1979: The year that Orioles Magic began

HARMONIC CONVERGENCE: a term applied to a certain planetary alignment which was said to be a global awakening to love and unity.

Thirty years ago, the Orioles embarked on a season that would mark a turning point for the franchise. Off the field, the team began its second quarter-century in Baltimore facing a change in ownership. On the field, a young corps of players was blossoming into the foundation of a pair of World Series teams.

The Orioles finished first or second in the AL East in 10 of 11 seasons from 1973 through 1983. The lone exception was 1978, when they finished fourth despite winning 90 games.

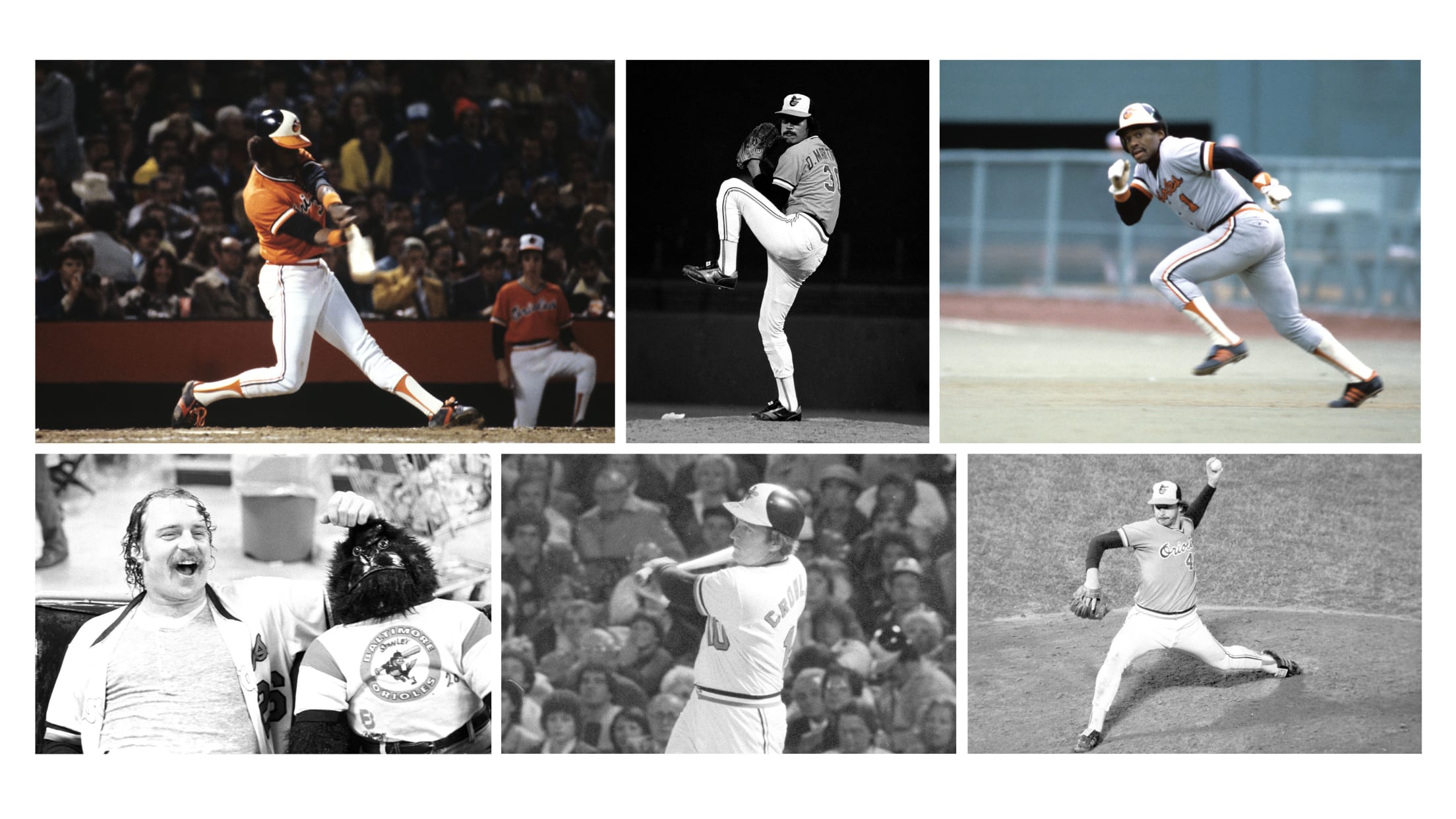

But after winning division titles and losing in the playoffs in 1973 and ’74, the Orioles began to retool. A 10-player trade with the Yankees in 1976 netted Scott McGregor, Tippy Martinez, and Rick Dempsey, who joined recent farm system products like Mike Flanagan, Dennis Martinez, Rich Dauer, and Eddie Murray – all of whom were in just their third or fourth season in the majors. Veteran holdovers including Jim Palmer, Doug DeCinces, Lee May, Mark Belanger, Al Bumbry, and Ken Singleton blended with new or recent additions like Gary Roenicke, John Lowenstein, and Don Stanhouse. Veterans like Pat Kelly and Terry Crowley provided manager Earl Weaver with what he liked to call “deep depth” on the bench, while there was room for rookies like Sammy Stewart and Tim Stoddard on the pitching staff.

“We were a young team,” recalled Flanagan, who went on to win the Cy Young Award that year. “I looked it up once, we averaged 27.3 years of age, which is even younger than the team now. We won 90 games the year before but finished fourth and were never even a factor. So here we were coming off that year, and I think we were ready.

“But there was so much about that season,” Flanagan said. “The club really connected with the town for some reason. It was the perfect aligning of the stars.”

The ’79 Orioles lived up to Weaver’s oft-quoted preference for “pitching, defense, and three-run homers.” As a team, the Birds finished eighth in the American League in runs scored (757) and 11th in batting average (.261). But they set a team record and finished third in the league with 181 home runs.

And while the Orioles always were known for their strong pitching, never – not even in the heyday of Palmer-McNally-Cuellar – did they dominate the league like they did in 1979. Their team ERA of 3.26 was more than a half-run better than runner up New York (3.83). They allowed only 582 runs – 90 fewer than the Yankees – and the fewest hits (1279) while holding opponents to a league-low .241 batting average.

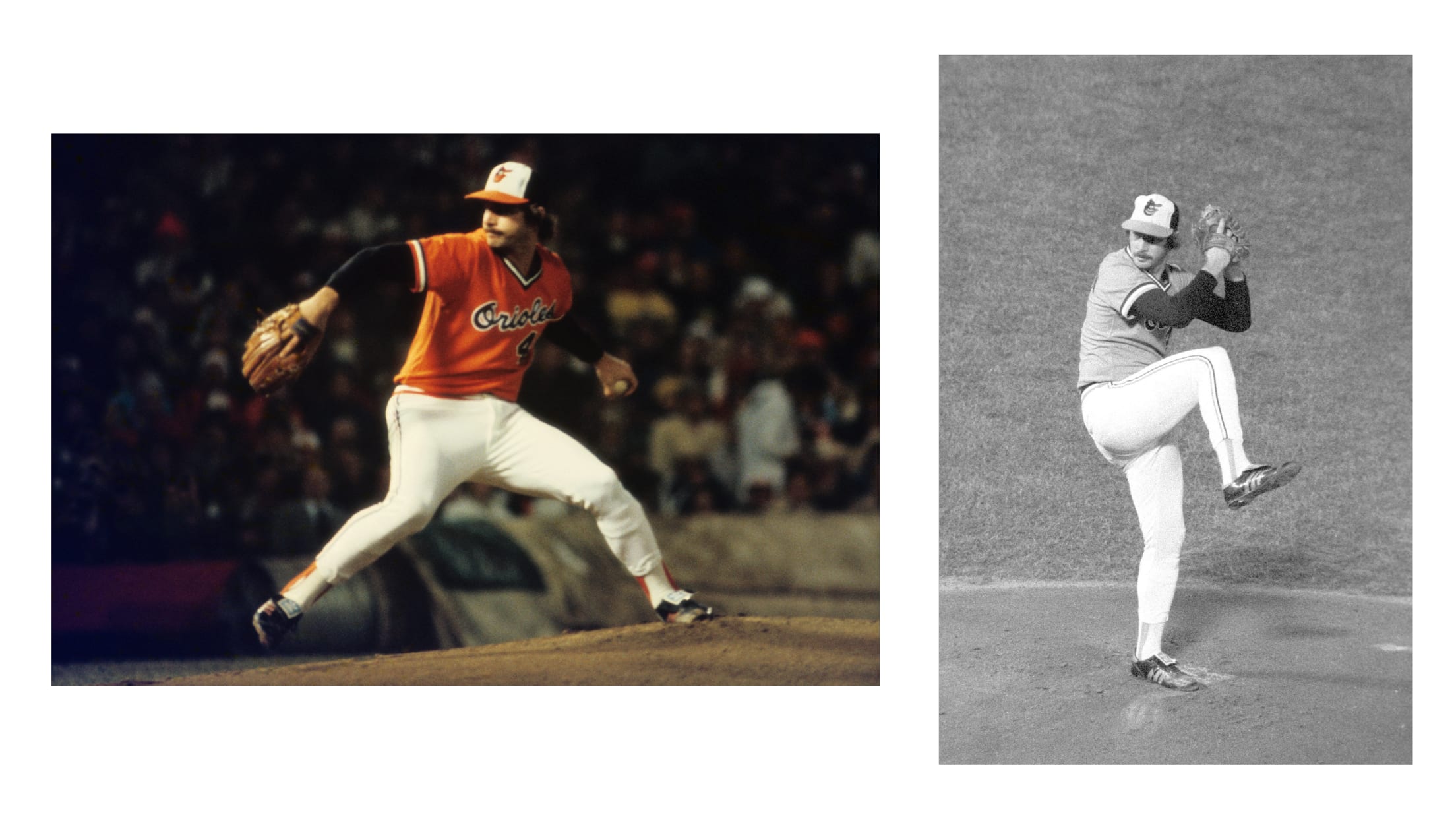

Not even injuries to Palmer and McGregor could stymie the starting rotation. Flanagan went 16-4 starting June 17 and posted a 2.01 ERA over his last 11 starts, a stretch including six complete games. The lefty won the Cy Young Award after finishing with a 23-9 record, leading the league in wins and finishing in the top five in four other categories.

“Flanny was amazing,” Dempsey said. “You just couldn’t score off him. He would grind it out, and you couldn’t take him out of the game, he just kept trucking out of the dugout inning after inning. He threw 140 pitches in a game several times. He had five different pitches, and he knew when to throw each of them to make it most effective.”

“Scotty worked with me on a changeup before that season,” Flanagan said. “I adopted a version of his and I think it fooled the league some when I started using it.

“But we had a great staff. We used five starters and four relievers (most of) that season. We had four (starters) among the top 20 in the league in ERA. Dennis (Martinez) pitched a ton of innings (295) and led the league with 18 complete games, and still had a losing record (15-16).”

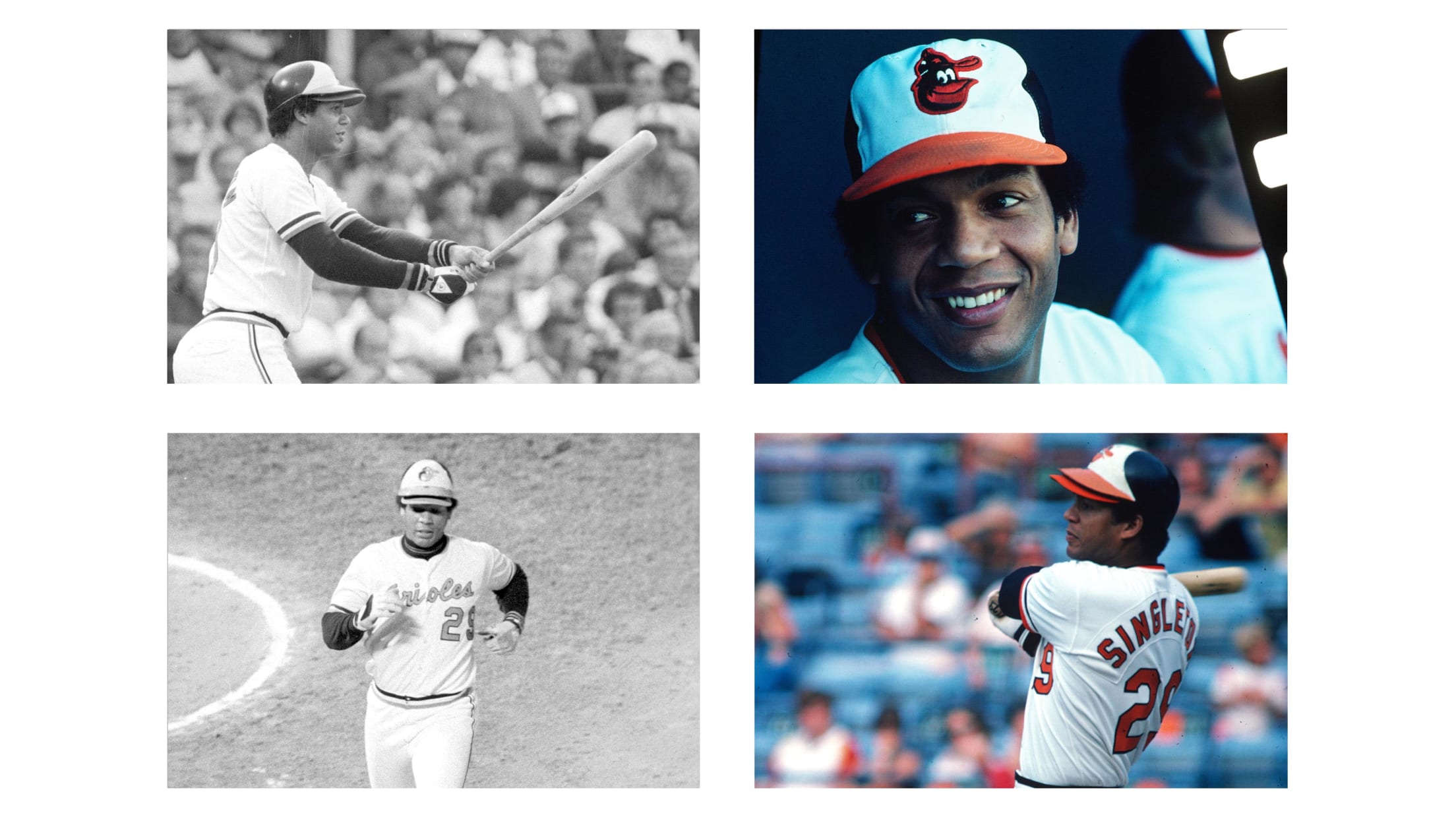

Singleton finished second behind the Angels’ Don Baylor for the AL Most Valuable Player Award, leading the club with career-highs of 35 home runs, 93 runs scored, and 111 RBI while batting .295. His home run and RBI totals were good for fifth and sixth in the league, respectively.

“I remember when we clinched the division, during the clubhouse celebration, and DeCinces said ‘You know you’re the MVP right?’ And I really hadn’t thought about it to that point,” Singleton said. “We really were all about team. And then after the season ended, before they announced the vote, I went to a banquet out in the L.A. area, and Sparky Anderson introduced me as the American League MVP. I knew then that I wasn’t gonna win it.”

All of the collective and individual numbers led to a 102-57 record, best in the American League. But those numbers don’t really tell the story.

That season, the Orioles had switched from their long-time radio partner to a new outlet, WFBR-AM, a top-40 music station which had a younger, hipper audience. WFBR promoted the ballclub like never before, not only with new pre-game and post-game shows, but throughout the day by its disc jockeys. Led by morning DJ Johnny Walker, the station featured highlights from the previous night’s game as part of its regular programming, with home runs, defensive gems, and key strikeouts cut into the song “Orioles Magic”.

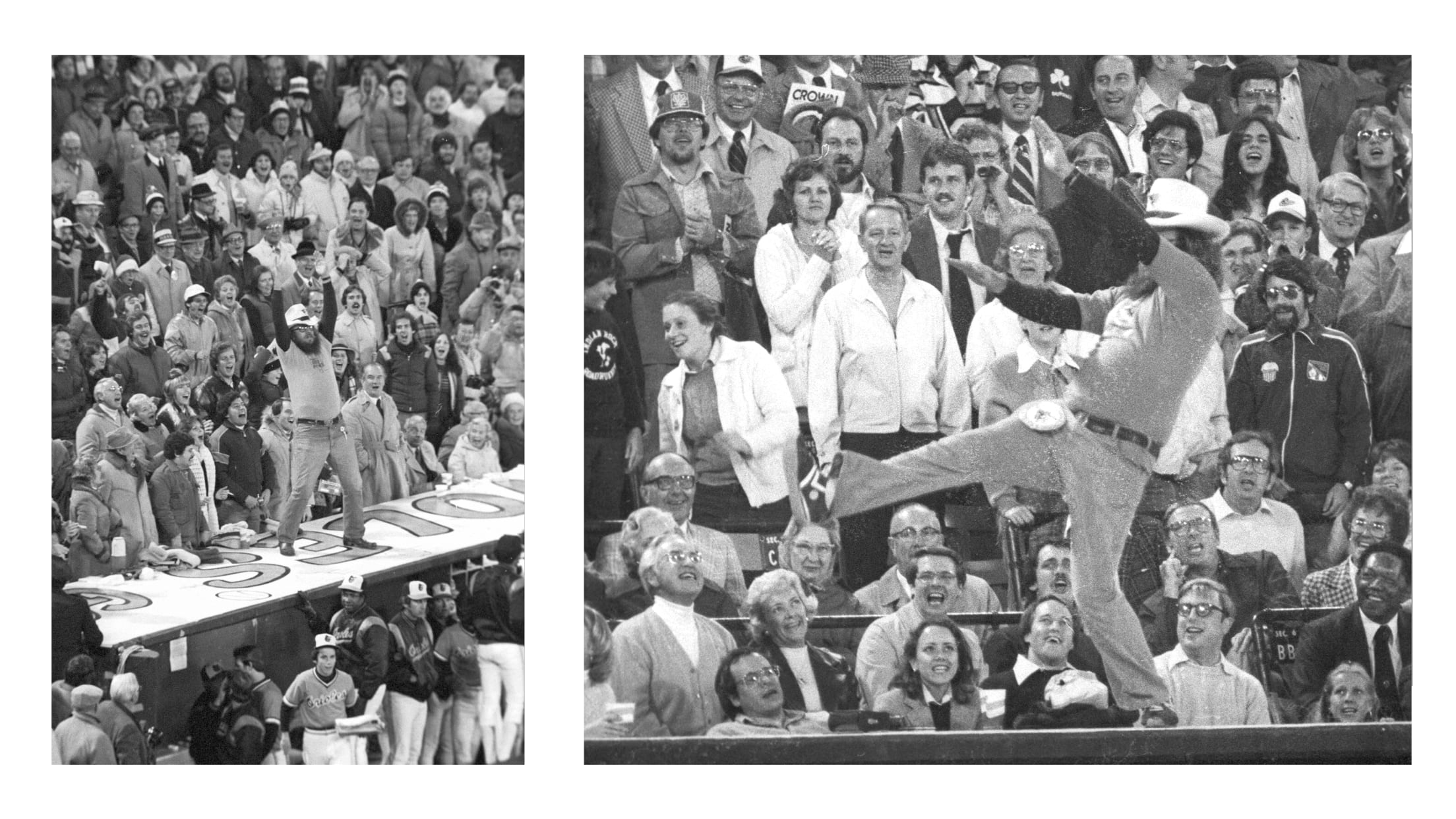

At about the same time, part of that younger, hipper audience was creating a foothold in Section 34 of Memorial Stadium’s upper deck. Down the right field line, these fans – led by a cab driver in a cowboy hat named Wild Bill Hagy – brought unbridled enthusiasm (not to mention lots of beer and other potables) to the stands. Many of the people listening on the radio began showing up at the ballpark. The young team fed off this new young audience, and it all came together in its own kind of harmonic convergence that built through the summer months.

If a season can be defined by one game, it is not hard to pick the one that gave the Orioles their identity: June 22, 1979. It was a game that came to epitomize not just the season, but an era and, perhaps, the franchise.

The Orioles got off to a 3-8 start in ’79 season before reeling off a nine-game winning streak and the first of two stretches in which they won 15 of 16 games. Over the seven weeks, they jockeyed with others for the AL East lead. But on June 6, Dennis Martinez tossed a 3-0 shutout against Kansas City that moved the Orioles into first place. No one knew it at the time, but they would not relinquish the division lead again.

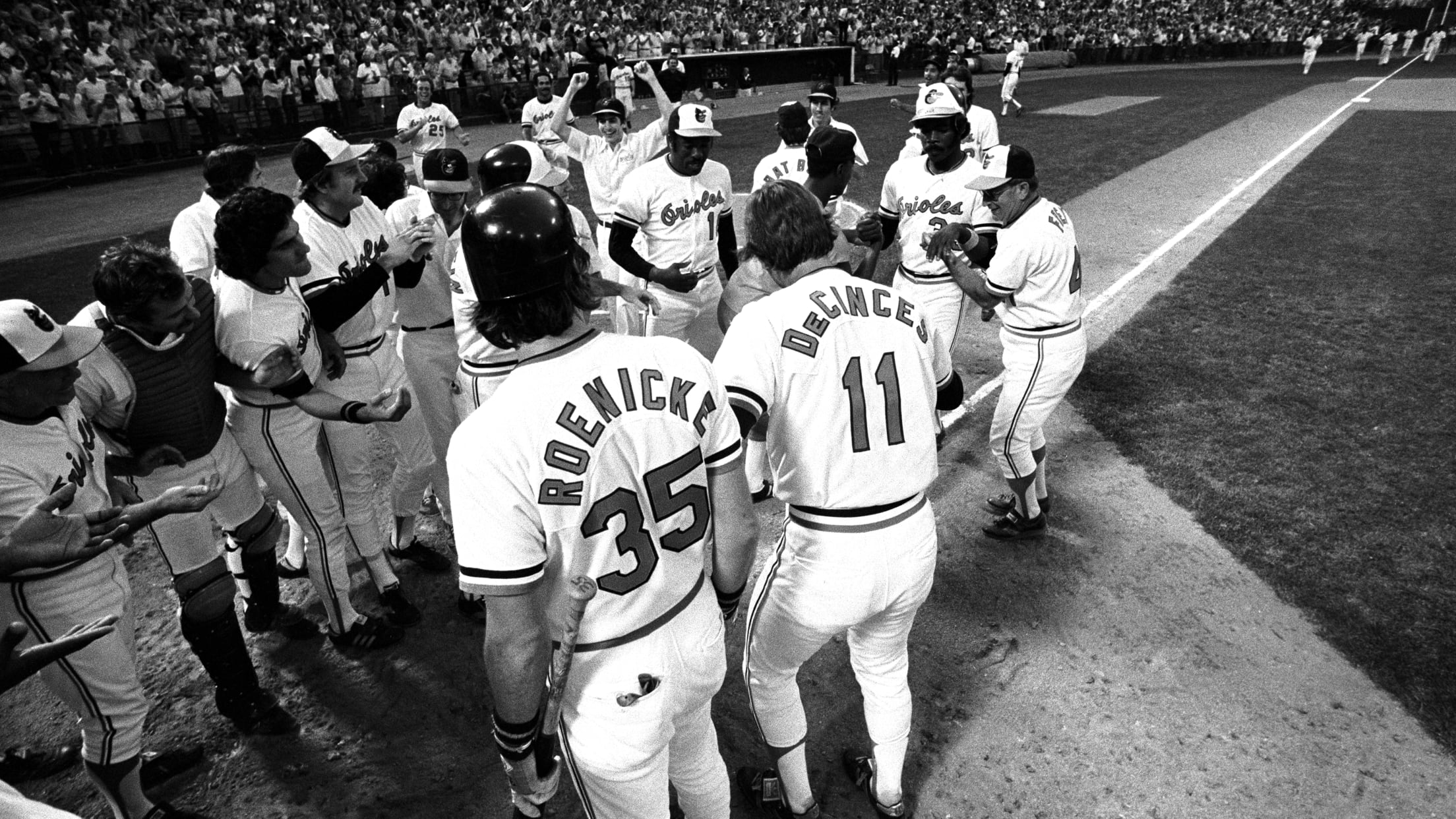

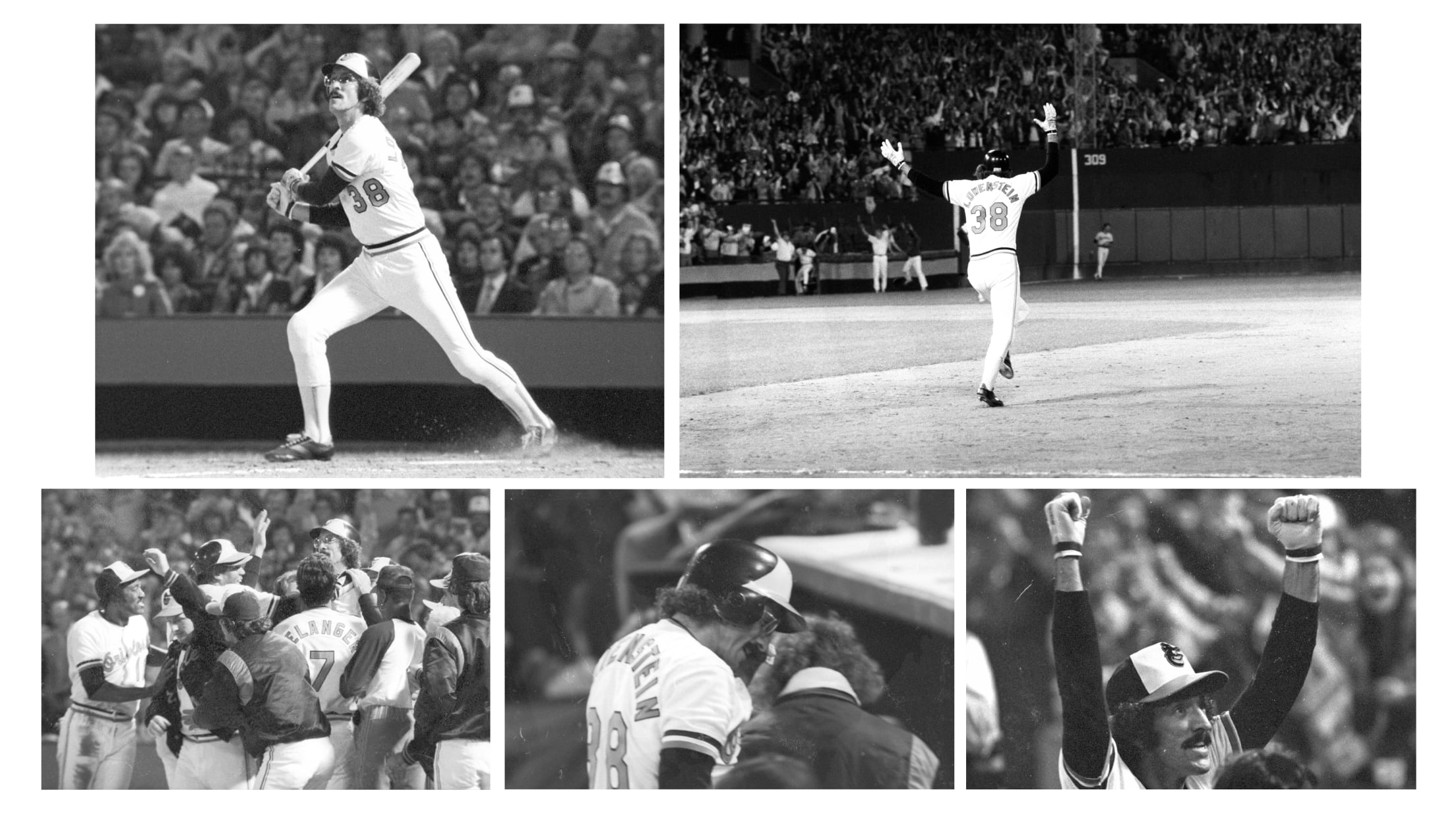

The Orioles held a 3.0-game lead in the AL East standings when they hosted the Detroit Tigers in the first of a four-game series on Friday, June 22 at Memorial Stadium. The Orioles had won six straight and 12 of their previous 13 games, and a loud Friday night crowd of 35,456 was on hand as the Orioles came to bat in the bottom of the 9th, trailing 5-3. Singleton hit a one-out homer to cut the deficit to one run. With two outs and Murray on first following a single, DeCinces stepped to the plate.

What happened next was the dawning of Orioles Magic. With the crowd roaring, DeCinces connected off Tigers reliever Dave Tobik. Fans at home listening to the game on their radio – this was not one of the five home games that were televised that season – heard normally staid announcer Bill O’Donnell’s voice rise as WFBR’s sports director and broadcast booth sidekick, the colorful Charlie Eckman, implored DeCinces’ two-run blast to left field to “GET OUT, GET OUTTA HERE!”

The ball landed in the left field seats, giving the Orioles a 6-5 win. In the stands, in homes, and on back porches across the city, people danced and cheered. Many made plans to come out the next night.

And come out they did, nearly 46,000 of them, for a twi-night doubleheader against the Tigers. In a close case of déjà vu, Murray launched a three-run homer in the bottom of the 9th inning of the first game to give the Orioles their second consecutive sudden-death win, 8-6. The nightcap ended without quite as much drama: the Orioles scored twice to tie the game 5-5 in the 7th inning on Singleton’s two-run single, and Crowley’s pinch-hit single in the 8th plated the game-winning run in a 6-5 victory. The sweep capped another nine-game winning streak and a second run of 15 wins in 16 games.

Despite losing to the Tigers on Sunday, the late-inning comebacks on Friday and Saturday epitomized the Orioles never-say-die attitude on the field, and heightened the good vibrations in the stands at Memorial Stadium. It had all merged serendipitously during and after that single weekend. The reaction around office water coolers across town the following Monday morning was unusually upbeat for the start of a new work week: “Were you at the game? Did you hear the game?” And the O’Donnell cut-ins of the DeCinces and Murray game-winning home run calls made “Orioles Magic” the most played song on Baltimore radio.

“Orioles Magic was the most unbelievable era,” said Dempsey. “Every single night, Lowenstein, Roenicke, DeCinces, Murray, May – somebody stepped up and won the game. It was dominated by the home runs, but whatever we needed, we got it.”

From that point, the Orioles methodically built their lead in the division. They took a two-game lead into the All-Star break and began the second half by winning 15 of 17 games to lead by 8.0 games on August 4. They stretched the lead to 12.5 games with a 7-game winning streak in early September and won the division with ease.

“It was a team that wouldn’t be denied,” Singleton recalled. “Not very much went wrong for us that year.”

In Game One of the AL Championship Series against the (then-California) Angels, the teams were tied 3-3 in the bottom of the 10th inning. With two outs and two on, Weaver called on Lowenstein to pinch-hit for Mark Belanger, and Brother Lo delivered a three-run homer. The Orioles nearly won Game Two, 9-8, but allowed two runs in the 9th to lose Game Three by a 4-3 margin. McGregor removed any doubt however, pitching a six-hit shutout to win to wrap up the best-of-5 series the next day.

For the second time in the decade, the Orioles and Pittsburgh Pirates met in the World Series, and the results were frighteningly similar. Despite taking a 3-games-to-1 lead and having home field advantage, the Orioles dropped the final three games and lost their bid for the world championship.

“It was a very disappointing World Series,” Dempsey recalled. “Momentum is a vicious thing, which we didn’t understand at the time. We learned it that year and it served us well in 1983.”

And so, while it didn’t quite turn out exactly like the Orioles had hoped on the field, the season did usher in a new era of fan support. The local fan support helped break the club attendance record of 1.2 million fans that had been set in 1966, as the ’79 Orioles drew nearly 1.7 million fans for 72 home dates.

A community had awakened to a certain love and unity, and a firm bond with the team was established.

Bumbry, the team’s lead-off hitter and center fielder, when asked recently what his all-time favorite moment as a player was, said, “The thing I remember most is the parade they had for us after the ’79 season. I mean, we lost the World Series, and the fans treated us like we had won. It was just so amazing, so special.”

“Seventy-nine was so special, for the players and the fans,” Dempsey said. “I don’t think we’ll ever see a season like it again.”

This story was originally published in the 2009 Second Edition of Orioles Magazine. Birdland Insider features original content from Orioles Magazine, including new articles and stories from our archives.