History of Black Baseball Part III

In the United States, however, Black people often found themselves in more distasteful roles. To attract crowds throughout the nation and to keep fans interested in the frequently one-sided contests against amateur competition, some Black clubs injected elements of clowning and showmanship into their pregame and competitive performances. As early as the 1880s, comedy had characterized many barnstorming teams. Black baseball, even in its most serious form, tended to be flashier and less formal than white play. Against inferior teams, players often showboated and flaunted their superior skills. Pitcher Satchel Paige would call in his outfielders or guarantee to strike out the first six or nine batters to face him against semi-professional squads. In the late 1930s, Olympic star Jesse Owens traveled with the Monarchs, racing against horses in pregame exhibitions.

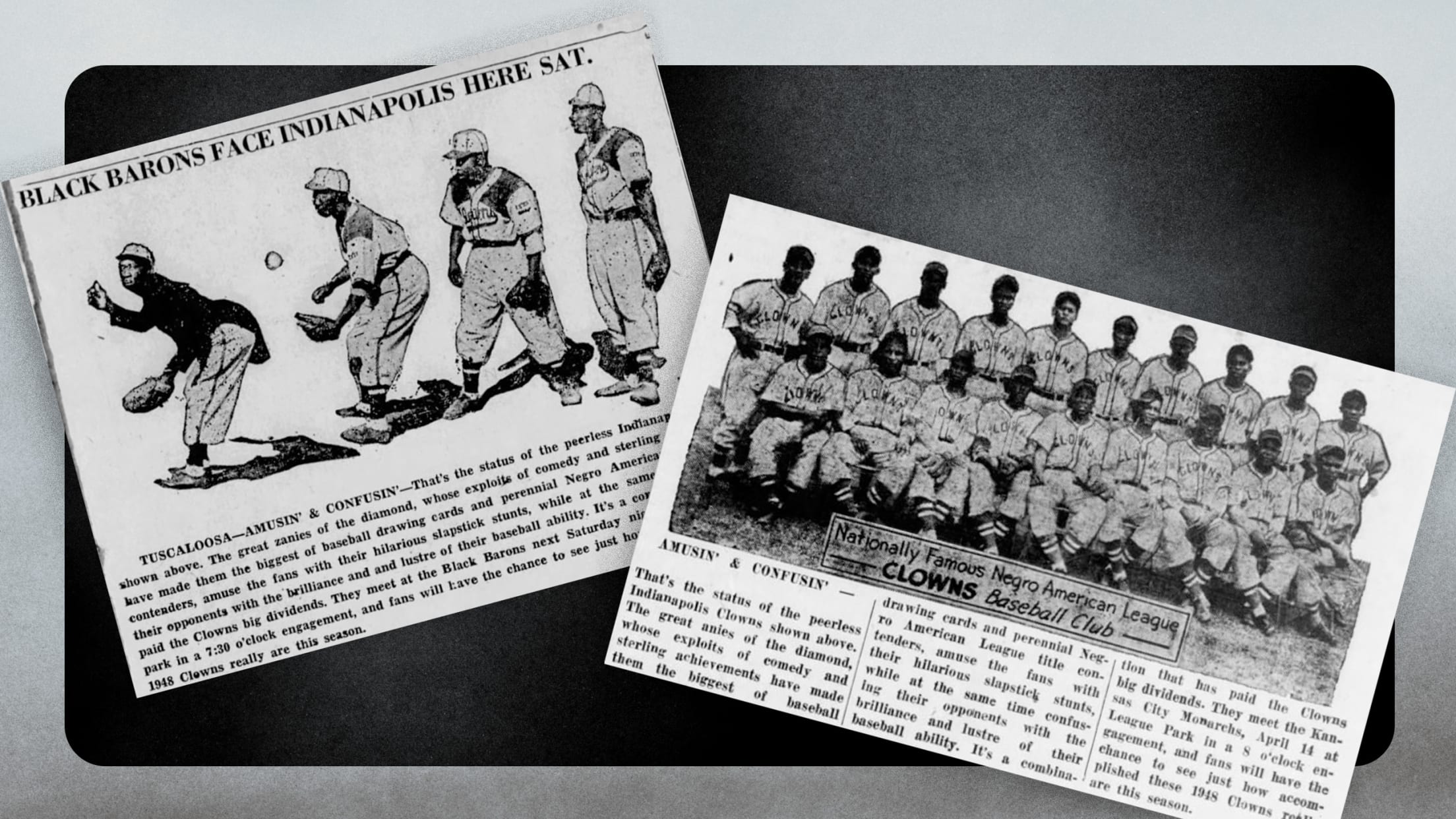

Black teams, like the Tennessee Rats and Zulu Cannibals, thrived on their minstrel show reputations. The most famous of these franchises were the “Ethiopian Clowns.” Originating in Miami in the 1930s, the Clowns later operated out of Cincinnati and then Indianapolis. Their antics included a “pepperball and shadowball” performance (later emulated by basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters), and mid-game vaudeville routines by comics Spec Bebop, a dwarf, and King Tut. Players like Pepper Bassett, “the Rocking Chair Catcher,” and “Goose” Tatum, a talented first baseman and natural comedian, enlivened the festivities. By the 1940s, the Clowns, through the effort of booking agent Syd Pollack, dominated the baseball comedy market. In 1943, their popularity won the Clowns entrance into the Negro Leagues, although other owners demanded they drop the demeaning “Ethiopian” nickname. Although never one of the better Black teams, the Clowns greatly bolstered Negro League attendance.

Their popularity notwithstanding, the comedy teams reflected one of the worst elements of Black baseball. The Clowns and Zulus perpetuated stereotypes drawn from Stepin Fetchit and Tarzan movies. “Negroes must realize the danger in insisting that ballplayers paint their faces and go through minstrel show revues before each ballgame,” protested sportswriter Wendell Smith. Many Black players resented the image that all were clowns. “Didn’t nobody clown in our league but the Indianapolis Clowns,” objected Piper Davis. “We played baseball.”

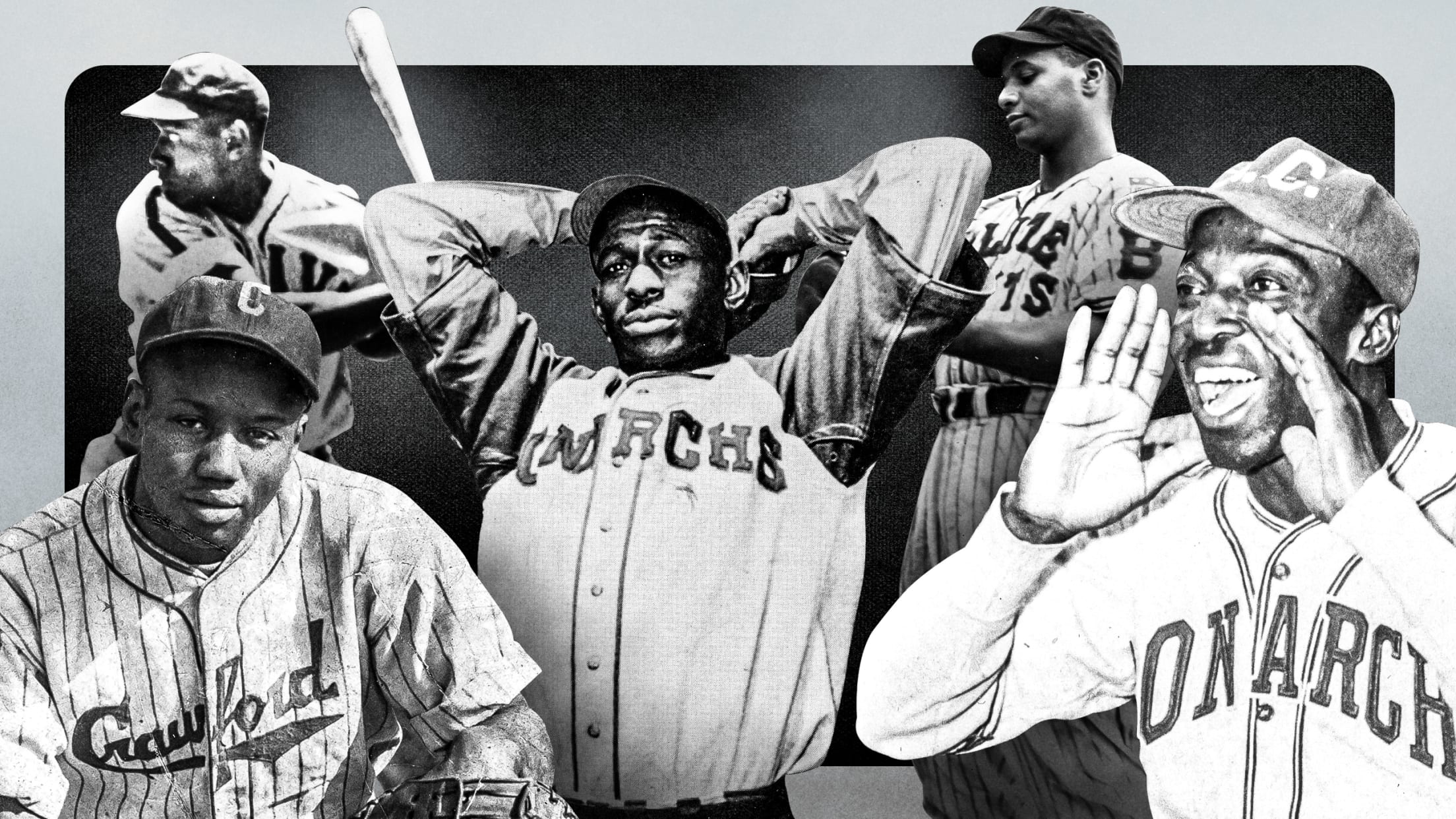

Even without the clowning, Black baseball offered a more freewheeling and, in many respects, more exciting brand of baseball than the Major Leagues. Since the 1920s, when Babe Ruth had revolutionized the game, the Majors had pursued power strategies, emphasizing the home run above all else. Although the great sluggers of the Negro Leagues rivaled those in the National and American Leagues, they comprised but one element in the speed-dominated universe of “tricky baseball.” Black teams emphasized the bunt, the stolen base, and the hit-and-run. “We played by the ‘coonsbury’ rules,” boasted second baseman Newt Allen. “That’s just any way you think you can win, any kind of play you think you could get by on.” In games between white and Black all-star teams, this style of play often confounded the major leaguers.

Centerfielder James “Cool Papa” Bell personified this approach. Bell was so fast, marveled rival third baseman Judy Johnson, “You couldn’t play back in your regular position or you’d never throw him out.” In one game against a Major League All-Star squad, Bell scored from first base on a sacrifice bunt! In center field, his great speed allowed him to lurk in the shallow reaches of the outfield, ranging great distances to make spectacular catches.

Negro League pitching also took on a peculiar caste. “Anything went in the Negro League,” reported catcher Roy Campanella, “Spitballs, shineballs, emery balls; pitchers used any and all of them.” Since league officials could not afford to replace the balls as frequently as in organized ball, scuffed and nicked baseballs remained in the game, giving pitchers great latitude for creative efforts. “I never knew what the ball would do once it left the pitcher’s hand,” recalled Campanella.

Since most rosters included only 14 to 18 men, Negro League players demonstrated a wide range of versatility. Each was required to fill in at a variety of positions. Star pitchers often found themselves in the outfield when not on the mound. Some won renown at more than one position. Ted “Double-Duty” Radcliffe often pitched in the first game of a doubleheader and caught in the second. Cuban Martin Dihigo, whom many rank as the greatest player of all time, excelled at every position. In 1938, in the Mexican League he led the league’s pitchers with an 18–2 record and the league’s hitters with a .387 average.

The manpower shortage offered opportunities for individuals to display their all-around talents, but it also limited the competitiveness of the Black teams. While on a given day a Negro League franchise, featuring one of its top pitchers, might defeat a Major League squad, most teams lacked the depth to compete on a regular basis. “The big leagues were strong in every position,” remarked Radcliffe. “Most of the colored teams had a few stars but they weren’t strong in every position.”

While Black teams may not have matched the top clubs in organized baseball, the individual stars of the 1930s and 1940s clearly ranked among the best of any age. Homestead Gray teammates Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard won renown as the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig of the Negro Leagues. The Grays discovered Gibson in 1929 as an 18-year-old catcher on the sandlots of Pittsburgh, where he had already earned a reputation for 500-foot home runs. For 17 years, he launched prodigious blasts off pitchers in the Negro Leagues, on the barnstorming tour, and in Latin America. As talented as any Major League star, Gibson died in January 1947, at age 35, just three months before Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Leonard, four years older than Gibson, starred in both the Negro and Mexican Leagues as a sure-handed, power-hitting first baseman. The Newark Eagles in the early 1940s boasted the “million dollar infield” of first baseman Mule Suttles, second baseman Dick Seay, shortstop Willie Wells, and third baseman Ray Dandridge. The acrobatic fielding skills of Seay, Wells and Dandridge led Campanella to call this the greatest infield he ever saw.

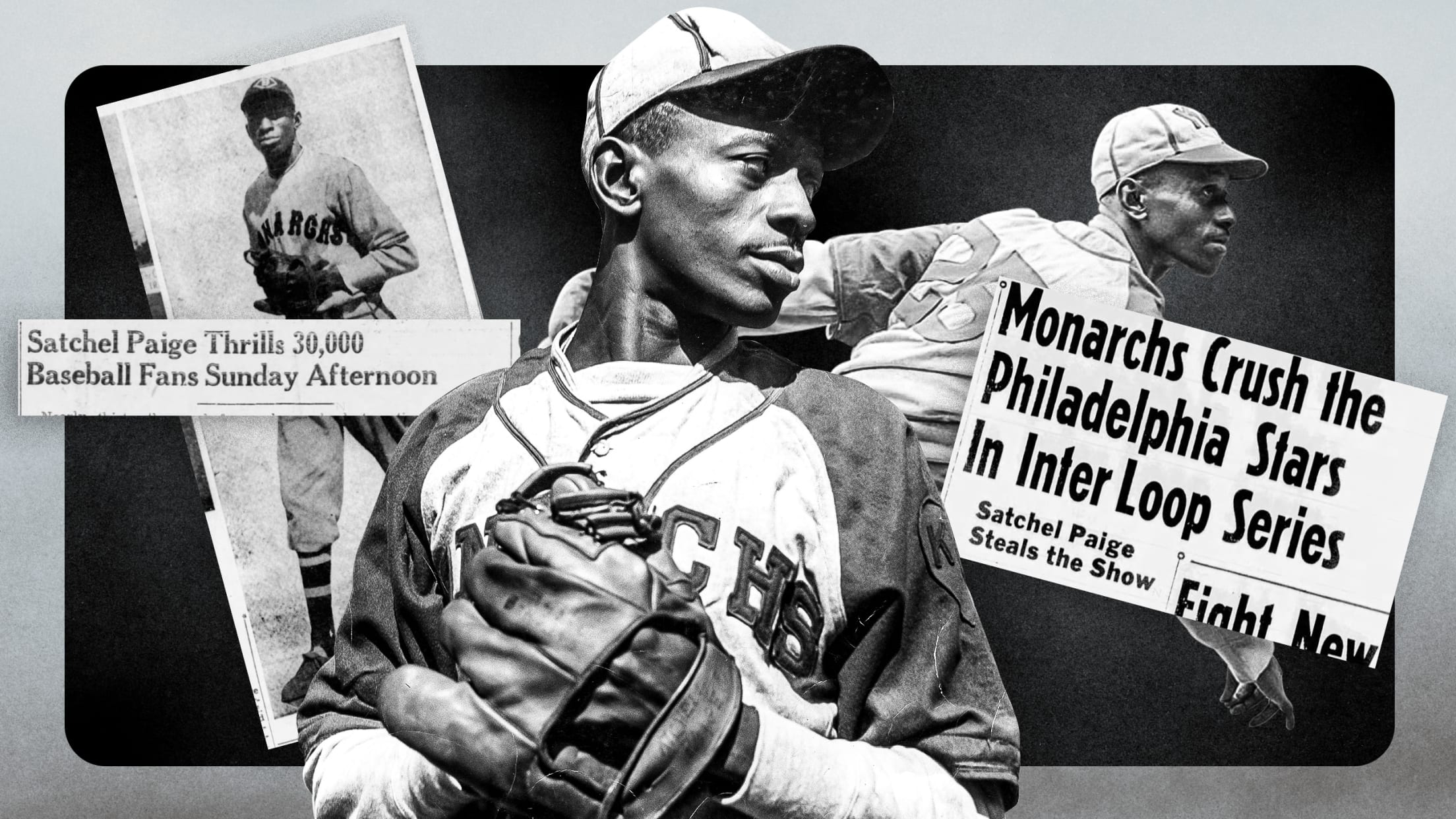

Amidst the many talented Negro Leaguers of 1930s and 1940s, however, one long, lean figure came to personify Black baseball to Black and white fans alike. Leroy “Satchel” Paige began his prolonged athletic odyssey in his hometown in 1924 as a 17-year-old pitcher with the semi-professional Mobile Tigers. He joined the Chattanooga Black Lookouts of the Negro Southern League in 1926. Two years later, the Lookouts sold his contract to the Birmingham Black Barons. By 1930, his explosive fastball, impeccable control, and eccentric mannerisms had made him a legend in the South. In 1932, Gus Greenlee brought Paige to the Pittsburgh Crawfords where the colorful pitcher embellished his reputation by winning 54 games in his first two years. Greenlee also began the practice of hiring out Paige to semi-professional clubs that needed a one-day box office boost.

For seven years Paige feuded with Greenlee, jumping the club when a better offer appeared, being banished “for life,” and then returning. In the mid-1930s, in addition to his stints with the Crawfords, Paige won fame by boosting Bismarck, North Dakota, to the national semi-professional championships, hurling for the Dominican Republic at the behest of dictator Rafael Trujillo, in the Mexican League, and especially on the postseason barnstorming trail pitted against Dizzy Dean’s Major League All-Stars. “That skinny old Satchel Paige with those long arms is my idea of the pitcher with the greatest stuff I ever saw,” claimed the unusually immodest Dean.

Paige’s appeal stemmed as much from his unusual persona as his pitching prowess. A born showman, Paige’s lanky, lackadaisical presence evoked popular racial stereotypes of the age. “As undependable as a pair of second-hand suspenders,” Paige often arrived late or failed to show. His names for his pitches (the “bee ball” which buzzed and all of a sudden; “be there”; the “jump ball”; and the “trouble ball”) and his minstrel show one-liners enhanced the image. But on the mound, Paige invariably rose to the occasion against top competition or challenged inferior opponents by calling in the outfield or promising to strike out the side.

In 1938, a sore arm threatened to curtail Paige’s career but the Kansas City Monarchs, hoping his reputation alone would draw fans, signed him for their traveling second team. On the road, Paige perfected a repertoire of curves and off-speed pitches, including his famous “hesitation” pitch. When his fastball returned in 1939, he became a better pitcher than ever. Promoted to the main Monarch club, Paige pitched the team to four consecutive Negro American League pennants. From 1941–1947, although officially still a Monarch, Paige spent far more time as an independent performer, hired out by Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson to semi-pro and Negro League clubs. “He kept our league going,” recalled Othello Renfroe. “Anytime a team got into trouble, it sent for Satchel to pitch.” Paige also continued to hurl against Major League All-Star teams. In the 1940s, the example of Satchel Paige, whose legend had spread into the white community, offered the most compelling argument for the desegregation of the National Pastime.

Paige’s exploits against white players revealed a fundamental irony about baseball in the Jim Crow Era. While organized baseball rigidly enforced its ban on Black players within the Major and Minor Leagues, opportunities abounded for Black athletes to prove themselves against white competition along the unpoliced boundaries of the National Pastime. During the 1930s, Western promoters sponsored tournaments for the best semi-professional teams in the nation. These squads often featured former and future major leaguers as well as top local talent. In 1934, the Denver Post tourney, “the little World Series of the West,” invited the Kansas City Monarchs to compete for the $7,500 first prize. The Monarchs fought their way into the finals against the House of David team (also owned by J.L. Wilkinson) only to find themselves confronted on the mound by Paige, rented out to pitch this one game. Paige outdueled Monarchs ace Chet Brewer 2–1. Black teams became a fixture in the Post series, emerging victorious for several consecutive years.

In 1935, the National Baseball Congress began an annual tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The competition attracted community squads heartily bankrolled by local business leaders. Neil Churchill, an auto dealer from Bismarck, North Dakota, recruited a half-dozen Black stars, including Paige and Brewer, to represent the town in the Wichita competition. Bismarck naturally swept the series, and thereafter teams that were either integrated or all Black routinely appeared in the National Baseball Congress invitational each year.

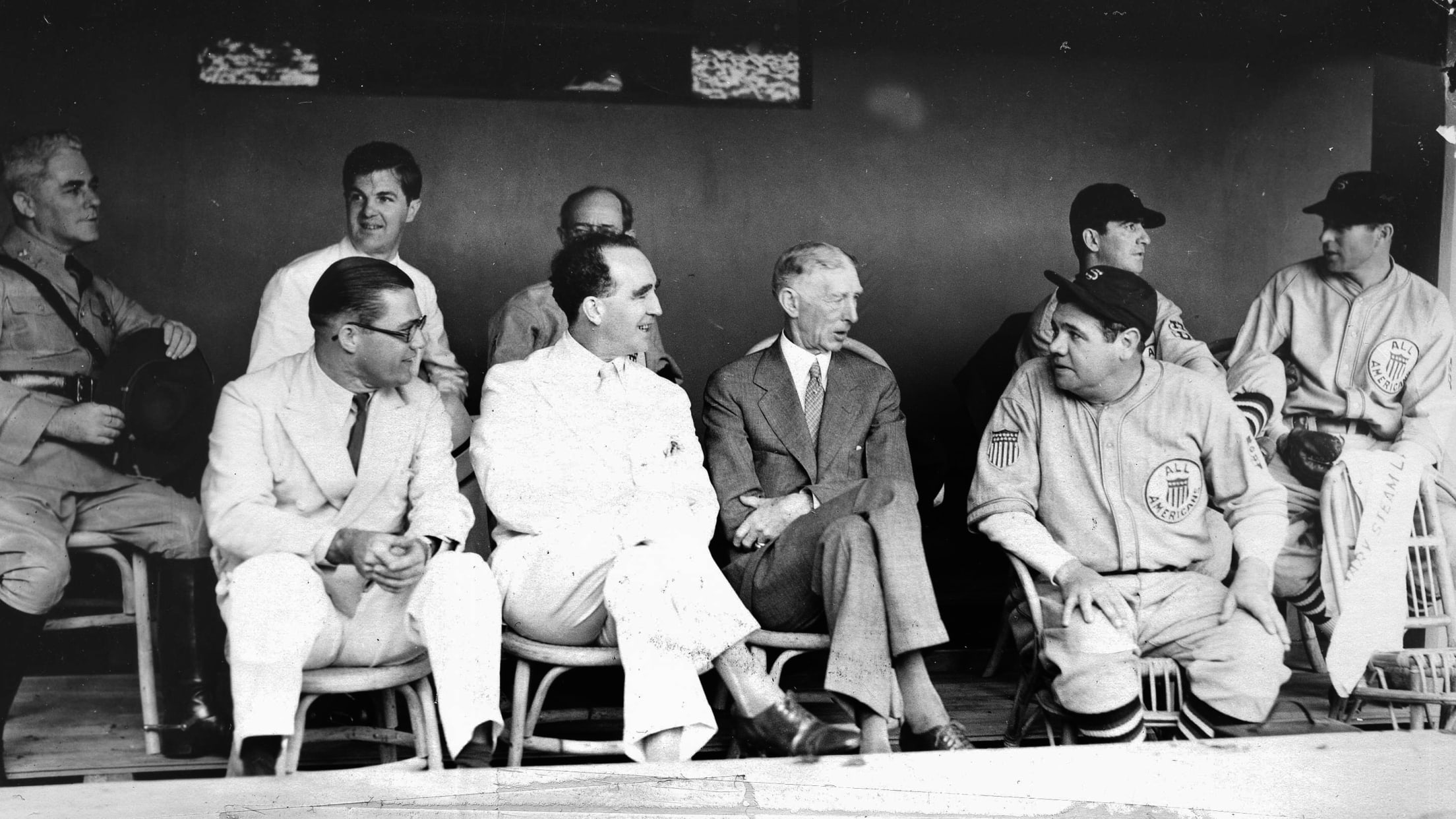

In an age in which the Major Leagues were confined to the East and Midwest, and television had yet to bring baseball into people’s homes, postseason tours by big league stars offered yet another opportunity for Black players to prove their equality on the diamond. Games pitting Black players against white ones were popular features of the barnstorming circuit. Until the late 1920s, when Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis limited postseason play to all-star squads, Black teams frequently met and defeated Major League clubs in postseason competition. During the next decade, matchups between the Babe Ruth or Dizzy Dean “All-Stars” and Black players became frequent. In the autumns of 1934 and 1935, Dean’s team traveled the nation accompanied by the “Satchel Paige All-Stars.” In one memorable 1934 game, called by baseball executive Bill Veeck, “the greatest pitching battle I have ever seen,” Paige bested Dean 1–0.

Surviving records of interracial contests during the 1930s reveal that Blacks won two-thirds of the games. “That’s when we played the hardest,” asserted Judy Johnson, “to let them know, and to let the public know, that we had the same talent they did and probably a little better at times.”

The rivalries proved particularly keen on the West Coast where Monarchs co-owner Tom Baird organized the California Winter League, which included Black teams, white Major and Minor League stars, and some of Mexico’s top players. In 1940, pitcher Chet Brewer formed the Kansas City Royals, which each year fielded one of the best clubs on the coast. One year the Royals defeated the Hollywood Stars, who had won the Pacific Coast League championship, six straight times. In 1945, Brewer’s team, including Jackie Robinson and Satchel Paige, regularly defeated Major League competition.

The most famous of the interracial barnstorming tours occurred in 1946, when Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller organized a Major League All-Star team, rented two Flying Tiger aircraft and hopped the nation accompanied by the Satchel Paige All-Stars. With Feller and Paige each pitching a few innings a day, the tour proved extremely lucrative for promoters and players alike and gave widespread publicity to the skills of the Black athletes.

The World War Two years marked the heyday of the Negro Leagues. With Black and white workers flooding into Northern industrial centers, relatively full employment, and a scarcity of available consumer goods, attendance at all sorts of entertainment events increased dramatically. In 1942, three million fans saw Negro League teams play, while the East-West game in 1943 attracted over 51,000 fans. “Even the white folks was coming out big,” recalled Satchel Paige.

But World War Two also generated forces which would challenge the foundations of Jim Crow baseball. In the armed forces, baseball teams like the Black Bluejackets of the Great Lakes Naval Station team posted outstanding records against teams featuring white major leaguers. In 1945, a well-publicized tournament of teams in the European theater featured top Black players like Leon Day, Joe Green, and Willard Brown in the championship round.

More significantly, the hypocrisy of Black people fighting for their country but unable to participate in the National Pastime grew steadily more apparent. As wartime manpower shortages forced Major League teams to rely on a 15-year-old pitcher, over-the-hill veterans, and one-armed Pete Gray, their refusal to sign Black players seemed increasingly irrational. “How do you think I felt when I saw a one-armed outfielder?” moaned Chet Brewer. Pitcher Nate Moreland protested, “I can play in Mexico, but I have to fight for America where I can’t play.” Pickets at Yankee Stadium carried placards asking, “If we are able to stop bullets, why not balls?”

Amidst this heightened awareness, organized baseball repeatedly walked to the precipice of integration, but always failed to take the final leap. In 1942, Moreland and All-American football star Jackie Robinson requested a tryout at a White Sox training camp in Pasadena, California. Robinson, in particular, impressed White Sox Jimmy Dykes but nothing came of the event. Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher publicly stated his willingness to sign Black players, only to receive a stinging rebuke from Commissioner Landis. Landis again short-circuited integration talk the following year. At the annual baseball meetings, Black leaders led by actor Paul Robeson gained the opportunity to address Major League owners on the issue, but Landis ruled all further discussion out of order.

In 1943, several Minor and Major League teams were rumored close to signing Black players. In California, where winter league play had demonstrated the potential of Black players, several clubs considered integration. The Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League announced tryouts for three Black players, but pressure from other league owners doomed the plan. Oakland owner Vince DeVicenzi ordered manager Johnny Vergez to consider pitcher Chet Brewer, the most popular Black player on the West Coast, for the Oaks. Vergez refused and the issue died. Two years later, Bakersfield, a Cleveland Indians farm team in the California League, offered Brewer a position as player-coach, but the parent club vetoed the plan.

At the Major League level, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith called sluggers Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard into his office and asked if they would like to play in the Major Leagues. They answered affirmatively, but never heard from Griffith again. In Pittsburgh, Daily Worker sports editor Nat Low pressured Pirates owner William Benswanger to arrange a tryout for catcher Roy Campanella and pitcher Dave Barnhill. At the last minute, Benswanger canceled the audition, citing “unnamed pressures.”

For more than two decades, the imperial Landis had reigned over baseball as an implacable foe of integration. While hypocritically denying the existence of any “rule, formal or informal, or any understanding — unwritten, subterranean, or sub-anything — against the signing of Negro players,” Landis had stringently policed the color line. His death in 1944 removed a major barrier for integration advocates.

In April 1945, with World War Two entering its final months, the integration crusade gained momentum. On April 6, People’s Voice sportswriter Joe Bostic appeared at the Brooklyn Dodger training camp at Bear Mountain, New York, with two Negro League players, Terris McDuffie and Dave “Showboat” Thomas, and demanded a tryout. An outraged but outmaneuvered Dodger President Branch Rickey allowed the pair to work out with the club. One week later, a more serious confrontation occurred in Boston. The Red Sox, under pressure from popular columnist Dave Egan and city councilman Isidore Muchnick, agreed to audition Sam Jethroe, the Negro League’s leading hitter in 1944, second baseman Marvin Williams, and Kansas City Monarch shortstop Jackie Robinson, all top prospects in their mid-twenties. The Fenway Park tryout, however, proved little more than a formality and the players never again heard from the Red Sox.

The publicity surrounding these events, however, forced the major leagues to address the issue at its April meetings. At the urging of black sportswriter Sam Lacy, Leslie O’Connor, Landis’ interim successor, established a Major League Committee on Baseball Integration in April 1945, to review the problem. In addition, the racial views of newly appointed Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler came under close scrutiny. A former governor of the segregated state of Kentucky, Chandler nonetheless offered at least verbal support to the entry of blacks into organized ball. “If a Black boy can make it on Okinawa and Guadalcanal, hell, he can make it in baseball,” Chandler told black reporter Rick Roberts. Whether Chandler, however, unlike Landis, would reinforce his rhetoric with positive actions remained uncertain. Unbeknownst to the integration advocates, baseball officials, and local politicians sand-dancing around the race issue, Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, had already set in motion the events which would lead to the historic breakthrough.

Continue to Part IV here.