Rickwood Field road trip -- Part I

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – When the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee – containing baseball historians and journalists as well as former executives and players – released its findings last month that led to the incorporation of Negro Leagues stats into the Major League database, it made sure to highlight how fans should look at the history books.

“By realizing that statistics are shorthand for stories, that history is not product but process, and that the reasons for the very existence of the Negro Leagues are worthy of our study.”

But the history of baseball is not told by statistics alone. It is told by ballparks. It is told by bats and balls and gloves and cleats and hats and uniforms. First and foremost, it is told by people.

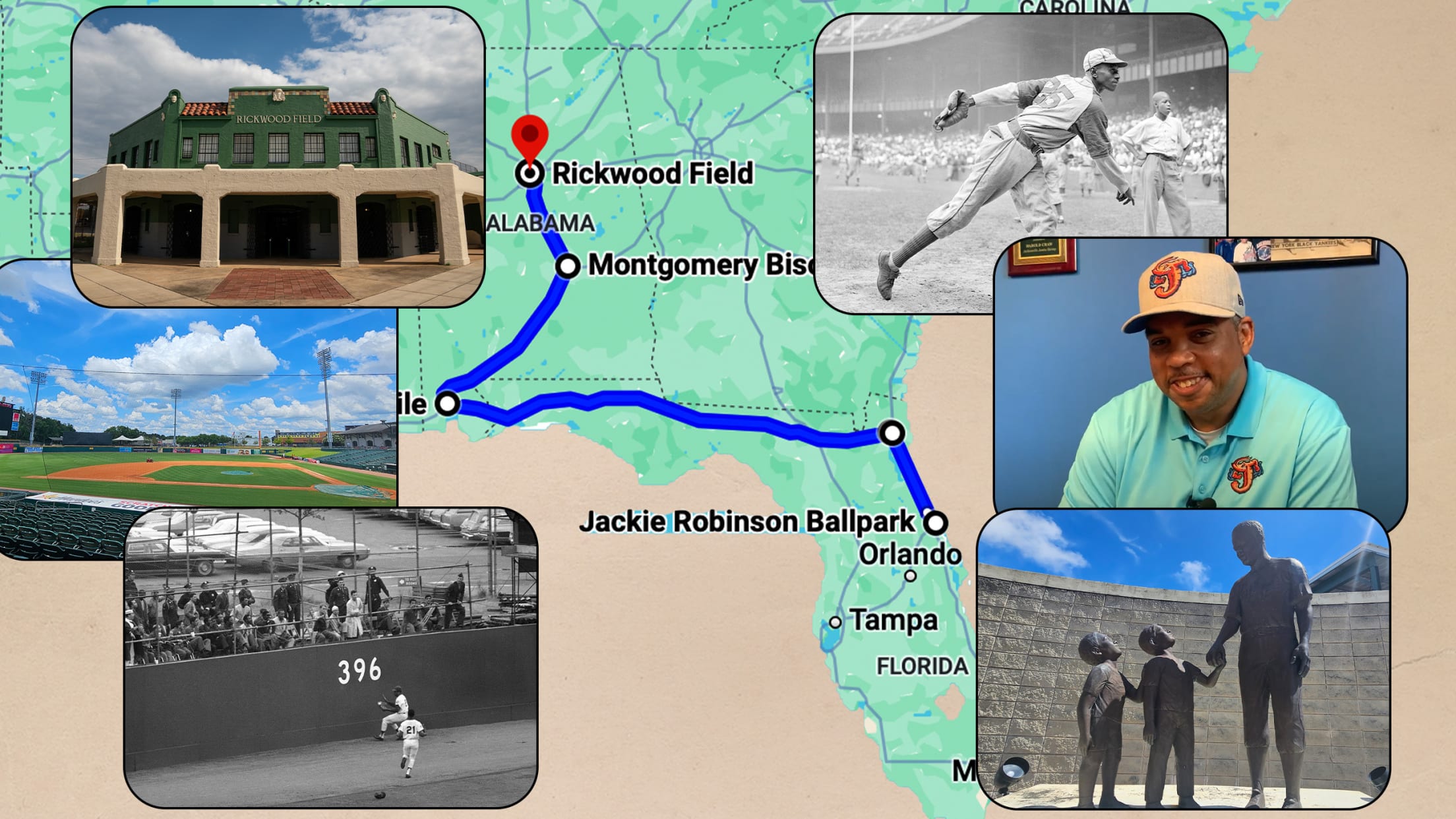

Birmingham’s Rickwood Field – the oldest professional baseball stadium in America, standing since 1910, and the former home of the Negro American League’s Birmingham Black Barons – is hosting Minor League Baseball and Major League Baseball games this week, and on the way to the hallowed ground, MLB Pipeline took a road trip through Florida and Alabama in search of more stories that tell the history of Black baseball in the South. Part II of the trip, covering Mobile and Montgomery, is available to read here. Part III, covering multiple stops in Birmingham, is here.

DAYTONA BEACH

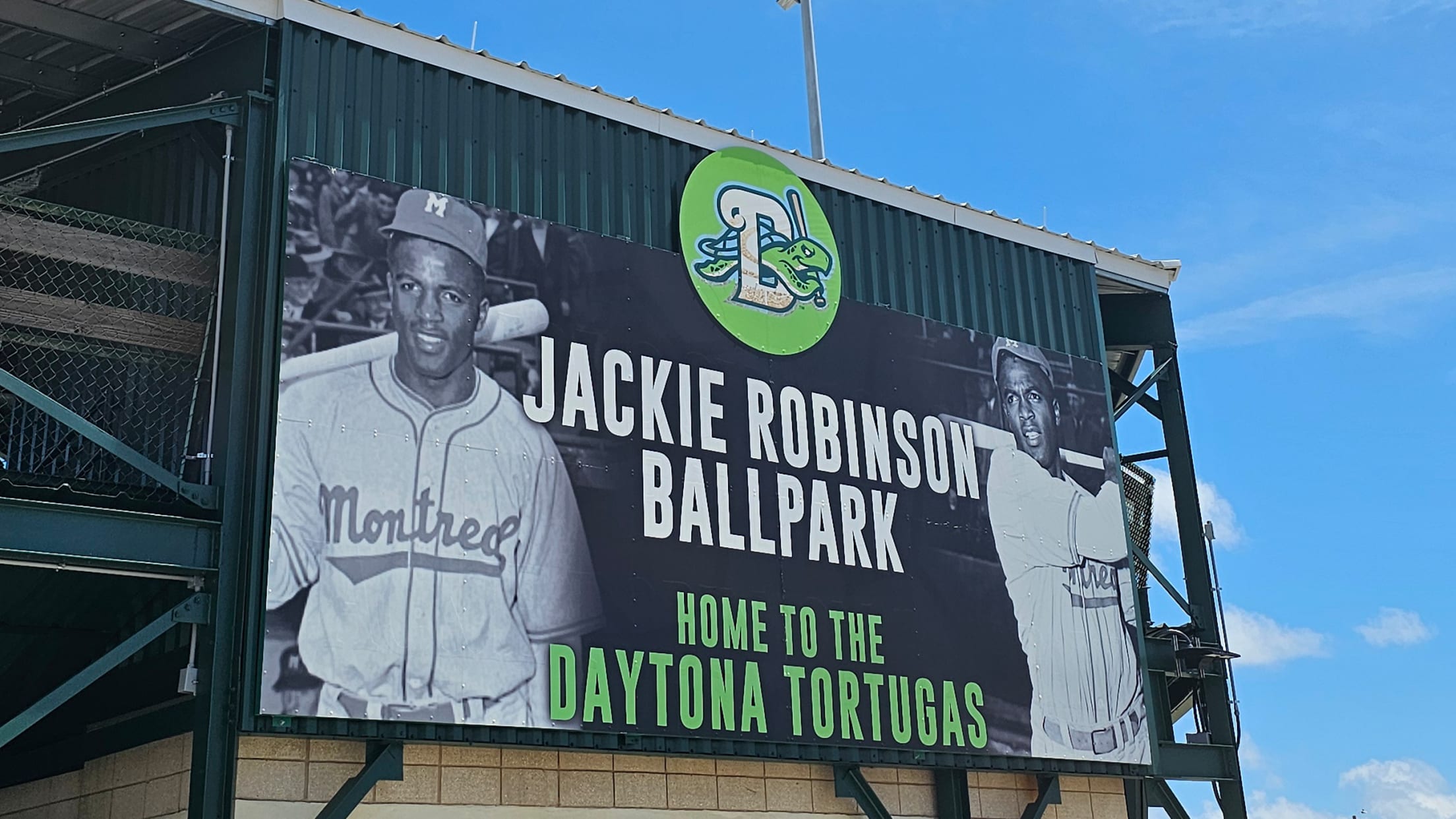

Just a seven-minute drive from our beachside stay at the La Quinta Inn on Daytona Beach’s famous Florida oceanfront, the home of the Single-A Daytona Tortugas first opened in 1914, but its place in the history books was officially written in 1946. It was on March 17 that year that Jackie Robinson played his first Spring Training game as a member of the Montreal Royals, the affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The Dodgers tried to find spring homes for the Royals in Sanford and Jacksonville, only to be turned away. But through the help of Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune – co-founder of Bethune-Cookman University and an advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt – the Daytona City Island Ballpark became Robinson’s first MLB Spring Training home. The park was renamed Jackie Robinson Ballpark in 1990 and remains one of the professional ballparks without a corporate name in honor of the Hall of Famer.

There are parts that look the same as Robinson’s appearance in April 1946, as seen above. Home plate remains essentially in the same place as it sat when the future Hall of Famer took his swings, and the wooden grandstand behind that remains original to the 1940s time period. There’s also a hand-operated scoreboard in left field that is still updated by club employees climbing a ladder, appropriate number in hand.

But updates have come over the years. too. The playing surface has been replaced by an artificial turf field in order to avoid the drainage issues of the past. An interactive Jackie Robinson museum has been put in place just outside the grandstand; among the highlights: fans can test to see if they can match his long-jump record of 25 feet, 6 inches or his basketball vertical of 11 feet, 6 inches. More improvements are coming like new clubhouses and office facilities.

Jackie Robinson Ballpark was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998, and Congressional legislation introduced by members of the Florida designation last April 15 (on Jackie Robinson Day) would designate it a National Commemorative Site on the way to being a National Historic Landmark. The club is hopeful that if that goes through, the money and attention could keep the stadium going for decades to come.

“It’s a balancing act between maintaining the history and keeping Major League Baseball, the Cincinnati Reds and the 21st-century fan happy,” said broadcaster Brennan Mense.

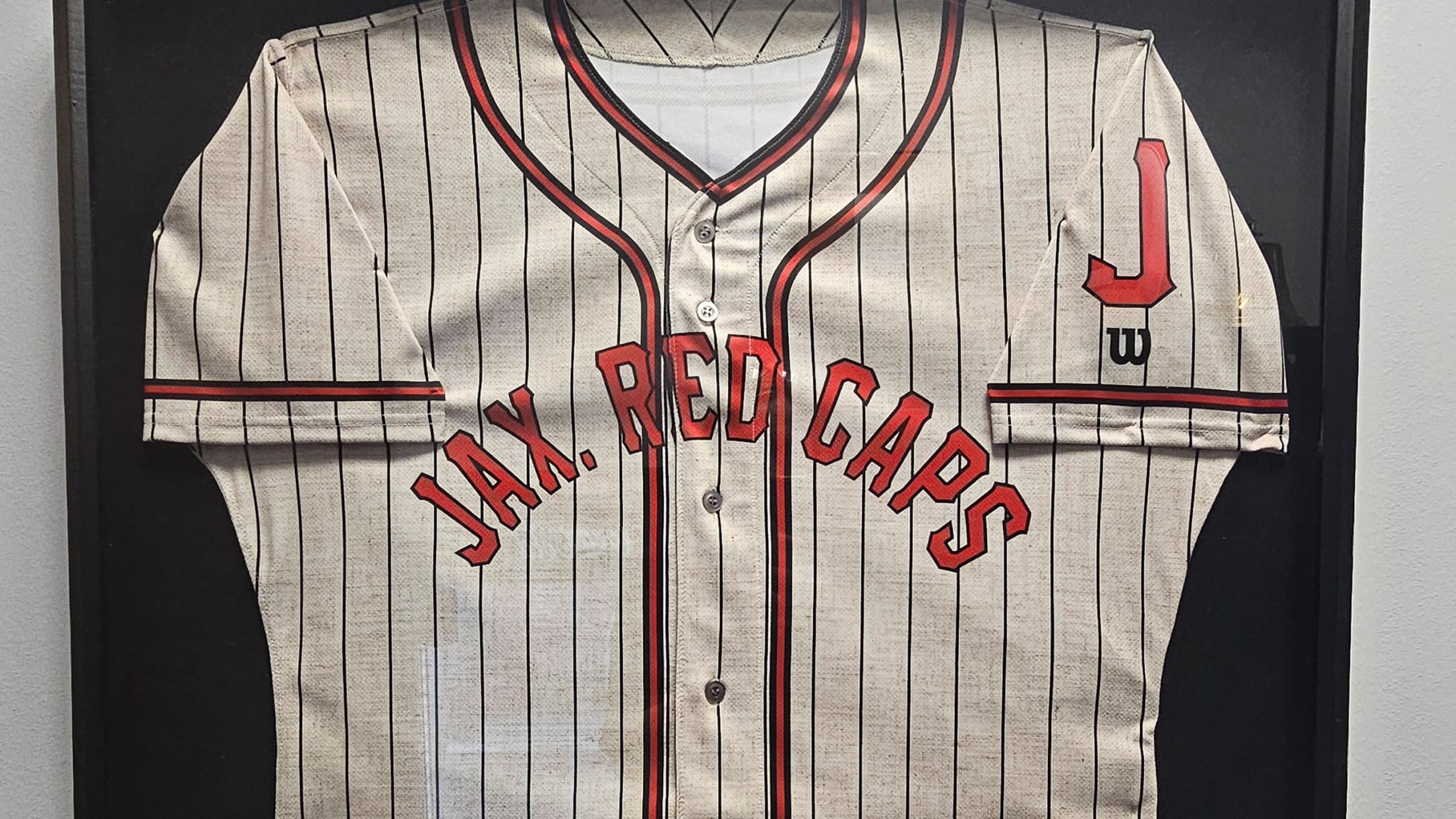

JACKSONVILLE, 121 FINANCIAL BALLPARK

The Triple-A Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp held their Salute to the Negro Leagues Night promotion on Saturday, one night before our arrival. The Marlins affiliate donned pinstriped throwback uniforms with “Jax Red Caps” written across the front honoring the Negro American League that played from 1938-1942 and was named after the hats worn by train station porters. As timing would have it, the club also got cooperation from the visiting Indianapolis side that packed Clowns jerseys for full participation on the field.

It’s an initiative Jacksonville began in 2017 during Harold Craw’s second year as general manager of the then-Southern League club. (The organization joined Triple-A in 2021.) That’s no accident. Craw has a long history of working for Minor League clubs with stops in Johnson City, Charleston, Quad Cities and his native Chattanooga. Along the way, he tried to engage with Negro Leaguers for their good, his good and the community’s good.

Players like Carl Long (Birmingham Black Barons), Clifford Layton (Indianapolis Clowns, New York Black Yankees, Raleigh Tigers) and Harold "Buster" Hair (Birmingham Black Barons, Kansas City Monarchs) became close friends.

“I think for them, it was an opportunity to maybe have a little piece of the game still,” Craw said. “Selfishly for me, it was a way to get wisdom. What did you deal with? How did you deal with that? During your tough times, what did you use? How did you use it? How did you get through those experiences?”

Craw, who became the first Black person to win a Minor League Executive of the Year award when he was honored by the Southern League in 2017, isn’t hoarding those lessons for himself. He wants to pass them along to Jacksonville fans through Red Caps nights and beyond.

“I feel like for us, there's a great opportunity for us to engage all ages,” he said. “When we can offer an opportunity to come here, people think for fun, but then we have an opportunity to educate while they're here. That's a big deal.”

It’s just one way the Jumbo Shrimp can write its own chapter in Jacksonville sports history.

“We know that everything that we're doing moving forward was built on a phenomenal foundation that was here before we got here,” Craw said. “So we just tried to build on that.”

Speaking of which, a seven-minute drive away from 121 Financial Ballpark sits J.P. Small Park.

That brings one question from Craw on our way out.

“Have you talked to Lloyd?”

JACKSONVILLE, J.P. SMALL PARK

Lloyd Washington has been president of the Durkeeville Historical Society since 2011, and according to his biography on the group’s website, his primary commitment is “to preserve and protect Black history in the Jacksonville area.”

One of the key structures in that history is J.P. Small Park.

First built in 1912, the current iteration of the stadium rose from the ashes of a 1936 fire. After being rebuilt, the stadium – then called Durkee Field – became the primary home of the Red Caps for a time and housed Hank Aaron during his 1953 South Atlantic League MVP season with the Jacksonville Braves, Class A affiliate of the Boston Braves. While the ballpark itself is still named for J.P. Small, the actual diamond now bears Aaron’s name – Henry L. Aaron Field, as noted by the outfield scoreboard.

Other renovations have come in the years since, including one that installed a museum that houses various Negro Leagues memorabilia, photos and informational exhibits. A statue of Buck O’Neil – graduate of nearby Edward Waters University – swinging a bat sits outside the brick facade.

But the most important renovation might be the one that is currently ongoing. Estimated at $9.7 million, the project will replace the grass field with a turf one (much like Daytona did), add new fencing, refurbish the dugouts and locker rooms and move the museum to a new location beyond the outfield.

“I can see it being more of a destination,” Washington said of the park that has seen Babe Ruth, Satchel Paige and Rube Foster, among others, come through. “The museum will be on the outside of the ballpark. This area will give them more parking spaces, which is what people will need. My thing is we’ve talked to the Jumbo Shrimp about getting a couple exhibition games out here. These are the types of things we’re looking forward to.”

The return of high school and local college baseball will come first, but Triple-A ball -- for special occasions -- may not be far behind. It sounds a lot like the history and redemption of another former Negro Leagues venue to the northwest.

“This has been a great place to learn history,” Washington said.

More to come from MLB Pipeline's road trip to Rickwood Field through Florida and Alabama.