A lasting impact from a HOF career cut short

The priests summoned to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ clubhouse observed the unconscious outfielder stretched out before them.

It was June 4, 1947, and Pete Reiser appeared to be on death’s door. A short time earlier, he had run into the center-field wall with such speed and force that the Ebbets Field audience let out a collective gasp. Even for “Pistol Pete” -- the nickname Reiser had earned with a bulldog approach to baseball that caused him to crack his head against concrete outfield walls, fall into a ditch and break his leg on a slide, among other mishaps over the years -- this injury looked bad.

In the sixth inning of the Dodgers’ 9-4 win over the Pirates, Reiser had tracked a ball belted off the bat of Culley Rikard. Paying no mind to the cries of “Look out!” that rang from the crowd, he raced toward the wall, stuck up his gloved hand and made the grab just before barreling into the barrier.

Reiser crumpled to the ground. Blood rushed from his head. Teammate Dixie Walker knelt beside him, his white home uniform soon stained red. Then team physician Dominick Rossi arrived to the scene, inspecting the outcome as Reiser lay still. As was uncomfortably custom in his injury-plagued career, Reiser was placed on a stretcher and removed from the field.

“Ebbets Field,” Carl Lundquist of the United Press wrote that day, “was like a cemetery.”

It was, until play resumed, and the crowd took notice of a change on the scoreboard. What had appeared to be an inside-the-park home run, with Rikard trotting all the way home, was changed to an out after an umpire had observed the fallen outfielder.

Reiser was knocked out, but the ball was in his glove.

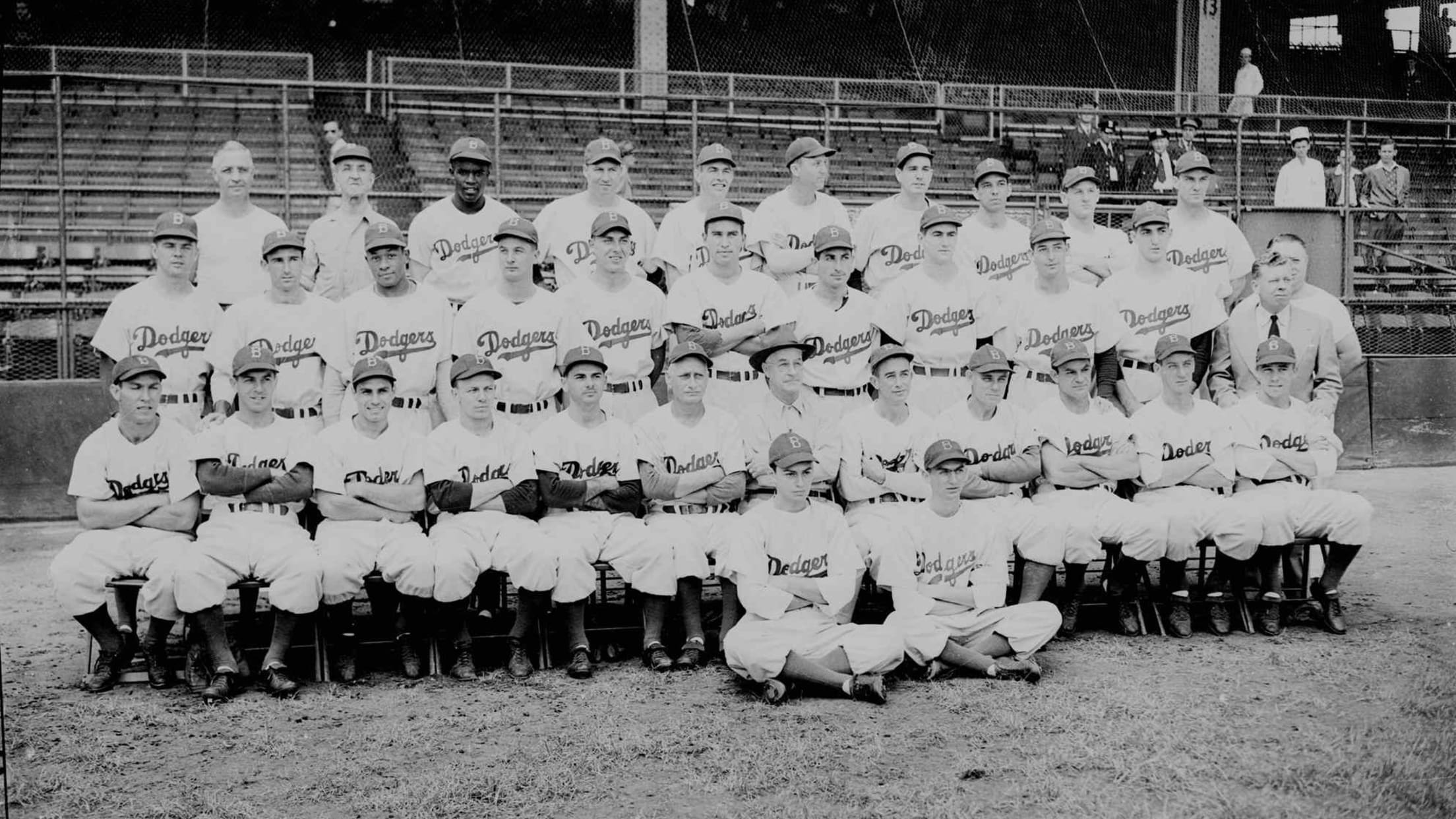

This is the essence of Pistol Pete’s story, jeopardizing life and limb in pursuit of whatever the game required. Some say he could have been an inner-circle Hall of Famer. He was handsome, popular, productive and even ambidextrous. He had a good eye, a great arm and blazing speed. Had he remained healthy, he could have paired with teammate Jackie Robinson, who integrated MLB less than two months before Reiser walloped the wall, to perhaps turn some or all of the Dodgers’ four World Series losses in the late 1940s and early 1950s into victories.

But Reiser’s talent was accompanied by the reckless abandon and ambition with which he crowded the plate, collided with teammates and inanimate objects and returned too quickly from major injuries.

“Pete may have been born to be the best player who ever lived,” the great Red Smith once wrote, “but there was never a park big enough to contain his effort.”

That was certainly the case on June 4, 1947. That’s the day Reiser probably came closer than anyone to joining Ray Chapman, who was felled by a nasty fastball from Carl Mays on Aug. 16, 1920, as the only Major Leaguers to have died directly from a playing injury.

After Reiser was whisked off the field, the two Catholic priests came to the clubhouse to pray over him.

“Through the partially open door,” wrote Dick Young of the New York Daily News, “one priest could be observed in the foreboding administration of the last rites -- it was that frightening, at first.”

Thankfully, Pistol Pete pulled through, albeit with no recollection of the catch. But a once-promising career that was already on wobbly legs on account of the endless injuries was dealt another body blow. After 1947, Reiser would never again play so much as 100 games in a big league season.

Still, Reiser made an impact that is felt -- sometimes literally -- to this very day.

* * * * * * * *

At 5-foot-11, 185 pounds, Pete Reiser was not going to make an impression on anybody with his size.

But his effort always stood out, going back to his time growing up in St. Louis in the Depression era.

“St. Louis was a baseball-crazy town, and Pete had a brother who was five years older who played ball in all these sandlot games,” says author Dan Joseph, whose book “Baseball’s Greatest What If: The Story and Tragedy of Pistol Pete,” was released in 2021. “Pete was 10 and his brother was 15. Pete was playing way above his age, and so he had to play extra hard to keep up.”

The older brother, Mike, was signed out of high school by the Yankees but died of scarlet fever shortly thereafter. Living up to his brother’s expectations and carrying on his legacy became Reiser’s main motivation.

Reiser tried out for his hometown Cardinals at just 15. Though he was not yet old enough to receive a contract, the team hired him as a “chauffeur,” driving around the South with scout Charlie Barrett on his visits to the Cardinals’ farm teams and working out alongside the Minor League players. The Cardinals signed Reiser as soon as they were able, when he graduated high school in 1937.

Then Reiser’s career took a strange turn.

The Cardinals had stockpiled so many young players that Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis ruled it went against the interests of baseball. Landis let dozens of players, including Reiser, out of their commitments to the Cardinals, making them free agents. But Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey did not want to lose Reiser, so he made a secret, verboten deal with a former associate -- Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail -- in which the Dodgers would sign Reiser and stash him in the low Minors for a couple years and then trade him back to St. Louis.

Maybe that plan would have worked, except that Reiser, who became an even more exciting prospect when he switched from hitting right-handed to lefty after signing with the Dodgers to better utilize his speed, was too talented to be stashed.

In Spring Training in 1939, Dodgers player-manager Leo Durocher, who was unaware of the arrangement with Rickey, started telling reporters that Reiser would be his Opening Day shortstop. That angered Rickey, and he gave MacPhail an earful. MacPhail, in turn, had to threaten to fire Durocher to get him to back off his plans to promote Pistol Pete.

So Reiser undeservedly went back to the Eastern League, where he developed bone chips in his throwing elbow and missed much of the 1939 campaign. Healthy again in 1940, he batted .378 in 67 games. It was becoming impossible to justify keeping him down, and MacPhail knew he’d be ridiculed in the press if he dealt Reiser to St. Louis, as planned. Rickey couldn’t exactly complain to the Commissioner’s Office that MacPhail had reneged on the illicit arrangement.

Or maybe MacPhail never planned to let Reiser go in the first place.

“MacPhail hoodwinked Branch Rickey in stealing Reiser from the Cardinals,” asserts author and historian Lyle Spatz in an email interview.

Long story short: Reiser stayed with Brooklyn.

He debuted in the second half of that 1940 season, at age 21, and became Durocher’s go-to bench player. Then, in his first full season, in 1941, Reiser had the kind of year that made it appear as though he might be on a Cooperstown path.

Despite getting beaned twice and crashing into the outfield wall for his first time in the big leagues, Reiser slashed .343/.406/.558 in 1941. His batting average, runs scored (117), doubles (39) and triples (17) all led the NL. Only four other times in NL or AL history has a player led his league in all four of those categories, and the others are all Hall of Famers:

Ty Cobb, AL, 1911

Rogers Hornsby, NL, 1921

Stan Musial, NL, 1946 and 1948

The 22-year-old Reiser was instrumental in the Dodgers winning the NL pennant for the first time since 1920. His inside-the-park grand slam on May 25 was such a seminal moment that, many decades later, it had a cameo in the movie “Captain America: The First Avenger.” Reiser wound up finishing second to teammate Dolph Camilli in the NL MVP voting. He was a sensation.

“Any manager in the National League,” Arthur Patterson wrote in the New York Herald Tribune that year, “would give up his best man to obtain Pete Reiser.”

Reiser seemingly had it all.

What he needed most, though, was a padded wall.

* * * * * * * *

When the Astros moved into what became known as Minute Maid Park in 2000, one of the ballpark’s signature features was “Tal’s Hill,” a 90-foot-wide, 30-degree incline in front of the center-field wall that featured a flagpole and was named for former team president Tal Smith.

The hill was an entirely optional design element. From its inception, it was pretty widely ridiculed as an unnecessary injury risk for outfielders. When it was removed as part of a renovation following the 2016 season, few mourned its departure.

But in Pete Reiser’s era, the type of obstacles presented by Tal’s Hill were fairly commonplace. Flagpoles were in play at many parks. As Joseph notes in his book, Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field not only had a flagpole in front of the outfield wall but a large batting cage in deep center because there was nowhere else to store it. Cincinnati’s Crosley Field had a slope in front of the wall that served as the inspiration for Tal’s Hill. Yankee Stadium had stone monuments to Lou Gehrig, Miller Huggins and Babe Ruth.

“The thing that people don’t realize about Pete Reiser,” says Joseph, “is that he had no protection out there whatsoever. There was no warning track around the base of the wall, and there was no padding on the wall of any kind, not counting the ivy on the Wrigley Field walls. On top of that, there were all these objects in front of the walls.”

So while Reiser was hardly the last player willing to run through a wall for his team, doing so in his day came with much bigger consequences than in today’s game.

Reiser demonstrated this the hard way on July 19, 1942, at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park.

He was batting .350 and had just completed a 13-game hitting streak, further lending credence to the belief that he was blossoming into one of baseball’s very best. But in the 11th inning of the nightcap of a doubleheader, with the game tied 6-6, Reiser raced toward the center-field wall, barely avoided a flagpole and smacked into the concrete wall immediately after catching an Enos Slaughter fly ball.

The ball fell from a dazed Reiser’s glove, and he threw it to the cutoff man before collapsing to the ground. As Slaughter ran all the way home to win it for the Cardinals, Reiser lay motionless on his back with blood trickling from his ears. Durocher saw him and started to cry.

Diagnosed with a separated shoulder and a brain injury, Reiser was advised by the Dodgers’ team physician not to play again that season.

“I don’t like hospitals, though,” Reiser told the men’s magazine True in 1958, “so after two days I took the bandage off and got up. The room started to spin, but I got dressed and I took off. I snuck out, and I took a train to Pittsburgh and I went to the park.”

Reiser was back in the Dodgers’ lineup just six days after suffering that concussion. He was never again the same player. In his final 48 games that season, he hit .244 with a .680 OPS.

“I’d say I lost the pennant for us that year,” Reiser said in the True piece. “I was dizzy most of the time and I couldn’t see fly balls. I mean balls I could have put in my pocket, I couldn’t get near.”

Reiser did not have long to examine the effects of that injury on his big league career, for in 1943 he was drafted into the Army as part of the World War II effort. At Fort Riley in Kansas, Reiser contracted pneumonia during a march in below-zero weather and nearly received a medical discharge. But his base commander instead assigned him to the camp baseball team, where he played for the next two years.

It was there that Reiser chased a fly ball through a thick hedge that served as an outfield “wall” and fell down a 10-foot drainage ditch. He separated his right shoulder on that accident, so he switched gloves and started throwing with his left arm instead.

In 1945, an Army doctor reviewed Reiser’s medical records and could not believe he had even been allowed in the service in the first place. This time, Reiser received his medical discharge and rejoined the Dodgers for the '46 season. By then, the 27-year-old Reiser’s arm was shot, but he could still hit and still run. He wound up stealing an MLB-high 34 bases that year, including seven thefts of home.

The injuries, though, kept coming. Reiser reinjured his shoulder, ran into a wall (again) and even, away from the field, burned his hands lighting an oven. His 1946 season ended prematurely when he fractured his leg on a stolen-base attempt.

Spatz, a young Dodgers fan at that time, is among the few still with us who saw Reiser play in person.

“I guess I expected the Reiser I had heard and read about,” Spatz writes in an email. “But I never got to see him hit a home run or steal a base. I think most of the adult fans realized he was ‘over the hill.’”

Whatever hope remained that Reiser could reclaim his past promise dissipated for good on that fateful day of June 4, 1947 -- the day he was administered the last rites. After that incident, Reiser drifted in and out of consciousness for several days and spent three weeks in the hospital. Upon his release, he traveled with the Dodgers, only to collide with teammate Clyde King in the outfield during a pregame workout. Afterward, he felt a lump on his head, got it checked out and discovered he had a blood clot that required emergency surgery.

Somehow, Reiser managed to play 110 games that season, and he played in five games of the Dodgers’ 1947 World Series loss to the Yankees. But he misplayed two balls in the first two games of the Fall Classic and injured his ankle on a stolen-base attempt in the third. He was a bench player for the remainder of the Series and for the remainder of his career.

In Reiser’s career, which ended with Cleveland in 1952, he hit .295 with an .829 OPS, 58 homers, 155 doubles, 41 triples and 368 RBIs. But then there are the unverifiable stats that aren’t in his Baseball Encyclopedia entry. Reiser is said to have suffered seven concussions. And while it’s probably not accurate that he was carried off the field on a stretcher 11 times, as has often been written, that number is probably not far from the truth, either.

If not for the injuries, perhaps more people would have shared the opinion of Durocher, who in his autobiography, “Nice Guys Finish Last,” was effusive in his praise of Reiser.

“There was only one other player comparable to Pete Reiser: Willie Mays,” wrote Durocher, who was Mays’ first manager with the Giants. “Pete had more power than Willie -- left-handed and right-handed both. Willie Mays had everything. Pete Reiser had everything but luck. Pete Reiser just might have been the best baseball player I ever saw. He could throw as good as Willie, and he could throw right-handed and left-handed. You think Willie could run? You think Mickey Mantle could run? Name whoever you want and Pete Reiser was faster.”

Every baseball fan knows the name Willie Mays. Relatively few have heard of Pete Reiser. But his legacy is embedded into the vinyl or polyurethane padding that now lines the outfield walls.

* * * * * * * *

Reiser was not unaware of the risk he was taking with his audacious approach to baseball.

“When people tell me I played too hard,” Reiser once said, “I tell them that’s how I got up to the Majors.”

Reiser, though, reached the Majors in a home park that was an especially terrible fit for his style. As Joseph points out in his book, because Ebbets Field was crammed into a city block, its deepest point in center field and its left-center and right-center-field walls were among the shortest distances from home plate in the Majors. That didn’t give Reiser much real estate to work with. And the unpadded walls and an iron exit gate (on which Reiser once cut his back while chasing down a fly ball) were unforgiving.

Inspired by Reiser -- but too late to save him -- Ebbets Field was one of the very first ballparks to usher in safety measures that are now standard in the sport.

Though Forbes Field is believed to be the first ballpark to pad its walls in the late 1930s or early 1940s, Ebbets appears to have been the second. Branch Rickey, who reluctantly lost Reiser during his stewardship of the Cardinals, had him back under his employ when he assumed the Dodgers’ general manager position from Larry MacPhail in 1943. And in 1948, mere months after Reiser’s near-death experience at Ebbets, Rickey ordered the outfield walls be padded with foam rubber.

Soon after, narrow cinder warning tracks were installed at Ebbets, Wrigley Field, Boston’s Braves Field and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. By July 1949, 10-feet-wide warning tracks were formalized for all MLB ballparks.

The effectiveness of warning tracks, which really aren’t wide enough to properly warn hard-charging outfielders of the fast-approaching wall, is debatable. But the padding definitely helps. And though there were some notable holdouts (the walls at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium were not padded until 1992, and Wrigley and its ivy-covered walls are grandfathered out of the now-mandatory padding requirement), the standardization of these player-safety measures was inspired by Reiser’s horrific collision in ’47.

The Dodger who could not dodge walls went on to manage in the Minors before joining Dodgers manager Walter Alston’s staff in Los Angeles in 1960. Reiser won a World Series ring in 1963, and his work with Maury Wills was instrumental in Wills becoming the top stolen-base threat in the game at that time. Reiser also coached for Durocher’s Cubs and for the Angels.

Reiser passed away from respiratory disease in 1981, at the age of 62. That same year, authors Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig boldly included him in their book, “The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time,” on the premise that he was one of the most superbly talented people to have ever stepped between the lines, regardless of how the injuries curtailed his career.

Of course, there are many others -- José Fernández, Smoky Joe Wood, Herb Score, Grady Sizemore, Eric Davis, Mark Fidrych, J.R. Richard and on and on -- who had Hall of Fame-caliber talent offset by injury or tragedy. But as Joseph writes in his book, a healthy Reiser would have been particularly well-positioned to leave a lasting impression on the game.

“He wasn’t just a great young baseball player,” Joseph writes. “He was set to become a central figure in the national pastime. He was in the right place at the right time -- New York, baseball and media capital of the world, at the start of the most drama-filled period in the game’s long, long history.”

Alas, we remember Reiser more for being carted off the field than for the talent he displayed on it. But we can think of him every time outfielders slam into a padded wall in pursuit of a ball.

Pistol Pete’s career died so that theirs could live.

* * * * * * * *

Dan Joseph’s book “Baseball’s Greatest What If: The Story and Tragedy of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Pistol Pete Reiser” is available from Sunbury Press.