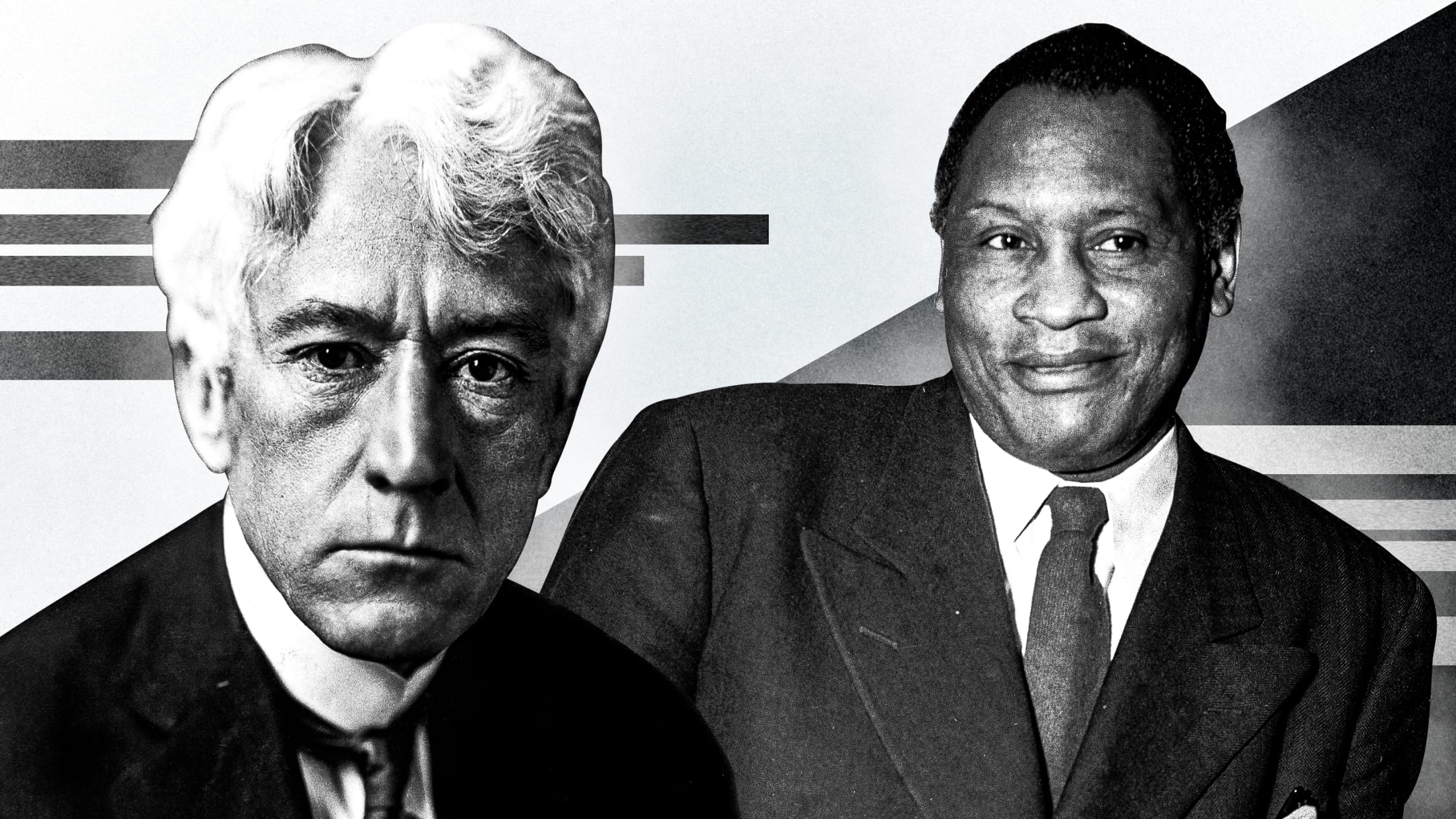

When Paul Robeson and Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis met

A version of this essay was first published in July 2020 when a group of MVP winners publicly objected to the award being named in honor of Kenesaw Mountain Landis. While the minutes of Major League Baseball’s league meetings are held closely, this particular document, from December 1943, had been donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame, which permitted public access.

Read the essay in that context, please. This was the centennial year of the founding of the Negro National League; an epidemic was raging; and the murder of George Floyd produced a movement, with associated protests, that may be termed Black Lives Matter.

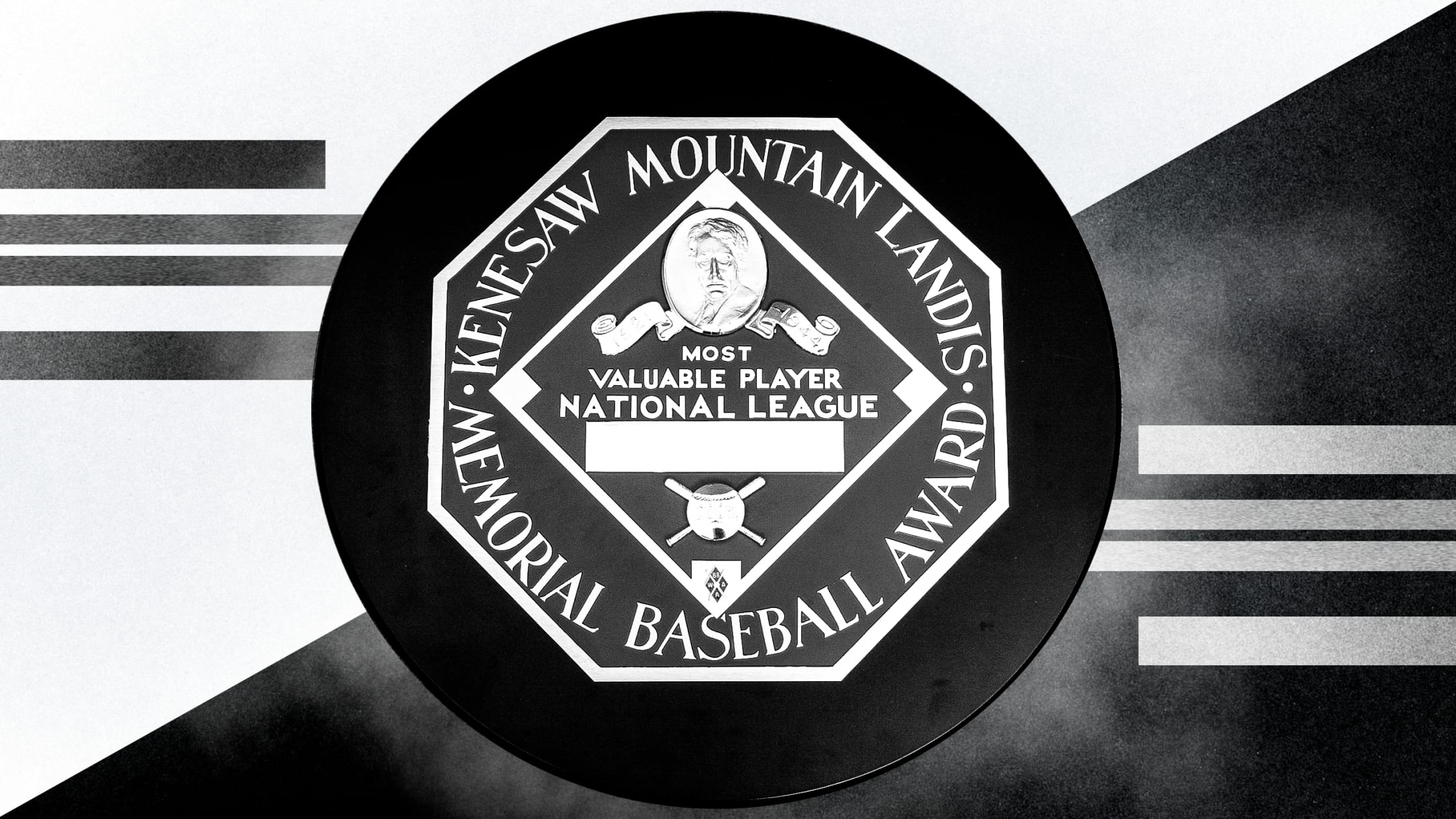

In baseball, too, there was a heightened racial sensitivity. Following publication of this essay, the Base Ball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) removed Judge Landis’ name from the MVP plaque and then, in February 2021, renamed its annual award for best career writing about the game, from the J.G. Taylor Spink Award to the BBWAA Career Excellence Award. The racism of these two men, seen in retrospect but newly understood, led the writers to their conclusions.

Between these two decisions, Commissioner Manfred issued a statement on December 16, 2020, that recognized seven Negro Leagues of 1920-48 as Majors, equivalent to the National and American leagues. It was in this age of heightened awareness that the story was written and, the writer hopes, it will now be read.

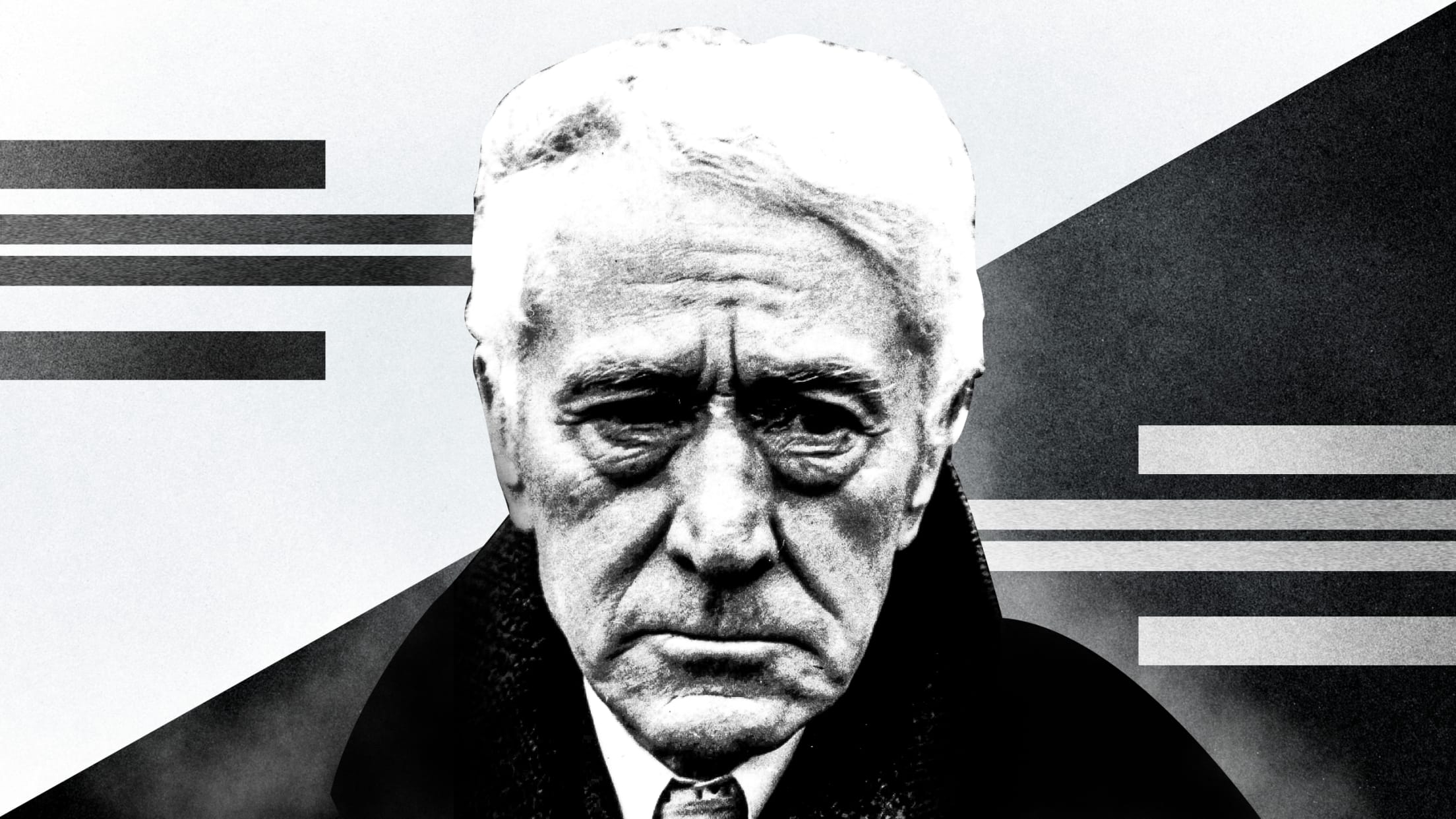

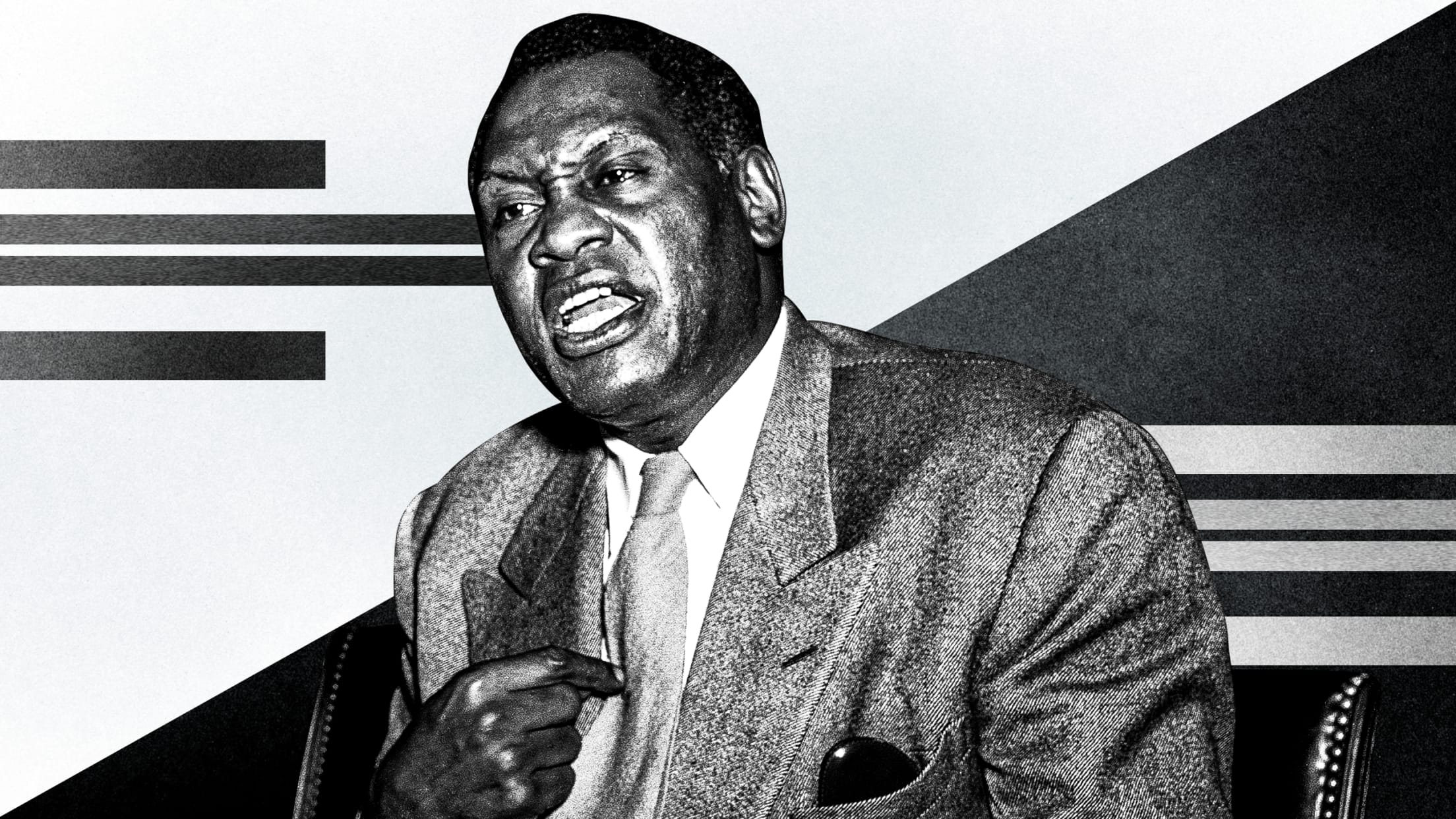

For younger readers especially: Judge Landis was Baseball’s first Commissioner, holding office from 1920 until his death in 1944. Paul Robeson was an All-American football player, Lou Gehrig’s baseball coach at Columbia University, a star of stage and screen, and an advocate for social justice.

---

When Landis took the Commissioner post in 1920, the owners were desperate to save the game from a public perception of rigged outcomes, as had threatened boxing and horse racing. Everyone in baseball’s upper echelon knew that the Black Sox had thrown the World Series, even if widespread recognition took nearly a year to solidify. The sixteen club owners were looking for a strong hand at the helm and they granted Landis unprecedented control over the game. [I wrote on this subject for the New York Times.]

Landis could have broken the color bar in the 1920s, when he ruled the game with an iron fist and owners feared crossing him. His powers over them waned with the economic woes of the 1930s; by then he may well have felt more constrained — that he had to go along with a broad national sentiment against racial integration. Then again, the onset of World War II might have persuaded him otherwise. “If we are able to stop bullets, why not balls?” was the excellent question posed on rally placards.

In sum, my view is that it doesn’t matter to me, nor should it matter to anyone, whether Landis harbored racist thoughts or feelings, or uttered a demonstrably racist sentence. What matters is what he did or did not do, in an office in which for a long time he held unfettered sway. Racism is as racism does.

On December 3, 1943, the joint meeting was to have opened with presentations by John Herman Henry Sengstacke, president of the Negro National Newspaper Publishers Association; Ira Lewis, publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier; and Howard Murphy, secretary of the Negro National Newspaper Publishers Association. But because Paul Robeson had to get to the Shubert Theater for rehearsals of "Othello," he was permitted to address the group first. Below, a transcript of Robeson’s appearance before Landis and representatives of the sixteen clubs.

COMMISSIONER LANDIS: The meeting is called to order.

Mr. Sengstacke, I am interfering with your plans just a little. I have brought Paul Robeson here.

I don’t need to introduce this man to you gentlemen. When he comes into a meeting, there is no thing that I recognize that has any relation to intolerance or lack of forbearance, or to racial controversy. I brought him here on my own invitation -- now, you understand that, don’t you, Sengstacke? I told you that I was doing that -- because this man has sense, and this man has not been fooled by the propaganda that there is an agreement in this crowd of men to bar Negroes from Baseball.

[In 1942 Leo Durocher had been quoted in the Daily Worker as saying that “a grapevine understanding or subterranean rule” barred Black players from baseball. On July 30 of that year, Brooklyn’s president Larry MacPhail added, “Judge Landis was not speaking for baseball when he said there is no barrier: there has been an unwritten law tantamount to an agreement between major league clubs on the subject of avoiding the racial issue.” — jt]

I don’t know what, beyond that, he understands, but I am informing him and these other men that are here with you, Mr. Sengstacke, of this: I have been here only twenty-three years, and maybe I don’t know what is going on — I don’t know; I won’t testify to that; but, so far as I know, and from all I have learned in twenty-three years, there is no such agreement.

God knows these men are not cowardly enough to be afraid to put it on paper, and to have it as a haymow agreement; and I am not crook enough to stand up and enforce such a haymow agreement. [“haymow” referencing a barnyard outbuilding in which hay was stored — jt]

Now, do you understand that?

SENGSTACKE: Yes, sir.

COMM. LANDIS: With respect to that question, these clubs are on their own. Have that in mind in presenting this question.

You go ahead and talk, now, Robeson.

PAUL ROBESON: I want to thank Judge Landis for permitting me to say a word to you gentlemen. I would say before I begin that I come as one who is an athlete himself, and as an American. And I can in no way disassociate myself from my friends around here. I came up with them. They represent the Negro Publishers Association, and have, perhaps, more definite knowledge of the problem about which you would want specific questions -- for example, as regards Negro ball players -- than I would have. There are many distinguished Negroes in the room.

I come only because I played a lot myself, and because I feel very deeply about this problem of getting Negro ball players into the leagues.

I played against Frankie Frisch when he was at Fordham, and I was a catcher at Rutgers. I was just telling the Judge that, when I was a catcher, we had a pitcher who wound up pretty slowly, and by the time I drew back, Frisch was practically around second.

I later coached at Columbia, when Gehrig was playing. I, as you know, was an All-American football player, and played pro football.

Problems have come up that face you owners and managers. Judge Landis has said -- you have heard him say -- that there is no agreement against Negro ball players. However, we know the problems that must confront you when the question comes up: Shall we hire Negro ball players?

First, there is the question: Shall other players play with them? I know about that from my own experience. I have played with Southern boys in football. At first they wouldn’t play, but at the end of the game every man shook my hand.

When I went to play pro out in Akron, years later, the first fellows that greeted me were from the South.

As far as the public is concerned, certainly we have seen in various sports -- in boxing, in football, again, and in track -- that the American public is ready to accept Negro athletes.

I have had great experience showing what can happen in America today. I am playing Othello -- and there were bets that could not be done in America. I have done it in Boston; I have done it in Philadelphia; we are now a smash hit on Broadway. And I can think of no greater acclaim that I have ever received than I do every night in this theatre -- a real demonstration to me of what the American democratic spirit can mean.

You face, I know, serious problems. There is no question about the quality of the ball players; there are plenty of them around. You need ball players, and it has gone beyond, I think, the question of letting it slide.

Some say it is going to be a difficult problem. Well, we live in difficult times; we have to take up difficult things, and show that we stand foursquare on what our country can mean.

I never presumed that there was any agreement among you gentlemen to bar Negro ball players, but merely that you hate to initiate a policy that has not been initiated before. We live in times when the world is changing very fast, and when you might be able to make a great contribution to not only the advance of our own country, but of the whole world, because a thing like this -- Negro ball players becoming a part of the great national pastime of America -- could make a great difference in what peoples all over the world would feel toward us as a country, in a time when we need their help.

As I say, I speak purely as an individual, and as a former athlete. My son, who, I think, is going to be a swell pitcher, is already a swell fullback and playing in the league that [Angelo] Bertelli came from, up around Springfield, Massachusetts -- so you know it is a good league -- and he is throwing his forward passes and catching them; and I would like to think that if he wanted to play baseball and was good enough, like Frisch or Gehrig, he could play. [Bertelli won the Heisman Award in 1943, then joined the Marines for 1944.]

I played pro football myself. I don’t know why colored fellows aren’t in the pro football leagues. I would probably feel, if I were playing today, that I could go to Halas, Conzelman, and other fellows that I played with, and say, “Give me a chance to play some football.” So I think I could ask for a chance to play baseball.

I have played in most of the parks, either in football or something else, all over the country, and I sense a different spirit today. I hope that something can be done.

I sincerely hope that the Judge will permit the other Negro representatives, who really know much more about this than I do, to say a few words.

Thank you, Judge.

COMM. LANDIS: We are much obliged to you, sir. (Applause)

COMM. LANDIS: You go ahead, now, Mr. Sengstacke. You want to talk, don’t you?

[Sengstacke proceeds to read a statement, which is followed by prepared remarks from Ira Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier and Howard H. Murphy of the Baltimore Afro-American. These may be read here. Also in attendance though not presenting were Wendell Smith of the Courier, Dan Burley and Dr. C.B. Powell of the New York Amsterdam News, Louis E. Martin of the Michigan Chronicle, and William O. Walker of the Cleveland Call Post.]

COMM. LANDIS: Has anybody any question? (No response) [i.e, from AL or NL club delegates]

Apparently, there are no questions.

SENGSTACKE: Thank you very much, Judge Landis.

***

I agree with the late great scholar Jules Tygiel on this: “While hypocritically denying the existence of any ‘rule, formal or informal, or any understanding -- unwritten, subterranean, or sub-anything -- against the signing of Negro players,’ Landis had stringently policed the color line. His death in 1944 removed a major barrier for integration advocates.”

The wink-and-nudge display of that hypocrisy for me constitutes the documentation that Landis defenders have requested. Dodgers Leo Durocher and Larry MacPhail had stepped out of line and had to be pulled back in. This extract from the end of the meeting — a discussion with Branch Rickey about how to characterize the presentations by the integration advocates — is especially illuminating.

Consider also Landis’s response to Rickey’s suggestion, at the meeting’s conclusion, that Baseball as an organization had taken no action:

With all owners except Rickey silent on the question of race, Landis reiterated that the major leagues had no policy against admitting Black players, that it was left to each of the clubs to decide. This forms an exemplar of Landis’s method of skirting personal responsibility, whether from personal or legal concern. I believe that Rickey’s resolve to bring an African American to the major leagues -- a resolve born long ago, when he was a student at Ohio Wesleyan-- was confirmed in this exchange with Landis on December 3, 1943:

RICKEY [Brooklyn]: Mr. Commissioner, are we to understand that the report from this meeting, in response to the delegation that came in here today, is to be simply that the matter was not considered?

COMM. LANDIS: No, no. The announcement will have to be that it was considered -- and my recollection now is that it was considered, and you gentlemen all remember that it was considered; you each participated in the consideration of it -- and that no action was taken on it; that the matter is a matter for each club to determine in getting together its baseball team; that no other solution than that, in view of the nature of our operations, is possible.

Do I state what you have in mind?

BREADON [St. Louis NL]: Yes, sir.

RICKEY: I thought that we should all have in mind the same thing.

COMM. LANDIS: Yes. Is there anything more, Mr. O’Connor [Landis’s assistant]?

O’CONNOR: No.

RICKEY: Mr. Commissioner, there is one further step for our consideration on that matter. Some of our clubs are beset with a great many petitions and a great many visitations, such as you saw here today. That they become embarrassing is not the point; they become time-taking, and, from a publicity standpoint, they become important.

Is it in order for a club to say that this is a matter requiring not only our League consideration, but joint consideration, and that the club itself is not able to give any further statement than it has now given, whatever that is?

Is that the position? Is that a good position to take? Is it permissible or advisable for us to make that statement?

COMM. LANDIS: I don’t think it is, for this reason: that three Major League managers were quoted in Negro newspapers as saying that, but for the bar, there would be a foot-race run by sixteen Major League managers to sign up Negro ball players.

I called in those three managers, and, while there was no admission that they had made those statements, I think it is a fair approach to the truth to say that, such was the unconvincing quality of their evasiveness in reply to my questions, they all did make the statement.

Whereupon, I gave out an announcement a year ago last summer that any club was perfectly at liberty to hire one or twenty or twenty-five Negro players. I gave out that statement: that there never had been agreement, written or unwritten, vocal or otherwise, and that each club was absolutely and completely at liberty in that respect, as they were in respect of any other players coming from any other race or belonging to any particular church or anything else.

I think your suggestion would carry with it an implication that they were not at liberty; that it would require League action -- and I don’t think that would be good. I think that would be indefensible.

RICKEY: It was hardly a suggestion, Judge; it was an inquiry.

COMMISSIONER LANDIS: Well, it was an inquiry, but suspicious men might think that--

RICKEY: Yes, that is right.

COMMISSIONER LANDIS: I don’t think anybody ought to say that. We can’t say that. In the first place, it isn’t true, and, if any of you gentlemen want to hire a Negro player, you are as much at liberty to do that as you are to sign up any other player, be he in human form. That is our whole theory, and we must keep away from the other idea….

[Rickey offers nothing further, and upon a motion to adjourn from Clark Griffith of the Washington club, the meeting, which had commenced at 10:30, ends at 12:40.]