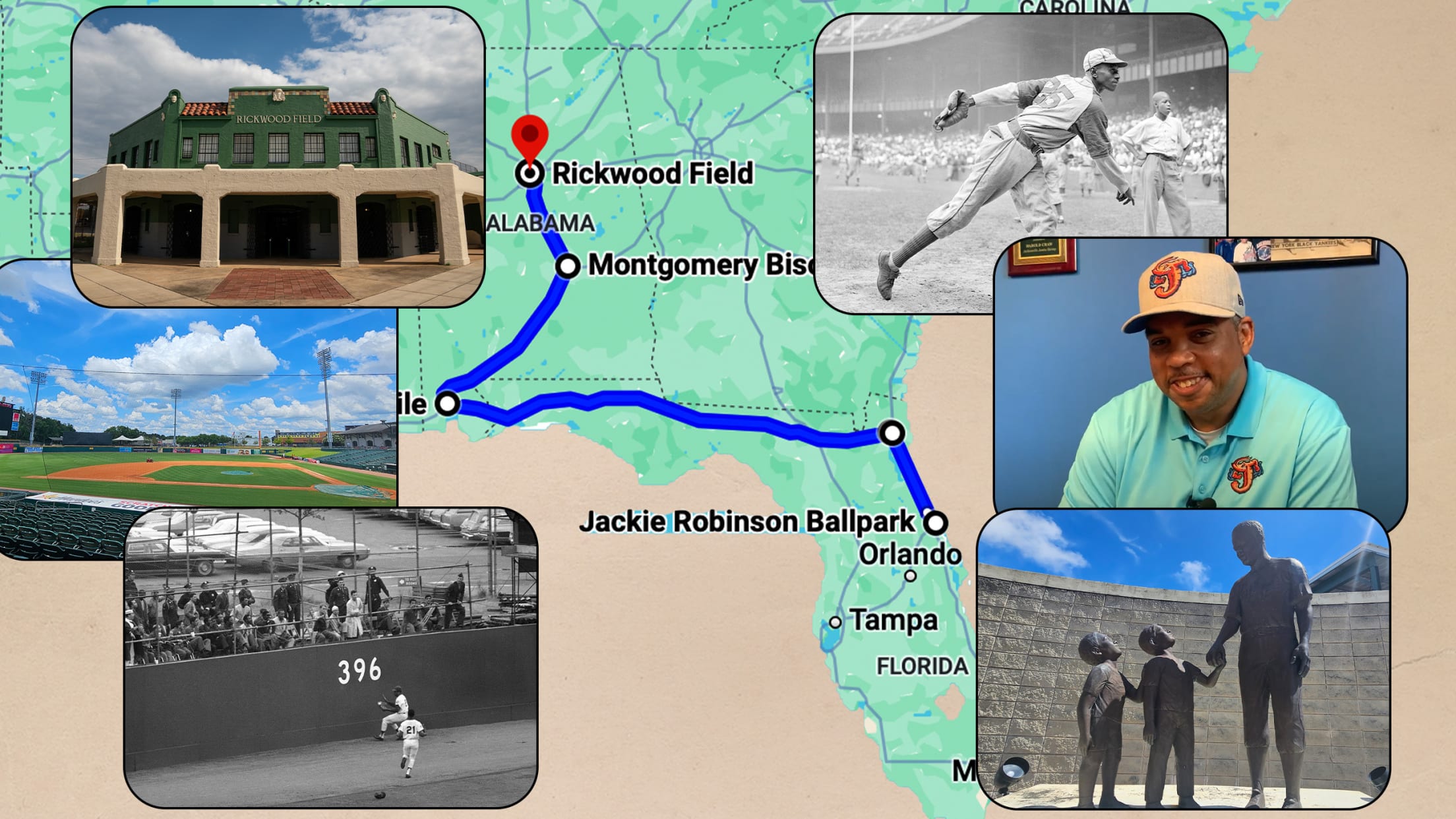

Birmingham’s Rickwood Field – the oldest professional baseball stadium in America, standing since 1910, and the former home of the Negro American League’s Birmingham Black Barons – hosted Minor League Baseball and Major League Baseball games this week, and on the way to the hallowed ground, MLB Pipeline took a road trip through Florida and Alabama in search of more stories that tell the history of Black baseball in the South. Part I of that trip, covering stops in Daytona Beach and Jacksonville, is available to read here. Part II, covering Mobile and Montgomery, is here.

BIRMINGHAM, NEGRO SOUTHERN LEAGUE MUSEUM

Opened in August 2015, the Negro Southern League Museum sits one block north of Double-A Birmingham’s home ballpark Regions Field, making baseball squarely a focus of the city’s Southside neighborhood.

The museum works as a joint effort by the Center for Negro League Baseball Research (headed by Dr. Layton Revel), which provides most of the artifacts on display, and the City of Birmingham. While the city isn’t in the official name itself, it might as well be with the way the entire experience tells the story of Birmingham baseball from the Industrial League of the 19th century through the Negro Southern League’s Birmingham Black Barons to modern times with local Black athletes like Bo Jackson and Ron “Papa Jack” Jackson.

“If I had to choose one location in the United States, it would be Birmingham, Alabama for the following reasons,” Revel said. “Number one, the Birmingham Black Barons played more Negro League baseball games than any other team that played in the Negro Leagues. Secondly, we have Rickwood Field here, of course. From 1910 to 1963, it was the home field to the Birmingham Black Barons, and it's still here. Third reason is we had the Birmingham Industrial League here. The Birmingham Industrial League was started in the early 1890s, and it sent more players to the Negro Leagues than any other organizations in the country.”

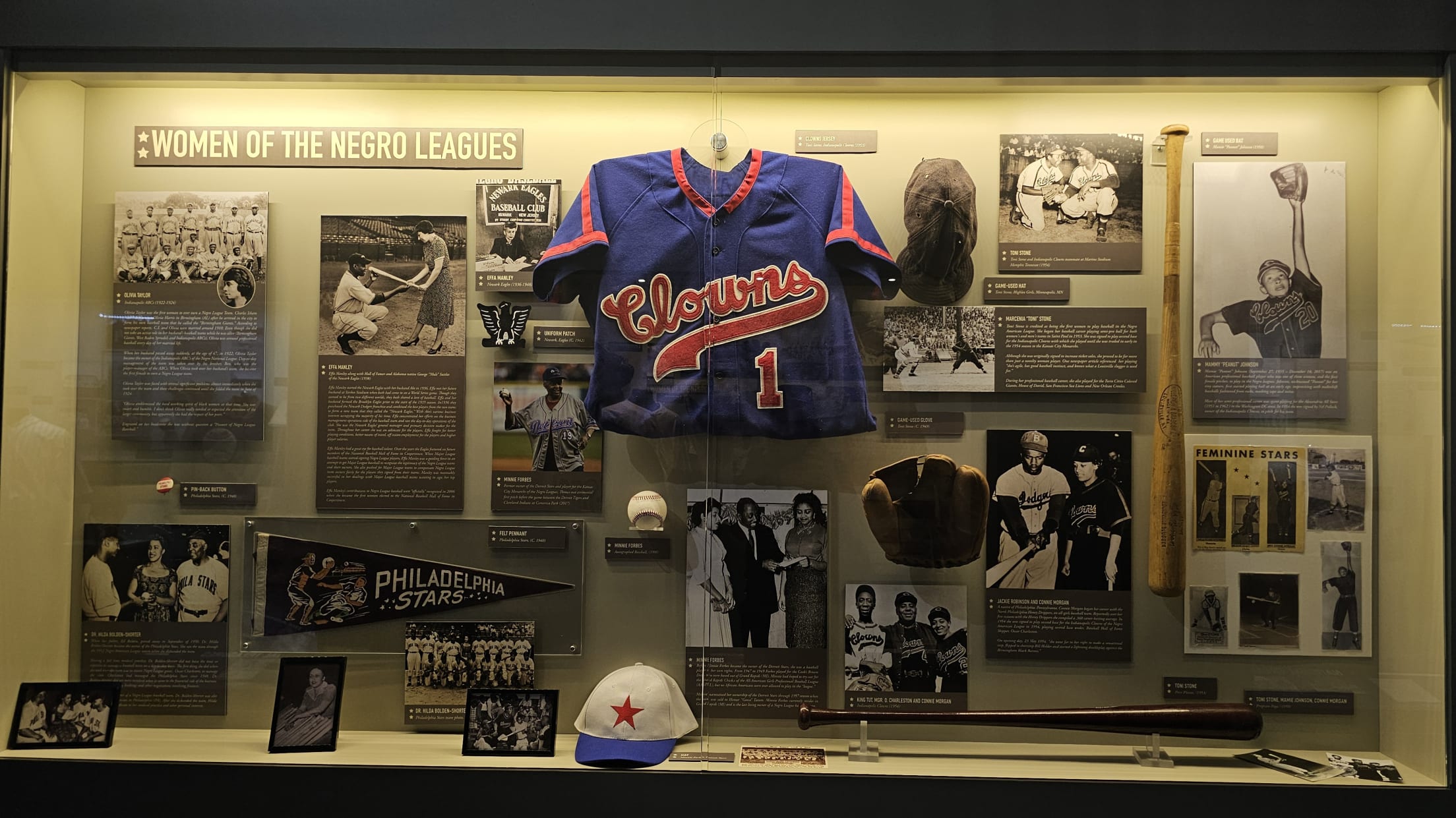

Visitors can stand inches away from the signatures of legends like Hank Aaron, Buck O’Neil and Jackie Robinson. They can gawk at a game-used uniform from Satchel Paige, and feet away from that, they can use a light-based pitching simulator that shows just how fast the right-hander threw his hurry-up ball, hesitation pitch, wobbly ball and midnight rider. An exhibit on women in the Negro Leagues houses a game-used hat, game-used glove and Indianapolis Clowns jersey from Toni Stone. Another highlights the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons – arguably the best in team history that made that year’s Negro League World Series.

There is one corner that will catch a lot of attention this week – the one devoted to Rickwood Field itself. There’s even a broadside advertising the stadium’s first matchup from Aug. 18, 1910 between the Birmingham Barons and Montgomery Climbers.

“It's just a great time to start looking back and try to reclaim some of this history and forge a new path,” said director Anthony C. Williams. “Because we can't really explain why there was a Negro League and a regular league. How do we tell that story to our kids? But it's the truth. So I think now is the time to look back and try to make sense of and to recognize these players who may have gotten left out and to really tell their stories.”

In truth, interest in the Negro Leagues is hitting a 21st-century high.

The “MLB: The Show” video game series has brought new, interactive attention to that period in the game’s history, allowing fans young and old to play as the legends they may have read about or seen in old pictures. Stone, for instance, took on a new level of fame when she was included alongside Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard and Aaron (whom she replaced on the Indianapolis Clowns in 1953) in “Storylines 2.” Kansas City’s Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has expanded to have a national presence, and its president Bob Kendrick served as players’ guide through history in this year’s edition of the game.

Between the Rickwood games and the growing popularity elsewhere, the National Southern League Museum is ready to take its place in the conversation at every level.

“As long as I’m here, my pursuit will be to get this information to as many as possible,” Williams said. “To invite youth organizations, schools, tours, whatever it may be – youth baseball organizations especially – to be able to know these stories. I think once people learn just how important baseball was to this region and how rich the history is, I think the youth will have a different idea of their area. … I think they’ll walk with their heads a little bit higher.”

Those raised heads might pick up one more detail, a quote from Ted Williams about one other local legend and former Black Baron.

“They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays."

BIRMINGHAM, RICKWOOD FIELD

Rickwood Field is a cathedral, a museum and a big, beautiful baseball diamond rolled into one.

Tuesday’s MiLB at Rickwood game between Birmingham and Montgomery – the first Minor League contest held at the historic park since 2019 – served as a table-setter for the big week to come. But make no bones about it, it was not simply a dress rehearsal for the MLB game between the Cardinals and Giants two days later.

Rather, it was Rickwood’s first opportunity to show off the improvements that made this whole week possible. A new playing surface that brought it up to MLB standards. A shorter backstop. Improved dugouts over the previous editions that, as Friends of Rickwood chairman and executive director Gerald Watkins, could “fit 12 people on a good day.” New outfield dimensions, most notably bringing in center field from 478 feet to 400. New foul poles. Different lighting.

For this week’s events alone, Major League Baseball installed a Fan Plaza, adorned with signs and graphics celebrating Negro League stars like Cool Papa Bell and Rube Foster.

But one thing that never needed replacing was the aura.

A popular picture spot for fans was in front of the green facade at the original main entrance into the park, throngs wanting to prove they stood on the same grounds as so many of the game’s greats. By one count, 181 Hall of Famers have appeared in games at Rickwood Field, whether it be as Minor Leaguers, Negro Leaguers, barnstormers, Major Leaguers making their way north from Spring Training, etc.

This was where, legend has it, Babe Ruth homered onto a train headed for Atlanta. It’s where Reggie Jackson may have gone even deeper (if we don’t account for locomotive travel). It’s where Fairfield, Alabama’s own Willie Mays suited up for the Birmingham Black Barons. In a statement earlier this week, the 24-time All-Star said, “The first big thing I ever put my mind to was to play at Rickwood Field.”

On Thursday – just before the MLB game – Jackson, speaking on FOX’s pregame show, reminded the audience that baseball in Birmingham doesn’t have as rosy a history as its Rickwood all-time roster would indicate. The first integrated team in Alabama history didn’t play in Rickwood until 1964. Three years later while playing for Birmingham A’s, Jackson was still being told he couldn’t eat in certain restaurants or stay at certain hotels because of the color of his skin.

By 1988, the Southern League club moved to the suburb in Hoover, and while Rickwood was falling into disrepair, production on the 1994 movie “Cobb”, which wanted to use the site for filming, injected new life into the ballpark. High-school and college games became regular affairs, and Minor League Baseball returned for one-off contests called the Rickwood Classic from 1996-2019.

But with the latest effort, locals have been hopeful that Rickwood’s latest revitalization can uplift the entire region.

“For the city of Birmingham, this is like a TV commercial or documentary about the city,” Watkins said. “Citizens past and present, we couldn’t afford to by the attention we’re getting. Not only are people going to be coming to Birmingham, they’re going to coming to grips with Rickwood Field and other sites as well. It’s going to say a lot and do a lot to show how this city changed from the image it had in the ‘60s.”

As for the game itself, it served as the opener in MLB’s Tribute to the Negro Leagues with Montgomery and Birmingham wearing Gray Sox and Black Barons uniforms, respectively. Birmingham natives and Negro League alumni Clinton Forge, Alphonse Holt, Joseph Marbury and Ferdinand Rutledge met with players from both sides and threw out ceremonial first pitches.

The Rays and White Sox prospects weren’t just reading about the history of the game’s oldest professional ballpark; they were direct participants.

“I had to take a couple laps around the field just to see the atmosphere,” said Montgomery center fielder Chandler Simpson, “feel the energy, just to be in the presence of all those greats that came before me.”

The moment was especially not lost on Tampa Bay’s No. 10 prospect, the son of two Atlanta-area educators who had told him about the Negro Leagues beginning when he was around eight years old. His father, Dr. Ralph Simpson, traveled the two hours from Atlanta to Birmingham to witness his son leading off for Montgomery, thus becoming the first official batter in Rickwood’s new-look state.

“We’re all just here to support it,” said the elder Simpson. “He’s embracing what all of this means but knows and understands that he has to go out and produce. A lot of kids, not just African-Americans, are going to follow him because some of those same kids have aspirations and may have a similar-type game. They want to look at him and know that their game will translate.”

Simpson’s game, referenced by his father, is one of a slap-and-dash -- get on base with dinks and dunks into the outfield and keep the pressure on the defense with blazing speed. True to form, the outfielder, who spent two years in Birmingham at UAB before transferring to Georgia Tech, singled to right on the game’s second pitch and stole second and third within the next at-bat. He’d finish the night 3-for-4 with three stolen bases before being lifted for a minor calf injury, pushing his average to .375 and his SB total to 51 – both tops in the full-season Minors.

With Mays being talked about all week as the game’s quintessential five-tool player, Simpson showing off his elite hitting and running skills was no mistake.

“I was sleeping on that last night, and I was dreaming about that and visualizing that today,” he said. “When I got that first hit, I knew I was going to take off no matter what, and I was going to take third.”

Many remained locked into the old-school feel of the Rickwood opener for much of the evening, but murmurs began to spread around the later innings. Mays – the all-time great who roamed this very outfield as a teenager nearly seven decades earlier – had died at 93. An announcement on the newly built electronic scoreboard in right-center confirmed it to those who hadn’t heard.

But instead of giving a Giant of the pastime a moment of silence, the crowd organically turned to what he had more typically heard during his Rickwood days instead – back when folks arrived at the ballpark straight from church in their Sunday best to catch an afternoon game, when Mays and his fellow ’48 Black Barons earned bigger crowds than their white counterparts. They clapped. They cheered. They tipped their hats toward the field.

Willie’s field.

“He was definitely here in spirit throughout the whole game,” Simpson said.

“It definitely hits you a little bit,” Birmingham manager Sergio Santos said. “I think it gives you feedback on what an honor it is not only to wear the jersey but to participate in a game like today. Obviously, baseball is big, but life and death is something bigger. Willie Mays, what a legacy we’re all trying to fulfill and play the game the way he played.”

And so the teams played on, Montgomery holding off a late Birmingham charge to win 6-5. A “Barnstorm Birmingham” celebrity softball game on Wednesday and the Cardinals’ own 6-5 victory over the Giants on Thursday kept the Rickwood festivities going, but our trip ended with the Tuesday opener.

A three-day journey through Florida and Alabama – with stops relating to Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, the Major Leagues, the Minor Leagues, the Negro Leagues, the history of the game, the present of the game, the future of the game – came to an end. It was always culminating in the longtime home of baseball in Birmingham, but Magic City made sure that diamond sparkled for all to see.

“This whole week,” Watkins said, “has made Rickwood Field the center of the baseball universe.”